Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Jing Lin and Version 2 by Dean Liu.

Carbon dioxide (CO2) electroreduction offers an attractive pathway for converting CO2 to valuable fuels and chemicals. Despite the existence of some excellent electrocatalysts with superior selectivity for specific products, these reactions are conducted at low current densities ranging from several mA cm−2 to tens of mA cm−2, which are far from commercially desirable values. To extend the applications of CO2 electroreduction technology to an industrial scale, long-term operations under high current densities (over 200 mA cm−2) are desirable.

- CO2 electroreduction

- electrolyzers

- high current densities

- electrolytes

- long-term operations

- challenges and perspectives

1. Introduction

Electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide (CO2) to chemicals is considered to be a sustainable strategy in preventing our planet from global warming while keeping the growth of our economy. So far, commercially available CO2 electroreduction reaction (CO2ER) technologies are almost nonexistent [1]. A cost-competitive CO2 electrolysis requires a high current density (>200 mA·cm−2), a high selectivity, a low overpotential (<1 V), and a long-term operation (>8000 h or 1 year) [2][3][2,3]. Among these factors, the current density is a key indicator for evaluating the catalytic performance, because a higher current density represents a higher reaction rate. Therefore, technical developments regarding electrocatalyst, electrolyzer, electrolyte, and operational condition are greatly demanded in order to realize high current density.

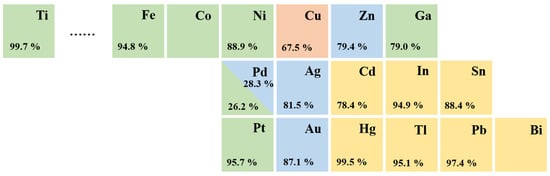

CO2 electroreduction involves different numbers of electrons and protons to produce specific products. Elemental metallic catalysts can be classified into the following three categories according to their major products: (1) Au, Ag, Pd, and Zn to produce CO [4][5][6][4,5,6]; (2) Pb, Bi, Sn, In, and Hg to produce formic acid/formate [7][8][9][7,8,9]; (3) Cu to produce various hydrocarbons [10][11][12][10,11,12]. Although the above catalysts have demonstrated remarkable selectivity towards different products, they are still far away from industrial application, especially regarding the aspect of the current density. However, in order to have a sustainable impact on the environment and climate, industrially relevant research is urgently required [13].

Therefore, the integration of catalyst innovations and reactor designs is desirable. Traditional CO2ERs are conducted in an H-type cell, which is limited to relatively low current densities due to the limited solubility of CO2 in aqueous solution. To meet the requirements for industrialization, various reactor configurations such as the GDE-based flow cell, microchannel reactor, membrane electrode assembly, and high-pressure cell have been developed. Although perovskite catalysts in solid oxide electrolyzer cells (SOECs) can electrolyze CO2 at the gas–solid interface with a high current density [14][15][16][14,15,16], they are not discussed within the scope of this article, due to their restricted operational conditions and products. In an economically practicable electrolyzer, variables related to electrodes, electrolytes, and operations should also be taken into account.

2. Mechanisms of CO2ER

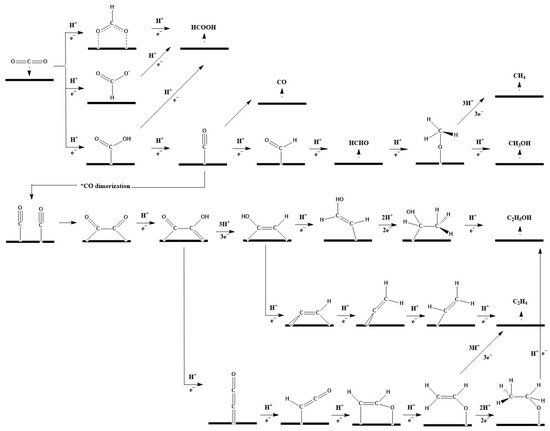

CO2 electrochemical reduction can proceed through reduction pathways involving two to eighteen electrons to produce various products including formic acid (HCOOH)/formate (HCOO−), carbon monoxide (CO), methane (CH4), methanol (CH3OH), acetic acid (CH3COOH), ethanal (CH3CHO), ethanol (CH3CH2OH), ethylene (CH2CH2), and others. The most commonly reported reactions are listed below in Table 1.Table 1.

Electrochemical reactions and their equilibrium potentials.

| Reaction | E0/(V vs. RHE) |

|---|---|

| 2H+ + 2e− → H2 | 0.00 |

| CO2 + 2H++ 2e− → CO + H2O | −0.10 |

| CO2 + 2H+ + 2e− → HCOOH | −0.12 |

| CO2 + 6H+ + 6e− → CH3OH + H2O | +0.03 |

| CO2 + 8H+ + 8e− → CH4 + 2H2O | +0.17 |

| 2CO2 + 8H+ + 8e− → CH3COOH + 2H2O | +0.11 |

| 2CO2 + 10H+ + 10e− → CH3CHO + 3H2O | +0.06 |

| 2CO2 + 12H+ + 12e− → CH3CH2OH + 3H2O | +0.09 |

| 2CO2 + 12H+ + 12e− → C2H4 + 4H2O | +0.08 |

| 3CO2 + 18H+ + 18e− → CH3CH2CH2OH + 5H2O | +0.10 |

Figure 1.

Proposed reaction routes for CO

2

electroreduction to various products such as CO, HCOOH, CH

4

, CH

3

OH, C

2

H

4

, and C

2

H

3. Electrocatalysts for CO2 Electroreduction

Elemental metallic catalysts for CO2 electroreduction are traditionally classified into four distinct groups depending on their major products, according to experimental data produced by Hori et al. [29] (Figure 2). In aqueous electrolytes, Au, Ag, and Zn catalysts mainly produce CO, whereas Cd, In, Sn, Hg, Tl, Pb, and Bi [30] catalysts favor the production of HCOOH. Cu is unique, and only Cu-based catalysts are able to yield large amounts of hydrocarbons, as they facilitate the formation of C-C bonds [31][32][31,32].

Figure 2. Periodic table and Faradaic efficiencies of various metals depending on the major products in CO2 electroreduction: CO (blue); HCOOH (yellow); mixed hydrocarbons (red); H2 (green).

4. Conclusions and Outlook

ReThisearchers paper systematically summarized the major research conducted at relatively high current densities in order to meet the requirements of industrial applications of CO2ER. Explorations of metal catalysts, especially the innovations of novel nanostructures and composite materials, are major fields for researchers to develop. In addition, the optimal design of reactors and the arrangement of the reaction microenvironment are also being investigated to improve the activity. Despite remarkable advances having been made in various aspects, long-term experiments at high current densities (>1 A cm−2) have not yet been carried out stably. On Researchersthe basis of recent progress, we would like to emphasize four directions for future development:

- (1)

-

The design of cost-efficient catalysts. Novel and cheap catalysts should be developed to replace or reduce the use of noble metals. Tailoring the morphology, crystal structure, and electronic distributions are three important strategies to optimize the usage of the active sites. By introducing heteroatoms (e.g., N, P, or other chalcogens), other metals, or specific functional groups, the lattice defects of metal catalysts such as vacancies and grain boundaries can be regulated.

- (2)

-

Innovations in electrolyzers. Progress is also needed in the design of cheaper electrolyzers with higher efficiency. The facility should also be flexible enough to adapt to different CO2 resources such as CO2 captured from flue gas and biogas. At the same time, the use of a GDE (e.g., carbon matrix, PTFE) for stable and large-scale CO2 conversion should be optimized. In the future, better GDEs with excellent conductivity, hydrophobicity, and appropriate ventilation will be an intriguing development direction.

- (3)

-

Research into non-OER anode reactions. Although the anodic OER reaction is green, it does not yield economic benefits. Coupling CO2ER with an anode oxidation reaction with more commercial value could be another industrially accessible approach. In this manner, CO2 electrolyzers could be easily integrated into other industrial processes in which the main product is formed on the anode. The existing challenge is proper product separation.

- (4)

-

The exploration of complicated mechanisms. The electroreduction of CO2, especially to C2+ products, involves various electron transfer processes and the formation of intermediates. Theoretical calculations can provide new insights into the structure–property relationship and the rational design of catalysts. Remarkable effort has been dedicated to obtaining a better mechanistic understanding through DFT calculations and operando/in situ techniques. However, computational models are simplified and limited at present and require further development.