Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Beatrix Zheng and Version 1 by Minho Moon.

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease accompanied by cognitive and behavioral symptoms. These AD-related manifestations result from the alteration of neural circuitry by aggregated forms of amyloid-β (Aβ) and hyperphosphorylated tau, which are neurotoxic. From a neuroscience perspective, identifying neural circuits that integrate various inputs and outputs to determine behaviors can provide insight into the principles of behavior. Therefore, it is crucial to understand the alterations in the neural circuits associated with AD-related behavioral and psychological symptoms. Interestingly, it is well known that the alteration of neural circuitry is prominent in the brains of patients with AD.

- Alzheimer’s disease

- neural pathways

- neural circuits

- neurodegeneration

- connectome

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common type of dementia in the elderly and is a significant health problem worldwide. The incidence of AD increases with age, with nearly 35% of 85-year-olds suffering from AD [1,2][1][2]. AD has been characterized by the aggregation and accumulation of amyloid-β (Aβ) and hyperphosphorylated tau. In addition, AD is a progressive neurodegenerative disease in which cognitive impairment is the main symptom [3]. Moreover, the secondary symptoms are as follows: psychiatric, sensory, and motor dysfunctions [4,5][4][5]. Therefore, AD treatment should inhibit cognitive decline and induce various clinical symptoms [6]. Based on many theories and hypotheses, many clinical trials are underway to treat AD. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has recently approved an Aβ-binding monoclonal antibody, aducanumab (Aduhelm), through an accelerated approval pathway [7]. Although aducanumab may be beneficial in reducing in amyloid plaques in the brains of AD patients, it is not associated with behavioral improvement. Therefore, definitive treatment for cognitive and behavioral deficits is required.

Neural circuits are the main mediators of various behaviors controlled by the brain, from simple functions to complex cognitive processes [8]. Interestingly, it is known that Aβ and tau have been progressively impaired the synapses, neuronal circuits, and neural networks in the brain with AD [9,10][9][10]. Several studies using neural tracing and radiological imaging, such as diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) have shown that neural pathways are altered in AD brains [11,12,13][11][12][13]. Damage to neural circuits in the AD brain can result in cognitive impairment, such as memory deterioration [14]. In addition, it has been suggested that the alterations in neural circuits and network function due to pathological changes in synaptic plasticity might be associated with several clinical symptoms, such as sensory and motor dysfunctions [4]. Interestingly, clinical studies have shown changes in the sensory systems of patients with early-stage AD, and that these changes take precedence over cognitive impairment [15,16,17][15][16][17]. From this perspective, neural circuitry could be a target for treating various symptoms of AD. Therefore, wthe researchers selected the brain regions involved in changes in cognition and several clinical manifestations of AD, and summarized the alteration of efferent pathways from these AD-associated brain regions.

The challenge for neuroscience is to visualize the essential structural elements of the brain from the perspective of neural connections related to behaviors [12,18][12][18]. For the visualization of the neural connectivity or network related to behavior, there are three levels of brain connectivity: macroscale, mesoscale, microscale [19]. The macroscale connectome anatomically represents inter-area connections between distinct brain regions and shows the most large-scale connection patterns in the brain. In particular, DTI and fMRI are widely used to infer structural and functional connections in the living brain [20]. The microscale connectome represents the level of pre-and post-synaptic connections between single neurons. Microscale studies use electron and light microscopy to demonstrate neural connections at the ultrastructural level [21]. The mesoscale connectome represents intercellular connections between different neurons across different brain regions. In addition, mesoscale connectivity provides a detailed understanding of the cell-type composition of different brain regions, and the patterns of inputs and outputs that each cell type receives and forms, respectively [22]. Therefore, the mesoscale connectome can connect information collected at the level of both macroscale and microscale connectivity. In addition, at the mesoscale level, both long-range and local connections can be described using a sampling approach with diverse neuroanatomical tracers that enable whole-brain mapping in a reasonable time frame across many animals [23].

To understand AD-related cognitive, behavioral, and psychological symptoms, a precise connection of neural circuits should be examined. Moreover, understanding the alterations of neural circuits in the brain with AD might provide a better understanding of possible treatments that substantially affect the progression of AD.

2. Targeting the Neural Circuits for Treatment of AD

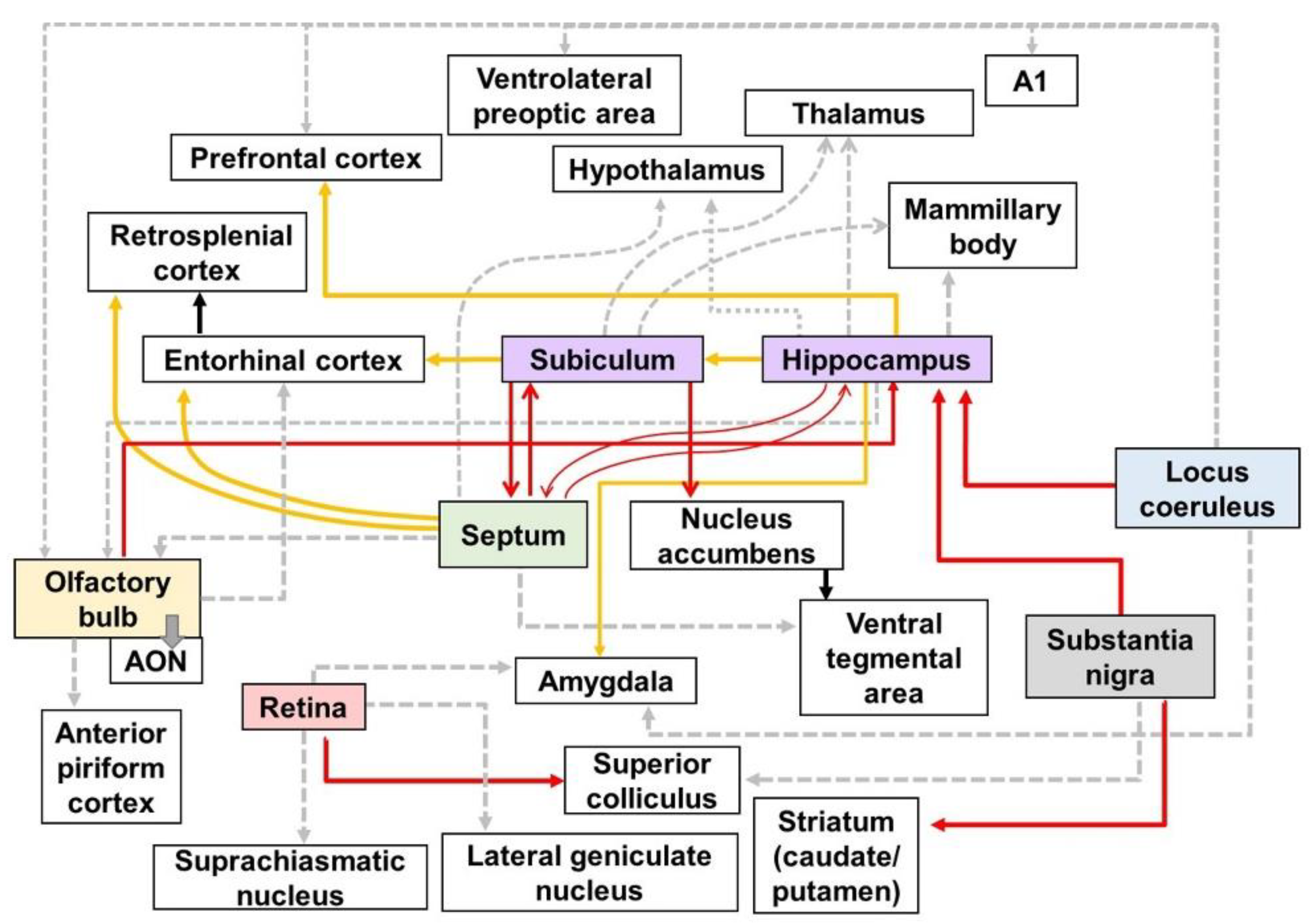

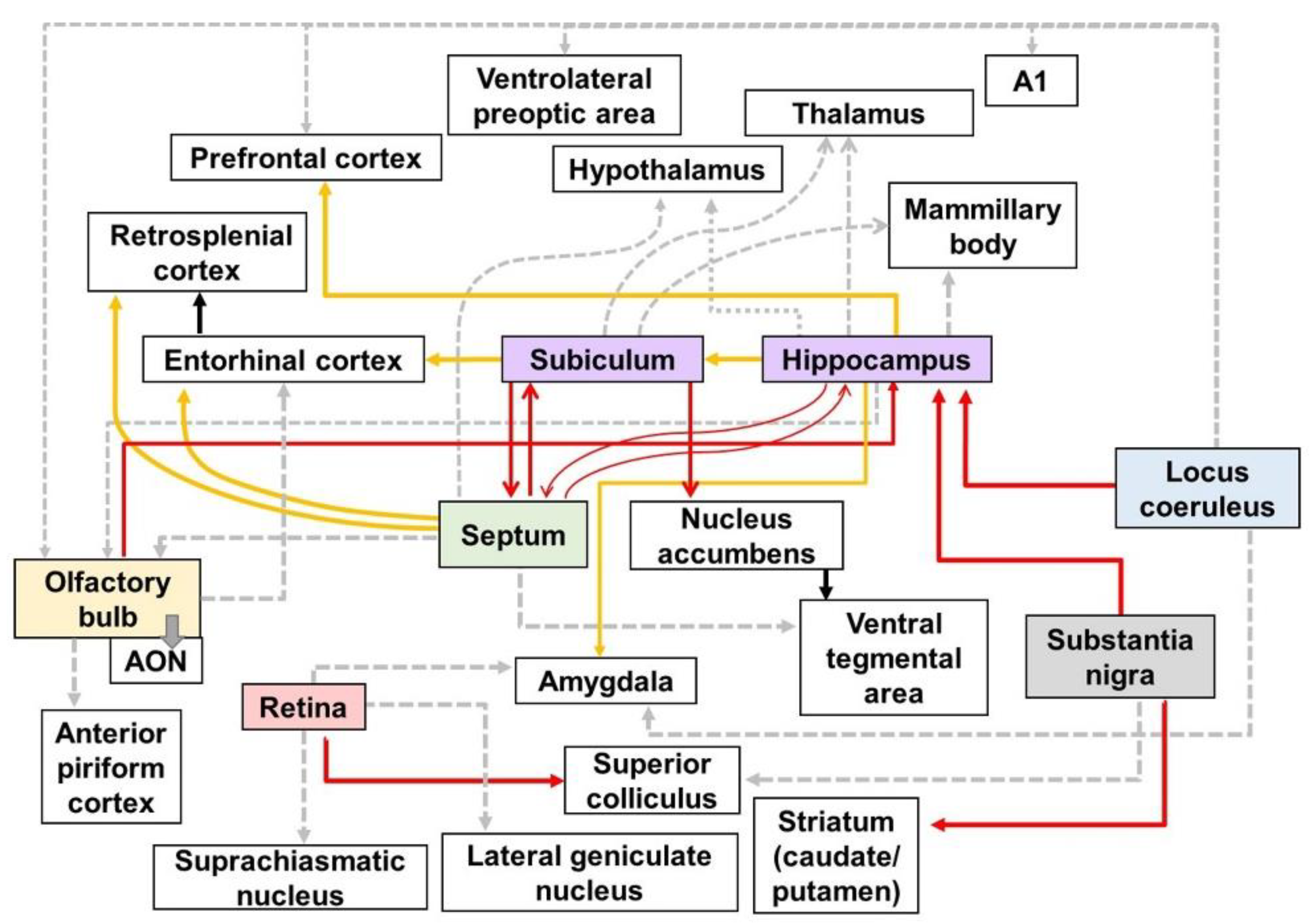

In this revisew, wearch, the researchers identified impairments in the neural circuits of the AD brain (Figure 7Figure 1). The degeneration of neural circuits is a trigger for the several clinical symptoms of AD. In particular, it is known that cognitive decline in AD is caused by the impairment of neural pathways [14,229][14][24]. Although the specific relationship between altered neural circuits and behavioral deficits in AD is not yet fully understood, it is likely that various AD-related neuropsychiatric symptoms have also been associated with neural circuit impairment [230][25]. Several studies have suggested that a therapeutic approach to restoring the neural circuit may be effective in improving the clinical symptoms of patients with AD [10,231][10][26]. In addition, as clinical trials targeting molecular pathologies such as Aβ and tau pathology have failed one after the other, their potential as therapeutic targets of neural circuits is increasing [9,231][9][26]. Therefore, it has been strongly suggested that the recovery of impaired neural circuits can be an effective therapeutic target for the treatment of AD symptoms, including cognitive and psychiatric deficits. Based on the accumulated evidence, wthe researchers discuss the potential of neural circuits as therapeutic targets, as well as promising therapeutic approaches for neural circuits in AD treatment.

For therapeutic strategies targeting neural circuits, it is important to choose the right patient and time. The natural course of AD is as follows: preclinical, prodromal, mild, moderate, and severe AD. In addition, AD patients are categorized based on imaging and biofluid biomarkers using the ATN (A: Aβ, T: tau, N: neurodegeneration) classification system [232][27]. Following the framework provided by ATN classifications, the right time and patient for AD treatment targeting neural circuits would be prodromal to mild AD patients with cellular dysfunction [233][28]. Moreover, deficits in several neural circuits in AD occur in the early stages [13]. Strategies to restore damaged neural circuits are expected to have a high probability of success in patients with MCI. Furthermore, the combination of protecting or stimulating neural connections by targeting Aβ and tau is thought to be the optimal strategy to alleviate both the pathology and symptoms of AD. Collectively, this strategy of targeting neural circuits can be applied as a combination therapy in the early stage of AD, and can help alleviate symptoms by activating the remaining circuit in the late stage of AD.

Several potential therapeutic approaches have been proposed for the restoration of neural circuits. Optogenetics, which uses light to modulate neural circuits, is emerging as a novel approach for the treatment of CNS diseases [234][29]. Optogenetics has been proposed as an accurate treatment that can specifically modulate only certain types of neurons [235][30]. Surprisingly, the modulation of the glutamatergic pathway through optogenetic therapy in the medial PFC of rodents increased recognition memory [236][31]. In addition, optogenetic therapy has been shown to have a significant therapeutic effect in an AD transgenic model [235][30]. In Tg2567 mice, optogenetic stimulation ameliorated the decline in spatial learning and memory function by protecting the connectivity of the entorhinal–hippocampal CA1 pathway [235][30]. Moreover, spatial memory was improved in J20 mice via optogenetic modulation for gamma oscillations of the MS pathway [237][32]. Moreover, chemogenetics, which uses designer receptors exclusively activated by designer drugs (DREADDs), has also been suggested to be an effective method to modulate neural activity and correct neural circuit dysfunction [238][33]. Chemogenetic therapy alleviated AD pathology in 5XFAD mice and improved performance in behavioral tests by modulating the abnormal activity of neuronal pathways in TgF344-AD rats [239,240][34][35]. Therefore, viral-mediated gene therapy, including optogenetics and chemogenetics for damaged neural circuits, may be a promising treatment for AD.

Another possible approach to modulating neural circuitry to treat AD-related symptoms is through transcranial electrical stimulation (tES). tES is a non-invasive treatment that electrically stimulates the brain through the scalp and includes transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), as well as transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) [241][36]. TMS stimulates the brain using an intensive magnetic field [242][37]. In several studies, repetitive TMS restored cognitive dysfunction in patients with MCI and with mild or moderate AD [243][38]. Another study also suggested that TMS intervention in AD patients may contribute to the recovery of memory loss and cognitive dysfunction in the brain with AD [244][39]. One of the suggested potential mechanisms of TMS is the regulation of vulnerable circuit connectivity [243,244][38][39]. Based on these studies, a randomized clinical trial to verify the effectiveness of TMS in patients with AD is ongoing (NCT03121066). Furthermore, tDCS improved motor and cognitive functions, including recognition memory, in MCI and AD patients [245][40]. Moreover, tDCS has been suggested to enhance cognitive function in a double-blind placebo control trial in patients with mild and moderate AD [246][41].

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is a surgical treatment that modulates the activation of neural circuits through a neurostimulator device placed in the brain [247][42]. The therapeutic effect of DBS is well known in neurodegenerative diseases [248][43]. In addition, accumulating evidence suggests that DBS may be an effective method for improving AD [249][44]. DBS for targeting the medial septum in a rat model of dementia restored spatial memory by modulating the septo-hippocampal cholinergic pathway [250][45]. Moreover, DBS for targeting the fornix and hypothalamus in AD patients induced the activation of memory circuits and alleviated cognitive decline [251][46]. Several clinical trials are underway to investigate the effectiveness of DBS in patients with MCI and AD. In addition, gamma entrainment using sensory stimuli (GENUS) improved cognitive function by mitigating AD pathology and restoring the function of neural circuits in AD mouse models [252][47]. In summary, there are possible therapeutic approaches that can be used to modulate neural circuits and restore damaged neural circuits in AD brains, and these therapies can be effective in improving cognitive dysfunction. However, there are still some critical questions to be considered for the effective clinical application of neural-circuit-targeted treatment of AD. Although therapeutic strategies targeting neural circuits have successfully restored the function of altered neural circuits in AD, the long-term effects of these treatments are still unknown. Moreover, the continuously increasing neuronal loss as AD progresses can reduce the effectiveness of the neural-circuit-centered approach. Thus, it is promising to discover strategies that can have neuroprotective effects in the AD brain by targeting neurodegeneration, including neuronal death, synaptic loss, and neural circuit degeneration.

3. Current Insights

This entreviewy provided a summary of altered neural pathways at the mesoscale level (Table 1) and other levels in AD brains (Figure 7Figure 1). The alteration of neural pathways, leading to cognitive decline and behavioral impairment, is an important pathology directly related to AD symptoms. Thus, the weresearchers emphasize the importance of neural pathways for understanding the pathological processes and clinical symptoms of AD. Furthermore, wethe researchers discussed the therapeutic implications of approaches to targeting the neural circuits in AD. Several studies and clinical trials have suggested that therapeutic methods to enhance the activity and connectivity of neural circuits are effective in ameliorating AD pathogenesis. Taken together, wethe researchers conclude that strategies targeting altered neural pathways in the AD brain are potent therapeutic targets for the treatment of AD. Thus, more research is needed, to examine the alterations of the neural pathways in the brain with AD and develop the therapeutic approaches that restore or protect neural connectivity in the AD brain.

Table 1.

Sub—subiculum; DG—dentate gyrus; DTT—diffusion tensor tractography; DTI—diffusion tensor imaging; GABA—gamma-aminobutyric acid; LC—locus coeruleus; MS—medial septum; NAc—nucleus accumbens; OB—olfactory bulb; RSg—granular division of retrosplenial cortex; SN—substantia nigra. The right arrow indicates the direction of projection, and the down arrow indicates decreased connectivity.

Degeneration of the efferent pathways in the brains of AD mouse models.

| Regions | Models | Neural Tracers | Findings | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hippocampal formation | Tg2576 mouse | Fast Blue | Subiculum → NAc ↓ | Decreased glutamatergic transmission from the subiculum to the NAc core. | [51] | [48] |

| 5XFAD mice | DiI | Hippocampal formation → MS ↓ | The DG→MS and Sub→MS pathways was degenerated before cognitive decline. | [40] | [49] | |

| Septal area | Tg601 mice | DTIDTT | MS → hippocampus ↓ | The connectivity of the septo-hippocampal pathway in the old (16- to 18-month-old) mice was reduced compared to healthy and adult (six- to eight-month-old) mice. | [67] | [50] |

| THY-Tau22 mice | FG | MS → hippocampus ↓ | Innervation from the MS to the hippocampus decreased in the 5XFAD mice compared to WT mice. | [68] | [51] | |

| J20 mice | BDA | MS → hippocampus ↓ | GABAergic septo-hippocampal connection was reduced in eight-month-old J20 mice compared to WT mice. | [69] | [52] | |

| VLW mice | BDA | MS → hippocampus ↓ | The GABAergic septo-hippocampal innervation on parvalbumin-positive interneurons deteriorated in two-month-old VLW mice compared to WT mice. | [70] | [53] | |

| 5XFAD mice | DiI | MS → hippocampus ↓ | Innervation from the MS to the hippocampus decreased by about 52% in the 5XFAD mice compared to WT mice. | [12] | ||

| 5XFAD mice | BDA | MS → hippocampal formation ↓ | Impairment of the connectivity of the septo-hippocampal pathway occurred before cognitive decline. | [40] | [49] | |

| Locus coeruleus | 5XFAD mice | DiI | LC → hippocampus ↓ | Innervation from the LC to the hippocampus decreased by about 69.1% in the 5XFAD mice compared to WT mice. | [12] | |

| Substantia nigra | 5XFAD mice | DiI | SN → hippocampus ↓ | Innervation from the SN to the hippocampus decreased by about 41.3% in the 5XFAD mice compared to WT mice. | [12] | |

| Visual area | 3xTg mice | Cholera toxin beta subunit | Retina → superior colliculus ↓ | The retino-collicular pathway through which RGCs reach the terminals in the superior colliculus, which is the primary target of RGCs, is impaired in three-month-old 3xTg mice. | [71] | [54] |

| Olfactory area | 5XFAD mice | DiI | OB → hippocampus ↓ | Innervation from the OB to the hippocampus decreased by about 52% in the 5XFAD mice compared to WT mice. | [12] | |

Figure 71. Schematic diagram of altered connections in the AD brain: Red, yellow, and gray lines directed away from the boxes represent efferent fibers which have synaptic contact with each other. The red lines show the altered efferent pathways in AD brain using the neural tracers identified in Table 1. The yellow lines indicate the output pathways that were investigated using various methods, such as electrophysiology, biomedical imaging technologies, and immunohistochemical stanning. The gray dotted lines represent the efferent pathways that affect various symptoms of AD, although the alteration in the connectivity of gray dotted lines has not been directly visualized. A1—primary auditory cortex; AON—anterior olfactory nucleus.