You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Beatrix Zheng and Version 1 by Khaoula Stiti.

Participation has been an important topic in research across different disciplines, including cultural heritage. The panoply of definitions of participation, whether specific to a discipline or not, makes uspeople acknowledge controversy over the term “participation”. Since 2005, the relevance of participation in cultural heritage has been institutionalized through The Council of Europe Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society, better known as the Faro Convention. It emphasizes that the significance of cultural heritage lies less in the material aspect than in the meanings and uses people attach to them and the values they represent.

- participation

- state of art

- cultural heritage

- actors of participation

- challenges of participation

- democracy

1. Introduction

The Faro Convention puts the people at the heart of the processes of identification, management, and sustainable use of heritage. This can have clear potential benefits [1], such as creating synergies of competencies among all the actors concerned to create democratic societies. It defends a broader vision of heritage and its relationship with communities and societies. Therefore, in its second article, the Faro Convention defines cultural heritage as “a group of resources inherited from the past which people identify, independently of ownership, as a reflection and expression of their constantly evolving values, beliefs, knowledge, and traditions. It includes all aspects of the environment resulting from the interaction between people and places through time”.

Although the scholarly literature on participation in cultural heritage has been growing since the Faro Convention, there are very few systematic literature reviews to date studying the application of participation in the cultural heritage sector. This highlights the need for an updated systematic study of the current uses of participation in cultural heritage. The relevance of our review is twofold. First, given the importance attributed by many stakeholders to participation, we aim to offer the reader balanced, rigorous key elements about participation, which can be used in cultural heritage as well as other disciplines. Second, through the systematic review, we aim to make the extant body of knowledge on the research questions more transparent, without biases that can be caused by non-systematic reviews. The review was completed in accordance with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines. PRISMA is an evidence-based minimum set of items for reporting in systematic reviews and meta-analyses. In our work, we used PRISMA as a basis for reporting the systematic review with objectives to answer research questions, rather than evaluating interventions (as it is primarily used for). We used an up-to-date tool recommended by the scientific community: PRISMA 2020.

Although the scholarly literature on participation in cultural heritage has been growing since the Faro Convention, there are very few systematic literature reviews to date studying the application of participation in the cultural heritage sector. This highlights the need for an updated systematic research of the current uses of participation in cultural heritage. The relevance of this research is twofold. First, given the importance attributed by many stakeholders to participation, the researchers aim to offer the reader balanced, rigorous key elements about participation, which can be used in cultural heritage as well as other disciplines. Second, the researchers aim to make the extant body of knowledge on the research questions more transparent, without biases that can be caused by non-systematic reviews. The research was completed in accordance with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines. PRISMA is an evidence-based minimum set of items for reporting in systematic reviews and meta-analyses. The researchers used PRISMA as a basis for reporting the research with objectives to answer research questions, rather than evaluating interventions (as it is primarily used for). They used an up-to-date tool recommended by the scientific community: PRISMA 2020.

The analysis focuses on English language scientific papers to (1) redraft a definition of participation, (2) identify the actors of participation, and (3) identify the challenges of participation. This study is motivated by the following three research questions (RQ):

The analysis focuses on English language scientific papers to (1) redraft a definition of participation, (2) identify the actors of participation, and (3) identify the challenges of participation. This research is motivated by the following three research questions (RQ):

-

RQ1: What is participation?

- RQ2: Who are the actors involved in participation?

- RQ3: What are the challenges faced by the actors of participation?

2. Current Insights

Although it is more frequent in academic studies to define participation by its dimension, it remains controversial for two reasons. The first reason is the ambiguity between social participation and political participation. Indeed, the definition of social and political participation is the result of two different academic positions. The first position is “Political participation is a form of social participation”. Political participation involves decision making in social groups and the distribution of resources [83]. These decisions are services rendered by certain groups (e.g., political parties) or by individuals alone in a collective context. In addition to time and special skills, additional resources such as social knowledge and social skills are shared [84]. The second position is “political participation as a different form of social participation”. This scientific positioning is rather more recent than the previous positioning [19].

Although it is more frequent in academic studies to define participation by its dimension, it remains controversial for two reasons. The first reason is the ambiguity between social participation and political participation. Indeed, the definition of social and political participation is the result of two different academic positions. The first position is “Political participation is a form of social participation”. Political participation involves decision making in social groups and the distribution of resources [2]. These decisions are services rendered by certain groups (e.g., political parties) or by individuals alone in a collective context. In addition to time and special skills, additional resources such as social knowledge and social skills are shared [3]. The second position is “political participation as a different form of social participation”. This scientific positioning is rather more recent than the previous positioning [4].

Although participation is a dynamic process between several actors, this process is characterized by the dimension, the actors, the approach, and the context it entails. This is the reason for which we emphasize that defining participation by approach brings more elements of detail to the definition itself. We define participation as the broad term that includes all the participatory approaches with different levels of (non)inclusivity of different actors. We consider that the more that participation is based on an inclusive approach, the more that the actors feel included and collaborate actively within the framework of collective activity. In regard to the context, which can be temporal or spatial, it depends on every case study.

Although participation is a dynamic process between several actors, this process is characterized by the dimension, the actors, the approach, and the context it entails. This is the reason for which the researchers emphasize that defining participation by approach brings more elements of detail to the definition itself. The researchers define participation as the broad term that includes all the participatory approaches with different levels of (non)inclusivity of different actors. The researchers consider that the more that participation is based on an inclusive approach, the more that the actors feel included and collaborate actively within the framework of collective activity. In regard to the context, which can be temporal or spatial, it depends on every case study.

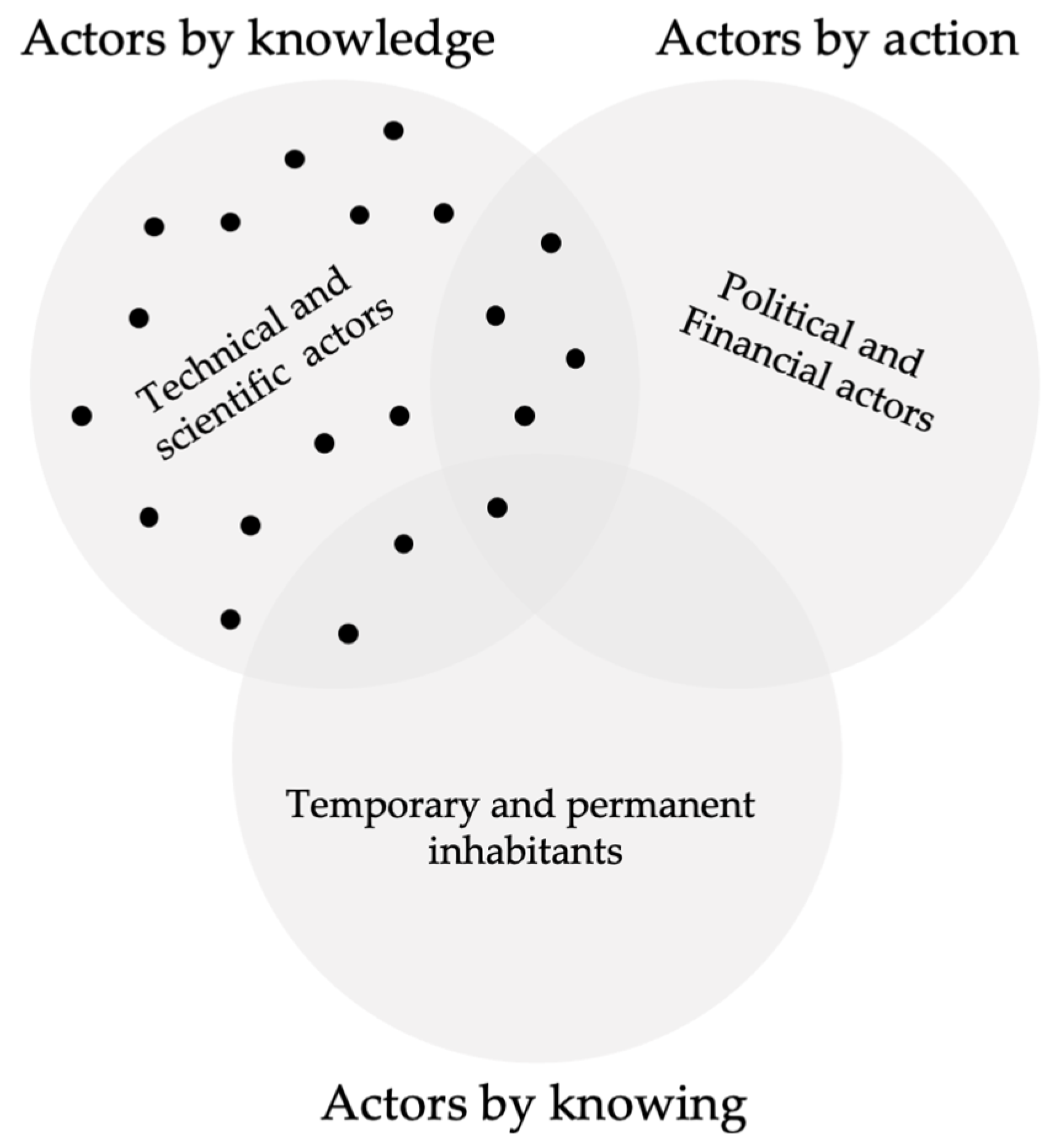

About participation actors, the research disagreement of whether to consider political participation as a form of social participation can influence our pre-categorization of actors by making the boundaries between categories more ambiguous, especially in regard to scientific actors and other actors at the intersections of categories. To avoid this ambiguity and to propose a more developed categorization, we suggest addressing the subject of actors from a different perspective: legitimacy. Our choice of legitimacy to address the subject of actors of participation is based on (1) the definition of legitimacy by Suchman [85] as “ the community’s perception that an actor’s actions will be acceptable and useful for the community” and (2) the definition of an actor’s capacity to interact by Battilana et al. [86] as “the capacity for an actor to interact with other members of the ecosystem depends on the actor’s acknowledged legitimacy within the ecosystem itself”. The two definitions of legitimacy allow us to evaluate the kind of legitimacy that each actor of participation has, in general, and that each actor of participation in cultural heritage has, in particular. Financial actors and political actors can be classified together as actors who have legitimacy by the action. Since they are the actors who have political and financial power, the actions that financial actors and political actors take are acceptable by the rest of the actors, which makes these two categories actors by action. Regarding cultural heritage, actors by action are those who are most likely to change (or not) the material situation(s) of the cultural heritage. Concerning social actors, their legitimacy comes from knowing their immediate context. Since they are the actors who live in the context of the question, they are acceptable by the rest of the actors for knowing their environment. As to cultural heritage, actors by knowing are those who are most likely to have non-institutional knowledge or to take non-institutional action on the cultural heritage. The experts form together another type of actor, whose legitimacy comes from expertise, or knowledge, whether it is technical or scientific. Their expertise, because it is institutional, is acceptable by the rest of the actors. In cultural heritage, actors by knowledge are those who have institutional knowledge and are allowed to take institutional action, if allied to the actors by action, in the cultural heritage.

About participation actors, the research disagreement of whether to consider political participation as a form of social participation can influence the researchers' pre-categorization of actors by making the boundaries between categories more ambiguous, especially in regard to scientific actors and other actors at the intersections of categories. To avoid this ambiguity and to propose a more developed categorization, the researchers suggest addressing the subject of actors from a different perspective: legitimacy. The researchers' choice of legitimacy to address the subject of actors of participation is based on (1) the definition of legitimacy by Suchman [5] as “ the community’s perception that an actor’s actions will be acceptable and useful for the community” and (2) the definition of an actor’s capacity to interact by Battilana et al. [6] as “the capacity for an actor to interact with other members of the ecosystem depends on the actor’s acknowledged legitimacy within the ecosystem itself”. The two definitions of legitimacy allow the researchers to evaluate the kind of legitimacy that each actor of participation has, in general, and that each actor of participation in cultural heritage has, in particular. Financial actors and political actors can be classified together as actors who have legitimacy by the action. Since they are the actors who have political and financial power, the actions that financial actors and political actors take are acceptable by the rest of the actors, which makes these two categories actors by action. Regarding cultural heritage, actors by action are those who are most likely to change (or not) the material situation(s) of the cultural heritage. Concerning social actors, their legitimacy comes from knowing their immediate context. Since they are the actors who live in the context of the question, they are acceptable by the rest of the actors for knowing their environment. As to cultural heritage, actors by knowing are those who are most likely to have non-institutional knowledge or to take non-institutional action on the cultural heritage. The experts form together another type of actor, whose legitimacy comes from expertise, or knowledge, whether it is technical or scientific. Their expertise, because it is institutional, is acceptable by the rest of the actors. In cultural heritage, actors by knowledge are those who have institutional knowledge and are allowed to take institutional action, if allied to the actors by action, in the cultural heritage.

In the following

Figure 3, we reorganize the actors into three different groups according to the legitimacy they have. This serves later to draw the participation challenges.

1, the researchers reorganize the actors into three different groups according to the legitimacy they have. This serves later to draw the participation challenges.

Figure 31. Categorization of actors of participation.

Categorization of actors of participation.

Challenges of Participation: How Are Participation Actors Interacting?

Challenges of participation are commonly addressed in academic studies according to the discipline of study. In cultural heritage, since participation is recent in application, there are fewer studies than other disciplines about the challenges of participation. Based on the crucial roles that actors of participation play, the researchers base their definition of the challenges of participation on the challenges faced by actors when they interact. In this section, the researchers present the challenges of participation based on their ‘How’ question, then focus on the recurrence of participation challenges in cultural heritage.

Challenges of Participation: How Are Participation Actors Interacting?

Challenges of participation are commonly addressed in academic studies according to the discipline of study. In cultural heritage, since participation is recent in application, there are fewer studies than other disciplines about the challenges of participation. Based on the crucial roles that actors of participation play, we base our definition of the challenges of participation on the challenges faced by actors when they interact. In this section, we present the challenges of participation based on our ‘How’ question, then we focus on the recurrence of participation challenges in cultural heritage.

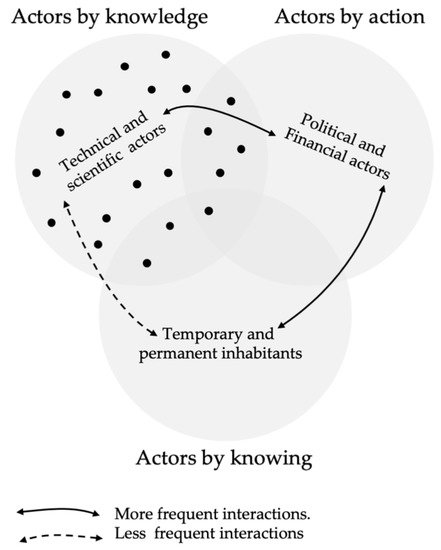

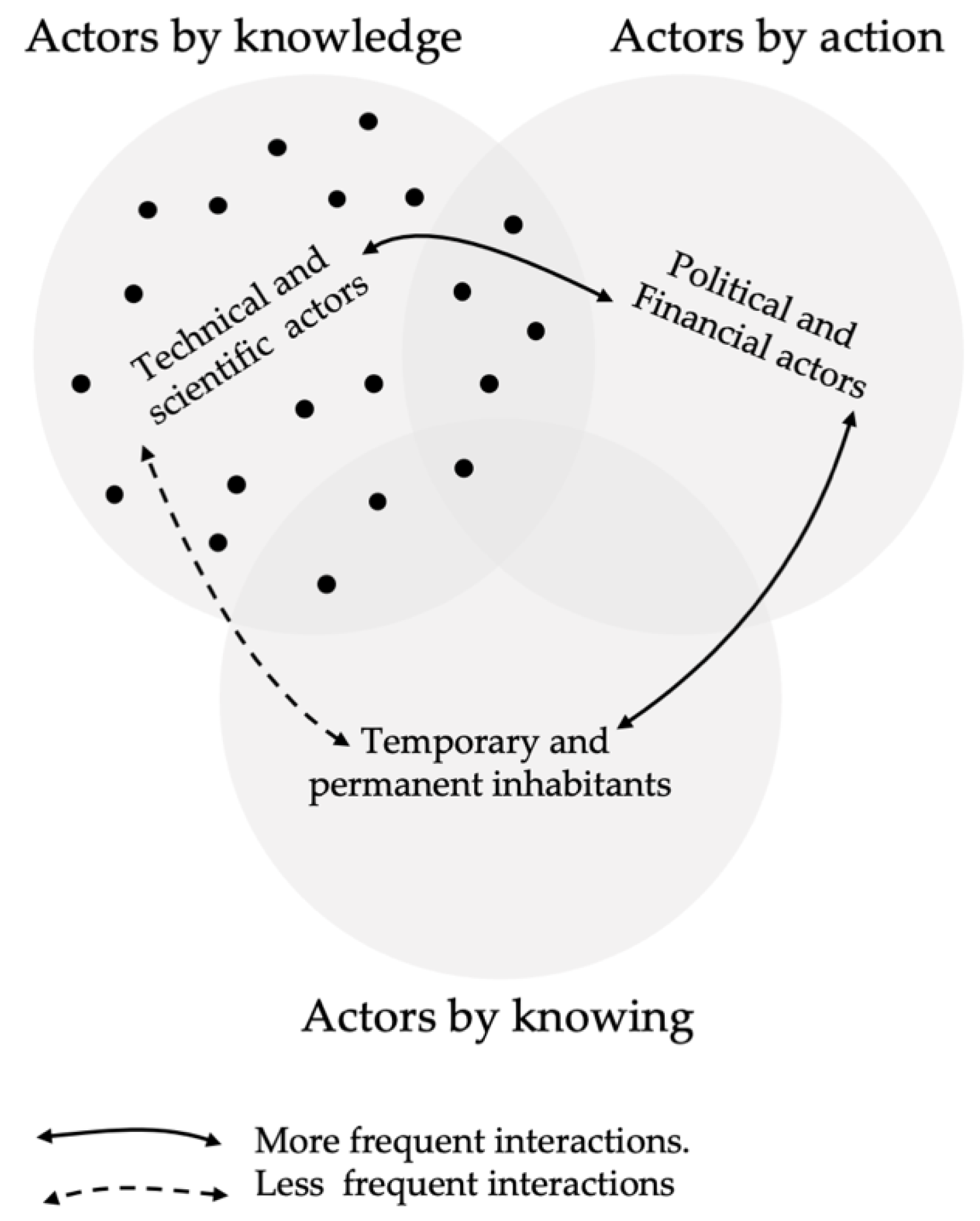

As we mentioned in the method, we chose papers in both multidisciplinary fields (sub-search A) and cultural heritage (sub-searches B and C). Therefore, it was often difficult to spot common categories of participants. It was, however, possible to see clear types of connections that relate to participants who are frequently mentioned in studies about social participation and in studies about participation in cultural heritage. Based on the findings on RQ2 and the definition of an actor’s capacity to interact [86], we deduced the following interactions between the actors, as represented in

The researchers chose papers in both multidisciplinary fields (sub-search A) and cultural heritage (sub-searches B and C). Therefore, it was often difficult to spot common categories of participants. It was, however, possible to see clear types of connections that relate to participants who are frequently mentioned in studies about social participation and in studies about participation in cultural heritage. Based on the findings on RQ2 and the definition of an actor’s capacity to interact [6], the researchers deduced the following interactions between the actors, as represented in

Figure 4 below.

2 below.

Figure 42. Interactions between actors of participation.

In the dynamic between these actors, it is remarkable that interactions between actors by action and actors by knowledge are frequent. These interactions take place through representation and governance processes. Regarding interactions between actors by action and actors by knowledge, they are also frequent, through spaces and territories planning processes. The third possible interaction, between actors by knowing and actors by knowledge, is less frequent than other interactions. This interaction most likely takes place during research projects based on academic and scientific collaborations.

Therefore, these three interactions are mainly based on two axes: democracy and science. Representation and governance processes interactions can be described as democracy interactions between the actors by knowing and the actors by action. Research projects within academic and scientific collaborations can be described as science interactions between the actors by knowledge and the actors by knowing. Finally, spaces and territories planning processes can be described as both democracy and science interactions between the actors by knowledge and the actors by action.

Hence, the main challenges regarding participation in general, and to participation in cultural heritage in particular, take two forms: democracy and science. That is, we acknowledge the existence of two main challenges: the democratic challenge and the scientific challenge. First, the democratic challenge is present in the interactions requiring participation in democratic practices, mainly in the representation and governance processes and partially in the spaces and territories planning processes. In this challenge, the most legitimate actors are actors by action, then actors by knowledge, and then actors by knowing. The democratic challenge is to consider that the non-institutional actions of the actors by knowing are as acceptable and useful for the community as the other actors’ actions. The scientific challenge is present in the interactions requiring participation in science practices, mainly in research projects, and partially in the spaces and territories planning processes. In this challenge, it is more likely in society today to consider that the most legitimate actors are actors by knowledge, then actors by action, and then actors by knowing. The scientific challenge is to consider that the non-institutional knowledge of the actors by knowing is as acceptable and useful for the community as the other actors’ knowledge.

In sub-search A, among 61 papers selected, only 5 studies were connected to the scientific challenge of participation [9,10,29,41,49], whereas in sub-search B and sub-search C, a significant number of the papers selected underline the scientific challenge as the key challenge in the cultural heritage studies selected for this literature review. Out of a total number of 16 papers, scientific challenge is present in 6 studies together with democratic challenge and in 9 studies as the main challenge. The democratic challenge is only underlined in 1 study, as explained in the

Interactions between actors of participation.

In the dynamic between these actors, it is remarkable that interactions between actors by action and actors by knowledge are frequent. These interactions take place through representation and governance processes. Regarding interactions between actors by action and actors by knowledge, they are also frequent, through spaces and territories planning processes. The third possible interaction, between actors by knowing and actors by knowledge, is less frequent than other interactions. This interaction most likely takes place during research projects based on academic and scientific collaborations.

Therefore, these three interactions are mainly based on two axes: democracy and science. Representation and governance processes interactions can be described as democracy interactions between the actors by knowing and the actors by action. Research projects within academic and scientific collaborations can be described as science interactions between the actors by knowledge and the actors by knowing. Finally, spaces and territories planning processes can be described as both democracy and science interactions between the actors by knowledge and the actors by action.

Hence, the main challenges regarding participation in general, and to participation in cultural heritage in particular, take two forms: democracy and science. That is, the researchers acknowledge the existence of two main challenges: the democratic challenge and the scientific challenge. First, the democratic challenge is present in the interactions requiring participation in democratic practices, mainly in the representation and governance processes and partially in the spaces and territories planning processes. In this challenge, the most legitimate actors are actors by action, then actors by knowledge, and then actors by knowing. The democratic challenge is to consider that the non-institutional actions of the actors by knowing are as acceptable and useful for the community as the other actors’ actions. The scientific challenge is present in the interactions requiring participation in science practices, mainly in research projects, and partially in the spaces and territories planning processes. In this challenge, it is more likely in society today to consider that the most legitimate actors are actors by knowledge, then actors by action, and then actors by knowing. The scientific challenge is to consider that the non-institutional knowledge of the actors by knowing is as acceptable and useful for the community as the other actors’ knowledge.

In sub-search A, among 61 papers selected, only 5 studies were connected to the scientific challenge of participation [7][8][9][10][11], whereas in sub-search B and sub-search C, a significant number of the papers selected underline the scientific challenge as the key challenge in the cultural heritage studies selected for this research. Out of a total number of 16 papers, scientific challenge is present in 6 studies together with democratic challenge and in 9 studies as the main challenge. The democratic challenge is only underlined in 1 study, as explained in the

1 below.

Table A4: Charting Challenges of Participation).

Table 21.

Number of studies linked to democratic challenge and scientific challenge in sub-search B and sub-search C.

| Scientific Challenge + Democratic Challenge | Scientific Challenge Only | Democratic Challenge Only |

|---|

| [70,74,75, | ,79] | [76] |

| [12][13][14 | ||

| 80, | ||

| ][ | ||

| 81, | ||

| 15][ | ||

| 82] | ||

| 16][17] | ||

| [ | 67,68,69,71,72, | |

| [18] | ||

| 73 | , | |

| [ | 19] | |

| 77 | , | |

| [ | 20][21][22][23][24] | |

| 78 | ||

| [ | 25][26] | [27] |