1. Introduction

In the wake of the Industry 4.0 development, the concept of Smart Factories and related technologies such as Cyber–Physical Systems (CPS) or the application of Internet of Things (IoT) in an industrial context emerged in the span of just ten years. Cyber–Physical Systems combine the analogue or physical production world with the digital world in a newfound complexity. Consequently, data and knowledge are playing an increasingly bigger role, supporting and leading to data-driven manufacturing (e.g.,

In the wake of the Industry 4.0 development, the concept of Smart Factories and related technologies such as Cyber–Physical Systems (CPS) or the application of Internet of Things (IoT) in an industrial context emerged in the span of just ten years. Cyber–Physical Systems combine the analogue or physical production world with the digital world in a newfound complexity. Consequently, data and knowledge are playing an increasingly bigger role, supporting and leading to data-driven manufacturing (e.g.,

).

Industry 4.0 has first been published on a larger scale as a (marketing) concept in 2011 at the Hannover fair in Germany. What followed was the backwards view on how to define the previous epochs of Industry 1.0 to 3.0 and their respective historical focus (e.g.,

). Industry 4.0 presents a forward view of how the concept may be used to transform the current production environment and integrate digital solutions to improve aspects such as performance, maintenance, manufacturing of individualized products or to generate transparency over the whole production process or value chain of a company. Zhong et al. (2017) conclude that “Industry 4.0 combines embedded production system technologies with intelligent production processes to pave the way for a new technological age that will fundamentally transform industry value chains, production value chains, and business models”

. The technological advance also requires interaction with and integration of skilled workforces, even though this is often not addressed

. In this light, Industry 4.0 can be further defined as a network of humans and machines, covering the whole value chain, while supporting digitization and fostering real-time analysis of data to make the manufacturing processes more transparent and simultaneously more efficient to tailor intelligent products and services to the customer

. Depending on the type of realization and number of data sources, there might be a requirement for Big Data analysis

.

Intensive research has been conducted on how to make the existing factories “smarter”. In this context, the term “smart” refers to making manufacturing processes more autonomous, self-configured and data-driven. Such capabilities enable, for example, gathering and utilizing of knowledge about machine failures, to enable predictive maintenance actions or ad hoc process adaptations. In addition, the products and services which are manufactured often are aimed to be “smart” too, meaning they contain the means to gather data which may be used to improve functionalities or services through continuous data feedback to the manufacturer.

A generic definition of the term Smart Factory is still difficult, as many authors provide definitions based on their specific research area

. It can be concluded from this that the Smart Factory concept is targeting a multi-dimensional transformation of the manufacturing sector that is still continuing. Based on their analysis, Shi et al. (2020) conclude on four main features of a Smart Factory: (1) sensors for data gathering and environment detection with the goal of analysis and self-organization, (2) interconnectivity, interoperability and real-time control leading to flexibility, (3) application of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies such as robots, analysis algorithms as well as (4) virtual reality to enhance “human–machine integration”

. To target the diversity of topics related to the term Smart Factory, Strozzi et al. (2017) conducted a literature survey of publications between 2007 and 2016 and concluded from more than 400 publications direct relations between smart factories and the topics of real-time processing, wireless communication, (multi)-agent solutions, RFID, intelligent, smart, flexible and real-time manufacturing, ontologies, cloud computing, sustainability and optimization

, identifying main areas but also enablers for a Smart Factory.

The overall question this work tries to answer is “How do Industry 4.0 environments or Smart Factory plants of the future look like and what role does data and knowledge play in this development?” Tao et al., (2019), referencing Zhong et al. (2017)

[4], summarize that “Manufacturing is shifting from knowledge-based intelligent manufacturing to data-driven and knowledge-enabled smart manufacturing, in which the term “smart” refers to the creation and use of data” , summarize that “Manufacturing is shifting from knowledge-based intelligent manufacturing to data-driven and knowledge-enabled smart manufacturing, in which the term “smart” refers to the creation and use of data”

. This shift has to be considered with the help of concepts known from the disciplines of data analytics, knowledge management (KM) and knowledge integration, machine learning and artificial intelligence. It presents a change from “knowledge-based”, explicitly represented, qualitative data to the consideration of quantitative data in which meaningful patterns trigger manufacturing decisions, while being informed by supporting knowledge representations, such as ontologies. Especially the pronounced roles of data and knowledge are key aspects of future manufacturing environments and products.

Before talking more about this change the terms data, information and knowledge as well as knowledge management will be introduced briefly, giving a better background of understanding

: From a knowledge management perspective, the three terms are closely related, whereas data are the basis being formed out of a specific alphabet and grammar/syntax and may be structured, semi-structured or unstructured. Information builds on top of data which are used and interpreted in a certain (semantical) context, while knowledge is interconnected, applied or integrated information and oftentimes relates to a specific application area or an individual. That is why the terms of individual and collective knowledge are important factors for knowledge management, a discipline supporting, e.g., the acquisition, development, distribution, application or storage of knowledge within an organization. Different KM models or processes may be established and manage targeting human, organizational and technological aspects. Frey-Luxemberger gives an overview of the KM field

.

The changes and role of data in manufacturing detailed above, is motivated or required by the rising customer demands of customized or tailored orders

. From an outside perspective the change of market demands requires hybrid solutions which not only focus on the manufacturing of physical devices or products but an accompanying (smart) service

, which is only possible if the product generates data to be analyzed and used for offering said service. At the same time, the interconnected technologies require a change in knowledge management. Bettiol et al. (2020) conclude: “On the one hand advanced, interconnected technologies generate new knowledge autonomously, but on the other hand, in order to really deploy the value connected to data produced by such technologies, firm should also rely on the social dimension of knowledge management dynamics”

. The social dimension will be discussed later when reflecting on the changing role of employees in Smart Factories.

To meet a lot size of one, while offering extensive automated configuration abilities throughout the production process, the Smart Factory has to offer configuration and adaptation possibilities in a scalable way. At the same time these have to be manageable by the human workers, as well as being aligned to the underlying business processes. The realization is only possible by collecting and using data and knowledge throughout the manufacturing and documentation process, as well as by deploying automated data analytics and visualization tools to enable real time management and reconfiguration. It is expected that in the future workers inside Smart Factories will have to fulfill different roles or tasks in different processes or together with (intelligent) machines (e.g.,

). Furthermore, instead of only administering one isolated machine, they will be supporting overarching tasks as the surveying and monitoring of interconnected production machines or plants, as well as flexible automation solutions. This again requires knowledge about inter-dependencies in the production process as well as about consequences for multiple production queues, e.g., in case of a failure of an intermediate machine. In this context the topic of predictive maintenance (e.g.,

) is another major issue, as the gathered data inside the Smart Factory can and has to be used to minimize the times of failures in the more complex manufacturing environment, deploying analytics strategies (e.g.,

) or machine learning algorithms to detect potential failures or maintenance measures. The concept of a digital twin (DT) (e.g.,

[9]) might be used here to fuse data and simulation models to create a real-time digital simulation and forecast the real environment, supporting the early detection of potential problems and real-time reconfiguration.

In the following, the different aspects of a Smart Factory including computing, analytics and knowledge integration perspectives will be discussed in more detail.

) might be used here to fuse data and simulation models to create a real-time digital simulation and forecast the real environment, supporting the early detection of potential problems and real-time reconfiguration.

2. Smart Factory

2.1. Smart Factory Environment

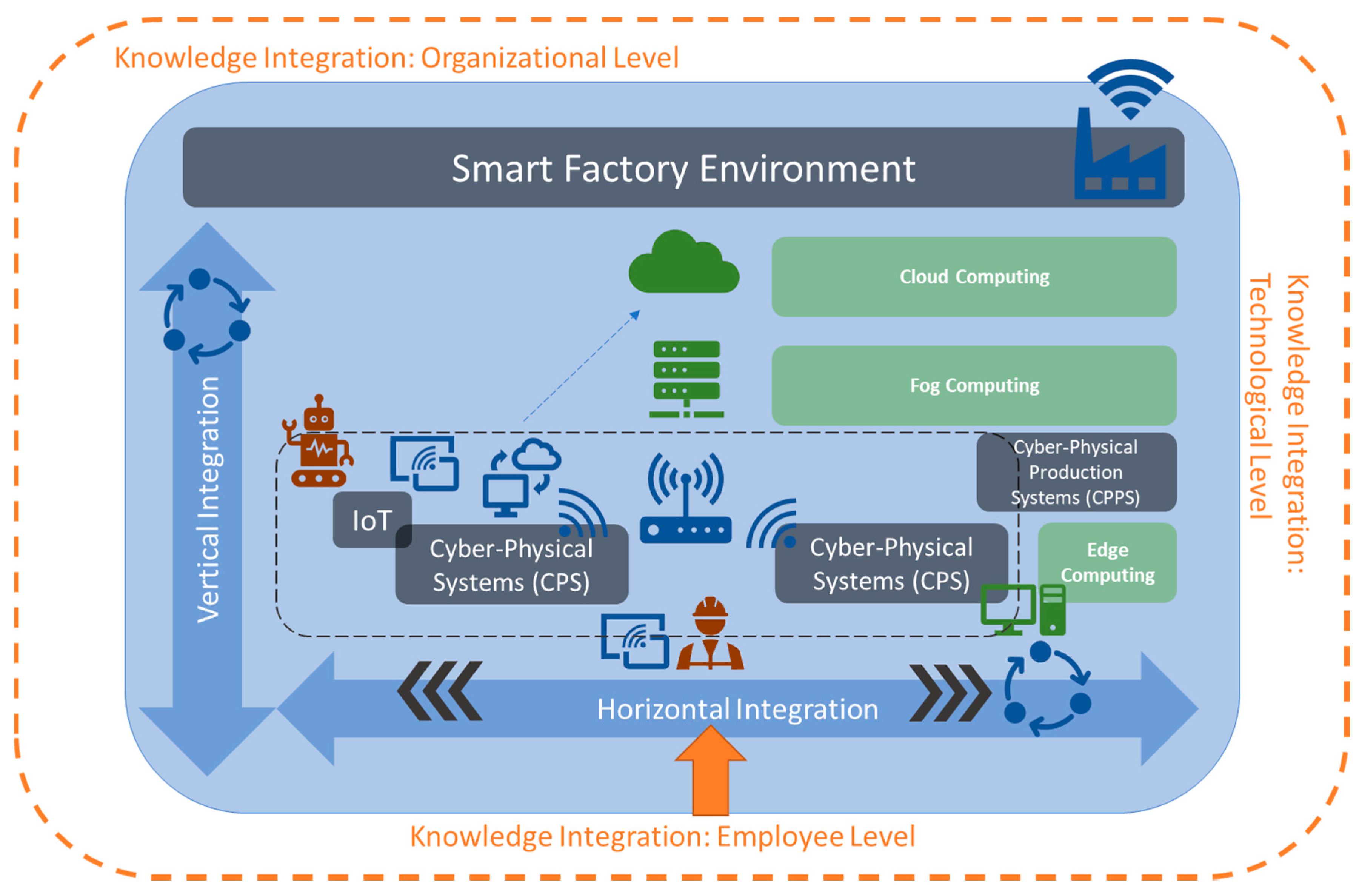

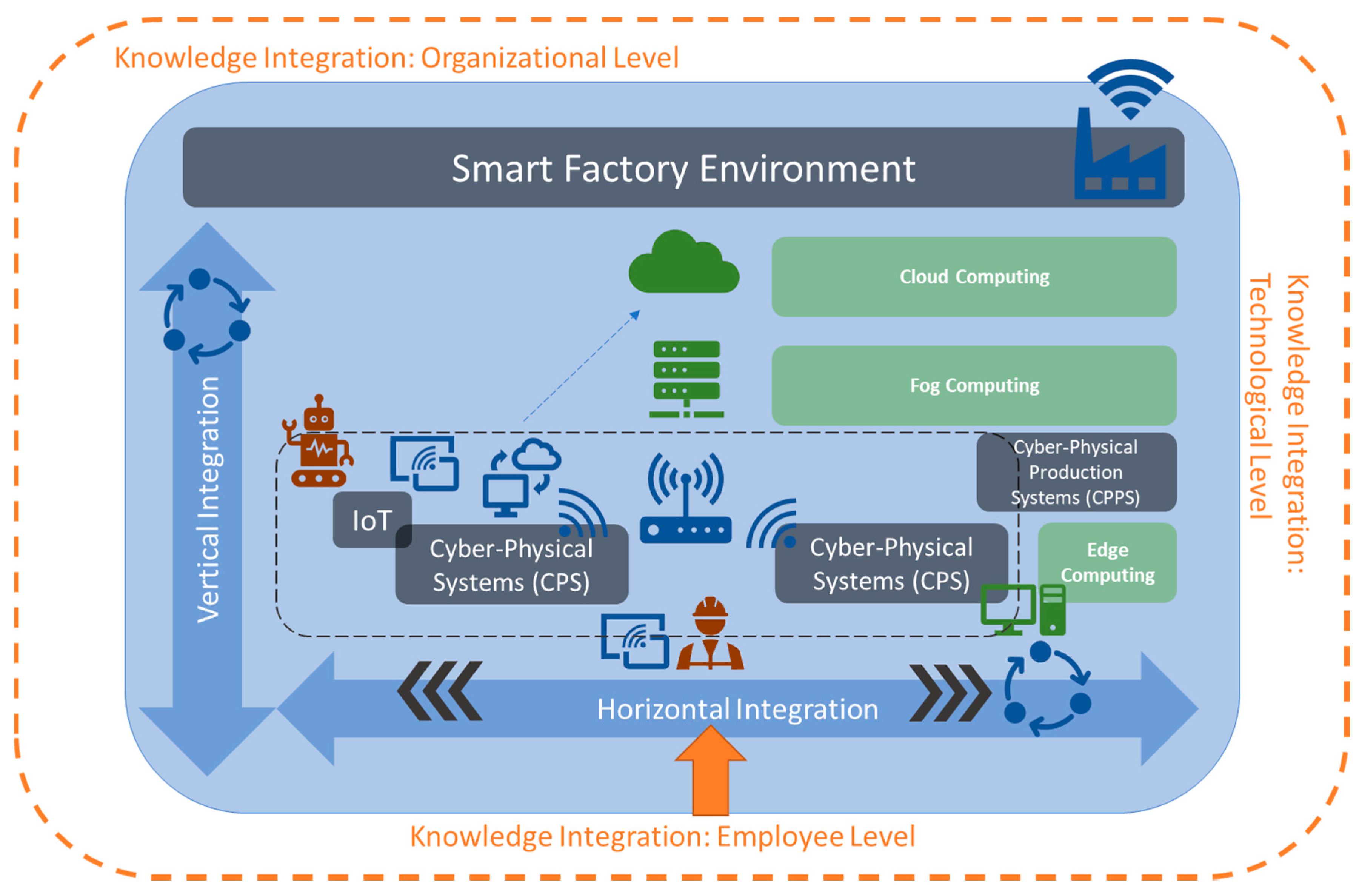

Before the different levels of integration and computing in Smart Factories are explicitly addressed, a conceptual overview of a Smart Factory environment is given and explained. Figure 1 summarizes the integration levels and technologies related to a Smart Factory. The icons indicate the interconnectivity and communication between them and are detailed in the following sub-sections. In this setting, the horizontal perspective is focused on the shop floor level of the manufacturing facilities where products are manufactured, and related data are collected for later integration and analysis. The vertical perspective is a perspective of knowledge integration where gathered data from the manufacturing environment are fused, aggregated and integrated with the knowledge about the underlying business processes. The goal is to derive at the lowest level a real-time perspective on the state of manufacturing, while enabling at the top level a predictive business perspective. These alignments are reflected both horizontally and vertically in the RAMI 4.0 architecture of the i40-platform [17] and vertically in the 5C model [18].

Figure 1. Smart Factory Environment and Knowledge Integration.

Depending on the author, either one or both terms of Cyber–Physical Systems (CPS) or Cyber–Physical Production Systems (CPPS) are used as the main building blocks of a Smart Factory. While the term CPS is sometimes used synonymously with CPPS, the term CPPS is also used to refer to a higher-level system that consists of multiple singular CPS [2][6]. In this paper, we follow the second interpretation. We use the term CPPS to refer to a wider scope, in which interconnected CPSs build the CPPS. In a practical scenario, these may be different production machines connected to one production process, where each machine resembles a unit as an integration of the “cyber”, meaning the computation and networking component, as well as the “physical” electrical and mechanical components. Karnouskos et al. (2019) named autonomy, integrability and convertibility as the main CPPS pillars [19].

Next to CPS or CPPS, other main building blocks are IoT devices, which may be any devices that are able to gather data through embedded sensors as an interconnected entity within a wider network, and subsequently integrating the collected data into the Smart Factory network. This way, previously closed manufacturing environments or passive objects may be transformed into an active role inside the network and, as such, the manufacturing or monitoring processes.

Different communication protocols, technologies and standards may be used for the identification of objects, realization of connectivity or transmission of data, e.g., RFID, WLAN, GPS, OPC UA or specific industrial communication protocols (e.g., [6]). The identification of individual objects inside the production process is essential for individualization of products and automation of processes [20]. Soic et al. (2020) reflect in their work about context-awareness in smart environments that it requires the interconnection of “physical and virtual nodes”, whereas the nodes relate to “an arbitrary number of sensors and actuators or external systems” [21]. Fei et al. (2019) conclude that data gathered from “interconnected twin cybernetics digital system[s]” supports prediction and decision making [22]. Gorodetsky et al. (2019) view “digital twin-based CPPS” as a basis for “real-time data-driven operation control” [23].

IoT architecture models such as the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) architecture published by the Industrial Internet Consortium (IIC) [24] or the RAMI 4.0 architecture of the i40-platform [17] are approaches to standardize the implementation of a Smart Factory from the physical layer up to the application layer similar to the OSI 7 layer model.

Each CPS (e.g., through embedded sensors), or IoT device, produces or gathers data which need to be processed and analyzed to generate immediate actions or further derive knowledge about the status of the devices or the manufacturing process in focus. This may happen directly inside the device or with the help of a local computing device attached to the machine, called edge component and Edge Computing, respectively, on a local network level, called Fog Computing, or with the help of a central Cloud Computing platform. The Cloud Computing solution is beneficial when there are different production plants and the data need to be gathered at one common, yet transparently distributed, place to be analyzed. Edge or Fog Computing are better in cases of immediate processing or processing inside a local plant. In this context, it is important to define if data need to be analyzed immediately, e.g., for monitoring purposes or for cases where an analysis of a specific time frame is necessary. In the first case, Stream Processing or Stream Analytics can be used where the data are gathered and immediately analyzed “in place”, meaning while being streamed, while in the second case Batch Processing or Batch analysis takes place, where data are collected and processed together with the option of aggregating over time and features. In Section 3, the different aspects are discussed in more detail.

2.2. Multi-Dimensional Knowledge Integration in Smart Factories

Theorem 1. From the perspective of Knowledge Management and considering the three associated main pillars of (1) human workforce, (2) organizational structures or processes as well as (3) technology, the establishment of a Smart Factory requires a Multi-dimensional Knowledge Integration Perspective targeting the aforementioned three pillars, while considering the knowledge associated with, as well as the interconnected manufacturing processes and automation requirements to support a “Smart” solution.

Based on Theorem 1, the following sub-sections detail the different aspects of how to create such a multi-dimensional knowledge integration perspective. We consider the human–organization–technology (HOT) (e.g., [10], or [25]) perspectives the target for this multi-dimensional knowledge integration [26]. Examples of the human (employee) perspective are roles like involved knowledge experts, lifelong learning, human–machine interaction, etc. Examples on the organizational perspective are the transformation of a hierarchical into a network-based structure, organizational learning and a data-driven business process integration; and finally, from the technological perspective we have the variance of knowledge assets (e.g., textual content, sensor data) as well as analysis processes, which will be detailed in Section 3.3. Figure 1 summarizes the perspectives around the Smart Factory environment.

3. Knowledge Integration

3.1. Knowledge Integration on Organizational Level: Horizontal and Vertical Integration

The Smart Factory integration or transformation from a regular factory into a Smart Factory bases on a horizontal and a vertical integration perspective. The horizontal perspective targets the production and transportation processes along the value chain, while the vertical perspective has a look at how the “new” or “transformed” production environment fits and interrelates with the other organizational areas such as production planning, logistics, sales or marketing, etc. The platform i4.0 visualized this change between Industry 3.0 [27] towards Industry 4.0 [28] with the change from a production pyramid towards a production network. Hierarchies are no longer as important in Industry 4.0 as the concept transforms the organization into an interconnected network, where hierarchical or departmental boundaries are resolved or less significant. The important aspect is the value chain and all departments working towards customer-oriented goals. This of course requires a change in the way the employees work and interact with each other. While before employees in the same hierarchy level or working on the same subject were mostly communicating with each other, this organizational change also leads to a social change inside the company. In addition, job profiles are changing towards a “knowledge worker”. This will be discussed in Section 3.3.2 as it requires knowledge management aspects to support this change process.

Going back to the horizontal and vertical integration, both aspects are not only related to the organizational changes necessary to establish a Smart Factory. They also target the data perspective. Data play a central role for the Smart Factory, as it is needed to automate processes or exchange information between different manufacturing machines or between divisions as production and logistics, etc. These data are gathered mostly with the help of sensors, embedded into IoT devices which are part of the CPS. A sensor might be attached directly at a specific manufacturing machine or at different gates where the products or pre-products come along during their way through the manufacturing environment. RFID tags may be used to automatically scan a product, check its identity and update the status or next manufacturing step. If the data are gathered and analyzed along the manufacturing process, then they are part of the horizontal integration, as the results of analysis might directly influence the next production steps and focus on a real-time intervention. Data analytics [16] from a vertical perspective have a broader focus and gather and integrate data from and at different hierarchical levels and different IT systems, as, e.g., the enterprise resources planning (ERP) system, as well as over a longer time period to, e.g., generate reports about the Smart Factory or a specific production development for a specified time.

3.2. Knowledge Integration: Employee Level

If we consider the organizational changes leading to a Smart Factory, it is important to consider the role of the current and future employees in this environment. This applies especially to those employees whose production environments have been analogue or not interconnected before and who now need to be part of the digitized production process. As such, an essential factor in this transformation process is lifelong learning and needs to be considered in all knowledge management activities of the Smart Factory [29].

From the perspective of knowledge integration, it is recommended to involve knowledge engineers or managers to support the transformation process but to also consider the concerns or problems the employees have and to acquire and provide the training they need. Another aspect is to establish the knowledge exchange between different involved engineering disciplines, as well as computer science for the design and understanding of complex systems such as CPS.

The employees in Smart Factories may be concerned about their future role and tasks as there will be continuous shifts in human–machine interaction (HMI), where the mechanized counterparts of a human worker in the future may be different CPS, a robot or an AI application. The roles that workers execute may be the controller of a machine, peer or teammate up to their replacement by an intelligent machine [30]. Ansari, Erol and Shin (2018) differentiate HMI into human–machine cooperation and human–machine collaboration in the Smart Factory environment: “A human labor on the one side is assisted by smart devices and machines (human–machine cooperation) and on the other should interact and exchange information with intelligent machines (human–machine collaboration)” [14]. This differentiation indicates that the human worker has benefits which will make their work process easier due to assisted technical and smart solutions, but also pose challenges as the worker needs to learn to work together with this new technical and digitized work environment. Vogel-Heuser et al. (2017) highlight that the human worker is now interconnected with CPS with the help of multi-modal human–machine interfaces [29]. The automation and application of AI are factors which question (a) the role of the human worker in the work process as well as (b) their abilities in decision making as it might be influenced by or contrary to the recommendations or actions of the AI application. An AI “would always base its decision-making on optimizing its objectives, rather than incorporating social or emotional factors” [15], posing a challenge of who is the main decision maker in the Smart Factory and if the explicit and implicit knowledge and experience of the human worker are more valuable than the programmed AI logic, e.g., based on data and the execution of machine learning algorithms. Seeber et al. (2019) resume that “The optimal conditions for humans and truly intelligent AI to coexist and work together have not yet been adequately analyzed”, leading to future challenges and requirements to create recommendations or standards for said coexistence and collaboration between human and machine teammates [15]. One approach is a “mutual learning” between human and machine, supported by human acquisition, machine acquisition, human participation and machine participation leading to the execution of shared tasks between human and machine [14]. North, Maier and Haas (2018) envision that “in the future expertise will be defined as human (expert) plus intelligent machine”, with the challenge being how they learn and work together [30]. A possible system, showcasing this synergetic collaboration is the implementation of cobots, passive robots that are tailored for collaboratively inhabiting a shared space for the purpose of operating processes together with humans [31].

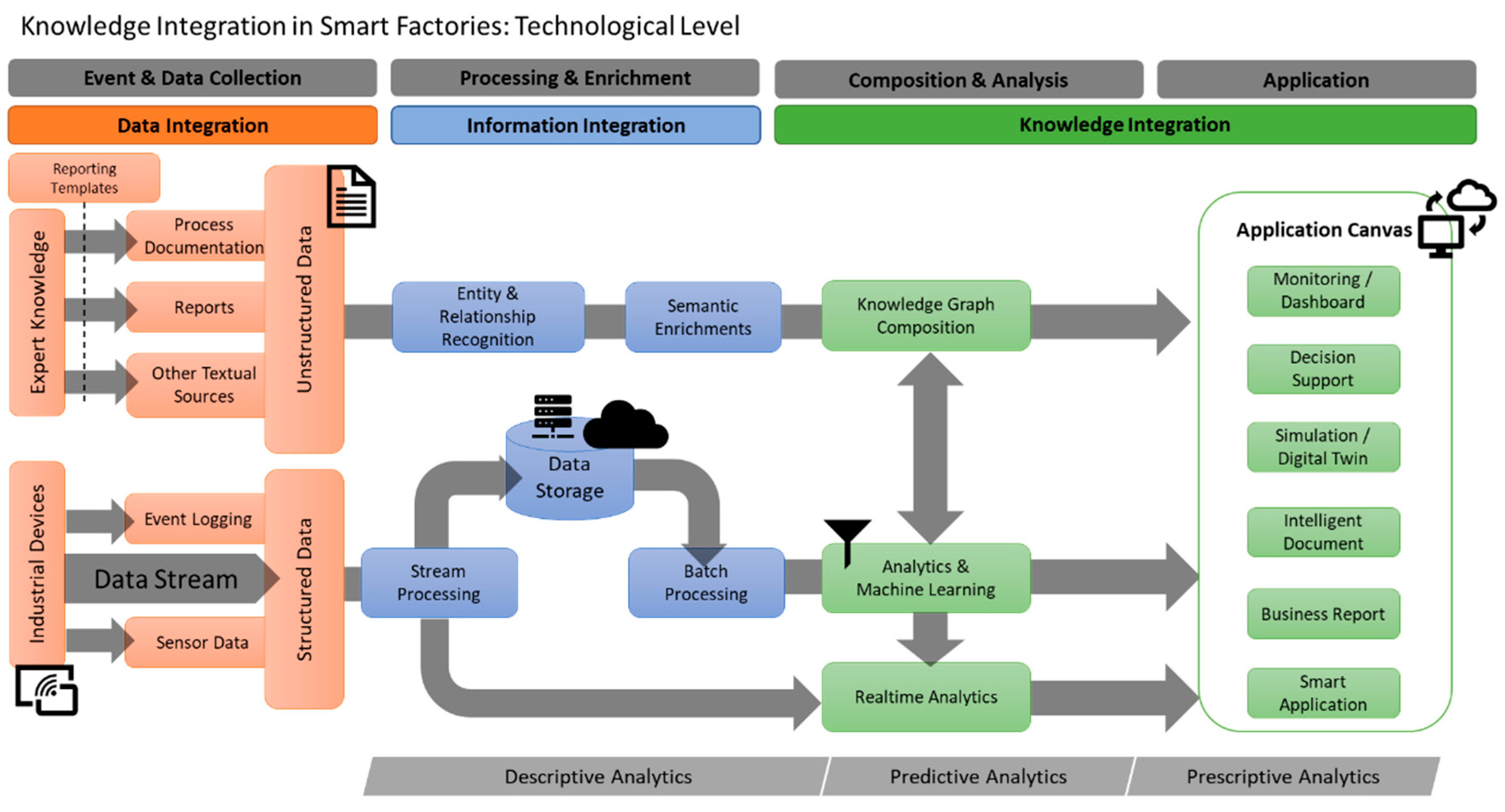

3.3. Knowledge Integration: Technological Level

In the introduction, the central role of data and knowledge in modern manufacturing has been motivated. Tao et al. are even speaking of “data-driven smart manufacturing” [1]. This means a continuous generation of data streams, leading to big data which require processing and analysis [2]. The following Table 1 summarizes how these data may be used or processed to generate knowledge inside the Smart Factory.

Table 1. Overview of Knowledge Integration on a Technological Level.

| Knowledge Processing |

Realization in Smart

Factory |

Benefits |

Exemplary

Technologies 1 |

Data

Computing/

Processing |

Cloud Computing |

Software as a Service (SaaS), central software applications without local installation |

Amazon AWS, Microsoft Azure |

| Fog Computing |

Enhance low-latency, mobility, network bandwidth, security and privacy |

Cisco IOx |

| Edge Computing |

Offload network bandwidth, shorter delay time (latency) |

Cisco IOx, Intel IOT solutions, Nvidia EGX |

| Data Analytics |

Descriptive Analytics |

Status and usage monitoring, reporting, anomaly detection and diagnosis, modeling, or training |

RapidMiner, RStudio Server, Tableau |

| Stream Analytics: Real-Time Analysis |

Apache Kafka/Flink, Elasticsearch and Kibana |

| Batch Analytics: Monitoring/Reporting |

Apache Spark/Zeppelin, Cassandra, Tensorflow, Keras |

| Predictive Analytics |

Predicting capacity needs and utilization, material and energy consumption, predicting component and system wear and failures |

RapidMiner, RStudio Server, Tensorflow, Keras, AutoKeras, Google AutoML |

| Prescriptive Analytics |

Guidance to recommend operational changes to optimize processes, avoid failures and associated downtime |

RapidMiner, RStudio Server, Tensorflow, Keras, AutoKeras, Google AutoML |

| Simulation |

Digital Twin Concept |

Real-time analysis, simulation of scalable products and product changes, wear and tear projection |

MATLAB Simulink, Azure Digital Twins, Ansys Twin Builder |

| Semantic Knowledge Representation |

Knowledge Graphs |

Contextualization of multi-source data,

Semantic relational learning |

Neo4j, Grakn, Ontotext GraphDB, Eccenca corporate memory, Protégé |

| Text Mining |

Intelligent Documents |

Integration of lessons learned from reporting and failure logs in new design or production cycles |

tm (R), nltk (Python), RapidMiner, Text Analytics Toolbox (MATLAB), Apache OpenNLP, Stanford CoreNLP |