Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Amina Yu and Version 1 by Kariem Ezzat.

Protein aggregation into amyloid fibrils affects many proteins in a variety of diseases, including neurodegenerative disorders, diabetes, and cancer. Physicochemically, amyloid formation is a phase transition process, where soluble proteins are transformed into solid fibrils with the characteristic cross-β conformation responsible for their fibrillar morphology.

- amyloid

- prion

- Alzheimer’s

- Parkinson’s

- Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD)

1. What Are Amyloids?

Proteins, like any other molecules, can exist in different states or phases depending on their packing density. Similar to gas, liquid, and solid phases of water, for example, (water vapor, liquid water, and ice), proteins can be soluble or colloidally dispersed in the aqueous biological environment, concentrated in liquid droplets that form a separate liquid phase within the aqueous environment, or in a tightly packed solid state. The liquid–liquid phase separation of proteins has been intensively investigated and reviewed recently [1,2][1][2]. Here,It weas focused on amyloids as specific form of protein solids.

There are two main types of protein solids that form in-vivo:

-

Fibrous proteins, such as actin, elastin, and collagen;

-

Amyloids, which are associated with many human diseases.

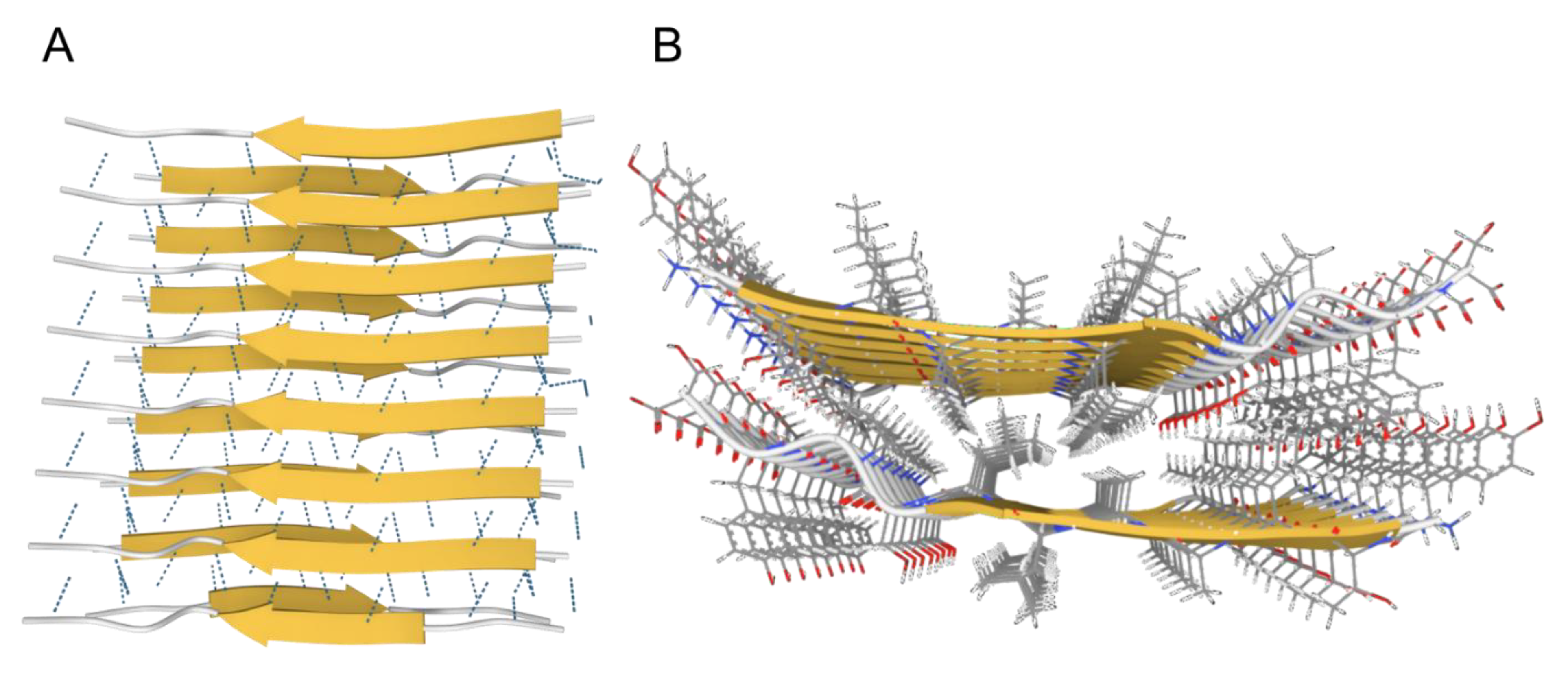

While both types of in vivo protein solids share similar physicochemical mechanisms of formation (nucleation and growth, see below), they differ in many fundamental ways. Fibrous proteins, such as actin or collagen fibers, are formed from a specific group of proteins, where the monomers (for examples G-actin and tropocollagen for actin and collagen fibers, respectively) are natively folded before assembling into fibers in a controlled and reversible manner, which involves energy-dependent processes (enzymes and ATP) [3,4,5][3][4][5]. In contrast, amyloid fibrils can be formed by almost any amino acid sequence, from globular nonfibrous proteins, such as myoglobin [6], insulin [7], and albumin, [8] to simple polylysines, polyglutamates, and polythreonines sequences [9]. Such generic nature- and sequence-independence indicate that the architecture of the amyloid state is not encoded in the primary sequence of proteins [10,11,12,13][10][11][12][13]. Unlike native protein folding, which depends on specific intramolecular interactions between the side chains of a particular sequence, the structure of the amyloid state is dominated by intermolecular interactions via the backbone that is common to all proteins. Consequently, amyloids from different proteins possess a common core conformation, the cross-β conformation, where intermolecular β-sheets pair tightly together with their side chains interdigitating (like zipper teeth) excluding water to form the so-called “dry steric zipper” (Figure 1) [14,15,16,17,18][14][15][16][17][18]. The intermolecular β-sheets form via a generic interbackbone hydrogen-bonding network between the amide N-H and C=O groups of adjacent protein molecules [19] and can comprise up to thousands of molecules extending for µm distances [14]. Within the β-sheet ladder, β strands are spaced 4.8 A° and the distance between opposite β sheets are in the range of 6–12 A° (Figure 1), which gives rise to the characteristic amyloid X-ray diffraction pattern with meridional and equatorial reflections of similar values, respectively [16,18][16][18]. Extended ladders of interdigitating β-sheet pairs form the core spine of the superstructural subunit of amyloids, the protofilament. A protofilament can accommodate a single or multiple steric zippers in different arrangements with different mating/interdigitation options between the side chains of the constituting ladders [15]. Protofilaments further associate laterally into fibrils, which further associate and precipitate as insoluble plaques, characteristic of tissues affected by amyloidosis [20].

Figure 1. The cross-β conformation of amyloids. (A). Side-view showing the intermolecular β-sheets stabilized by hydrogen bonds (dotted lines). (B). Top-view showing the dry steric zipper between the two opposing β-sheets with interdigitating sidechains. Images created using Mol* [21] from PDB structure 2M5N from paper by Fitzpatrick et al., 2013 [22].

Another major difference between native protein folding and the cross-β conformation of amyloids is that the interdigitation of side chains between β-sheet ladders generally deprives amyloids from any characteristic domains. Additionally, the extensive, hierarchical self-interaction (ladders within zippers, zippers within protofilaments, protofilaments within fibrils, and fibrils within plaques) makes amyloids very stable and, consequently, extremely difficult to solubilize and relatively inert. The aggregated, plaque nature of amyloids is, again, in contrast with functional fibrous proteins which assemble in well-defined networks by accessory proteins [23]. The difference between functional fibrous proteins and amyloids is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

The differences between fibrous proteins and amyloid fibrils.

| Fibrous Proteins | Amyloid Fibrils |

|---|---|

| Specific proteins | Any protein sequence |

| Monomers assemble in their native conformation via specific intramolecular sidechain-based interactions | Proteins assemble into in cross-β conformation via generic intermolecular backbone interactions |

| Functional domains remain accessible | Majority of functional domains are buried in steric zippers |

| Form well-defined networks | Precipitate into plaques |

| Controlled nucleation and growth via structural elements (proline and glycine rich), capping proteins, specific nucleators, enzymes and ATP | Uncontrolled |

| Reversible | Irreversible |

Despite the universal cross-β conformation of any amyloid, the difference in number or arrangement of steric zippers within a protofilament and/or the number and arrangement of protofilaments within a fibril result in different polymorphs. Unlike the cross-β conformation which is structurally encoded in any protein sequence via generic inter-backbone hydrogen-bonding, polymorphism is dependent on environmental factors such as temperature, pH, concentration, and shaking; extrinsic factors that are not structurally encoded [24]. For example, with the same sequence, different polymorphic shapes of Aβ40 fibrils can be produced in quiescent versus agitating conditions [25], and the presence or absence of polyanions leads to the production of different polymorphs of α-synuclein fibrils [26]. The interaction between environmental factors and the protein sequence affects polymorphism by affecting the patterns of β-sheet ladder stacking and zipper interdigitation, which can also lead to different polymorphs of different sequences under same conditions [15].

As proteins have the information to fold natively in the primary sequence of side chains (Anfinsen’s dogma [27,28][27][28]), they also holds the necessary information to form the cross-β conformation based intermolecular backbone interactions, which requires molecular proximity. This is why amyloid formation requires supersaturated conditions and the likelihood of a protein forming an amyloid increases with concentration [29,30][29][30]. Above a certain concentration, the molecular proximity renders the intermolecular interactions more favorable than intramolecular interactions responsible for native folding, leading to amyloid formation. This intermolecular interaction will result in molecular packing, phase transition, and precipitation out of the aqueous biological environment.

2. How Do Amyloids Cause Toxicity?

Amyloid formation involves three pathological protein transformations: structural, from natively folded to the cross-β conformation; biophysical, from soluble to insoluble; and biological, from functional to non-functional [68][31]. The cross-β conformation buries the once-functional domains of the protein within the steric zipper architecture, which makes amyloids extremely stable [14], and, consequently, relatively inert. Additionally, the uncontrolled phase transition leads to loss of protein solubility and colloidal stability resulting in precipitation into plaques, which further buries any potential unpaired side chains via hierarchal self-interaction (see above). Within plaques, amyloid protofilaments and fibrils adopt different polymorphic morphologies depending on environmental conditions. However, since all polymorphs are based on the same cross-β conformation, where the functional side chain domains are sequestered, they are expected to have similar, generic amyloid properties in terms of stability, insolubility, and low reactivity. Furthermore, the loss of protein solubility and colloidal stability favors precipitation and cluster formation over propagation of single fibrils, which requires colloidal dispersion. This is supported by clinical findings that plaques (heterogenous fibrillar clusters) are the hallmarks of amyloid pathologies.

With the high stability and low reactivity, amyloids pose little direct toxicity unless they physically remodel a tissue, for example, in the rare csituasetions of systemic amyloidosis such as immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis and transthyretin amyloidosis [74,75][32][33]. This is especially true for amyloid accumulation within the muscle tissue (for e.g.xample, cardiac amyloidosis), where amyloid infiltration physically impair muscle contractility [76][34]. However, in many other cases, amyloids exist as a benign mass similar to other benign masses, such as fibromas and lipomas. In insulin-derived amyloidosis, for example, repeated injection of insulin subcutaneously in the same spot leads to the creation of insulin amyloid lumps in some diabetic patients [77][35]. Despite the benign nature of such lumps, patients lose the ability to control glucose levels due to insulin sequestration in the form of amyloid aggregates [78][36]. Patients are, therefore, instructed to change the location of insulin injections to avoid local aggregation. In tThis case, the te toxicity due to amyloid aggregation is due to loss-of-function (LOF) of the injected insulin and not due direct toxicity from the amyloid mass. Pathogenesis due to LOF is also demonstrated in the case offor p53 amyloid formation. P53 is a tumor suppressor protein whose dysregulation or inactivation is involved in more than 50% of all cancers [79][37]. It has been shown that p53 can form amyloid fibrils leading to enhanced cell proliferation due to its sequestration and LOF [80,81][38][39]. These findings clearly indicate that amyloids are not necessarily cytotoxic as they can enhance, not impair, cell proliferation via a LOF mechanism of p53. LOF is also the mechanism behind many phenotypes in yeast due to amyloid formation [82][40]. For example, amyloid formation of Sup35, which is an essential translation termination factor, induces lethality due to LOF as a result of its sequestration in the amyloid state [83][41]. Such an outcome can be reversed by supplying the yeast with a modified version of Sup35, where the residues more prone to amyloid formation are removed, while the domains involved in translation termination are maintained [84][42]. This replacement approach to overcome amyloid LOF toxicity is also utilized clinically in the treatment of diabetes mellites by using pramlintide, which is a less aggregating analogue of the peptide hormone amylin, whose amyloid aggregation in the pancreas and depletion in the circulation is common among diabetic patients [85][43]. The relatively benign nature of amyloid plaques can also be seen in neurodegenerative diseases such as AD, where up 30% of individuals who have plaques in their brains are cognitively normal [86][44]. WeIt havewas recently shown that higher levels of soluble Aβ42 are associated with normal cognition and preservation of brain volume among amyloid positive individuals, regardless of and despite increasing levels of brain amyloid, indicating that LOF of the soluble Aβ42 is more detrimental to neurons than direct gain-of- function (GOF) toxicity from plaques [87][45]. This suggests that a replacement approach might also be feasible for AD treatment and other neurodegenerative diseases, an alternative to continuing with anti-amyloid strategies, which have invariably failed [88][46].

“Toxic oligomers”? Oligomers have been postulated to explain the lack of association between amyloid plaque load and toxicity, especially in AD. The term oligomers denotes low and medium molecular weight aggregates that are assumed to mediate the amyloid toxicity [89][47]. However, the evidence of their toxicity has been shown in vitro, not clinically, and the clinically relevant toxic oligomer remains unknown [90][48]. Moreover, under supersaturated conditions, which are necessary for amyloid formation, the distinction between oligomers and nuclei is hard to make, since the formation of any cluster stable enough will trigger phase transition into fibrils, whereas unstable clusters will dissociate back into monomers (see above). This has been demonstrated experimentally, where the majority of oligomers were shown to dissociate into monomers, in good accordance with the classical nucleation theory [91][49]. Moreover, the reduction of soluble Aβ42 levels during the disease course reduces the substrate for the oligomers, questioning the long-term effect of such species. This is supported by the fact that attempts to quantify oligomeric species of Aβ found that they are less in AD patients compared to controls [92,93,94][50][51][52].

“Ratios”. Despite the progressive decrease in the absolute levels of soluble Aβ42 in AD, the ratio of Aβ42 relative to other shorter versions of the peptide, such as Aβ40, was hypothesized to increase the likelihood of Aβ42 forming aggregates due to its more amyloidogenic nature [95][53]. However, amyloid aggregation is dependent on supersaturation, which is dependent on the absolute concentration of the peptide. Decreasing peptide concentration will decrease, not increase, its propensity to form any type of aggregates irrespective of its relative levels compared to other peptides. Moreover, it has been recently demonstrated that CSF Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio also decreases during the course of AD [72][54].

Another indication on the importance of LOF as a pathogenic mechanism in neurodegenerative diseases is the fact that animal models where the amyloidogenic proteins were knocked out or down display phenotypes that resemble those obtained by protein overexpression and aggregation. This has been demonstrated for Aβ42 [96,97][55][56] in AD, α-synuclein in Parkinson’s disease [98[57][58][59],99,100], and other neurodegeneration-related proteins that form amyloids such as Tau [101][60], PrP [102][61], SOD1 [103][62], and TDP43 [104][63]. The similarity of phenotype in both the presence and absence of aggregates can only be explained by LOF mechanism, where the sequestration of protein due to aggregation mimics the effects of gene knock down. Additionally, in many cases, the phenotype can be rescued by restoration of normal soluble levels of these proteins [97,99][56][58]. For further discussion on LOF toxicity, these weas refer the readerred to our earlier reviews [68,105][31][64].