Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by NISAR ALI KHAN and Version 2 by Rita Xu.

Improving archaeology policies means fostering search and exploration of ancient sites, promoting protection and preservation actions of architectural remains, and management of cultural heritage.

- monuments

- architectural heritage

- archaeological sites

1. Introduction

Historical Background of the Archaeological Conservation in Central Asia

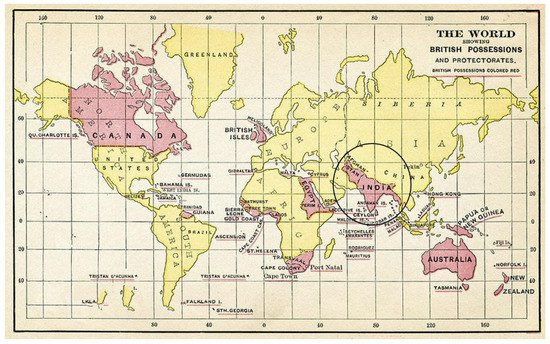

In South Asia, these policies improvements developed in the early 19th Century in the British colonies, shown in Figure 1, i.e., present Pakistan, Bangladesh, India, and Sri Lanka [1][2][1,2]. One of the basic and most significant contributions is the protection of monuments, irrespective of their religious or historical significance. Moreover, the British colonial legacy in the above-mentioned South Asian countries is noticeable in the form of exploration of extensive archaeological sites, preservation of countless monuments, and establishment of museums [3]. Formal recognition of such policies are presented by Bengal Regulation XIX of 1810, according to which, if any public structure is misused by private individuals, the government has its full right to interfere, even though no specific details about the measures to undertake were given [4].

Figure 1. Map of the World, British possessions illustrated in red. The circled area is the study area, i.e., South Asian territory including present Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka. Source: P.J. Mode collection of persuasive cartography, #8548. Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library.

The East India Company decided in the year 1844 to gather detailed information about nature and the existing state of monuments, planning to collect useful information about each temple and building to make an initial report that could be used further for protection and rehabilitation. However, the monuments located in present-day Pakistan were not included in the work undertaken. In 1855, some monuments were repaired including Shah Jhan Mosque and some tombs on Makli Hill, Thatta (Sindh). In 1862, prior to the appointment of Major General Sir Alexander Cunningham as Director-General of Archaeology, repair, and maintenance of ancient buildings were not covered in the financing plan. Sir Cunningham was a civil engineer who had a great interest in the preservation of monuments. Thus, he started a survey to accelerate the recording and documenting of archaeological, historical, and architectural data. Even though there were no specific rules, policies, and schemes mentioned in the archaeological survey, the survey revealed the importance of architectural heritage and monument wealth to the British government [4]. In circular No. 9 of the central government of P.W.D. (Public Work Department) dated 13 February 1873, the provincial (local) governments were given the responsibility to protect all buildings and ancient monuments of architectural and historical interest [4]. An Act was passed in 1878 to protect the sites from damages, which has never been edited or revoked. Lord Lytton, the Viceroy, soon realized the dangers of handing over the responsibility of monuments preservation to the local government and raised such issue to the central government, underlining that it could not be expected from local Lieutenant Governors to combine aesthetic culture with administration energy and that he could not consider any claims more essential and imperial than this [4].

In 1881 Major H.H. Cole was appointed as a member of the Ancient Monuments of India to compile detailed and well-classified lists of monuments in each province. He was assigned to group the monuments according to their status: those to be kept in good permanent condition, those that could be saved from further degradation, and those inevitably ruined [4][5][4,5]. These monuments were later divided into three comprehensive groups I, II, and III, which were the foundation of the classification reported in the Conservation Manual (1923) by Sir John Marshall. The initial report of Sir Cole on the conservation of monuments was printed by the Indian government (Simla–Calcutta 1881–1885). He arranged essential reports in 22 parts and took interest by himself in supervising the conservation and protection of ancient monuments.

After Cole’s tenure in 1883, the task of the preservation and maintenance of monuments returned again to the local government.

In 1899 according to an approved scheme, British India was split into five archaeological circles, which included Sindh, Balochistan, and Punjab (the present part of Pakistan). According to such a scheme, the new Director Generals were supposed to take care of the ancient monuments, their maintenance, rehabilitation, and preservation, when and where required [6]. According to the new government policy, the most important duty of the central government was towards the conservation of ancient monuments [6]. Lord Curzon, appointed as Viceroy in 1899, brought significant changes in the history of archaeological survey. His interest yielded important changes in the rules, regulations, and management policy regarding the preservation and maintenance of monuments. Before the Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal, in February 1899, he clearly defined his objectives about working research, improvements of archaeology, and protection of monuments [5]. It goes also to the credit of Lord Curzon to pass the ancient monuments preservation Act in 1904. His firm support laid a foundation for the development of the management and preservation policy of architectural heritage [5][6][7][8][9][5,6,7,8,9].

2. Pakistan’s Heritage Management

2.1. Heritage Management Pre and Post-Independence of Pakistan

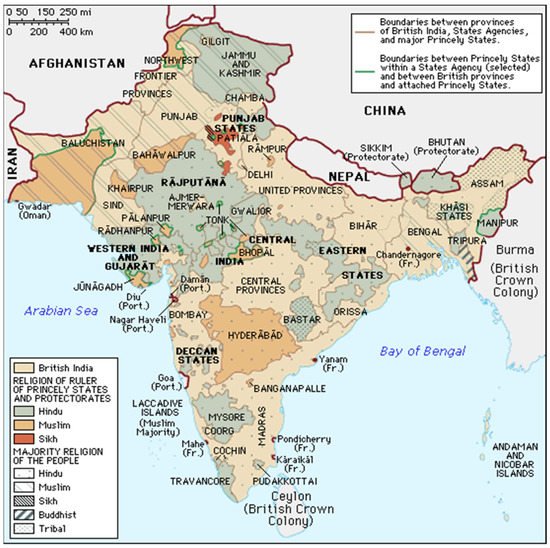

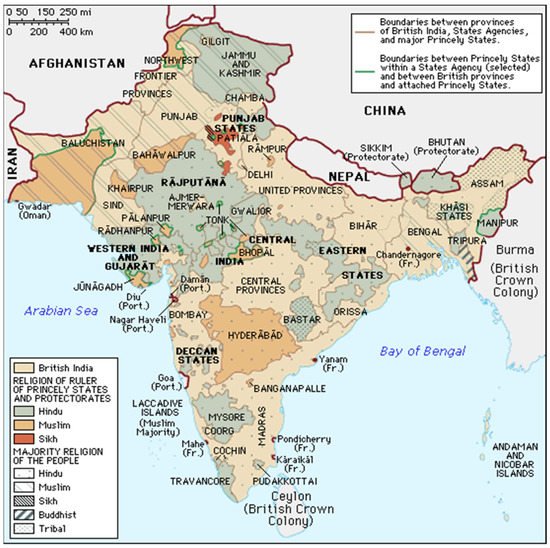

Before the creation of Pakistan in 1947, South Asia was separated into diverse archaeological circles and Pakistan adopted this organizational structure for the management of cultural heritage. West and East Pakistan’s circles were the successor of colonial frontier and eastern circles, respectively, whereas two more circles known as Northern circles with their head offices were located at Lahore and Agra for the management of Hindu, Buddhist, Muslim, and British monuments. Later on, in 1928 and 1931, these central stations were moved to the former frontier circle and in 1946 the administration of those monuments within the Sindh Province was also shifted to the Frontier circle. Figure 2 shows the control of the British Empire on the Indian subcontinents and illustrates a clear understanding of the organizational structure for the management of cultural heritage before 1947 i.e., pre-partition. After the partition and independence of Pakistan, as shown in Figure 3, this circle was re-organized and renamed West Pakistan, and all monuments found therein were set beneath its jurisdiction [3][10][3,12].

The partition map shown in Figure 3, illustrates the two parts of Pakistan, West, and East, separated from each other with India in the center. Since the unfavorable geographical position of East Pakistan to be a part of Pakistan, yielded independence of Bangladesh in 1971, formerly known as East Pakistan, hence, Pakistan was only left with Western Circle. The country was at that point re-organized into Northern circle and Southern circle of archaeology, which favored the efficiency of the Federal Archaeological Department, especially in the field of conservation.

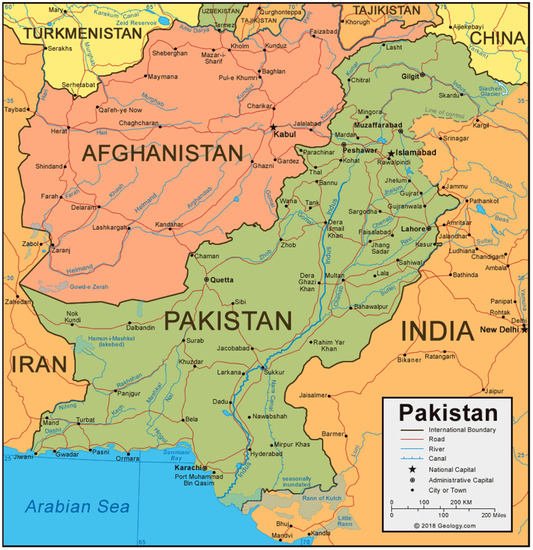

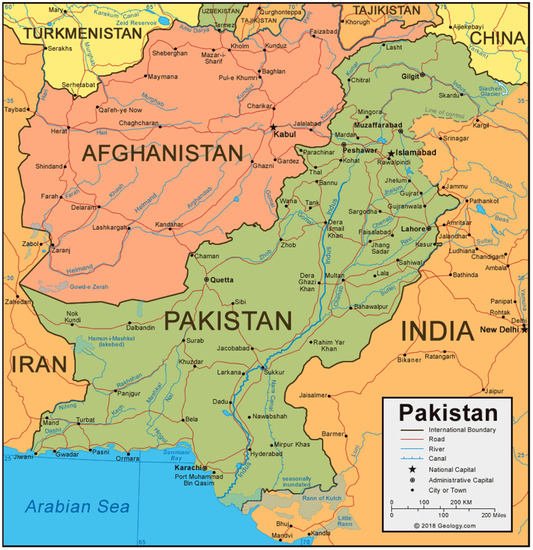

For advance productivity, the Northern circle of archaeology was subdivided into four territorial workplaces at Multan, Taxila, Gilgit, and Peshawar, while the Southern circle of archaeology was subdivided into two territorial workplaces in Quetta and Hyderabad. Yet, regardless of all the division and production of territorial offices, their policy was heavily influenced by the Director-General of Archaeology and Museums, whose office was in Karachi till 1998 and afterward moved to Islamabad. In 2011 an unexpected change occurred in the archaeology history of Pakistan, since the time of Sir John Marshal and Sir Alexander Cunningham: control of the 402 registered protected sites and monuments was physically handed over from the federal government to the respective provinces of Pakistan. Each province such as Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Sindh, Punjab, and Balochistan established their departments of archaeology, where the provincial laws gradually adopted, with some changes, the Antiquities Act 1975 on their list of monuments and sites [3][13][14][15][3,15,16,17]. Figure 4 illustrates the territorial overview of Pakistan and its neighboring countries.

Figure 4. Map of Pakistan and neighboring countries. Source: King, A. & Cole, B. (n.d.), Pakistan Map and Satellite Image: Pakistan Map with Cities, Roads and Rivers. Retrieved 18 March 2022, from Geology.com, Geoscience News and Information: https://geology.com/world/pakistan-satellite-image.shtml (accessed on 8 February 2022).

2.2. Laws of Heritage in Pakistan

As specified above, Pakistan implemented a long tradition/practice of heritage preservation from the British colonial government. The previous legacy enactment, the Ancient Monuments Preservation Act (AMP Act, 1904), was a document resulting from the experience gained in the fields of archaeological survey, conservation, and protection of monuments. According to this Act, all kinds of monuments should be preserved, irrespective of their cultural and religious values [10][13][16][12,15,18].

At Independence, Pakistan adopted the AMP Act 1904 for the preservation and management of monuments and archaeological sites. In 1968, when the Antiquities Act was subjected to minor modifications and changes, a counseling board was formed to advise on all legacy issues and re-defined as “antiquity” all monuments dating earlier than May 1857. It also gave the authority to the federal government’s Department of Archaeology to take the guardianship of monuments in case their security is in threat or if they are on sale or in the absence of their owner. The AMP Act’s twofold “ancient monuments” and “antiquity” were replaced by “moveable” and “immovable” antiquities, with almost complete definitions [13][15].

The current Antiquities Act, passed in 1975 and later amended in 1990, redefined the ancient objects as older than 75 years. It prohibited new construction or excavation around protected monuments within a distance of 200 feet [3]. More regional under practice laws in different provinces include the national fund for Cultural Heritage Act (1994), which allow budgetary and scientific support for the protection and conservation projects, Karachi Building & Town Planning Regulations (2002), Punjab Heritage Foundation Act (2005), and Lahore Walled City Act (2012) [17][19].

Prior to the devolution of the Federal Archaeology Department into the provincial level (18th Constitutional Amendment, 2011), in the province of Punjab, the Punjab Special Premises Act (1985), the Sindh Cultural Heritage (Preservation) Act (1994), and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) Antiquities ordinance (1997) were passed and under practice in the respective provinces [17][19]. Moreover, after the 18th Constitutional Amendment (2011), another major development was the act passed by the Balochistan assembly in 2014. The Antiquities Act (2014) is the first provincial act for Balochistan since the independence of Pakistan [18][20]. Finally, KPK passed a further Antiquities Act (2016) with minor changes with respect to the Antiquities Act of 1975 regarding penalties and defining the threshold of 100 years period to be considered as “antiquity” [17][19]. These provincial laws are based on the Antiquities Act of 1975 (amended in 1990), with some changes that are uniformly applicable on archaeological sites, architectural heritage, and monuments, irrespective of their nature, state, and classification [3][17][18][19][3,19,20,21]. Figure 5 shows the present map of Pakistan with the territories of its provinces with their administrative capitals whereas Table 1 illustrates the major heritage legislations of Pakistan on the national and provincial level since independence, 1947 till the current practice.

Figure 5. Present map of Pakistan with provinces’ boundaries and their administrative capitals detail. Source: King, A. & Cole, B. (n.d.), Pakistan Map and Satellite Image: Pakistan Map with Provinces. Retrieved 18 March 2022, from Geology.com, Geoscience News and Information: https://geology.com/world/pakistan-satellite-image.shtml (accessed on 8 February 2022).

Table 1.

Major heritage legislation of Pakistan on the national and provincial level.

| Year | National Landmarks | Provincial Landmarks |

|---|---|---|

| 1947 | Antiquities Act 1947 (retitled of AMP-1904) | - |

| 1960 | - | Conservation Cell in Punjab |

| 1968 | Antiquities Act 1968 | - |

| 1975 | Antiquities Act 1975 | - |

| 1985 | - | Punjab Special Premises Act |

| 1990 | Major amendment in Antiquities Act 1975 | - |

| 1994 | - | Sindh Cultural Heritage (Preservation) Act |

| 1997 | National Fund for Cultural Heritage Act | North-West Frontier Province (now Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) Antiquities ordinance |

| 2002 | - | Karachi Building & Town Planning Regulations |

| 2005 | - | Punjab Heritage Foundation Act |

| 2011 | Transfer of responsibilities and power from federal to provincial governments | - |

| 2014 | - | Balochistan Antiquities Act 2014 |

| 2016 | - | Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Antiquities Act 2016 |