Adventitious root (AR) formation is required for the vegetative propagation of economically important horticultural crops, such as apples. Asexual propagation is commonly utilized for breeding programs because of its short life cycle, true-to-typeness, and high efficiency. The lack of AR formation from stem segments is a barrier to segment survival.

- apples

- adventitious root (AR)

- formation

- asexual reproduction

- sugars

- polyamines

1. Multiple hHormonal pPathways mMediate aAdventitious rRooting

After separation from the donor plants, stem cuttings critically modify hormone homeostasis in the detached shoots [1]. Different growth regulators were examined to increase the rooting ability of stem cuttings. DuriIng the last few decades, several haveit has been conducted on the formation of ARs in apples. Different endogenous hormones play a key role in forming ARs in apples. Auxin, as a master controller, promotes AR induction and initiation stages while inhibiting the AR emergence stage. Auxin crosstalk with melatonin (MT) also promotes the AR induction stage. Cytokinin (CK) works antagonistically to auxin. Gibberellic acid 3 (GA3) also plays a negative role in the initial stages. Moreover, ethylene (ET) and jasmonic acid (JA) can inhibit the induction stage, and their roles in other stages are unclear. Abscisic acid (ABA) is a negative regulator of AR formation at all stages. The role of various hormones in the multiple phases of AR formation. The details of hormones are explained below.

1.1. Auxin: aA mMaster rRegulator for ARs

Auxin is involved in various physiological events, including vascular differentiation, cell expansion, lateral roots (LRs), and ARs. More auxin is needed to induce ARs, but later, ithis is not necessary for the AR emergence stage [2]. Auxin treatment was shown to boost assimilate translocation from the leaf and sugar content at the root growth site [3]. Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) is perhaps the most prevalent natural auxin, but Indole-3-butyric acid (IBA) is the most frequently utilized exogenous auxin for increasing ARs in most species, particularly in difficult-to-root genotypes. Recently, it was conducted on M 116 apple clonal rootstock to identify the effects of different concentrations of IBA and naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA) (IBA: T1, 1500; T2, 2000; T3, 2500; T4, 3000; T5, 3500; T6, 4000 ppm; NAA: T7, 500; T8, 1000; T9, 1500 ppm) compared with T10, control plants during adventitious rooting under mist chamber conditions. TheIt resultwas suggested that increasing auxin levels correlated positively with rooting success. IBA treatments significantly improved rooting. T5 had the highest rooting percentage (57.12%), AR numbers per cutting (7.33), AR length (34.85 cm), and AR diameter (5.27 mm) when compared to other treatments and control [4]. Furthermore, the Jork9 was also treated with auxins (IAA, IBA, and NAA). The cultures were kept in darkness during the initial time of rooting treatment. During this phase, the AR initials were made, then cultureds were shifted to light. NAA and IAA or IBA treatments obtained the lowest ARs (8) and the highest ARs (15), respectively. The maximal AR numbers were recorded throughout a broad range of IAA levels (10-–100 µM), although at only one level of IBA or NAA (10 µM and 3 µM, respectively) [1]. It was indicated that the duration of exposure to auxins mainly controlled the AR formation. The cuttings are not highly responsive to auxin within the first 24 hours after being collected. It is believed that during this lag time, cells dedifferentiate and become capable of responding to the rhizogenic signal, auxin. The cells that give rise to the AR primordia are often seen between the vascular bundles and store starch over the first 24 hours. The rhizogenic activity of auxin in the induction stage then commits previously activated cells to create AR primordia for up to 72 hours. During this time, auxin pulses stimulate the highest AR numbers. Auxin is no longer necessary after 96 hours, and auxin levels advantageous for establishing root meristemoids are restrictive during this period [5].

IBA promotes AR formation in M.9 and M.26 apple rootstocks, but higher AR formation was seen in M.26, which is due to the high amount of free IAA in the stem basal part compared to M.9. Furthermore, the conjugated IAA level was higher in M.9 as compared to M.26, suggesting that the difference between AR responses in both rootstocks may be associated with free IAA content in stem basal parts [16]. During the whole process of adventitious rooting, endogenous auxin, or applied externally, plays a critical function at each step. In the AR initial phases, a high level of endogenous auxin is generally associated with a high rooting rate [67]. When the auxin is applied exogenously to increase root formation, it influences the endogenous auxin concentration, which generally reaches a maximum after wounding [78]. Still, in some casituationes, the auxin peak was not detected [89]. The endogenous level of auxin induces the AR primordia formation, and the quantity of primordia formation is raised together with the elevation of the IAA level [910]. In apples, IBA was found to be highly important for inducing adventitious rooting in M.26 apple rootstock. The other hormones seem to be indirectly involved in the control of ARs by their interaction with the auxin, where the endogenous level of IAA was observed to be higher at the early stage and induces primordia. Then, the level of IAA decreases towards a later stage [211]. These variations in the IAA levels suggest that auxin plays a critical function at the early stages and may not be crucial after the AR primordia have been established. IBA-treated cuttings of Malus prunifolia var. ringo produced more ARs than cuttings treated with the auxin transport inhibitor NPA, which completely inhibited AR formation. This shows that IBA plays a role in AR formation [1012]. In M9-T337 apple stem cutting, IBA inhibited AR elongation at later stages of development by decreasing cell length and by decreasing the expression of genes related to cell elongation [413]. Moreover, transcriptome sequencing situation s on IBA-treated T337 cuttings showed that auxin, both endogenous and exogenous, regulates AR formation through homologous signaling pathways to some degree. AR formation is largely controlled via the auxin signaling pathway. Furthermore, various hormone, wounding, as well as sugar signaling pathways work together with the auxin signaling pathway to regulate adventitious rooting in T337 [1114]. In M.9 apple rootstock, IAA stimulates the process of AR formation by the upregulation of PIN-FORMED (PIN). Auxin promotes the multiplication and extension of AR founder cells via starch grain hydrolysis, resulting in endomembrane system multiplication, lenticel dehiscence, and AR emergence. This effect was inhibited by the NPA application [1215]. Nevertheless, in stem cuttings of Malus species, the IBA promotes more root formation than the IAA. At the same time, it was changed only at deficient IAA levels, implying that the IBA was operational or controlled IAA activity [1316].

[1417] applied 1 mg/L IBA to different apple rootstocks with different rooting abilities, including MP, SH6, T337, and M.26, to detect the effect of IBA on AR formation compared with control plants. The results showed that MP was easy to root and developed ARs in both groups. However, M.26 produced some ARs in IBA-treated groups. But T337 and SH6 have poorly developed ARs in both groups. Moreover, microRNA160 (miR160) mediates AR formation; therefore, five members of miR160 were found in the apple with two target genes: auxin response factor 16 (ARF16) and ARF17. MiR160 was highly expressed in SH6 and T337 and lower in MP and M.26 in both groups. Following that, miR160a was cloned from M.26 and overexpressed in tobacco plants, causing severe defects in AR formation, which were released by IBA application to transgenic plants

[14]. A comprehensive proteomic analysis was conducted on the role of IBA (1 mg/L) in T337 during AR formation. It was showed that AR rate and length were increased after IBA treatment compared with control cuttings. IBA treatment increases the content of IAA, ABA, and (brassinolide) BR and decreases ZR, GA, and JA content. The expression profiles of differentially expressed proteins were strictly related to phytohormone signaling, protein homeostasis, carbohydrate uptake and energy synthesis, reactive oxygen and nitric oxide signaling, as well as biological processes associated with cell wall remodeling. These are all the most important AR formation processes by IBA application [11].

Concerning auxin signaling pathways, the degrading of AUX/IAA stimulated ARF transcripts, which in turn stimulated the auxin-responsive gene expressions [12]. Numerous genetic investigations have shown the contribution of ARFs in plant developments. In Arabidopsis, ARF7 and ARF19 show specific and dynamic gene expression profiles throughout embryogenesis, seedling development, and rooting [15][13]. Single mutants arf7 and arf19 limit the formation of ARs and LRs, but double mutants are initiated to produce significantly fewer roots [13][16]. They are considered key players in the formation of ARs in apples, where they are more expressed at important time points [17]. Several miRNAs are key players in root growth, including miR160, which is considered necessary for the development of root tips and gravity sensing via the participation of their targets, such as ARF10 and ARF16

[18], which regulate auxin-responsive gene expression through binding with auxin response elements in the promoters. In addition, callus initiation was repressed by miR160 from pericycle-like cells but activated by AFR10

[19]. Furthermore, smaller and gravitropic roots and tumor-like apexes were seen by the over-expression of miR160c

[1820]. This phenotype was related to unrestrained mitosis and a lack of columella cell differentiation in the root apical meristem (RAM) [1821]. A very similar phenomenon was also perceived in double mutants of arf10 and arf16, where miR160 and their target genes might be necessary to limit cell divisions in root tips and stimulate cell extension and differentiation. Moreover, the contribution of miR160 and ARFs in response to auxin signals during AR formation might play a critical role in regulating apple ARs

[20]. In contrast with miR160, miR167, also an auxin-related miRNA whose target genes are ARF6 and ARF8, is an adverse controller for adventitious rooting. Furthermore, ARF8 and ARF17 play opponents in auxin homeostasis in Arabidopsis [21][22].

On the other hand, miR167 in rice seemed to be a key controller of AR formation

[23]. According to Arabidopsis, in which miR390 was regulated by auxin via the roles of ARF2, ARF3, and ARF4, conversely, miR390 expression was restricted by ARF4 at the base of root primordia

[20]. Moreover, AR development was positively regulated by miR390a in apple, which shows its regulatory ability over ARFs. MiR390 and miR160 are important in forming ARs. The ARFs (target genes) also act as a crucial controller in auxin signal transduction during the process of adventitious rooting in apple rootstocks [24]. Auxin-induced adventitious rooting largely depends on miR156 high expressions in Malus xiaojinensis via MxSPL26, independent of PINs and ARFs

[25]. Conversely, it does not affect Eucalyptus grandis

[2624]. So rooting regulated by miR156 might be species-specific. However, miR156 can be an essential factor for AR induction but not a determining element in woody plant species. Moreover, in apple cuttings, wounding is knotty with the induction of adventitious rooting

[24].

The auxin gradient in root tips is maintained by PIN auxin polar transport, which stimulates root growth

[27]. In apples, the PIN family consists of eight members. All were differentially expressed at different stages of AR formation. For example, PIN8 and PIN10 were upregulated and largely associated with the induction stage. Upregulation of all PINs was detected towards the initiation stage, whereas PIN4, PIN5, and PIN8 were all upregulated and largely associated with the emergence stage, suggesting their regulatory roles in adventitious rooting [28]. Furthermore, CK repressed PIN1 expression during adventitious rooting to regulate polar auxin transport

[29]. The AUXIN RESISTANCE1 (AUX1) gene is recognized as an auxin influx carrier

[30]. Besides, the aux1 mutant developed few roots and showed reduced root gravitropism; it reduced IAA accumulation in the roots and acted as an auxin influx transporter to stimulate root growth via allocating IAA among root and shoot organs

[31].

In Arabidopsis, LATERAL ORGAN BOUNDARIES-DOMAIN (LBD) LBD16 and LBD29 are positively controlled by ARF7 and ARF19 and induce rooting

[1632]. Recently, ARF7 and ARF19 stimulate LBD16 and LBD19, which, in turn, activate adventitious rooting in apples

[1726]. The Wuschel-related homeobox gene WOX11 was identified as a key regulator of Arabidopsis root development and apple ARs

[3215]. Short root (SHR) also plays a positive function in forming the LR stem cell niche as well as AR's meristem

[33]. WOX5 stimulates WOX11 to endorse the beginning of root primordia and organogenesis [34], and WOX5 is considered the initial indicator for adventitious rooting

[35]. Furthermore, WOX5, WOX11, and SHR are all auxin-inducible and contribute positively to integrating numerous signals related to root induction

[36]

[3722]. Furthermore, in Arabidopsis, Liu and colleagues found that the auxins induced WOX11 during the initial stage of cell fate transition, and WOX11 increased the transcript of

LBD16 and LBD29 during adventitious rooting

[37]. Subsequently, harmonizing transcript abundance of these genes could promote rooting by stimulating cell cycle-related (CYCD1;1 and CYCP4;1) gene expression in apples [38]

1.2. Cytokinin: aA rRequired iInhibitor

[3945]. Several have linked CK with the inhibition of AR formation

RR1

RR2

RR3

AHK4

PIN1

PIN2

PIN3

AUX1

YUCCA1

YUCCA10

IAA23

ARF6

ARF7

ARF8

ARF19

Malus sieversii Roem

MsGH3.5

GH3.5

GH3.5 transcript via binding to its promoter, connecting auxin and CK signaling. Overexpressed

MsRR1 plants also showed some ARs, consistent with MsRR1a

MsGH3.5

MsGH3.5

[4855]. A previous showed that CK is essential in the initial phase of adventitious rooting in the Jork 9 apple rootstock. Lovastatin and simvastatin are CK-synthesis inhibitors and inhibit AR formation. This negative effect was partially released by adding zeatin, confirming its role in forming ARs. Still, it stimulates cell divisions at low concentrations just after wounding

1.3. Ethylene: aA pPositive or nNegative rRegulator for ARs

ET plays a crucial function in regulating ARs in many species. Many experiments were conducted to identify their roles in root formation. The findings of these experiments were extremely flexible for specific species. ET behaved as activators or inhibitors and did not influence the formation of ARs. Because of earlier findings, auxin affects ET synthesis [4957]. Subsequently, many efforts have been made to identify how auxin interacts with ET during AR formation. High ET level tissues amplified the responsiveness of root developing tissues in response to endogenous IAA. The role of ET was knownstudied in M9-T337 apple stem cutting during AR formation. The AgNO3 (ethylene inhibitor) reduced the appearance of ET and promoted the AR’s emergence and development. However, the ET precursor, 1 aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC), was added to the MS medium, where it may convert into ET, inhibiting AR emergence and decreasing AR length in M9-T337 [413]. Harbage and Stimart [2158] found that ET was not involved in AR formation in apple micro-cuttings of Gala and Triple Red Delicious. This wastudy found that IBA-induced ET formation was reduced by aminoethoxyvinylglycine (AVG), although the AR number continued to be IBA-dependent. ACC restored the inhibitory effect of IBA+AVG on rooting, while ACC separately had little impact on the AR number. Unlike 2,3,5-triiodobenzoic acid (TIBA) and N-1-naphthylphthalamic acid (NPA), which impede polar auxin transport, ET production is increased without increasing the AR number [2158]. ET inhibits or promotes the process of root development depending on the stage of the process. It has a stimulatory role at the initial stage but reflects an inhibitory role at later stages of ARs’ development [505]. Root development can also be inhibited by ET, mainly by limiting cell expansion, but this does not affect root meristem activation [5159].

1.4. Abscisic aAcid: a nA Negative rRegulator for ARs

1.5. Jasmonic aAcid: a pA Positive or nNegative rRegulator for ARs

JA, usually related to mechanical wounding, provides defense against plant pathogens. In the last decade have focused primarily on JA’s role in plant development and exposed JA as a critical hormone. It participates in different developmental mechanisms: hypocotyl elongation, primary root (PR) elongation, LR and AR formation, and flower development

1.6. Melatonin: aA pPositive rRegulator

MT is thought to be necessary for the creation and growth of ARs in apples. [2437]. In plants, MT served as a vital regulatory signal [6677] and was essential for root formation, stress response, explants, and shoots [6778][6879][6980]. It has indicated that the exogenous treatment of MT stimulated AR formation in cuttings of Malus prunifolia, where MT mainly affects the AR induction stage by IAA homeostasis. WOX11 was induced by MT, and apple plants overexpressing MdWOX11 developed more ARs than the GL-3 WT plant, suggesting that MdWOX11 promotes ARs by MT signaling [2437]. A few studies have advocated that exogenous MT at low concentrations could increase the endogenous content of IAA, and it is supposed that this stimulating MT effect on growth and development might be triggered by this rise in IAA levels [7081]. On the other hand, another one study has suggested that the effect of MT on root formation and differentiation is IAA independent [7182]. The IAA content was increased at the AR induction stage after the application of MT; however, it was reduced at the AR initiation stage and emergence stage in apple [2437].

1.7. Gibberellic acid and brassinosteroids: a positive or negative regulator for ARs

The specific roles of GA and BR are still largely unknown in the regulation of ARs. The effect of GA3 was knownstudied in M9 cv. Jork stem discs. First, the discs were cultured in darkness for 24 h on a root-inducing medium containing 24.6 μM IBA. Afterward, the discs were shifted to light exposure and cultured on a hormone-free medium and a medium containing 10 μM GA3 for different timepoints of adventitious rooting. The results suggest that GA3 treatments limit AR formation from the initial to final stages of AR formation [2583]. Moreover, the concentration of GA3 was significantly increased at the initiation of ARs, indicating that GA3 plays an important role in forming apple ARs [1012]. However, some shreds of evidence show that BR participated in AR formation. The availability of BRs triggers dual effects on the formation of ARs: the enhancing effect at low levels and the inhibitory effect at high levels [7284]. Their high concentration inhibited AR formation in apple rootstock [1012]. However, the above information is not enough to identify the specific role of GA and BR in forming ARs.

2. Role of Phenolic Compound in the Regulation of ARs

3. Role of Sugars in the Regulation of ARs

4. Role of Polyamines in the Regulation of ARs

5. Role of Nutrients in the Life of ARs

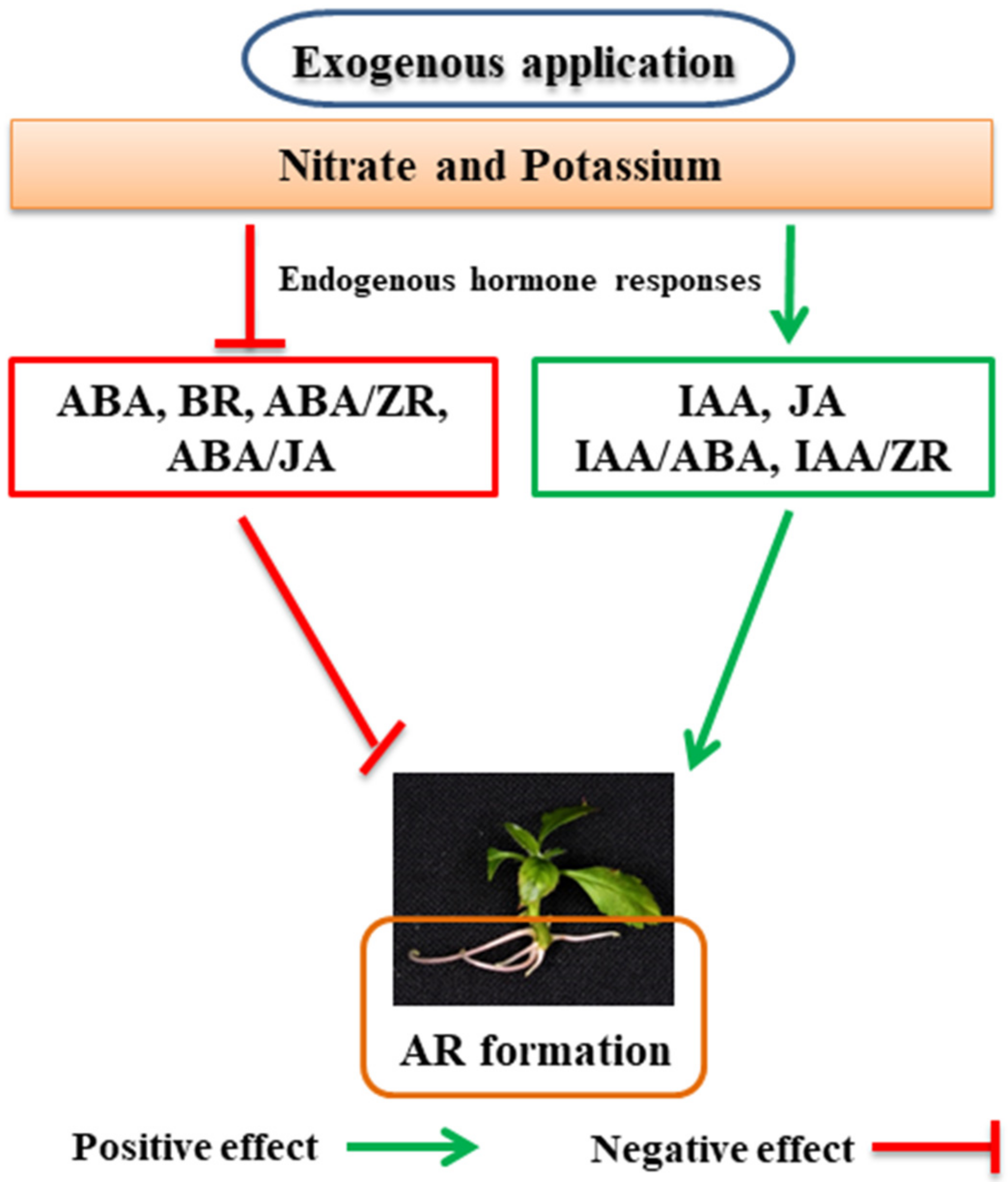

5.1. Role of Nitrogen in the Formation of ARs

5.2. Role of Potassium in the Formation of ARs