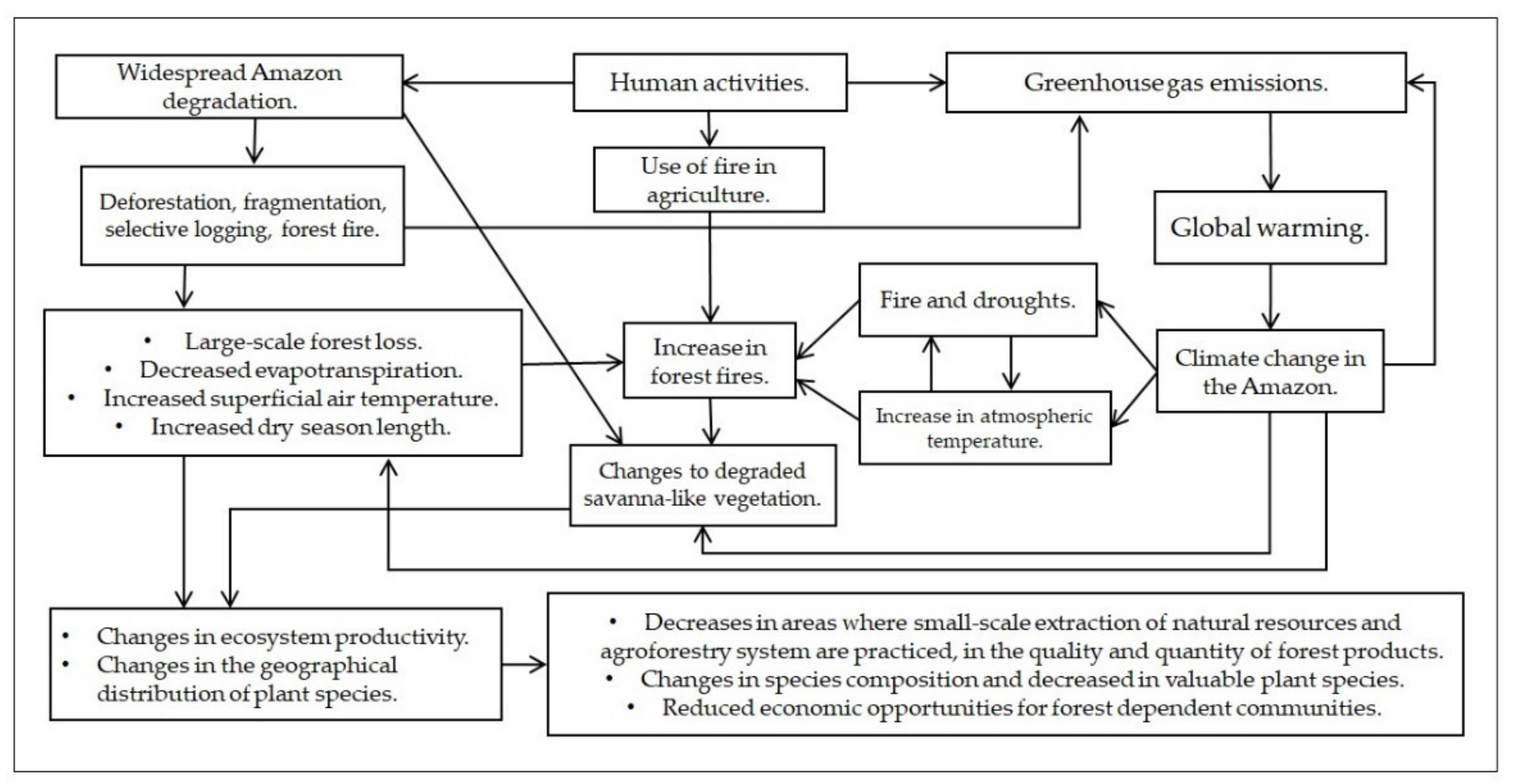

Environmental changes caused by human activities alter the water, energy, and carbon cycles in the Amazon region. This has resulted in biological changes across several plant species, some of which are used in both regional and global trade and represent important sources of food and income for people. Reports from local people and scientific studies point to the effects of deforestation, forest degradation, and climate change on native plant species. Indeed, people who are typically dependent on natural resources and ecosystem services are the most threatened by plant species productivity and geographical distribution changes. However, there is a lack of scientific literature concerning the effects of environmental changes on plant species and forest-dependent communities in the Amazon region.

- agroforestry system

- climate change

- deforestation

- forest degradation

- non-timber forest products

1. Introduction

2. Current Insights

2.1. Deforestation and Forest Degradation Implications to Forest Dependent Communities

2.2. The Effects of Climate Change on Plant Species

| Botanical Family | Species Name | Scientific References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annonaceae | Guatteria punctata | (Aubl.) R.A.Howard | [98] | [46] |

| Arecaceae | Attalea speciosa | Mart. ex Spreng. | [46] | [47] |

| Cannabaceae | Trema micrantha | (L.) Blume | [97] | [48] |

| Dilleniaceae | Curatella americana | L. | [46] | [47] |

| Euphobiaceae | Croton diasii | Pires ex Secco & P.E.Berry | [97] | [48] |

| Euphobiaceae | Crotonmatourensis | Aubl. | [98] | [46] |

| Euphorbiaceae | Sapium marmieri | Huber | [46] | [47] |

| Fabaceae | Apuleia leiocarpa | (Vogel) J.F.Macbr. | [46] | [47] |

| Fabaceae | Inga thibaudiana | DC. | [98] | [46] |

| Hypericaceae | Vismia amazonica | Ewan | [34] | [44] |

| Hypericaceae | Vismia bemerguii | M.E.Berg | [34] | [44] |

| Hypericaceae | Vismia cauliflora | A.C.Sm. | [34] | [44] |

| Hypericaceae | Vismia cayennensis | (Jacq.) Pers. | [34] | [44] |

| Hypericaceae | Vismia guianensis | (Aubl.) Choisy | [34] | [44] |

| Hypericaceae | Vismia japurensis | Reichardt | [34] | [44] |

| Malpighiaceae | Byrsonima duckeana | W.R.Anderson | [98] | [46] |

| Malpighiaceae | Byrsonima stipulacea | A.Juss. | [34] | [44] |

| Malvaceae | Eriotheca longipedicellata | (Ducke) A.Robyns | [97] | [48] |

| Melastomataceae | Bellucia grossularioides | (L.) Triana | [98] | [46] |

| Melastomataceae | Bellucia imperialis | Saldanha & Cogn. | [98] | [46] |

| Rubiaceae | Coutarea hexandra | (Jacq.) K.Schum. | [46] | [47] |

| Rutaceae | Zanthoxylum rhoifolium | Lam. | [97] | [48] |

| Salicaceae | Banara guianensis | Aubl. | [97] | [48] |

| Salicaceae | Caseariadecandra | Jacq. | [97] | [48] |

| Salicaceae | Casearia sylvestris | Sw. | [46] | [47] |

| Solanaceae | Solanum crinitum | Lam. | [97] | [48] |

| Urticaceae | Cecropia purpurascens | C.C.Berg | [34] | [44] |

| Urticaceae | Cecropia sciadophylla | Mart. | [98] | [46] |

| Urticaceae | Pourouma apiculata | Spruce ex Benoist | [98] | [46] |

| Vochysiaceae | Erisma uncinatum | Warm. | [46] | [47] |

2.3. Potential Reduction of Native Amazonian Plants and Annual Range of Economic Losses

2.4. Potential for the Improvement of Agroforestry Systems Strategies and Advancement of Stakeholder Engagement Approaches

References

- Esquivel-Muelbert, A.; Baker, T.R.; Dexter, K.G.; Lewis, S.L.; Brienen, R.J.W.; Feldpausch, T.R.; Lloyd, J.; Monteagudo-Mendoza, A.; Arroyo, L.; Álvarez-Dávila, E.; et al. Compositional response of Amazon forests to climate change. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2019, 25, 39–56.

- Hawes, J.E.; Vieira, I.C.G.; Magnago, L.F.S.; Berenguer, E.; Ferreira, J.; Aragão, L.E.O.C.; Cardoso, A.; Lees, A.C.; Lennox, G.D.; Tobias, J.A.; et al. A large-scale assessment of plant dispersal mode and seed traits across human-modified Amazonian forests. J. Ecol. 2020, 108, 1373–1385.

- Jimenez, J.C.; Marengo, J.A.; Alves, L.M.; Sulca, J.C.; Takahashi, K.; Ferrett, S.; Collins, M. The role of ENSO flavours and TNA on recent droughts over Amazon forests and the Northeast Brazil region. Int. J. Climatol. 2021, 41, 3761–3780.

- Aragão, L.E.O.C.; Anderson, L.O.; Fonseca, M.G.; Rosan, T.M.; Vedovato, L.B.; Wagner, F.H.; Silva, C.V.J.; Silva Junior, C.H.L.; Arai, E.; Aguiar, A.P.; et al. 21st Century drought-related fires counteract the decline of Amazon deforestation carbon emissions. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 536.

- Fontes, C.G.; Dawson, T.E.; Jardine, K.; McDowell, N.; Gimenez, B.O.; Anderegg, L.; Negrón-Juárez, R.; Higuchi, N.; Fine, P.V.A.; Araújo, A.C.; et al. Dry and hot: The hydraulic consequences of a climate change–type drought for Amazonian trees. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2018, 373, 20180209.

- Smith, M.N.; Taylor, T.C.; van Haren, J.; Rosolem, R.; Restrepo-Coupe, N.; Adams, J.; Wu, J.; Oliveira, R.C.; Silva, R.; Araujo, A.C.; et al. Empirical evidence for resilience of tropical forest photosynthesis in a warmer world. Nat. Plants 2020, 6, 1225–1230.

- Berenguer, E.; Lennox, G.D.; Ferreira, J.; Malhi, Y.; Aragão, L.E.O.C.; Barreto, J.R.; Espírito-Santo, F.D.B.; Figueiredo, A.E.S.; França, F.; Gardner, T.A.; et al. Tracking the impacts of El Niño drought and fire in human-modified Amazonian forests. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2019377118.

- IPCC. Summary for Policymakers. In Global Warming of 1.5 °C; An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5 °C above Pre-Industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the Context of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty; Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D., Skea, J., Shukla, P.R., Pirani, A., Moufouma-Okia, W., Péan, C., Pidcock, R., et al., Eds.; World Meteorological Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; 32p.

- Evangelista-Vale, J.C.; Weihs, M.; José-Silva, L.; Arruda, R.; Sander, N.L.; Gomides, S.C.; Machado, T.M.; Pires-Oliveira, J.C.; Barros-Rosa, L.; Castuera-Oliveira, L.; et al. Climate change may affect the future of extractivism in the Brazilian Amazon. Biol. Conserv. 2021, 257, 109093.

- Brandão, D.O.; Barata, L.E.S.; Nobre, I.; Nobre, C.A. The effects of Amazon deforestation on non-timber forest products. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2021, 21, 122.

- ter Steege, H.; Pitman, N.C.A.; Killeen, T.J.; Laurance, W.F.; Peres, C.A.; Guevara, J.E.; Salomão, R.P.; Castilho, C.V.; Amaral, I.L.; de Almeida Matos, F.D.; et al. Estimating the global conservation status of more than 15,000 Amazonian tree species. Sci. Adv. 2015, 1, e1500936.

- Nobre, C.A.; Sampaio, G.; Borma, L.S.; Castilla-Rubio, J.C.; Silva, J.S.; Cardoso, M. Land-use and climate change risks in the Amazon and the need of a novel sustainable development paradigm. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 10759–10768.

- Shanley, P.; Pierce, A.R.; Laird, S.A.; Binnqüist, C.L.; Guariguata, M.R. From Lifelines to Livelihoods: Non-timber Forest Products into the Twenty-First Century. In Tropical Forestry Handbook; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 1–50.

- Lima, M.; Vale, J.C.E.; Costa, G.M.; Santos, R.C.; Correia Filho, W.L.F.; Gois, G.; Oliveira-Junior, J.F.; Teodoro, P.E.; Rossi, F.S.; Silva Junior, C.A. The forests in the indigenous lands in Brazil in peril. Land Use Policy 2020, 90, 104258.

- INPE. Taxas de Desmatamento Amazonia Legal Estados. Available online: http://terrabrasilis.dpi.inpe.br/app/dashboard/deforestation/biomes/legal_amazon/rates (accessed on 1 February 2020).

- Saatchi, S.; Houghton, R.A.; Santos Alvalá, R.C.; Soares, J.V.; Yu, Y. Distribution of aboveground live biomass in the Amazon basin. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2007, 13, 816–837.

- Meza-Elizalde, M.C.; Armenteras-Pascual, D. Edge influence on the microclimate and vegetation of fragments of a north Amazonian forest. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 498, 119546.

- Laurance, W.F.; Curran, T.J. Impacts of wind disturbance on fragmented tropical forests: A review and synthesis. Austral Ecol. 2008, 33, 399–408.

- Fearnside, P.M. Deforestation in Brazilian Amazonia: History, Rates, and Consequences. Conserv. Biol. 2005, 19, 680–688.

- Hooper, E.R.; Ashton, M.S. Fragmentation reduces community-wide taxonomic and functional diversity of dispersed tree seeds in the Central Amazon. Ecol. Appl. 2020, 30, e02093.

- Benchimol, M.; Peres, C.A. Edge-mediated compositional and functional decay of tree assemblages in Amazonian forest islands after 26 years of isolation. J. Ecol. 2015, 103, 408–420.

- Carneiro, M.S. Da certificação para as concessões florestais: Organizações não governamentais, empresas e a construção de um novo quadro institucional para o desenvolvimento da exploração florestal na Amazônia brasileira. Bol. Mus. Para. Emílio Goeldi. Ciênc. Hum. 2011, 6, 525–541.

- Presidência da República. Brazil Gestão de Florestas Públicas Para a Produção (Lei N 11.284); Casa Civil: Brasilia, Brazil, 2006.

- Rist, L.; Shanley, P.; Sunderland, T.; Sheil, D.; Ndoye, O.; Liswanti, N.; Tieguhong, J. The impacts of selective logging on non-timber forest products of livelihood importance. For. Ecol. Manag. 2012, 268, 57–69.

- Berenguer, E.; Ferreira, J.; Gardner, T.A.; Aragão, L.E.O.C.; Camargo, P.B.; Cerri, C.E.; Durigan, M.; Oliveira, R.C.; Vieira, I.C.G.; Barlow, J. A large-scale field assessment of carbon stocks in human-modified tropical forests. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2014, 20, 3713–3726.

- Martini, A.M.Z.; Rosa, N.A.; Uhl, C. An Attempt to predict which Amazonian tree species may be threatened by logging activities. Environ. Conserv. 1994, 21, 152–162.

- Richardson, V.A.; Peres, C.A. Temporal Decay in Timber Species Composition and Value in Amazonian Logging Concessions. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159035.

- Fearnside, P.M. Biodiversity as an environmental service in Brazil’s Amazonian forests: Risks, value and conservation. Environ. Conserv. 1999, 26, 305–321.

- Shanley, P.; Luz, L. The Impacts of Forest Degradation on Medicinal Plant Use and Implications for Health Care in Eastern Amazonia. Bioscience 2003, 53, 573–584.

- Guariguata, M.R.; Licona, J.C.; Mostacedo, B.; Cronkleton, P. Damage to Brazil nut trees (Bertholletia excelsa) during selective timber harvesting in Northern Bolivia. For. Ecol. Manag. 2009, 258, 788–793.

- Osborne, T.; Kiker, C. Carbon offsets as an economic alternative to large-scale logging: A case study in Guyana. Ecol. Econ. 2005, 52, 481–496.

- Scoles, R.; Canto, M.S.; Almeida, R.G.; Vieira, D.P. Sobrevivência e Frutificação de Bertholletia excelsa Bonpl. em Áreas Desmatadas em Oriximiná, Pará. Floresta Ambient. 2016, 23, 555–564.

- Michaletz, S.T.; Johnson, E.A. How forest fires kill trees: A review of the fundamental biophysical processes. Scand. J. For. Res. 2007, 22, 500–515.

- Shanley, P.; Luz, L.; Swingland, I.R. The faint promise of a distant market: A survey of Belém’s trade in non-timber forest products. Biodivers. Conserv. 2002, 11, 615–636.

- Davidson, E.A.; Araújo, A.C.; Artaxo, P.; Balch, J.K.; Brown, I.F.; Mercedes, M.M.; Coe, M.T.; Defries, R.S.; Keller, M.; Longo, M.; et al. The Amazon basin in transition. Nature 2012, 481, 321–328.

- Barlow, J.; Peres, C.A. Fire-mediated dieback and compositional cascade in an Amazonian forest. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2008, 363, 1787–1794.

- Meir, P.; Brando, P.M.; Nepstad, D.; Vasconcelos, S.; Costa, A.C.L.; Davidson, E.; Almeida, S.; Fisher, R.A.; Sotta, E.D.; Zarin, D.; et al. The effects of drought on Amazonian rain forests. Geophys. Monogr. Ser. 2009, 186, 429–449.

- Brando, P.; Macedo, M.; Silvério, D.; Rattis, L.; Paolucci, L.; Alencar, A.; Coe, M.; Amorim, C. Amazon wildfires: Scenes from a foreseeable disaster. Flora 2020, 268, 151609.

- De Faria, B.L.; Brando, P.M.; Macedo, M.N.; Panday, P.K.; Soares-Filho, B.S.; Coe, M.T. Current and future patterns of fire-induced forest degradation in Amazonia. Environ. Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 095005.

- Le Page, Y.; Morton, D.; Hartin, C.; Bond-Lamberty, B.; Pereira, J.M.C.; Hurtt, G.; Asrar, G. Synergy between land use and climate change increases future fire risk in Amazon forests. Earth Syst. Dyn. 2017, 8, 1237–1246.

- Aleixo, I.; Norris, D.; Hemerik, L.; Barbosa, A.; Prata, E.; Costa, F.; Poorter, L. Amazonian rainforest tree mortality driven by climate and functional traits. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2019, 9, 384–388.

- Borma, L.S.; Nobre, C.A. Secas na Amazônia: Causas e Consequências; Oficina de Texto: São Paulo, Brazil, 2013; p. 367.

- Brando, P.M.; Balch, J.K.; Nepstad, D.C.; Morton, D.C.; Putz, F.E.; Coe, M.T.; Silvério, D.; Macedo, M.N.; Davidson, E.A.; Nóbrega, C.C.; et al. Abrupt increases in Amazonian tree mortality due to drought-fire interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 6347–6352.

- Mesquita, R.D.C.G.; Massoca, P.E.D.S.; Jakovac, C.C.; Bentos, T.V.; Williamson, G.B. Amazon Rain Forest Succession: Stochasticity or Land-Use Legacy? Bioscience 2015, 65, 849–861.

- Uhl, C.; Kauffman, J.B. Deforestation, Fire Susceptibility, and Potential Tree Responses to Fire in the Eastern Amazon. Ecology 1990, 71, 437–449.

- Longworth, J.B.; Mesquita, R.C.; Bentos, T.V.; Moreira, M.P.; Massoca, P.E.; Williamson, G.B. Shifts in Dominance and Species Assemblages over Two Decades in Alternative Successions in Central Amazonia. Biotropica 2014, 46, 529–537.

- Feigl, B.; Cerri, C.; Piccolo, M.; Noronha, N.; Augusti, K.; Melillo, J.; Eschenbrenner, V.; Melo, L. Biological Survey of a Low-Productivity Pasture in Rondônia State, Brazil. Outlook Agric. 2006, 35, 199–208.

- Uhl, C.; Buschbacher, R.; Serrao, E.A.S. Abandoned Pastures in Eastern Amazonia. I. Patterns of Plant Succession. J. Ecol. 1988, 76, 663.

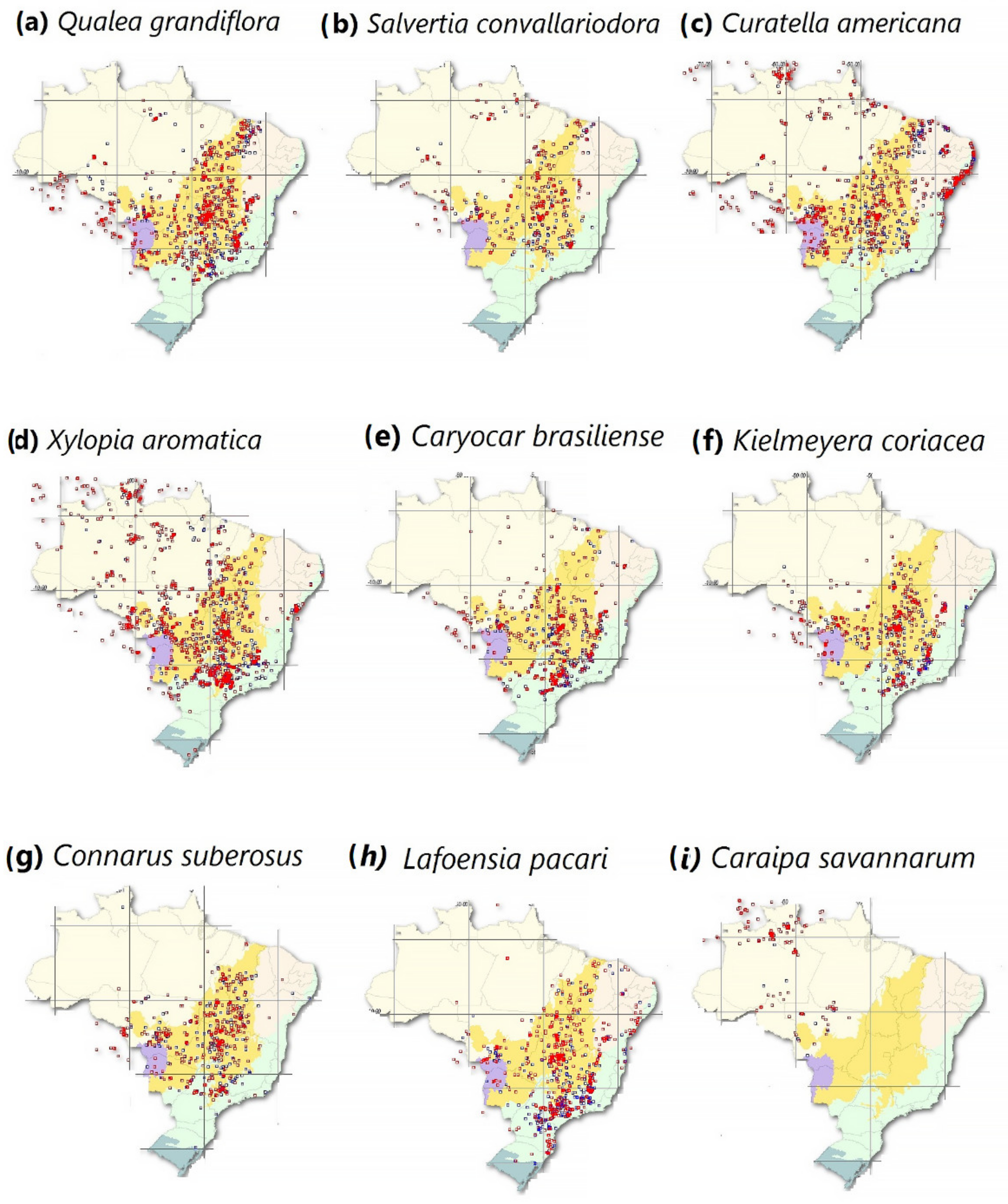

- Gomes, V.H.F.; Vieira, I.C.G.; Salomão, R.P.; ter Steege, H. Amazonian tree species threatened by deforestation and climate chance. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2019, 9, 547–553.

- López, J.; Way, D.A.; Sadok, W. Systemic effects of rising atmospheric vapor pressure deficit on plant physiology and productivity. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2021, 27, 1704–1720.

- Sales, L.P.; Rodrigues, L.; Masiero, R. Climate change drives spatial mismatch and threatens the biotic interactions of the Brazil nut. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2021, 30, 117–127.

- Miranda, I.S.; Almeida, S.S.; Dantas, P.J. Florística e estrutura de comunidades arbóreas em cerrados de Rondônia, Brasil. Acta Amaz. 2006, 36, 419–430.

- Nobre, C.A.; Sellers, P.J.; Shukla, J. Amazonian Deforestation and Regional Climate Change. J. Clim. 1991, 4, 957–988.

- Oyama, M.D.; Nobre, C.A. A new climate-vegetation equilibrium state for Tropical South America. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2003, 30, 23.

- Salazar, L.F.; Nobre, C.A.; Oyama, M.D. Climate change consequences on the biome distribution in tropical South America. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2007, 34.

- Arruda, D.M.; Fernandes-Filho, E.I.; Solar, R.R.C.; Schaefer, C.E.G.R. Combining climatic and soil properties better predicts covers of Brazilian biomes. Sci. Nat. 2017, 104, 32.

- SpeciesLink Network. The Geographical Distribution of Typical Savannah Species That Are Found in the Brazilian Amazon. Available online: https://specieslink.net/search/ (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Herraiz, A.D.; de Alencastro Graça, P.M.L.; Fearnside, P.M. Amazonian flood impacts on managed Brazilnut stands along Brazil’s Madeira River: A sustainable forest management system threatened by climate change. For. Ecol. Manag. 2017, 406, 46–52.

- Morris, R.J. Anthropogenic impacts on tropical forest biodiversity: A network structure and ecosystem functioning perspective. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2010, 365, 3709–3718.

- Sales, L.; Culot, L.; Pires, M.M. Climate niche mismatch and the collapse of primate seed dispersal services in the Amazon. Biol. Conserv. 2020, 247, 108628.

- Antunes, A.; Simmons, C.S.; Veiga, J.P. Non-timber forest products and the cosmetic industry: An econometric assessment of contributions to income in the Brazilian Amazon. Land 2021, 10, 588.

- IBGE. Produção Agrícola Municipal: Culturas Temporárias e Permanentes (PAM); Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2019; Volume 66.

- Lopes, E.; Soares-Filho, B.; Souza, F.; Rajão, R.; Merry, F.; Carvalho Ribeiro, S. Mapping the socio-ecology of Non Timber Forest Products (NTFP) extraction in the Brazilian Amazon: The case of açaí (Euterpe precatoria Mart) in Acre. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 188, 110–117.

- Castilho, C.V.; Magnusson, W.E.; Araújo, R.N.O.; Luizão, R.C.C.; Luizão, F.J.; Lima, A.P.; Higuchi, N. Variation in aboveground tree live biomass in a central Amazonian Forest: Effects of soil and topography. For. Ecol. Manag. 2006, 234, 85–96.

- Sousa, T.R.; Schietti, J.; Souza, F.C.; Esquivel-Muelbert, A.; Ribeiro, I.O.; Emílio, T.; Pequeno, P.A.C.L.; Phillips, O.; Costa, F.R.C. Palms and trees resist extreme drought in Amazon forests with shallow water tables. J. Ecol. 2020, 108, 2070–2082.

- Vieira, I.; Toledo, P.; Silva, J.; Higuchi, H. Deforestation and threats to the biodiversity of Amazonia. Braz. J. Biol. 2008, 68, 949–956.

- Homma, A.K.O.; Carvalho, R.A.; Ferreira, C.A.P.; Júnior, J.D.B.N. A Destruição de Recursos Naturais: O Caso da Castanha-do-Pará No Sudeste Paraense; Embrapa Amazônia Oriental: Belém, Brazil, 2000.

- IBGE. Produção da Extração Vegetal e da Silvicultura (PEVS); Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2019; pp. 1–16.

- Costa, F.A.; Ciasca, B.S.; Castro, E.C.C.; Barreiros, R.M.M.; Folhes, R.T.; Bergamini, L.L.; Solyno Sobrinho, S.A.; Cruz, A.; Costa, J.A.; Simões, J.; et al. Bioeconomia da Sociobiodiversidade no Estado do Pará, 1st ed.; The Nature Conservancy (TNC Brasil), Banco Interamericano de Desenvolvimento (BID), Natura: Brasilia, Brazil, 2021; pp. 1–37.

- Peters, C.M.; Gentry, A.H.; Mendelsohn, R.O. Valuation of an Amazonian rainforest. Nature 1989, 339, 655–656.

- Groot, R.; Brander, L.; van der Ploeg, S.; Costanza, R.; Bernard, F.; Braat, L.; Christie, M.; Crossman, N.; Ghermandi, A.; Hein, L.; et al. Global estimates of the value of ecosystems and their services in monetary units. Ecosyst. Serv. 2012, 1, 50–61.

- Mataveli, G.A.V.; Oliveira, G.; Seixas, H.T.; Pereira, G.; Stark, S.C.; Gatti, L.V.; Basso, L.S.; Tejada, G.; Cassol, H.L.G.; Anderson, L.O.; et al. Relationship between Biomass Burning Emissions and Deforestation in Amazonia over the Last Two Decades. Forests 2021, 12, 1217.

- Oliveira, M.S.L.; Scaramussa, P.H.M.; Santos, A.R.S.; Benjamin, A.M.S. Análise do custo econômico de um sistema agroflorestal na comunidade Nova Betel, município de Tomé-Açu, estado do Pará. In Proceedings of the II Congresso Internacional das Ciências Agrárias, Teresina, Brazil, 19 December 2017.

- Castro, F.; Futemma, C. Farm Knowledge Co-Production at an Old Amazonian Frontier: Case of the Agroforestry System in Tomé-Açu, Brazil. Rural Landsc. Soc. Environ. Hist. 2021, 8, 3.

- Matos Filho, J.R.; Moraes, L.L.C.; Freitas, J.L.; Cruz Junior, F.O.; Santos, A.C. Quintais agroflorestais em uma comunidade rural no vale do Rio Araguari, Amazônia Oriental. Rev. Ibero-Am. Ciênc. Ambient. 2021, 12, 47–62.

- Gasparinetti, P.; Brandão, D.O.; Araújo, V.; Araújo, N. Economic Feasibility Study for Forest Landscape Restoration Banking Models: Cases from Southern Amazonas State, 1st ed.; Conservation Strategy Fund: Brasilia, Brazil, 2019; pp. 1–49.

- WWF-Brasil. Avaliação Financeira da Restauração Florestal com Agroflorestas na Amazônia, 1st ed.; WWW-Brasil: Brasilia, Brazil, 2020; pp. 1–31.

- Bolfe, E.L.; Ferreira, M.C.; Batistella, M. Biomassa Epígea e Estoque de Carbono de Agroflorestas em Tomé-Açu, PA. Rev. Bras. Agroecol. 2009, 4, 2171–2175.

- Villa, P.M.; Martins, S.V.; Oliveira Neto, S.N.; Rodrigues, A.C.; Hernández, E.P.; Kim, D.G. Policy forum: Shifting cultivation and agroforestry in the Amazon: Premises for REDD+. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 118, 102217.

- Barata, L.E.S. A economia verde: Amazônia. Cienc. Cult. 2012, 64, 31–35.

- BNDES. Fundo Amazônia—Relatórios Anuais (2010–2019); Banco Nacional de Desenvolvimento Econômico e Social: Brasilia, Brazil, 2019.

- Homma, A.K.O.; Menezes, A.J.E.A.; Maués, M.M. Brazil nut tree: The challenges of extractivism for agricultural plantations. Bol. Mus. Para. Emílio Goeldi. Ciênc. Nat. 2014, 9, 293–306.

- Nobre, I.; Nobre, C.A. The Amazonia third way initiative: The role of technology to unveil the potential of a novel tropical biodiversity-based economy. In Land Use—Assessing the Past, Envisioning the Future; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2018; Volume 1, pp. 1–32.

- Nobre, I.; Margit, A.; Nobre, C.A.; Weser-Koch, M.; Veríssimo, A.; Neto, A.F. Amazon Creative Labs of the Cupuaçu-Cocoa Chain; Banco Interamericano de Desenvolvimento: São Paulo, Brazil, 2021; Volume 2.01, p. 116.

- U.S. Embassy & Consulates in Brazil. United States and Brazil to Partner in Biodiversity-Focused Impact Investment Fund for the Brazilian Amazon. Available online: https://br.usembassy.gov/united-states-and-brazil-to-partner-in-biodiversity-focused-impact-investment-fund-for-the-brazilian-amazon/ (accessed on 25 March 2019).