You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Nora Tang and Version 1 by Ahmad Khusairi Azemi.

Medicinal plants may act as an alternative resource or adjunctive treatment option in the treatment of diabetes and its cardiovascular complications. Parkia speciosa (Fabaceae) is a plant found abundantly in the Southeast Asian region. Extracts of P. speciosa, particularly from its seeds and empty pods, show the presence of polyphenols. They also exhibit potent antioxidant, hypoglycemic, anti-inflammatory, and antihypertensive properties. Its hypoglycemic properties are reported to be associated with the presence of β-sitosterol, stigmasterol, and stigmat-4-en-3-one.

- diabetes

- hypoglycemic

- antioxidant

- anti-inflammatory

1. Taxonomical Classification

Kingdom: Plantae; Phylum: Trcheophyta; Class: Magnoliopsida; Order: Fabales; Family: Fabaceae; Genus: Parkia; Species: P. speciosa.

2. Botanical Description

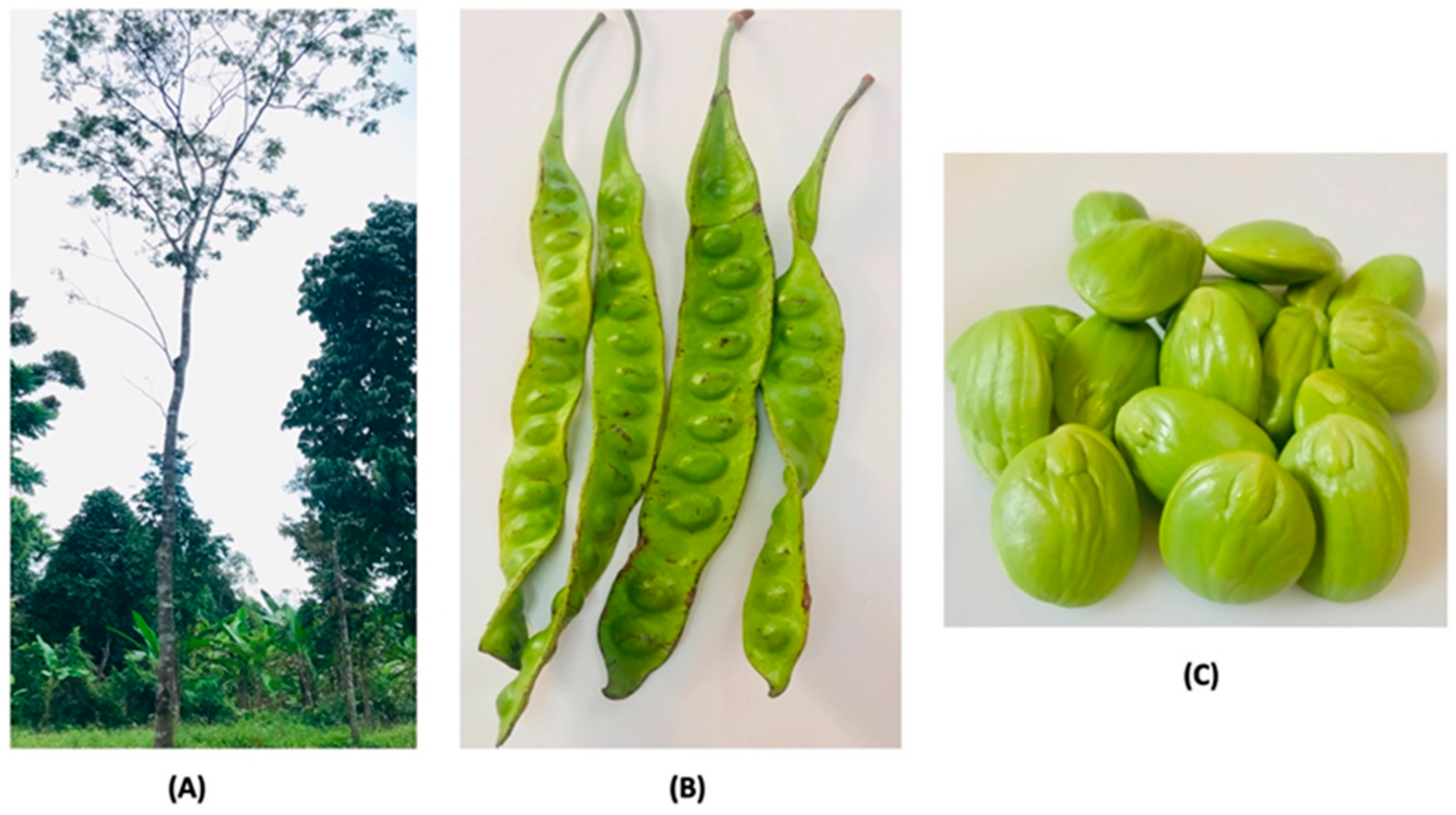

P. speciosa thrives on podzolic sandy loam and in areas near riverbanks in primary lowland rainforests in Southeast Asia. The optimum annual temperature for the proliferation of the plant is 24 °C. The tree is cultivated in the plains up to an elevation of 1500 m. The plant is propagated via seed sowing, stem cutting, and budding [1][2]. The agronomic practices used for the pretreatment of seeds to overcome dormancy and accelerate seed germination are seed coat shelling or soaking of the seeds in water, ample light, and space provision [2]. Seeds are cut opposite to the micropyle to prevent damage to the embryo during seed coat cutting. One year after sowing, at a height of 0.5–1.0 m tall, the trees are transplanted to the field with a distance of 10 m between rows and 10 m between the plants (10 m × 10 m) [2]. The mature plant can grow up to 40 m in height and 1 m in stem circumference (Figure 1a). Its leaves are bipinnate and alternate. It is an ornamental, perennial, and fruit-bearing tree which starts to flower and produce fruit at the age of seven years. It usually flowers in January to March and inAugust to October each year. The flowers are bulb-shaped and droop at the stalk ends, while the fruits are green, flat, and oblong pods of 35–55 cm in length and 3–5 cm in width, beetling in bunches of 6–10 (Figure 1b,c). The seeds have a foul, peculiar, unique, and distinctive smell with an elliptical shape, and can be eaten raw, roasted, cooked, or blanched [3][4]. The seed has a unique taste similar to that of garlic; it has no burning spiciness or pungency, and also has a unique Shiitake-mushroom-like flavor [5]. P. speciosa has been reported to have bioactive compounds, particularly thiazoline-4-carboxylic acid, also known as thioroline, which is an amino acid that gives P. speciosa seed its sulfur smell [6][7].

Figure 1. The tree (A), pods (B), and seeds (C) of P. speciosa plants.

3. Traditional Medicinal Uses of P. speciosa

P. speciosa is a valuable herbal plant consumed by the Southeast Asian communities as a cooking ingredient and for various medicinal purposes. In Malaysia, its’ seeds have always been a popular ingredient in cooking, where they are usually served with chili paste or “sambal”, dried shrimp, and chili pepper as a popular local delicacy. It can be cooked in chili paste mixed with seafood, boiled in coconut milk with a variety of vegetables, or added as an ingredient to many other dishes, including fried rice or stir-fried food [3][2]. It is traditionally used in several ways for the treatment of diabetes and hypertension [8][9][10][11]. It was reported previously that the P. speciosa seeds, pods, and roots were traditionally applied by indigenous communities in Peninsular Malaysia to treat diabetes and hypertension [11]. Furthermore, P. speciosa has also been consumed for the treatment of skin-related diseases such as eczema, skin ulcers, measles, leprosy, wound, dermatitis, chickenpox, scabies, and ringworm [4][12][13]. Table 1 summarizes the traditional uses of P. speciosa.

plant using different types of extraction solvents.

Table 2. Phytochemical compounds extracted from P. speciosa plants. Adapted from Saleh et al. (2021) [4].

| Polyphenols | Plant Part | Extract | Country | References | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quercetin, rutin, kaempherol, catechin, luteolin, myricetin, gallic acid, caffeic acid, ferulic acid, trans-cinnamic acid, p-coumaric acid | Seed | Ethanol | Malaysia | [22] | |||||

| Diabetes | Singapore | ||||||||

| Gallic acid, catechin, chlorogenic acid, vanillic acid, caffeic acid, epicatechin, kaempferol, ellagic acid, cinnamic acid, ferulic aid, p-coumaric acid, quercetin | [ | 4 | Pod][14 | Aqueous, ethanol] | |||||

| Malaysia | [ | 23 | ] | – | Loss of appetite | Indonesia | |||

| Lupeol, β-sitosterol, stigmasterol, stigmasterol methyl ester, stigmasta-5,24(28)-diene-3-ol, campesterol, arachidonic acid, linoleic acid chloride, linoleic acid, squalene, lauric acid, stearic acid, oleic acid, myristic acid, lanthionine, ethyl linoleate, ethyl stearate, 3-ethyl-4-nonanol, eicosanoic acid, elaidic acid, 2-nonade-canone, 2-pyrrolidi-none, 2-decanal, cyclo-decanone-2,4-decadienal, Hexaminde, vitamin E | [ | 15 | Seed | Supercritical carbon dioxide] | |||||

| Malaysia | [ | 24 | ] | Cooked | Kidney disorder | West Malaysia | [16] | ||

| Apigenin, nobiletin, tangeritin, rutin, didymin, punicalin, coutaric acid, caftaric acid, malvidin, primulin | Pod | Methanol | Malaysia | [25] | Leaves | Pounded with rice and applied on the neck | Cough | Malaysia | [17] |

| Decoction | Dermatitis | Indonesia | [4][12] | ||||||

| – | Dermatitis | Indonesia | [15] | ||||||

| Root | |||||||||

| β-sitosterol, stigmasterol, stigmasterol methyl ester, campesterol, arachidonic acid, linoleic acid, linoleic acid chloride, linoleic acid, squalene, stearic acid, oleic acid, palmitic acid, myristic acid, undecanoic acid, stearolic acid, linoleaidic acid methyl ester | Seed | – | Malaysia | [26] | |||||

| 1,3-dithiabutane, 2,4-dithiapenthane, 2,3,5-trithiahexane, 2,4,6-trithiaheptane, pentanal | Seed | Aqueous | Indonesia | [27] | |||||

| 1,2,4-trithiolane, 1,3,5-trithaine, 3,5-dimethyl-1,2,4-trithiolane, dimethyl tetrasulfid, 1,2,5,6-tetrahio-cane, 1,2,3,5-tetrathiane, 1,2,4,5-tetrathiane, 1,2,4,6-tetrathie-pane, lethionine | Seed | Hexane | Singapore | [28] | Decoction | Skin conditions | Southern Thailand | [13] | |

| Decoction is taken orally | Hypertension and diabetes | Malaysia | [11][17] | ||||||

| Oral decoction | Toothache | Malaysia | [18] |

4. Phytochemistry

The bioactive compounds in plants can be classified into primary and secondary metabolites. Primary metabolites play a significant role in growth, development, or reproduction via molecules like amino acids, carbohydrates, and lipids [19][20]. The secondary metabolites derived from plants include flavonoids, alkaloids, saponins, triterpenes, tannins, and phytosterols; all of these are used by plants in their defense mechanisms [19][21]. P. speciosa also contains various types of polyphenols and flavonoids, which are believed to be potential sources of bioactive compounds beneficial to health. Table 2 documents the phytochemical compounds identified from different parts of the P. speciosa

References

- Suwannarat, K.; Nualsri, C. Genetic Relationships between 4 Parkia Spp. and Variation in Parkia speciosa Hassk. Based on Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA (RAPD) Markers. Songklanakarin J. Sci. Tech. 2008, 30, 433–440.

- Chhikara, N.; Devi, H.R.; Jaglan, S.; Sharma, P.; Gupta, P.; Panghal, A. Bioactive Compounds, Food Applications and Health Benefits of Parkia speciosa (Stinky Beans): A Review. Agric. Food Secur. 2018, 7, 46.

- Ahmad, N.I.; Rahman, S.A.; Leong, Y.-H.; Azizul, N.H. A Review on the Phytochemicals of Parkia Speciosa, Stinky Beans as Potential Phytomedicine. J. Food Sci. Nutr. Res. 2019, 2, 151–173.

- Saleh, M.S.M.; Jalil, J.; Zainalabidin, S.; Asmadi, A.Y.; Mustafa, N.H.; Kamisah, Y. Genus Parkia: Phytochemical, Medicinal Uses, and Pharmacological Properties. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 618.

- Siow, H.L.; Gan, C.Y. Extraction of Antioxidative and Antihypertensive Bioactive Peptides from Parkia speciosa Seeds. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 3435–3442.

- Asikin, Y.; Shikanai, T.; Wada, K. Volatile Aroma Components and MS-Based Electronic Nose Profiles of Dogfruit (Pithecellobium Jiringa) and Stink Bean (Parkia speciosa). J. Adv. Res. 2018, 9, 79–85.

- Azizul, N.H. Nutraceutical Potential of Parkia speciosa (Stink Bean): A Current Review. Am. J. Biomed. Sci. Res. 2019, 4, 392–402.

- Mondal, P.; Bhuyan, N.; Das, S.; Kumar, M.; Borah, S.; Mahato, K. Herbal Medicines Useful for the Treatment of Diabetes in North-East India: A Review. Int. J. Pharm. Biol. Sci. 2013, 3, 575–589.

- Boye, A.; Boampong, V.A.; Takyi, N.; Martey, O. Assessment of an Aqueous Seed Extract of Parkia clappertoniana on Reproductive Performance and Toxicity in Rodents. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 185, 155–161.

- Sheikh, Y.; Maibam, B.C.; Talukdar, N.C.; Deka, D.C.; Borah, J.C. In Vitro and in Vivo Anti-Diabetic and Hepatoprotective Effects of Edible Pods of Parkia roxburghii and Quantification of the Active Constituent by HPLC-PDA. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 191, 21–28.

- Azliza, M.A.; Ong, H.C.; Vikineswary, S.; Noorlidah, A.; Haron, N.W. Ethno-Medicinal Resources Used by the Temuan in Ulu Kuang Village. Stud. Ethno-Med. 2012, 6, 17–22.

- Roosita, K.; Kusharto, C.M.; Sekiyama, M.; Fachrurozi, Y.; Ohtsuka, R. Medicinal Plants Used by the Villagers of a Sundanese Community in West Java, Indonesia. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 115, 72–81.

- Srisawat, T.; Suvarnasingh, A.; Maneenoon, K. Traditional Medicinal Plants Notably Used to Treat Skin Disorders Nearby Khao Luang Mountain Hills Region, Nakhon Si Thammarat, Southern Thailand. J. Herbs Spices Med. Plants 2016, 22, 35–56.

- Siew, Y.Y.; Zareisedehizadeh, S.; Seetoh, W.G.; Neo, S.Y.; Tan, C.H.; Koh, H.L. Ethnobotanical Survey of Usage of Fresh Medicinal Plants in Singapore. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 155, 1450–1466.

- Bahtiar, A.; Vichitphan, K.; Han, J. Leguminous Plants in the Indonesian Archipelago: Traditional Uses and Secondary Metabolites. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2017, 12, 461–472.

- Samuel, A.J.S.J.; Kalusalingam, A.; Chellappan, D.K.; Gopinath, R.; Radhamani, S.; Husain, H.A.; Muruganandham, V.; Promwichit, P. Ethnomedical Survey of Plants Used by the Orang Asli in Kampung Bawong, Perak, West Malaysia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2010, 6, 5.

- Ong, H.C.; Chua, S.; Milow, P. Ethno-Medicinal Plants Used by the Temuan Villagers in Kampung Jeram Kedah, Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia. Stud. Ethno-Med. 2011, 5, 95–100.

- Ong, H.C.; Ahmad, N.; Milow, P. Traditional Medicinal Plants Used by the Temuan Villagers in Kampung Tering, Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia. Stud. Ethno-Med. 2011, 5, 169–173.

- Saxena, M.; Saxena, J.; Nema, R.; Singh, D.; Gupta, A. Phytochemistry of Medicinal Plants. J. Pharmacog. Phytochem. 2013, 1, 168–182.

- Tariq, A.L.; Reyaz, A.L. Significances and Importance of Phytochemical Present in Terminalia chebula. Int. J. Drug Dev. Res. 2013, 5, 256–262.

- Wadood, A. Phytochemical Analysis of Medicinal Plants Occurring in Local Area of Mardan. Biochem. Anal. Biochem. 2013, 2, 1000144.

- Ghasemzadeh, A.; Jaafar, H.Z.E.; Bukhori, M.F.M.; Rahmat, M.H.; Rahmat, A. Assessment and Comparison of Phytochemical Constituents and Biological Activities of Bitter Bean (Parkia speciosa Hassk.) Collected from Different Locations in Malaysia. Chem. Cent. J. 2018, 12, 12.

- Ko, H.J.; Ang, L.H.; Ng, L.T. Antioxidant Activities and Polyphenolic Constituents of Bitter Bean Parkia speciosa. Int. J. Food Prop. 2014, 17, 1977–1986.

- Azizi, C.Y.M.; Salman, Z.; Norulain, N.A.N.; Omar, A.K.M. Extraction and Identification of Compounds from Parkia speciosa Seeds by Supercritical Carbon Dioxide. J. Chem. Nat. Res. Eng. 2008, 2, 153–163.

- Kamisah, Y.; Zuhair, J.S.F.; Juliana, A.H.; Jaarin, K. Parkia speciosa Empty Pod Prevents Hypertension and Cardiac Damage in Rats given N(G)-Nitro-L-Arginine Methyl Ester. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 96, 291–298.

- Rahman, N.N.N.A.; Zhari, S.; Sarker, M.Z.I.; Ferdosh, S.; Yunus, M.A.C.; Kadir, M.O.A. Profile of Parkia speciosa Hassk Metabolites Extracted with SFE Using FTIR-PCA Method. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 2012, 59, 507–514.

- Frérot, E.; Velluz, A.; Bagnoud, A.; Delort, E. Analysis of the Volatile Constituents of Cooked Petai Beans (Parkia speciosa) Using High-Resolution GC/ToF-MS. Flavour Fragr. J. 2008, 23, 434–440.

- Tocmo, R.; Liang, D.; Wang, C.; Poh, J.; Huang, D. Organosulfide Profile and Hydrogen Sulfide-Releasing Capacity of Stinky Bean (Parkia speciosa) Oil: Effects of PH and Extraction Methods. Food Chem. 2016, 190, 1123–1129.

More