You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 3 by Lindsay Dong and Version 2 by Lindsay Dong.

Quercetin is a polyphenolic flavonoid plant secondary metabolite with a well-characterized antioxidant activity. It has been extensively reported as an anti-carcinogenic agent, and the modulated targets of quercetin have been also characterized in the context of colorectal cancer (CRC).

- quercetin

- flavonol

- polyphenol

- colorectal cancer

1. Quercetin

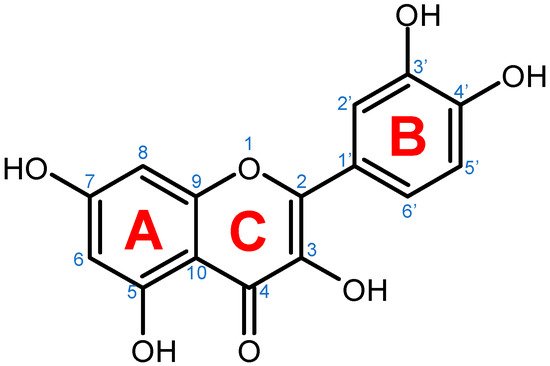

Quercetin is a plant pigment and secondary metabolite, a polyphenolic flavonoid phytochemical with a well-characterized antioxidant activity [1][2]. Chemically, it is a pentahydroxyflavone, using as a backbone the flavone structure C6(A-ring)-C3(C-ring)-C6(B-ring) (Figure 1) [2]. The official IUPAC name of the compound is 2-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-3,5,7-trihydroxy-4H-chromen-4-one and the chemical structure C15H10O7 [3][4]. The molecular weight of quercetin is 302,2 g/mol, and in its purified form it is a yellow-colored crystalline solid at room temperature, with poor water solubility, but increased solubility in alkaline aqueous solutions and alcohols, having a low acute toxicity level through oral exposure at LD50 161 mg/kg [2][5]. The average daily intake is approximately 25 mg according to the US Department of Health and Human Services and studies carried out in Japan, France, and Finland [6][7][8][9][10], due to consumption of major food sources such as onions, asparagus, and berries, while reduced quantities are acquired from various other plants (Table 1) [11][12].

Figure 1. Chemical structure of quercetin with numbered carbon atoms (blue) and marked rings (red) on the general flavonoid backbone structure.

Table 1. Dietary sources with quercetin concentrations higher than 10 mg/100 g fresh weight according to the United States Department of Agriculture Database for the Flavonoid Content of Selected Foods.

Source: USDA (United States Department of Agriculture) Database for the Flavonoid Content of Selected Foods [12].

| Plant | Quercetin Concentration |

|---|---|

| (mg/100 g Fresh Weight) | |

| Dill | 79.0 |

| Fennel leaves | 46.8 |

| Onion | 45.0 |

| Oregano | 42.0 |

| Chili pepper | 32.6 |

| Spinach | 27.2 |

| Cranberry | 25.0 |

| Kale | 22.6 |

| Cherry | 17.4 |

| Lettuce | 14.7 |

| Blueberry | 14.6 |

| Asparagus | 14.0 |

| Broccoli | 13.7 |

| Chives | 10.4 |

2. Quercetin and Its Derivatives—Mechanisms of Action in CRC

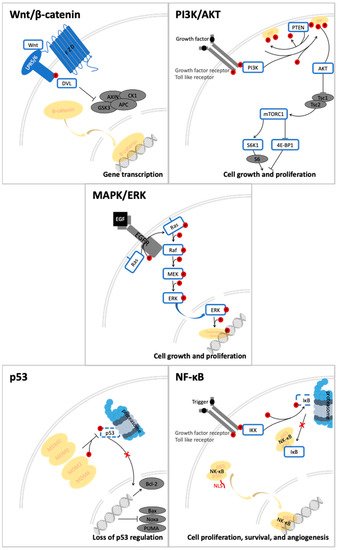

Quercetin and its derivatives act on a multitude of targets involved in the initiation and promotion/progression phases of colorectal cancer (CRC) carcinogenesis, as described in established cell lines and other animal models of the disease. Among the anti-carcinogenic activities of quercetin, the most notable described in CRC are inhibition of cellular proliferation and growth, cell cycle arrest, induction of apoptosis, reduction in tumor size, decrease in number of tumor nodule, suppression of metastasis, decrease in inflammation, decrease in ROS (i.e., antioxidant activity), and reduction in multidrug resistance. Well documented in cell culture and rodent studies, the mechanisms of action and targets of quercetin mainly involve members of the pathways Wnt/β-catenin, PI3K/AKT/mTOR, MAPK/Erk, MAPK/JNK, MAPK/p38, p-53, and NF-κB (Figure 2), [13][14][15][16].

Figure 2. Signal transduction pathways in CRC that are modulated by quercetin: Wnt/β-catenin, PI3K/AKT, MAPK (using MAPK/ERK as an example for the phosphorylation cascade), p53, and NF-κB.

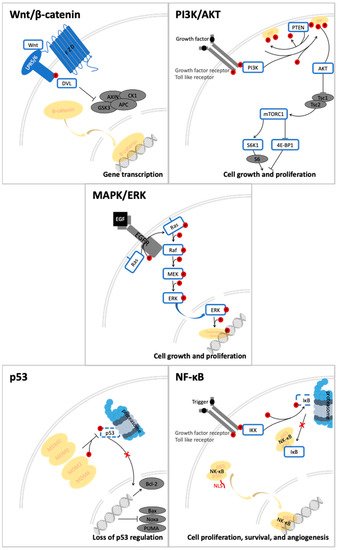

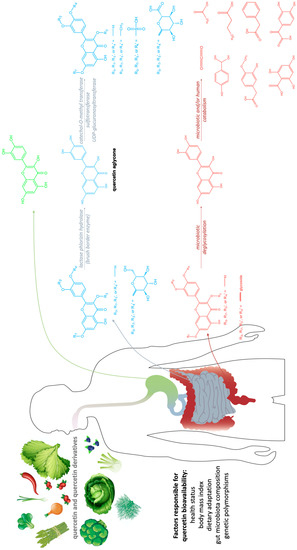

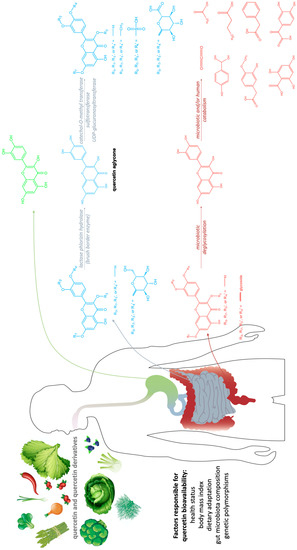

Figure 3. Quercetin metabolism in the gastro-intestinal tract. Green—stomach absorption; blue—small intestine absorption; red—large bowel absorption.

The serine/threonine protein kinase mTOR consists of two multiprotein complexes: mTORC1 and mTORC2 [27], with the regulatory-associated protein of mTOR and the proline-rich AKT substrate of 40 KDa (PRAS40) being distinctive for the mTORC1 complex [28][29] and the rapamycin-insensitive companion of mTOR, the protein observed with RICTOR 1/2, and the mammalian stress-activated protein kinase-interacting protein 1 being distinctive for the mTORC2 complex [30][31][32]. While the molecular functions of mTORC2 were not fully elucidated, mTORC1 has been attributed several functions, some of which are vital pivots in the development of CRC. The most relevant upstream regulators of mTORC1 suffering genetic alterations in the context of CRC are: PIK3CA gene-gain-of-function mutations [33][34], PTEN gene-inactivating mutations [34], or the STK11/LKB1 gene [35], which encodes for an mTORC1 repressor. CRC reported mutations in the mTOR genes themselves are not as ubiquitous, while in the same pathway, the most seldom are the AKT gene mutations [36].

The mitogenic stimuli PI3K and AKT are the main activators of mTORC1 in the pathological context of CRC [37]. PI3K enzyme catalyzes the conversion of phosphatidylinositol (3,4)-bisphosphate into phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate, therefore triggering the phosphorylation of AKT [38]. Then, the AKT-mediated phosphorylation of mTORC1 takes place. This entails the phosphorylation of two main downstream targets: the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (eIF4E) binding protein 1 (4E-BP1) and the S6 kinase 1 [39][40]. It is followed by 4E-BP1 dissociation from eIF4E, leading to mRNA translation activation, whilst S6K1 activation facilitates the phosphorylation of the S6 ribosomal protein leading to initiation and elongation of translation [41].

Figure 3. Quercetin metabolism in the gastro-intestinal tract. Green—stomach absorption; blue—small intestine absorption; red—large bowel absorption.

The serine/threonine protein kinase mTOR consists of two multiprotein complexes: mTORC1 and mTORC2 [27], with the regulatory-associated protein of mTOR and the proline-rich AKT substrate of 40 KDa (PRAS40) being distinctive for the mTORC1 complex [28][29] and the rapamycin-insensitive companion of mTOR, the protein observed with RICTOR 1/2, and the mammalian stress-activated protein kinase-interacting protein 1 being distinctive for the mTORC2 complex [30][31][32]. While the molecular functions of mTORC2 were not fully elucidated, mTORC1 has been attributed several functions, some of which are vital pivots in the development of CRC. The most relevant upstream regulators of mTORC1 suffering genetic alterations in the context of CRC are: PIK3CA gene-gain-of-function mutations [33][34], PTEN gene-inactivating mutations [34], or the STK11/LKB1 gene [35], which encodes for an mTORC1 repressor. CRC reported mutations in the mTOR genes themselves are not as ubiquitous, while in the same pathway, the most seldom are the AKT gene mutations [36].

The mitogenic stimuli PI3K and AKT are the main activators of mTORC1 in the pathological context of CRC [37]. PI3K enzyme catalyzes the conversion of phosphatidylinositol (3,4)-bisphosphate into phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate, therefore triggering the phosphorylation of AKT [38]. Then, the AKT-mediated phosphorylation of mTORC1 takes place. This entails the phosphorylation of two main downstream targets: the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (eIF4E) binding protein 1 (4E-BP1) and the S6 kinase 1 [39][40]. It is followed by 4E-BP1 dissociation from eIF4E, leading to mRNA translation activation, whilst S6K1 activation facilitates the phosphorylation of the S6 ribosomal protein leading to initiation and elongation of translation [41].

Abbreviations: ANXA1 = Annexin A1; CB1 receptor = Cannabinoid receptor type 1; MYC = Myelocytomatosis oncogene product; p-4E-BP1 = phosphorylated Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E binding protein 1; p-AKT = phosphorylated Protein kinase B; p-GSK3β = phosphorylated Glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta; p-PI3K = phosphorylated Phosphoinositide 3-kinase; p-S6 = phosphorylated Ribosomal protein S6; p-STAT3 = phosphorylated Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; PCNA = Proliferating cell nuclear antigen; Wnt/β-catenin = Wingless-related integration site/β-catenin pathway.

Quercetin inhibits in cell culture the activity of AKT (also known as protein kinase B) by hindering it from phosphorylation, thus decreasing the concentration of p-AKT, in several CRC representative cell lines, such as HT-29 [70][72], Caco-2 [71], DLD-1 [71], and HCT-15 [72].

In vivo, Wistar rats and F344 rats, studies claim a decrease in proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) and annexin A1 (ANXA1) upon dietary ingestion of quercetin in comparison to the control group [73][74]. PCNA, originally a DNA sliding clamp for replicative polymerases and vital component of the eukaryotic chromosomal DNA replisome, has been revealed to interact with multiple partners, involved in DNA repair, Okazaki fragment processing, DNA methylation, and chromatin remodeling [81]. ANXA1, also known as lipocortin I, is a member of the annexin multigene superfamily of Ca2+-regulated, phospholipid-dependent, membrane-binding proteins [82]. In CRC, ANXA1 upregulation is correlated with the MAPK cascades upregulation, as its concentration is directly proportional with the K-RAS concentration [82][83][84].

Abbreviations: Bax = Bcl-2 Associated X-protein; Bcl-2 = B-cell lymphoma 2; CDC6 = Cell division cycle 6 regulatory protein; CDC25c = Cell division cycle 25c regulatory protein; CDK1 = Cyclin dependent kinase 1; CDK4 = Cyclin dependent kinase 1; Ki67 = nonhistone nuclear protein KI67; p-AKT = phosphorylated Protein kinase B; p21 = Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1; p53 = Tumor protein p53; p58 = p58 Natural killer cell inhibitory receptor.

Abbreviations: AKT = Protein kinase B; AMPK = 5′ adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase; Apaf-1 = Apoptotic protease activating factor 1; APC = Adenomatous polyposis coli; Bax = Bcl-2 Associated X-protein; Bcl-2 = B-cell lymphoma 2; Bcl-xL = B-cell lymphoma extra-large; c-Jun = AP-1 transcription factor subunit; COX-2 = cyclooxygenase-2; GPx = Glutathione peroxidase; HIF-1 = Hypoxia-inducible factor 1; JNK = c-Jun N-terminal kinases; KRAS = Kirsten rat sarcoma virus; MMP = Matrix metalloproteinases; MMP-2 = Matrix metalloproteinase 2; MMP-9 = Matrix metalloproteinase 9; NF-κB = Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B-cells; p-AKT = phosphorylated Protein kinase B; p-AMPK = phosphorylated 5′ adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase; p-ERK = phosphorylated Extracellular signal-regulated kinase; p-JNK = phosphorylated c-Jun N-terminal kinases; p-mTOR = phosphorylated Mammalian target of rapamycin; p-p38 = phosphorylated Mitogen-activated protein kinase p38; PARP = Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase; PI3K = Phosphoinositide 3-kinases; SIRT-2 = NAD-dependent deacetylase sirtuin 2; Snail = Zinc finger protein SNAI1; TSC22 domain family 3 = Glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper protein; Wnt1 = Proto-oncogene Wnt-1.

3. Crucial Signal Transduction Pathways in CRC

3.1. Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling in CRC

The critical role of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway (Figure 2) in the etiology of CRC has been thoroughly studied; thus, light has been shed on the molecular mechanisms of interaction and the signal transduction regulation. Genetic alterations in the members of Wnt/β-catenin pathway lead to the intrinsic aberrant canonical Wnt/β-catenin activation, mainly stemming from mutations in the APC, AXIN1, and AXIN2 genes [17]. Physiologically, β-catenin levels are maintained at sub-critical levels through the dynamic activity of the degradosome complex, consisting of the glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3), axis inhibition protein 1 (AXIN1), adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), E3-ubiquitin ligase β-TrCP, protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A), and casein kinase 1α (CK1α) [18]. While the scaffold proteins in the complex are APC and AXIN1, the CK1α and GSK3 are responsible for β-catenin phosphorylation as serine/threonine kinases [19]. Once phosphorylated, E3-ubiquitin ligase β-TrCP mediates its ubiquitination and targets it for degradation by the proteasome machinery [17][20]. Pathologically, the Wnt ligands bind the 7-transmembrane receptor frizzled (FZD) family and its co-receptors low-density lipoprotein receptors 5 and 6 (LRP5/6) [21][22]. The ligand-receptor complex Wnt-FZD-LRP5/6 assembly with recruitment of the Dishevelled (DVL) adaptor by FZD facilitates the phosphorylation of LRP6 [23]. This leads to a cascade of molecular interactions including its association with AXIN1, their translocation to the plasma membrane, the dissociation of GSK3 from AXIN1 and APC, and concomitant stabilization of β-catenin by dephosphorylation [23][24]. Thereafter, the signalosome is assembled, a multiprotein complex that transduces Wnt signals, and the degradosome is disassembled leading to β-catenin accumulation in the cytosol and its subsequent nuclear translocation [23]. Nuclear β-catenin acts as a transcriptional activator inducing the transcription of target genes, among which are c-MYK [25] and AXIN2 [26], hereafter activating the oncogenic mechanisms [17].23.2. PI3K/AKT-mTOR Signaling in CRC

Another relevant signal transduction pathway in CRC development and progression is the PI3K/AKT/mTOR cascade (Figure 2). It tightly interacts with the previously mentioned Wnt/β-catenin pathway, as blockage of, more accurately, PI3K/AKT/mTORC1 leads to hyperactivation of the Wnt/β-catenin as compensatory mechanism (Figure 3) [17]. Figure 3. Quercetin metabolism in the gastro-intestinal tract. Green—stomach absorption; blue—small intestine absorption; red—large bowel absorption.

The serine/threonine protein kinase mTOR consists of two multiprotein complexes: mTORC1 and mTORC2 [27], with the regulatory-associated protein of mTOR and the proline-rich AKT substrate of 40 KDa (PRAS40) being distinctive for the mTORC1 complex [28][29] and the rapamycin-insensitive companion of mTOR, the protein observed with RICTOR 1/2, and the mammalian stress-activated protein kinase-interacting protein 1 being distinctive for the mTORC2 complex [30][31][32]. While the molecular functions of mTORC2 were not fully elucidated, mTORC1 has been attributed several functions, some of which are vital pivots in the development of CRC. The most relevant upstream regulators of mTORC1 suffering genetic alterations in the context of CRC are: PIK3CA gene-gain-of-function mutations [33][34], PTEN gene-inactivating mutations [34], or the STK11/LKB1 gene [35], which encodes for an mTORC1 repressor. CRC reported mutations in the mTOR genes themselves are not as ubiquitous, while in the same pathway, the most seldom are the AKT gene mutations [36].

The mitogenic stimuli PI3K and AKT are the main activators of mTORC1 in the pathological context of CRC [37]. PI3K enzyme catalyzes the conversion of phosphatidylinositol (3,4)-bisphosphate into phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate, therefore triggering the phosphorylation of AKT [38]. Then, the AKT-mediated phosphorylation of mTORC1 takes place. This entails the phosphorylation of two main downstream targets: the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (eIF4E) binding protein 1 (4E-BP1) and the S6 kinase 1 [39][40]. It is followed by 4E-BP1 dissociation from eIF4E, leading to mRNA translation activation, whilst S6K1 activation facilitates the phosphorylation of the S6 ribosomal protein leading to initiation and elongation of translation [41].

Figure 3. Quercetin metabolism in the gastro-intestinal tract. Green—stomach absorption; blue—small intestine absorption; red—large bowel absorption.

The serine/threonine protein kinase mTOR consists of two multiprotein complexes: mTORC1 and mTORC2 [27], with the regulatory-associated protein of mTOR and the proline-rich AKT substrate of 40 KDa (PRAS40) being distinctive for the mTORC1 complex [28][29] and the rapamycin-insensitive companion of mTOR, the protein observed with RICTOR 1/2, and the mammalian stress-activated protein kinase-interacting protein 1 being distinctive for the mTORC2 complex [30][31][32]. While the molecular functions of mTORC2 were not fully elucidated, mTORC1 has been attributed several functions, some of which are vital pivots in the development of CRC. The most relevant upstream regulators of mTORC1 suffering genetic alterations in the context of CRC are: PIK3CA gene-gain-of-function mutations [33][34], PTEN gene-inactivating mutations [34], or the STK11/LKB1 gene [35], which encodes for an mTORC1 repressor. CRC reported mutations in the mTOR genes themselves are not as ubiquitous, while in the same pathway, the most seldom are the AKT gene mutations [36].

The mitogenic stimuli PI3K and AKT are the main activators of mTORC1 in the pathological context of CRC [37]. PI3K enzyme catalyzes the conversion of phosphatidylinositol (3,4)-bisphosphate into phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate, therefore triggering the phosphorylation of AKT [38]. Then, the AKT-mediated phosphorylation of mTORC1 takes place. This entails the phosphorylation of two main downstream targets: the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (eIF4E) binding protein 1 (4E-BP1) and the S6 kinase 1 [39][40]. It is followed by 4E-BP1 dissociation from eIF4E, leading to mRNA translation activation, whilst S6K1 activation facilitates the phosphorylation of the S6 ribosomal protein leading to initiation and elongation of translation [41].

3.3. MAPK Cascades in CRC

The mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades (Figure 2) represent a set of membrane-to-nucleus signaling pathways that result in phosphorylation and activation of transcription factors [42]. With MAPK being members of the Ser/Thr kinases family, multiple rounds of subsequent phosphorylation-activating kinases are triggered [43]. There are three distinct MAPK cascades: MAPK/Erk (extracellular-signal-regulated kinases), MAPK/JNK (c-Jun N-terminal or stress-activated protein kinases), and MAPK/p38 [43]. As all pathways can be targeted (up- and down-regulated) by quercetin in the context of CRC, they will be the further discussed in the current publication. Several proto-oncogenes are responsible for the involvement of the MAPK cascades in the development of CRC. The aberrations include the gain-of-function KRAS and BRAF gene mutations and upregulation of JUN gene [44]. Moreover, the role of EGFR is noteworthy in the MAPK activation and upregulation relevant in CRC [44].3.3.1. MAPK/ERK Signaling in CRC

EGFR, a transmembrane protein, member of the ErbB family of receptors, functions as a receptor tyrosine kinase located upstream of MAPK pathways [43]. The three Ras small GTPases are H-Ras, N-Ras, and K-Ras [45], while the most relevant Raf kinases are A-Raf, B-Raf and C-Raf (Raf1) [46]. Through the phosphorylation of the inactive form of Ras-family GTPases bound to GDP to the active form bound to GTP, external signals are transmitted from receptors on the cytoplasmic membrane to the interior of the cell [47]. The adaptor complex then activates Ras-GTP. Post RAS activation, there is a phosphorylation-dependent cascade, activating RAF, MEK, and, finally, ERK. The activation of the ERK/MAPK pathway is reported to also induce the synthesis of cyclin D1, relevant in the progression of cell cycle [48]. Moreover, Raf1 creates a link between the MAPK/ERK pathway and PI3K/AKT, allowing the possibility of correlated feedback between the two distinct metabolic paths, both upregulated in the CRC pathology [44].3.3.2. MAPK/JNK Signaling in CRC

The JNK cascade is used by the transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ) in order to autoregulate its concentration; however, it does not affect the JNK protein expression [49]. The pathway activation induced by TGFβ can act in conjunction with SMADs or in SMAD-independent manner [42][44]. The latter is acting on the MKK4–TGFβ-activated kinase 1 (TAK1) axis [49][50], where TAK1 is activated by the tumor necrosis factor-receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6), TGFβR2, and TGFβR1 protein complex [49]. Thereafter, it activates the JNK/p38 pathways [49], culminating in the formation of the ICD, domain of TGFβR1, consequent to ubiquitination and TNF-alpha converting enzyme cleavage [43]. ICD is able to translocate into the nucleus, where it induces the overexpression of Snail, MMP2, and p300 genes [51].3.3.3. MAPK/ p38 Signaling in CRC

The MAPK/p38 pathway becomes activated in response to stressors such as hypoxia, heat shock, and osmotic shock [43]. p38 signaling is required for cell migration and metastasis in both CRC and breast cancer [52][53]. Similar to JNKs, p38 MAPKs are activated through autophosphorylation by MKKs [49][50]. TAK1 and TRAF6 are responsible for the SMAD-independent activation of p38. At this level, there is crosstalk in between TAK1 and the NF-κB-MMP9 pathway, another relevant carcinogenesis pathway reported in CRC. The blockade of p38 MAPK activity leads to the recovery of cell cycle and induction cell death mainly through autophagy [53][54].5.4. p53 Signaling in CRC

3.4. p53 Signaling in CRC

TP53, a tumor suppressor gene, is among the most commonly mutated genes in CRC and various other types of cancer, with mutations mainly in the exons 5 to 8 (DNA binding domain) [55][56][57]. p53 is physiologically expressed at low levels, partly due to the negative feedback loops that involve MDM2. MDM2 is a transcriptional target of p53 that mediates the degradation of p53 through negative feedback and by functioning as an E3 ubiquitin-ligase that regulates the ubiquitination of p53 [58][59]. Low levels of p53 expression maintain homoeostasis of the cell cycle and cell death. A homolog of MDM2, namely, MDM4, not regulated by p53, forms heterodimers with MDM2 and can enhance MDM2 induced p53 degradation [58]. As a response to stress factors, such as oncogenes, DNA damage, UV irradiation, free radicals, hypoxia, or deficiencies in nutrients and growth factors, p53 is also activated (Figure 4). Then, it can either repress or transactivate downstream targets that regulate cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, DNA repair, and angiogenesis and metastasis [60]. Upon activation, under normal conditions, it can trigger both the intrinsic, mitochondrial, and the extrinsic, death-receptor-induced, apoptotic pathways [61]. The upregulation of expression takes place for the pro-apoptotic B-cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2) proteins, such as Bax, Noxa, and PUMA, while the pro-survival Bcl-2 members are downregulated, under normal conditions. This leads to the permeabilization of the mitochondrial outer membrane, releasing cytochrome-c, which binds to Apaf-1, activating the caspase-9. Thereafter, caspase-9 acts as initiator of the cascade, activating caspase-3, caspase-6, and caspase-7 [62]. Among the p53 upregulated death receptors, the most relevant would be PIDD (p53-induced protein with death domain), DR5 (TRAIL-R2), and Fas (CD95/APO-1), which alongside caspase-8 form the death-inducing signaling complexes acting in a loop and in turn activate p53 [59]. Moreover, the transcription factor (TF), TP53, is additionally involved in the genetic modulation including several miRNAs [55][60]. In the cell cycle, under normal conditions, p53 induces the G1/S and G2/M arrest via interactions with targets such as p21(WAF1), GADD45, retinoblastoma protein (Rb), and 14-3-3σ, also cRRIMA-1MET [59].3.5. NF-κB Signaling in CRC

NF-κB is a heterodimer protein, consisting of the p65 and p50 subunits, which are required for its activation and translocation to the nucleus (Figure 2) [63][64]. Physiologically, in most quiescent cells it is retained in the cytoplasm by I-kappa B (IκB), which covers its nuclear localization sequence (NLS) [65]. Pathologically, the IκB kinase (IKK) complex, containing the NEMO regulatory subunit and the IKKα and IKKβ catalytic subunits, is upregulated by external stimuli through receptors such as the tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR), the Toll-like receptor (TLR), and the T/B cell receptor [63][66]. In turn, it phosphorylates IκB, which then is degraded via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, allowing thereafter the nuclear translocation of NF-κB [63]. Inside the nucleus, it triggers down-stream gene expression by binding to the enhancer element of the immunoglobulin kappa light-chain, leading to inflammation and cancer development or progression [66][67][68]. In CRC adenocarcinoma, the abnormal activity of K-RAS is directly proportional with the expression of NF-κB [69].4. Quercetin Impacts the Growth and Proliferation in CRC

In the development of CRC, cellular growth and proliferation mechanisms need to be altered for the progression of the disease. It is noteworthy that quercetin is documented, in Table 2, as an inhibitor of these processes both in vivo and in vitro [70][71][72][73][74][75][76][77][78][79][80].

Table 2. Reported targets of quercetin active in the reduction in cellular growth and proliferation of CRC models alongside their in vivo/in vitro testing system. “↓” arrows are indicating the downregulation, while “?” denotes the lack of specific targets in the respective studies.| ? |

| In vivo: F344 AOM treated rats |

| [ |

| 80 |

| ] |

5. Quercetin Impacts the Cell Cycle in CRC

Even though highly related to the previously described section, the targets of quercetin in the cell cycle arrest might slightly differ, while the activity is mainly described regarding the phase in which the cells are resting (Table 3). Table 3. Reported targets of quercetin active in cell cycle arrest of CRC models alongside their in vivo/in vitro testing system. “↑” and “↓” arrows are indicating the up- and downregulation, respectively, while “?” denotes the lack of specific targets in the respective studies.| Cell Cycle Arrest Phase and/or Molecular Targets | Testing System | Reference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At G0/G1 phase | In vivo: HCT-116 Xenograft mouse model | [85] | ||||

| ↑ JNK, c-Jun | In vitro: Caco-2 and DLD-1 cell cultures | [71] | ? | |||

| At G0/G1 phase | In vitro: HT-29 cell culture | [70] | ||||

| ? | ||||||

| At G1 or G2 | In vitro: HCT-116 cell culture | [77] | ||||

| ? | ||||||

| ↑ COX-2 | In vitro: HT-29 and HCT-15 cell cultures | [72] | ||||

| ↑ Caspase-3, Cytochrome-c | ||||||

| ↑ Bax, PARP, APC | In vivo: Wistar rats | [73] | At G2/M | In vitro: HT-29, HCT116 and SW480 cell cultures | ||

| ↓ Bcl-2, β-catenin | [ | 86] | ||||

| ↓ p-AKT | ||||||

| ↓ p-ERK, KRAS | In vitro: HCT-15 cell culture | [74] | ||||

| ↓ TSC22 domain family 3 | In vivo: F344 rats | [74] | ||||

| ↓ p-AKT, KRAS | In vitro: CO115 cell culture | [74] | ↑ Cyclin B1 | |||

| ↓ PI3K, AKT, p-AKT, Bcl-2 | In vitro: HCT-116 and HT29 cell cultures | [75] | At G2/M | ↑ Bax | In vitro: RKO cell culture | [87] |

| ↓ CDK1, CDC25c, Cyclin B1 | ||||||

| ↑ Caspase-3, p-JNK | In vitro: DLD-1 | ↑ p21 | ||||

| KRASG13D | and DLD-1KRASWT cell cultures | [76] | ||||

| ↓ p-AKT | At G2/M | In vitro: SW620 cell culture | [88] | |||

| ↑ Caspase-3, Cytochrome-c | In vitro: RKO and CCD841 cell cultures | [79] | ↑ p21, p58 | |||

| ↓ AMPK, HIF-1 | In vitro: HCT-116 | [85] | ↓ CDC6, CDK4, Cyclin D1 | In vitro: Caco-2 cell culture | [89] | |

| ↓ Bcl-2 | In vitro: RKO cell culture | [87] | ↓ Ki67 | In vitro: SW480 cell culture | [90] | |

| ↓ Bcl-2 | In vitro: HT-29 cell culture | [70] | ||||

| ↑ Bax, p53, Caspase-3 |

6. Quercetin Impacts Apoptosis in CRC

Alongside suppression of proliferation, induction of apoptosis increases the theoretical benefits of an anti-cancer agent. In this regard, quercetin takes both approaches against cancer development, with a plentitude of targets, mainly pertaining to signal transduction pathways (Table 4). Table 4. Reported targets of quercetin active in induction of apoptosis of CRC models alongside their in vivo/in vitro testing system. “↑” and “↓” arrows are indicating the up- and down-regulation, respectively, while “?” denotes the lack of specific targets in the respective studies.| Molecular Targets | Testing System | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| ↑ Bax, cleaved-Caspase-3, cleaved-Caspase-9 | ||

| ↑ Bax, Cytochrome-c, Caspase-9, Apaf-1, Caspase-3 | ||

| In vitro: SW620 cell culture | ||

| [ | ||

| 88 | ||

| ] | ||

| ↓ GPx, Catalase | ||

| ↓ PI3K, AKT ↑ Caspase-3, Bax | ||

| In vitro: SW480 cell culture | [ | 90] |

| ↑ PARP, cleaved-Caspase-3, cleaved-Caspase-9 | In vitro: CT-26 cell culture | [91] |

| ↓ Bcl-2, Bcl-xL | ||

| ↓ MMP-2, MMP-9, N-cadherin, β-catenin, Snail | In vivo: mouse model of CRC lung metastasis | [91] |

| ↑ E-cadherin | ||

| ↑ p53, BAX, p-p38 ↓ Bcl-2 |

In vitro: HCT-15 cell culture | [92] |

| ↑ p53, cleaved-Caspase 3, cleaved-Caspase 9, PARP, cleaved-PARP ↓ Bcl-2 |

In vitro: CO115 cell culture | [92] |

| ↑ Bax, Caspase-3, Caspase-9 | In vitro: Caco-2 and SW-620 cell cultures | [93] |

| ↓ Bcl-2, NF-κB | ||

| ↓ MMP | In vitro: DLD-1 cell culture | [94] |

| ↓ MMP | In vitro: HCT-116 cell culture | [95] |

| ↑ SIRT-2, p-AMPK, p-p38 | In vitro: HCT-116 cell culture | [96] |

| ↓ p-mTOR | ||

| ↑ Caspase-3, cleaved-PARP, p-p38 | In vitro: DLD-1 cell culture | [97] |

| ↓ Bcl-2, Cyclin D1, | In vitro: Colo320 cell culture | [98] |

| ↑ Bax, Caspase-3, Wnt1, Catalase | ||

| ? | In vivo: AOM/DSS-treated wild-type C57BL/6J mice | [99] |

| ? | In vitro: HCT-116 cell culture | [77] |

| ? | In vitro: HCT-116 cell culture | [80] |

| ? | In vitro: HCT-116p53-wt, HCT-116p53-null, HCT-15KRAS-mutated cell culture | [92] |

| ? | In vitro: CT-26 cell culture | [100] |

| Molecular Targets | Testing System | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| ↓ p-AKT, MYC | In vitro: HT-29 cell culture | [70] |

| ↓ CB1 receptor, Wnt/β-catenin, p-GSK3β, | In vitro: Caco-2 and DLD-1 cell cultures | [71] |

| p-PI3K, p-AKT, p-S6, p-4E-BP1, p-STAT3 | ||

| ↓ p-AKT, p-GSK3β, Cyclin D1 | In vitro: HT-29 and HCT-15 cell cultures | [72] |

| ↓ PCNA | In vivo: Wistar rats | [73] |

| ↓ ANXA1 | In vivo: F344 rats | [74] |

| ? | In vitro: HCT-116 and HT-29 cell cultures | [75] |

| ? | In vitro: DLD-1KRASG13D, DLD-1KRASWT, SW480KRASG12V, HCT-116KRASG13D, Colo205KRASWT, WIDRKRASWT, and HT-29 KRASWT cell cultures | [76] |

| ? | In vitro: HCT-116 cell culture | [77] |

| ? | In vitro: HCT15 and CO115 cell cultures | [74] |

| ? | In vitro: HCT-116 cell culture | [78] |

| ? | In vitro: RKO and CCD841 cell cultures | [79] |

7. Quercetin Impacts Tumor Size in CRC

In the case of the PI3K/AKT and p53 pathways, the quercetin-induced modulation is in accordance with its expected anticarcinogenic activity [90]. However, in the case of the MAPK cascades, the modulation seems to act in anti-apoptotic and pro-proliferative manner, even though the quantification of the tumor size contradicts this in the testing system [91]. Nevertheless, all studies attest that the tumors decreased in size upon quercetin supplementation, supporting, through an additional argument, the potential benefits of testing quercetin alongside chemo- and radiotherapy in clinical setting.References

- Xu, D.; Hu, M.J.; Wang, Y.Q.; Cui, Y.L. Antioxidant Activities of Quercetin and Its Complexes for Medicinal Application. Molecules 2019, 24, 1123.

- Singh, P.; Arif, Y.; Bajguz, A.; Hayat, S. The role of quercetin in plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 166, 10–19.

- Hastings, J.; Owen, G.; Dekker, A.; Ennis, M.; Kale, N.; Muthukrishnan, V.; Turner, S.; Swainston, N.; Mendes, P.; Steinbeck, C. ChEBI in 2016: Improved services and an expanding collection of metabolites. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 44, D1214–D1219.

- Law, V.; Knox, C.; Djoumbou, Y.; Jewison, T.; Guo, A.C.; Liu, Y.; Maciejewski, A.; Arndt, D.; Wilson, M.; Neveu, V.; et al. DrugBank 4.0: Shedding new light on drug metabolism. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, D1091–D1097.

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem Compound Summary for CID 5280343, Quercetin. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Quercetin (accessed on 12 February 2022).

- Reyes-Farias, M.; Carrasco-Pozo, C. The anti-cancer effect of quercetin: Molecular implications in cancer metabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3177.

- Stavric, B. Quercetin in our diet: From potent mutagen to probable anticarcinogen. Clin. Biochem. 1994, 27, 245–248.

- Nishimuro, H.; Ohnishi, H.; Sato, M.; Ohnishi-Kameyama, M.; Matsunaga, I.; Naito, S.; Kobori, M. Estimated daily intake and seasonal food sources of quercetin in Japan. Nutrients 2015, 7, 2345–2358.

- Perez-Jimenez, J.; Fezeu, L.; Touvier, M.; Arnault, N.; Manach, C.; Hercberg, S.; Galan, P.; Scalbert, A. Dietary intake of 337 polyphenols in French adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 93, 1220–1228.

- Ovaskainen, M.L.; Torronen, R.; Koponen, J.M.; Sinkko, H.; Hellstrom, J.; Reinivuo, H.; Mattila, P. Dietary intake and major food sources of polyphenols in Finnish adults. J. Nutr. 2008, 138, 562–566.

- Dabeek, W.M.; Marra, M.V. Dietary quercetin and kaempferol: Bioavailability and potential cardiovascular-related bioactivity in humans. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2288.

- Bhagwat, S.; Haytowitz, D.B. USDA Database for the Flavonoid Content of Selected Foods. Release 3.2 (November 2015). Nutrient Data Laboratory, Beltsville Human Nutrition Research Center, ARS, USDA. Available online: https://data.nal.usda.gov/dataset/usda-database-flavonoid-content-selected-foods-release-32-november-2015 (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Arts, I.C.W.; Sesink, A.L.A.; Faassen-Peters, M.; Hollman, P.C.H. The type of sugar moiety is a major determinant of the small intestinal uptake and subsequent biliary excretion of dietary quercetin glycosides. Br. J. Nutr. 2004, 91, 841–847.

- Cermak, R.; Landgraf, S.; Wolffram, S. The bioavailability of quercetin in pigs depends on the glycoside moiety and on dietary factors. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 2802–2807.

- Reinboth, M.; Wolffram, S.; Abraham, G.; Ungemach, F.R.; Cermak, R. Oral bioavailability of quercetin from different quercetin glycosides in dogs. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 104, 198–203.

- Russo, M.; Spagnuolo, C.; Tedesco, I.; Bilotto, S.; Russo, G.L. The flavonoid quercetin in disease prevention and therapy: Facts and fancies. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2012, 83, 6–15.

- Prossomariti, A.; Piazzi, G.; Alquati, C.; Ricciardiello, L. Are Wnt/β-Catenin and PI3K/AKT/mTORC1 distinct pathways in colorectal cancer? Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 10, 491–506.

- Stamos, J.L.; Weis, W.I. The β-catenin destruction complex. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013, 5, a007898.

- Li, Y.; Semenov, M.; Han, C.; Baeg, G.-H.; Tan, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, X.; He, X. Control of β-catenin phosphorylation/degradation by a dual-kinase mechanism. Cell 2002, 108, 837–847.

- Aberle, H.; Bauer, A.; Stappert, J.; Kispert, A.; Kemler, R. β-catenin is a target for the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway. EMBO J. 1997, 16, 3797–3804.

- Dann, C.E.; Hsieh, J.C.; Rattner, A.; Sharma, D.; Nathans, J.; Leahy, D.J. Insights into Wnt binding and signalling from the structures of two Frizzled cysteine-rich domains. Nature 2001, 412, 86–90.

- Tamai, K.; Semenov, M.; Kato, Y.; Spokony, R.; Liu, C.; Katsuyama, Y.; He, X. LDL-receptor-related proteins in Wnt signal transduction. Nature 2000, 407, 530–535.

- Zeng, X.; Tamai, K.; Doble, B.; Li, S.; Huang, H.; Habas, R.; He, X. A dual-kinase mechanism for Wnt co-receptor phosphorylation and activation. Nature 2005, 438, 873–877.

- Molenaar, M.; Van De Wetering, M.; Oosterwegel, M.; Peterson-Maduro, J.; Godsave, S.; Korinek, V.; Clevers, H. XTcf-3 transcription factor mediates β-catenin-induced axis formation in Xenopus embryos. Cell 1996, 86, 391–399.

- He, T.C.; Sparks, A.B.; Rago, C.; Hermeking, H.; Zawel, L.; Da Costa, L.T.; Kinzler, K.W. Identification of c-MYC as a target of the APC pathway. Science 1998, 281, 1509–1512.

- Leung, J.Y.; Kolligs, F.T.; Wu, R.; Zhai, Y.; Kuick, R.; Hanash, S.; Fearon, E.R. Activation of AXIN2 expression by β-catenin-T cell factor: A feedback repressor pathway regulating Wnt signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 21657–21665.

- Jhanwar-Uniyal, M.; Wainwright, J.V.; Mohan, A.L.; Tobias, M.E.; Murali, R.; Gandhi, C.D.; Schmidt, M.H. Diverse signaling mechanisms of mTOR complexes: mTORC1 and mTORC2 in forming a formidable relationship. Adv. Biol. Reg. 2019, 72, 51–62.

- Kim, D.H.; Sarbassov, D.D.; Ali, S.M.; King, J.E.; Latek, R.R.; Erdjument-Bromage, H.; Sabatini, D.M. mTOR interacts with raptor to form a nutrient-sensitive complex that signals to the cell growth machinery. Cell 2002, 110, 163–175.

- Haar, E.V.; Lee, S.I.; Bandhakavi, S.; Griffin, T.J.; Kim, D.H. Insulin signalling to mTOR mediated by the Akt/PKB substrate PRAS40. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007, 9, 316–323.

- Sarbassov, D.D.; Ali, S.M.; Kim, D.H.; Guertin, D.A.; Latek, R.R.; Erdjument-Bromage, H.; Sabatini, D.M. Rictor, a novel binding partner of mTOR, defines a rapamycin-insensitive and raptor-independent pathway that regulates the cytoskeleton. Curr. Biol. 2004, 14, 1296–1302.

- Pearce, L.R.; Sommer, E.M.; Sakamoto, K.; Wullschleger, S.; Alessi, D.R. Protor-1 is required for efficient mTORC2-mediated activation of SGK1 in the kidney. Biochem. J. 2011, 436, 169–179.

- Frias, M.A.; Thoreen, C.C.; Jaffe, J.D.; Schroder, W.; Sculley, T.; Carr, S.A.; Sabatini, D.M. mSin1 is necessary for Akt/PKB phosphorylation, and its isoforms define three distinct mTORC2s. Curr. Biol. 2006, 16, 1865–1870.

- De Roock, W.; Claes, B.; Bernasconi, D.; De Schutter, J.; Biesmans, B.; Fountzilas, G.; Tejpar, S. Effects of KRAS, BRAF, NRAS, and PIK3CA mutations on the efficacy of cetuximab plus chemotherapy in chemotherapy-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer: A retrospective consortium analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2010, 11, 753–762.

- Day, F.L.; Jorissen, R.N.; Lipton, L.; Mouradov, D.; Sakthianandeswaren, A.; Christie, M.; Sieber, O.M. PIK3CA and PTEN gene and exon mutation-specific clinicopathologic and molecular associations in colorectal cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 3285–3296.

- Dong, S.M.; Kim, K.M.; Kim, S.Y.; Shin, M.S.; Na, E.Y.; Lee, S.H.; Lee, J.Y. Frequent somatic mutations in serine/threonine kinase 11/Peutz-Jeghers syndrome gene in left-sided colon cancer. Cancer Res. 1998, 58, 3787–3790.

- Carpten, J.D.; Faber, A.L.; Horn, C.; Donoho, G.P.; Briggs, S.L.; Robbins, C.M.; Thomas, J.E. A transforming mutation in the pleckstrin homology domain of AKT1 in cancer. Nature 2007, 448, 439–444.

- Memmott, R.M.; Dennis, P.A. Akt-dependent and-independent mechanisms of mTOR regulation in cancer. Cell. Signal. 2009, 21, 656–664.

- Alessi, D.R.; James, S.R.; Downes, C.P.; Holmes, A.B.; Gaffney, P.R.; Reese, C.B.; Cohen, P. Characterization of a 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase which phosphorylates and activates protein kinase Bα. Curr. Biol. 1997, 7, 261–269.

- Beretta, L.; Gingras, A.C.; Svitkin, Y.V.; Hall, M.N.; Sonenberg, N. Rapamycin blocks the phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 and inhibits cap-dependent initiation of translation. EMBO J. 1996, 15, 658–664.

- Gingras, A.C.; Kennedy, S.G.; O’Leary, M.A.; Sonenberg, N.; Hay, N. 4E-BP1, a repressor of mRNA translation, is phosphorylated and inactivated by the Akt (PKB) signaling pathway. Genes Dev. 1998, 12, 502–513.

- Holz, M.K.; Ballif, B.A.; Gygi, S.P.; Blenis, J. mTOR and S6K1 mediate assembly of the translation preinitiation complex through dynamic protein interchange and ordered phosphorylation events. Cell 2005, 123, 569–580.

- Yamaguchi, K. Identification of a member of the MAPKKK family as a potential mediator of TGF-beta signal transduction. Science 1995, 270, 2008–2011.

- Cheruku, H.R.; Mohamedali, A.; Cantor, D.I.; Tan, S.H.; Nice, E.C.; Baker, M.S. Transforming growth factor-β, MAPK and Wnt signaling interactions in colorectal cancer. EuPA Open Proteom. 2015, 8, 104–115.

- Fang, J.Y.; Richardson, B.C. The MAPK signalling pathways and colorectal cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2005, 6, 322–327.

- Han, C.W.; Jeong, M.S.; Jang, S.B. Structure, signaling and the drug discovery of the Ras oncogene protein. BMB Rep. 2017, 50, 355.

- Durrant, D.E.; Morrison, D.K. Targeting the Raf kinases in human cancer: The Raf dimer dilemma. Br. J. Cancer 2018, 118, 3.

- Smalley, K.S.M. A pivotal role for ERK in the oncogenic behaviour of malignant melanoma? Int. J. Cancer 2003, 104, 527–532.

- Lavoie, J.N.; L’Allemain, G.; Brunet, A. Cyclin D1 expression is regulated positively by the p42/p44MAPK and negatively by the p38/HOGMAPK pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 20608–20616.

- Sorrentino, A.; Thakur, N.; Grimsby, S.; Marcusson, A.; Von Bulow, V.; Schuster, N.; Landström, M. The type I TGF-β receptor engages TRAF6 to activate TAK1 in a receptor kinase-independent manner. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008, 10, 1199–1207.

- Yamashita, M.; Fatyol, K.; Jin, C.; Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.E. TRAF6 mediates Smad-independent activation of JNK and p38 by TGF-β. Mol. Cell 2008, 31, 918–924.

- Sundar, R.; Gudey, S.K.; Heldin, C.H.; Landström, M. TRAF6 promotes TGFβ-induced invasion and cell-cycle regulation via Lys63-linked polyubiquitination of Lys178 in TGFβ type I receptor. Cell Cycle 2015, 14, 554–565.

- Wu, X.; Zhang, W.; Font-Burgada, J.; Palmer, T.; Hamil, A.S.; Biswas, S.K.; Karin, M. Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme Ubc13 controls breast cancer metastasis through a TAK1-p38 MAP kinase cascade. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 13870–13875.

- Comes, F.; Matrone, A.; Lastella, P.; Nico, B.; Susca, F.C.; Bagnulo, R.; Simone, C. A novel cell type-specific role of p38α in the control of autophagy and cell death in colorectal cancer cells. Cell Death Differ. 2007, 14, 693–702.

- Yang, S.Y.; Miah, A.; Sales, K.M.; Fuller, B.; Seifalian, A.M.; Winslet, M. Inhibition of the p38 MAPK pathway sensitises human colon cancer cells to 5-fluorouracil treatment. Int. J. Oncol. 2011, 38, 1695–1702.

- Slattery, M.L.; Mullany, L.E.; Wolff, R.K.; Sakoda, L.C.; Samowitz, W.S.; Herrick, J.S. The p53-signaling pathway and colorectal cancer: Interactions between downstream p53 target genes and miRNAs. Genomics 2019, 111, 762–771.

- Slattery, M.L.; Curtin, K.; Wolff, R.K.; Boucher, K.M.; Sweeney, C.; Edwards, S.; Samowitz, W. A comparison of colon and rectal somatic DNA alterations. Dis. Colon Rectum 2009, 52, 1304.

- Russo, A.; Bazan, V.; Iacopetta, B.; Kerr, D.; Soussi, T.; Gebbia, N. The TP53 colorectal cancer international collaborative study on the prognostic and predictive significance of p53 mutation: Influence of tumor site, type of mutation, and adjuvant treatment. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 7518–7528.

- Mandinova, A.; Lee, S.W. The p53 pathway as a target in cancer therapeutics: Obstacles and promise. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011, 3, 64rv1.

- Li, Q.; Lozano, G. Molecular pathways: Targeting Mdm2 and Mdm4 in cancer therapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 34–41.

- Kumar, M.; Lu, Z.; Takwi, A.A.L.; Chen, W.; Callander, N.S.; Ramos, K.S.; Li, Y. Negative regulation of the tumor suppressor p53 gene by microRNAs. Oncogene 2011, 30, 843–853.

- Ryan, K.M.; Phillips, A.C.; Vousden, K.H. Regulation and function of the p53 tumor suppressor protein. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2001, 13, 332–337.

- Shen, J.; Vakifahmetoglu, H.; Stridh, H.; Zhivotovsky, B.; Wiman, K.G. PRIMA-1MET induces mitochondrial apoptosis through activation of caspase-2. Oncogene 2008, 27, 6571–6580.

- Soleimani, A.; Rahmani, F.; Ferns, G.A.; Ryzhikov, M.; Avan, A.; Hassanian, S.M. Role of the NF-κB signaling pathway in the pathogenesis of colorectal cancer. Gene 2020, 726, 144132.

- Wong, D.; Teixeira, A.; Oikonomopoulos, S.; Humburg, P.; Lone, I.N.; Saliba, D. Extensive characterization of NF-kappaB binding uncovers non-canonical motifs and advances the interpretation of genetic functional traits. Genome Biol. 2011, 12, R70.

- Baeuerle, P.A.; Henkel, T. Function and activation of NF-kappa B in the immune system. Ann. Rev. Immunol. 1994, 12, 141–179.

- Bonizzi, G.; Karin, M. The two NF-kappaB activation pathways and their role in innate and adaptive immunity. Trends Immunol. 2004, 25, 280–288.

- Hassanzadeh, P. Colorectal cancer and NF-κB signaling pathway. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Bed Bench. 2011, 4, 127–132.

- Sakamoto, K.; Maeda, S. Targeting NF-κB for colorectal cancer. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2010, 14, 593–601.

- Evertsson, S.; Sun, X.F. Protein expression of NF-kappaB in human colorectal adenocarcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2002, 10, 547–550.

- Yang, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, M.; Qian, Y.; Dong, X.; Gu, H.; Wang, H.; Guo, S.; Hisamitsu, T. Quercetin-induced apoptosis of HT-29 colon cancer cells via inhibition of the Akt-CSN6-Myc signaling axis. Mol. Med. Rep. 2016, 14, 4559–4566.

- Refolo, M.G.; D’Alessandro, R.; Malerba, N.; Laezza, C.; Bifulco, M.; Messa, C.; Caruso, M.G.; Notarnicola, M.; Tutino, V. Anti Proliferative and Pro Apoptotic Effects of Flavonoid Quercetin Are Mediated by CB1 Receptor in Human Colon Cancer Cell Lines. J. Cell. Physiol. 2015, 230, 2973–2980.

- Raja, S.B.; Rajendiran, V.; Kasinathan, N.K.; Amrithalakshmi, P.; Venkatabalasubramanian, S.; Murali, M.R.; Devaraj, H.; Devaraj, S.N. Differential cytotoxic activity of Quercetin on colonic cancer cells depends on ROS generation through COX-2 expression. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2017, 106, 92–106.

- Shree, A.; Islam, J.; Sultana, S. Quercetin ameliorates reactive oxygen species generation, inflammation, mucus depletion, goblet disintegration, and tumor multiplicity in colon cancer: Probable role of adenomatous polyposis coli, β-catenin. Phytother. Res. 2021, 35, 2171–2184.

- Dihal, A.A.; Van der Woude, H.; Hendriksen, P.J.M.; Charif, H.; Dekker, L.J.; Ijsselstijn, L.; de Boer, V.C.J.; Alink, G.M.; Burgers, P.C.; Rietjens, I.M.C.M.; et al. Transcriptome and proteome profiling of colon mucosa from quercetin fed F344 rats point to tumor preventive mechanisms, increased mitochondrial fatty acid degradation and decreased glycolysis. Proteomics. 2008, 8, 45–61.

- Huang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Li, W.; Kong, F.; Yi, P.; Huang, J.; Zhang, S. Network pharmacology-based prediction and verification of the active ingredients and potential targets of zuojinwan for treating colorectal cancer. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2020, 14, 2725.

- Yang, Y.; Wang, T.; Chen, D.; Ma, Q.; Zheng, Y.; Liao, S.; Zhang, J. Quercetin preferentially induces apoptosis in KRAS-mutant colorectal cancer cells via JNK signaling pathways. Cell Biol. Int. 2019, 43, 117–124.

- Al-Ghamdi, M.A.; AL-Enazy, A.; Huwait, E.A.; Albukhari, A.; Harakeh, S.; Moselhy, S.S. Aumento da anexina V em resposta à combinação de galato de epigalocatequina e quercetina como uma potente parada do ciclo celular do câncer colorretal. Braz. J. Biol. 2021, 83, e248746.

- Zhang, Z.; Li, B.; Xu, P.; Yang, B. Integrated whole transcriptome profiling and bioinformatics analysis for revealing regulatory pathways associated with quercetin-induced apoptosis in HCT-116 cells. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 798.

- Catalán, M.; Ferreira, J.; Carrasco-Pozo, C. The microbiota-derived metabolite of quercetin, 3, 4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid prevents malignant transformation and mitochondrial dysfunction induced by hemin in colon cancer and normal colon epithelia cell lines. Molecules 2020, 25, 4138.

- Dihal, A.A.; de Boer, V.C.; van der Woude, H.; Tilburgs, C.; Bruijntjes, J.P.; Alink, G.M.; Stierum, R.H. Quercetin, but not its glycosidated conjugate rutin, inhibits azoxymethane-induced colorectal carcinogenesis in F344 rats. J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 2862–2867.

- Thakar, T.; Leung, W.; Nicolae, C.M. Ubiquitinated-PCNA protects replication forks from DNA2-mediated degradation by regulating Okazaki fragment maturation and chromatin assembly. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2147.

- Maga, G.; Hubscher, U. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA): A dancer with many partners. J. Cell Sci. 2003, 116, 3051–3060.

- Guo, C.; Liu, S.; Sun, M.Z. Potential role of Anxa1 in cancer. Future Oncol. 2013, 9, 1773–1793.

- Su, N.; Xu, X.-Y.; Chen, H. Increased expression of annexin A1 is correlated with K-ras mutation in colorectal cancer. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2010, 222, 243–250.

- Kim, H.S.; Wannatung, T.; Lee, S.; Yang, W.K.; Chung, S.H.; Lim, J.S.; Choe, W.; Kang, I.; Kim, S.S.; Ha, J. Quercetin enhances hypoxia-mediated apoptosis via direct inhibition of AMPK activity in HCT116 colon cancer. Apoptosis 2012, 17, 938–949.

- Li, C.; Yang, X.; Chen, C.; Cai, S.; Hu, J. Isorhamnetin suppresses colon cancer cell growth through the PI3K-Akt-mTOR pathway. Molec. Med. Rep. 2014, 9, 935–940.

- Wu, J.; Yi, J.; Wu, Y.; Chen, X.; Zeng, J.; Wu, J.; Peng, W. 3, 3′-dimethylquercetin inhibits the proliferation of human colon cancer RKO cells through Inducing G2/M cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Anti Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2019, 19, 402–409.

- Zhang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Wang, M.; Dong, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L. Quercetrin from Toona sinensis leaves induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis via enhancement of oxidative stress in human colorectal cancer SW620 cells. Oncol. Rep. 2017, 38, 3319–3326.

- Darband, S.G.; Kaviani, M.; Yousefi, B.; Sadighparvar, S.; Pakdel, F.G.; Attari, J.A.; Mohebbi, I.; Naderi, S.; Majidinia, M. Quercetin: A functional dietary flavonoid with potential chemo-preventive properties in colorectal cancer. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018, 233, 6544–6560.

- Na, S.; Ying, L.; Jun, C.; Ya, X.; Suifeng, Z.; Yuxi, H.; Jing, W.; Zonglang, L.; Xiajoun, Y.; Yue, W. Study on the molecular mechanism of nightshade in the treatment of colon cancer. Bioengineered 2022, 13, 1575–1589.

- Kee, J.Y.; Han, Y.H.; Kim, D.S.; Mun, J.G.; Park, J.; Jeong, M.Y.; Um, J.Y.; Hong, S.H. Inhibitory effect of quercetin on colorectal lung metastasis through inducing apoptosis, and suppression of metastatic ability. Phytomedicine 2016, 23, 1680–1690.

- Xavier, C.P.; Lima, C.F.; Rohde, M.; Pereira-Wilson, C. Quercetin enhances 5-fluorouracil-induced apoptosis in MSI colorectal cancer cells through p53 modulation. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2011, 68, 1449–1457.

- Zhang, X.A.; Zhang, S.; Yin, Q.; Zhang, J. Quercetin induces human colon cancer cells apoptosis by inhibiting the nuclear factor-kappa B Pathway. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2015, 11, 404–409.

- Cincin, Z.B.; Unlu, M.; Kiran, B.; Bireller, E.S.; Baran, Y.; Cakmakoglu, B. Apoptotic Effects of Quercitrin on DLD-1 Colon Cancer Cell Line. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2015, 21, 333–338.

- Kim, G.T.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, J.I.; Kim, Y.M. Quercetin regulates the sestrin 2-AMPK- p38 MAPK signaling pathway and induces apoptosis by increasing the generation of intracellular ROS in a p53-independent manner. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2014, 33, 863–869.

- Kim, G.T.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, Y.M. Quercetin Regulates Sestrin 2-AMPK-mTOR Signaling Pathway and Induces Apoptosis via Increased Intracellular ROS in HCT116 Colon Cancer Cells. J. Cancer. Prev. 2013, 18, 264–270.

- Bulzomi, P.; Galluzzo, P.; Bolli, A.; Leone, S.; Acconcia, F.; Marino, M. The pro-apoptotic effect of quercetin in cancer cell lines requires ERβ-dependent signals. J. Cell. Physiol. 2012, 227, 1891–1898.

- Banerjee, A.; Pathak, S.; Jothimani, G.; Roy, S. Antiproliferative effects of combinational therapy of Lycopodium clavatum and quercetin in colon cancer cells. J. Basic Clin. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2020, 31, 20190193.

- Lin, R.; Piao, M.; Song, Y.; Liu, C. Quercetin suppresses AOM/DSS-induced colon carcinogenesis through its anti-inflammation effects in mice. J. Immunol. Res. 2020, 2020, 9242601.

- Hashemzaei, M.; Delarami Far, A.; Yari, A.; Heravi, R.E.; Tabrizian, K.; Taghdisi, S.M.; Sadegh, S.E.; Tsarouhas, K.; Kouretas, D.; Tzanakakis, G.; et al. Anticancer and apoptosis-inducing effects of quercetin in vitro and in vivo. Oncol. Rep. 2017, 38, 819–828.

More