EVargo anvironmental problems at the global level have become a critical issue in today’s fashion industry. However, small-and medium-sized fashion business (SMFBs) encounter barriers in promoting green business owing to finances, professional expertise, knowledge, and technology. Therefore, innovative ideas are vitd Lusch (2004, 2008, 2016) developed a service-dominant logic (SDL) delineating a new service marketing theory and introduced 11 foundational premises (FPs). They noted the definition of service as the application of specialized competencies (knowledge and skills) to enhance individual benefits, processes, and performance. This definition is relevant to explaining how SDL captures resources. In SDL, operand resources are resources that produce an effect after an operation or act is performed; operand resources act on operand resources. Mainstream marketing shifts from operand resources to operant resources. Moreover, according to Lusch et al. (2007), SDL is based on understanding the interwoven fabric of individuals and organizations, brought together into networks and societies, specializing in, and exchanging the application of competencies they need for their own well-being (p. 5).

Value for SMFBs to effectively address constraints to complianceprepositions are considered to be essential premises of value co-creation.This study regard value co-creation as the upper concept relative to value prepositions and human-centered approach.

Value Proposition and the SDL

1. Human-Centered Approaches in a Field of Fashion

The human-centered approaches have promoted in-depth arguments in various studies. Sanders and Stappers (2008) defined co-creation as any act of collective creativity shared by two or more people [1]. It is generally regarded as an extremely broad term with applications ranging from the physical to the metaphysical and from the material to the spiritual [1]. Suryranna et al. (2017) posited that the development of information and communication technology rendered the co-creation of value easy for the fashion industry [2]. The researchers conducted a questionnaire survey to conduct a virtual co-creation of hijab fashion between customers and providers in Indonesia to redesign a conceptual model for virtual co-creation based on the motivation of consumers. Bujor et al. (2017) focused on the co-creation through a case study of AWAYTOMARS to identify collaborative crowdsourcing business models [3]. AWAYTOMARS is a British start-up that designs garments through co-creation on the Internet. The researchers noted that the reason for involving consumers in the process of producing new items is to listen and become closer to consumers, which creates a unique value and replaces the traditional way of thinking [3]. They argued that crowdsourcing platforms support the co-creation process and suggest the importance of an open innovation tool [3].

The next literatures of human-centered approach focus on co-design. Kwan et al. (2019) analyzed the psychological value of a co-designed footwear through workshops for older women in Hong Kong [4]. The researchers argued that using appropriate footwear can reduce the risk of falls among the geriatric population [4]. The method applied was based on a questionnaire survey that investigated the perceptions of the participants about the topic of geriatric footwear and the features of its design. Notably, the co-designed approach promoted positive psychological impacts on the elderly and influenced their acceptance of the final projects. Hur and Beverley (2019) conducted another research on co-design with a focus on fashion design [5]. The researchers explored the role of craft in a co-design system for supporting sustainable fashion design, production, and consumption, and discussed the capability of fashion designers and craft practitioners to facilitate solutions for sustainable fashion [5]. Their approaches are three-fold: conducting literature reviews to identify the key factors of non-sustainable fashion design, the implementation of the Sustainable Fashion Bridges (SFB) Ideation Toolkit, and the SFB online platform. The researchers noted the SFB toolkit facilitated the understanding and development of users and professional designers in terms of sustainable fashion design [5].

The third literatures of human-centered approach are co-production. Arvidsson and Malossi (2011) elucidated the debate around customer co-production and the consumer economy through a case of Italian fashion. They analyzed the integration of consumers into the value chains of the culture and the creative industry based on “social factor” and “brand” [6]. They noted the fashion sector represented an example of the passage from social factory to brand as modes of the integration of consumer co-production. They referred how fashion has become a core component of the cultural economy from the Renaissance to counterculture [6]. However, since the 1980s, the brands-centered experience economy came to a central stage in marketing and business practices, while the urban environment and lifestyles remains an important source of value in the forms of customer co-production [6]. Bianchini et al. (2019) noted that the maker culture of production creates opportunities for new socioeconomic, organizational, and technological models of innovation [7]. Maker spaces, living labs, and experience labs promise a future in which co-design and co-production practices are increasingly part of the innovation framework in advanced socioeconomic contexts [7]. Lodovico (2019) explored the recent development of open and collaborative fashion design practices in urban spaces and analyzed how the fab lab experience may modify the innovation process in fashion [8]. Findings showed that the approach of the fab lab to research and experiment are seemingly collaborative and open to expert and non-expert users [8]. However, the fab lab is required to cope with traditional production and academic organizations and overcome the lack of trust from potential users [8].

Another human-centered approach is co-use in terms of sharing fashion. Niinimaki (2021) noted that fashion renting and leasing services are sustainable fashion consumption options to intensify garment use and slow down material flows [9]. She described how Finland consumers converted from resistance to acceptance of sharing services [9]. She argued that social aspects of fashion leasing strengthen environmental interests and that it was active in urban contexts because the phenomenon generated a sense of belonging in local neighborhoods and communities [9]. Jain and Mishra (2020) analyzed what factors motivated Indian millennials to participate in luxury fashion rental consumption [10]. The results showed that social projection is the most significant predictor of intention to consume luxury fashion goods in a sharing economy [10]. Additionally, the researchers noted the effect of perceived risk and the influence of past sustainable behavior on young consumers’ luxury fashion rental consumption [10]. They suggested ownership-like promotion campaigns to encourage young people to shift to recycling and sustainable fashion [10].Vargo and Lusch revised the FPs in SDL in 2004, 2008, and 2016, introducing 11 FPs in the final revision and presenting the conceptual foundation for SDL axioms. In their recent revision, they pointed out the need to specify the coordination and cooperation mechanisms involved in value co-creation through the market as well as society, emphasizing both the institutional perspective of SDL and service ecosystem perspective. SDL redefines the service ecosystem as a relatively self-contained, self-adjusting resource system integrating the actors by shared institutional arrangements and mutual value creation through service exchange. Lusch and Vargo (2014) also suggested that the service ecosystem has a nested structure consisting of micro, meso, and macro systems. The different actors in the service ecosystem co-create value through interaction at various levels to create different value proposition categories. Quero and Ventura (2019) used value proposition as a framework to analyze value co-creation in Spanish business crowdfunding ecosystems. In a qualitative multiple case study, they analyzed the crowdfunding platforms in micro-, meso-, and macro-contexts to find that crowdfunding can be considered a service ecosystem once all the participants exhibit positive synergies in funding.

Lusch and Vargo (2016) presented the core concepts of SDL as follows: service is the fundamental basis of exchange (FP1), the customer is always a co-creator of value (FP6), all social and economic actors are resource integrators (FP9), value is always uniquely and phenomenologically determined by the beneficiary (FP10), and value co-creation is coordinated through actor-generated institutions and institutional arrangement (FP11). Using SDL, Mele (2009) analyzed the value innovation in business-to-business relationships in both the manufacturing and service sectors. She argued that innovations develop value propositions, which in turn provide customer service solutions through the integration of goods, services, systems, processes, and technology. However, value co-creation is coordinated through actor-generated institutions and institutional arrangements and created and determined through user consumption and the interaction of actors. Furthermore, value co-creation is created through reciprocal services based on engagement between business actors and partners.

2. Circular Fashion and Upcycling Business

Many practices related to circular fashion are based on cooperation with consumers. For example, unused clothes are collected, donated, and sold to waste operators, charity organizations, and used shops [11]. Moreover, the past few years witnessed the revival of upcycling trends in circular fashion due to pressing global environmental problems. Upcycling is a process in which used or waste products and materials are repaired, reused, repurposed, refurbished, upgraded, and remanufactured in a creative manner to add value to the compositional elements [12]. Musova et al. (2019) examined consumer attitudes toward new circular fashion models, namely, slow fashion, Global Organic Textile Standard, and jeans rental [11]. The researchers argued that consumers have exhibited the strongest motivation to buy products from waste or recycled materials. In addition, consumers prefer to support the good will of organizations [11]. Paras et al. (2019) defined upcycling as the addition of value and the formulation of viable means for reusing garments by modifying used products [13]. The researchers investigated a case study in Romania and provided practical insights into the process. Based on interview data and field observations, the conditions of the sustainability of upcycling companies were the production of regular products, and the redesign of products according to consumer needs [13]. They pointed out that upcycling businesses are generally regarded to be beset with many economic difficulties where demand-based redesign activities can contribute to the profit of organization [13]. Townsend et al. (2019) launched an upcycling education project, which was inspired by the artistic upcycled garments produced by Martin Margiela [14]. The objective of the project was to gain insights from students regarding social and sustainable issues, specifically homelessness, clothing poverty, global environmental concerns, and textile wastes [14]. In the project, the local community collects used clothing.According to Lusch and Vargo (2006), value co-creation has two components: co-creation of value and co-production. The first component is the co-creation of value. This represents the creation and generation of value through the interaction of business actors and the customer and is not the addition of value. The second component is co-production. Lusch and Vargo (2006) showed that under co-production, users collaboratively produce goods with producers, for example, through shared inventiveness, co-design, co-use, or shared production of goods through the value network. They also pointed out that co-creation is superordinate to co-production, although the concepts form a nested structured. Figure 1 presents the encompassing relationship between SDL and goods-dominant logic (GDL) as modified by Taguchi (2010).

3. Value Proposition and the SDL

Vargo and Lusch revised the FPs in SDL in 2004, 2008, and 2016, introducing 11 FPs in the final revision and presenting the conceptual foundation for SDL axioms. In their recent revision, they pointed out the need to specify the coordination and cooperation mechanisms involved in value co-creation through the market as well as society, emphasizing both the institutional perspective of SDL and service ecosystem perspective [15]. SDL redefines the service ecosystem as a relatively self-contained, self-adjusting resource system integrating the actors by shared institutional arrangements and mutual value creation through service exchange [16]. Lusch and Vargo (2014) also suggested that the service ecosystem has a nested structure consisting of micro, meso, and macro systems. The different actors in the service ecosystem co-create value through interaction at various levels to create different value proposition categories [16]. Quero and Ventura (2019) used value proposition as a framework to analyze value co-creation in Spanish business crowdfunding ecosystems [17]. In a qualitative multiple case study, they analyzed the crowdfunding platforms in micro-, meso-, and macro-contexts to find that crowdfunding can be considered a service ecosystem once all the participants exhibit positive synergies in funding [17].

Lusch and Vargo (2016) presented the core concepts of SDL as follows: service is the fundamental basis of exchange (FP1), the customer is always a co-creator of value (FP6), all social and economic actors are resource integrators (FP9), value is always uniquely and phenomenologically determined by the beneficiary (FP10), and value co-creation is coordinated through actor-generated institutions and institutional arrangement (FP11) [15]. Using SDL, Mele (2009) analyzed the value innovation in business-to-business relationships in both the manufacturing and service sectors [18]. She argued that innovations develop value propositions, which in turn provide customer service solutions through the integration of goods, services, systems, processes, and technology [18]. However, value co-creation is coordinated through actor-generated institutions and institutional arrangements [15] and created and determined through user consumption and the interaction of actors [19]. Furthermore, value co-creation is created through reciprocal services based on engagement between business actors and partners.

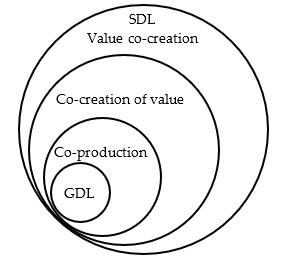

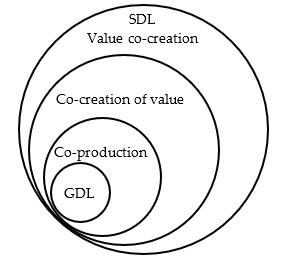

According to Lusch and Vargo (2006), value co-creation has two components: co-creation of value and co-production [19]. The first component is the co-creation of value. This represents the creation and generation of value through the interaction of business actors and the customer and is not the addition of value [19]. The second component is co-production. Lusch and Vargo (2006) showed that under co-production, users collaboratively produce goods with producers, for example, through shared inventiveness, co-design, co-use, or shared production of goods through the value network [19]. They also pointed out that co-creation is superordinate to co-production, although the concepts form a nested structured [19].

Figure 1

Outline of the Analytical Framework

This section outlines an analytical framework based on the literature reviews. This study explores how and what collaborative interactions create value propositions though value co-creation and analyzes the value propositions based on two Japanese case studies, the Onomichi Denim Project and REKROW. The study applies SDL to analyze the micro- level service ecosystem in both case studies, framing the interaction between the business actor and customer (B-C), and between the business actor and business actor (B-B) to investigate the value propositions. Additionally, Vargo and Lusch (2016) noted that the relationship between business actors in the SDL does not strictly define the producers or consumers because they engage in benefitting their own existence by benefiting other enterprises through service-for-service exchange. Thus, this study regards B-C and B-B as social and economic actors and their interaction as service-for-service exchange.

Figure 2 presents the analytical framework illustrating the concepts of value co-creation and the human-centered approach as modified by Groonroos and Voima (2013). Gronroos and Voima (2013) suggested that value creation involves a customer sphere and provider sphere. This study interprets the concept of Gronroos and Voima (2013) and adopts four human-centered approach, namely, co-design, co-creation, co-production, and co-use. In Figure 2, value in exchange is applied as service-for-service exchange for not only B-C, but also B-B. Additionally, this study regards value co-creation as the upper concept relative to human-centered approach.

Figure 2