Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Vivi Li and Version 3 by Juan Soria.

Coastal lagoons are shallow bodies of water, close to the sea, generally separated from it by a sandy bar that has produced the closure of an ancient marine gulf. They are mostly the result of the accumulation of sands and gravels of continental origin that are dragged to the coast by a river and whose accumulation is also due to the action of persistent currents.

- fishing

- pollution

- transparency

- eutrophication

- Mediterranean basin

1. Introduction

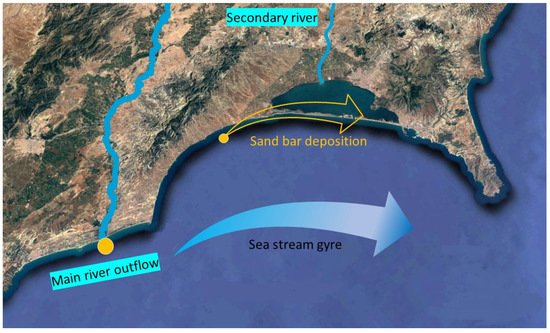

Coastal lagoons are shallow bodies of water, close to the sea, generally separated from it by a sandy bar that has produced the closure of an ancient marine gulf. They are mostly the result of the accumulation of sands and gravels of continental origin that are dragged to the coast by a river and whose accumulation is also due to the action of persistent currents. A continuous input of materials is necessary for the accumulation to occur, as well as the beach current favoring deposition in shallow areas, gulfs and inlets where there is also no major river current [1]. The balance between the contributions from its basin and its vicinity, the strength of the contributions from the interior and the accumulation by the sea are the three factors necessary for a lagoon’s formation (Figure 1). Their presence is abundant on the coasts of the Mediterranean Sea, in the Baltic Sea and in some areas of the Atlantic (France, Portugal, Morocco, Brazil, Uruguay).

Figure 1. Ideal coastal lagoon formation scheme. Base figure: Google Earth.

About seven million years ago, the movement of the tectonic plates closed the Rifian and Betic corridors (previous to the actual Gibraltar strait), so that the transfer of water was severely affected and what is known as the Miocene saline crisis occurred, with the closure of the Mediterranean Sea [2]. The sea was left as an inland sea isolated from the Atlantic and fed only by the fluvial waters of its rivers. This resulted in a drop in sea level of hundreds of meters due to evaporation and direct communication between Africa and Europe through the southern Iberian and Italian peninsula. About five million years ago, the communication with the Atlantic Ocean was opened again through the current Gibraltar corridor, and once the same water level was recovered in the two seas, the formation of the coastline began, following the approximately present line.

Therefore, the geological origin of the current coastal lagoons is recent, a few thousand years old for the most part, and they are the result of coastal dynamics. Moreover, as with many lakes, they are ephemeral formations as they are created in a few thousand years and also disappear either by siltation of the sediments that reach them or by disappearance of the sandy bar by marine erosion [3]. All the Mediterranean coastal lagoons are from the most recent Holocene period, and other sub-current lagoons are known, such as the Elx lagoon in Spain, located about 15 km from the coast, which is a remnant of the ancient Mediterranean coast prior to the Miocene saline crisis [4].

The Mediterranean coastal zones exemplify the conflict between the human exploitation of water resources and the ecological needs of aquatic ecosystems [5]. The close relationship of lagoons with terrestrial ecosystem boundaries makes these environments very vulnerable to hydrological modifications (freshwater diversions or drainage discharges), water pollution and habitat loss [6][7][8][9], which deeply change the structure of the lagoons’ ecological dynamics [10].

Coastal lagoons are a habitat declared as a priority by the European Union in the Habitats Directive, i.e., they are threatened with extinction [11]. This directive includes as coastal lagoons, in addition to those described as a typical lagoon formation, coastal evaporation salt marshes, which are also frequent on the shores of the Mediterranean. However, a hydrological distinction must be made between a coastal lagoon open to the sea and an estuary, considered as a tidal floodplain. This means that, for the purposes of the Directive, the classification of similar formations as coastal lagoons or estuaries will depend on the strength of the fluvial inputs that flow into the body of water and the influence of the tide on water renewal. This detail means that lagoons are very common in the Mediterranean due to weak tides and rivers with few contributions, while in the Atlantic the tides are higher and the rivers tend to have more contributions [12].

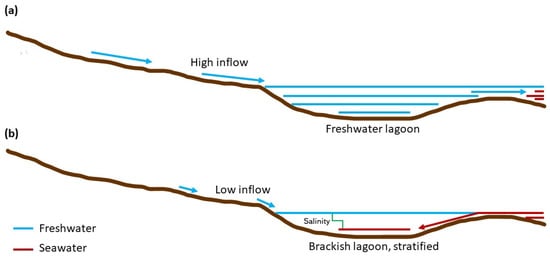

Therefore, coastal lagoons are bodies of water with scarce renewal due to low freshwater inputs and reduced communication with the sea. Their salinity is usually lower than the main sea when freshwater inputs are high and their volume is low; but this can change abruptly due to the influence of marine storms that overtake the dune bar and flood a lagoon with seawater. However, they can also be hypersaline when there is no freshwater input and the entry of seawater increases salinity by evaporation. In this sense, it can be said that they will have a positive estuarine circulation in the first case (fresh water flows out) or a negative estuary (marine water enters); they are not estuaries in any case (Figure 2) [13].

Figure 2. Water circulation models: (a) in high freshwater inflow; (b) in low inflow, with seawater entrance and high salinity lagoons.

2. Mediterranean Coastal Lagoons: Sites to Visit before Disappearance

The geographic search provided a list of thirty-seven water bodies of the minimum dimensions considered as coastal lagoons, which are listed in Table 1. Twenty-two lagoons are located on the European continent, eight on the African continent and four are in Asia, specifically in the Sinai and Anatolian Peninsulas. With regards to marine sub-basins, eight are located in the Lion Gulf, two in the Balearic Sea, three in the Alboran Sea, three in the Sicily Sea, two in the Gabès Gulf, four in the Levantine Sea, two in the Black Sea, one in the Marmara Sea, one in Aegean Sea, two in the Ionian Sea, seven in the Adriatic Sea and two in the Tyrrhenian Sea (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Location of Mediterranean Sea basins and coastal lagoons, indicating their numerical code according to Table 1. Base map source: GlobeView (https://globeview.nepia.com/, accessed on 15 January 2022).

Table 1. Location of the main coastal lagoons of the Mediterranean Sea Basin, indicating their name, numerical code (N) in Figure 3, country where they are located, sub-basin to which they belong (Sea), latitude (Lat), longitude (Long) in decimal degrees, perimeter in km, surface area in km2, maximum depth (Depth) in m and width of the opening to the sea (Open) in m.

| Name | N | Country | Sea Basin | Lat. | Long. | Perim. | Area | Depth | Open | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berre | 1 | France | Lion gulf | 43.47 | 5.10 | 67.75 | 160.03 | 9 | 105 | |||||||

| Vaccares-Monro | 2 | France | Lion gulf | 43.54 | 4.58 | 56.91 | 134.62 | 2 | 59 | |||||||

| Or | 3 | France | Lion gulf | 43.58 | 4.03 | 29.05 | 36.43 | 4 | 114 | |||||||

| Perols-Vic | 4 | France | Lion gulf | 43.49 | 3.83 | 37.85 | 33.49 | 3 | 124 | |||||||

| Thau | 5 | France | Lion gulf | 43.40 | 3.61 | 48.67 | 70.91 | 10 | 65 | |||||||

| Bages-Sigean | 6 | France | Lion gulf | 43.08 | 3.01 | 43.39 | 57.86 | 2 | 111 | |||||||

| Bages-Sigean | 6 | France | Lion gulf | 6.83 | 5.79 | 2.61 | Leucate | 7 | France | Lion gulf | 42.85 | 3.00 | 41.64 | 56.76 | 4 | 20 |

| Leucate | 7 | France | Lion gulf | 11.93 | 4.12 | 2.54 | Saint Nazaire | 8 | France | Lion gulf | 42.84 | 2.99 | 14.60 | 10.04 | 5 | 91 |

| Saint Nazaire | 8 | France | Lion gulf | 6.16 | 3.72 | 2.53 | Clot | 9 | Spain | Balearic | 40.65 | 0.66 | 17.13 | 8.63 | 1 | 46 |

| Clot | 9 | Spain | Balearic | 15.86 | 24.83 | 0.61 | Albufera | 10 | Spain | Balearic | 39.34 | −0.35 | 25.99 | 27.09 | 1 | 101 |

| Albufera | 10 | Spain | Balearic | 48.64 | 31.31 | 0.39 | La Mata-Torrevieja | 11 | Spain | Alboran | ||||||

| La Mata-Torrevieja | 11 | Spain | Alboran | 38.01 | −0.72 | 35.48 | 30.51 | 3 | 13 | |||||||

| 26.52 | 63.83 | 0.31 | Mar Menor | 12 | Spain | Alboran | 37.73 | −0.79 | 52.67 | 136.90 | 8 | 186 | ||||

| Mar Menor | 12 | Spain | Alboran | 0.85 | 1.70 | 6.50 | Marchica | 13 | Morocco | Alboran | 35.16 | −2.85 | 57.65 | 116.61 | 5 | 300 |

| Marchica | 13 | Morocco | Alboran | 1.65 | 3.24 | 3.92 | Bizerte | 14 | Tunisia | Sicily | 37.19 | 9.86 | 52.02 | 128.82 | 8 | 232 |

| Bizerte | 14 | Tunisia | Sicily | 3.60 | 4.23 | 3.44 | Ghar el Melh | 15 | Tunisia | Sicily | 37.15 | 10.18 | 25.24 | 36.39 | 2 | 74 |

| Ghar el Mehl | 15 | Tunisia | Sicily | 29.40 | 9.80 | 1.00 | Tunis | 16 | Tunisia | Sicily | 36.82 | 10.25 | 48.99 | 68.54 | 1 | 291 |

| Tunis | 16 | Tunisia | Sicily | 27.88 | 15.61 | 0.74 | Boughrara | 17 | Tunisia | Gabès gulf | 33.60 | 10.80 | 138.14 | 536.13 | 16 | 2202 |

| Boughrara | 17 | Tunisia | Gabès gulf | 3.37 | 4.36 | 2.76 | El Bibane | 18 | Tunisia | Gabès gulf | 33.25 | 11.25 | 76.65 | |||

| El Bibane | 232.97 | 5 | 914 | |||||||||||||

| 18 | Tunisia | Gabès gulf | 4.17 | 2.28 | 4.48 | Burullus | 19 | Egypt | Levantine | 30.89 | 31.48 | 124.63 | 512.98 | 2 | 80 | |

| Burullus | 19 | Egypt | Levantine | 29.43 | 30.54 | 0.45 | Manzala | 20 | Egypt | Levantine | 31.31 | 31.99 | 172.46 | 837.98 | 1 | 280 |

| Manzala | 20 | Egypt | Levantine | 32.45 | 20.21 | 0.55 | Bardawil | 21 | Egypt | Levantine | 31.15 | 33.20 | 224.43 | 626.30 | 5 | 578 |

| Bardawil | 21 | Egypt | Levantine | 38.58 | 58.80 | 0.31 | Akyatan | 22 | Turkey | Levantine | 36.63 | 35.26 | 47.43 | |||

| Akyatan | 22 | Turkey | 86.66 | 1 | 180 | |||||||||||

| Levantine | 5.32 | 4.66 | 3.01 | Karine | 23 | Turkey | Aegean | 37.59 | 27.18 | 30.88 | ||||||

| Karine | 34.58 | 1 | 680 | |||||||||||||

| 23 | Turkey | Aegean | 7.43 | 4.34 | 2.04 | Balik | 24 | Turkey | Black | 41.58 | 36.08 | 25.77 | 24.07 | 2 | 185 | |

| Razim-Sinoie | ||||||||||||||||

| Balik | 24 | Turkey | Black | 18.49 | 11.62 | 1.16 | 25 | Romania | Black | 44.80 | 29.00 | 223.72 | 1291.86 | 4 | 40 | |

| Razim-Sinoie | 25 | Romania | Black | 27.62 | 28.19 | 0.60 | Kucukcekmece | 26 | Turkey | Marmara | 41.01 | 28.75 | 24.63 | 15.22 | 20 | 25 |

| Kucukcekmece | 26 | Turkey | Marmara | 29.53 | 9.89 | 0.70 | Amvrakikos | 27 | Greece | Ionian | 38.99 | 20.92 | 168.26 | 551.95 | 58 | 590 |

| Amvrakikos | 27 | Greece | Ionian | 1.01 | 1.92 | 5.33 | Nartes | 28 | Albania | Adriatic | 40.54 | 19.43 | 33.51 | 55.40 | 1 | 60 |

| Karavasta | 29 | Albania | Adriatic | 40.93 | 19.49 | 50.79 | 82.48 | 1 | 100 | |||||||

| Marano-Grado | 30 | Italy | Adriatic | 45.74 | 13.20 | 80.11 | 160.96 | 6 | 1788 | |||||||

| Venice | 31 | Italy | Adriatic | 45.40 | 12.30 | 148.20 | 563.69 | 22 | 1730 | |||||||

| Comacchio | 32 | Italy | Adriatic | 44.60 | 12.18 | 51.79 | 147.53 | 2 | 48 | |||||||

| Lesina | 33 | Italy | Adriatic | 41.88 | 15.45 | 52.23 | 51.01 | 3 | 27 | |||||||

| Varano | 34 | Italy | Adriatic | 41.88 | 15.74 | 34.97 | 65.52 | 1 | 56 | |||||||

| Mare Piccolo | 35 | Italy | Ionian | 40.48 | 17.28 | 25.17 | 21.20 | 13 | 142 | |||||||

| Orbetello | 36 | Italy | Tyrrhenian | 42.45 | 11.21 | 42.64 | 33.47 | 1 | 70 | |||||||

| Cabras | 37 | Italy | Tyrrhenian | 39.94 | 8.48 | 33.75 | 23.66 | 2 | 204 |

In six cases, the lagoonal water body is geographically divided into two lagoons very close to each other, so that for the purposes of this entry it is considered as one water body with two lagoons, each with its own name. This is the case, for example, of the Vaccarès and Monro lagoons (number 2) in France [14] or the Marano and Grado lagoons (number 30) in Italy [15].

Most lagoons are related to the presence of a deltaic river formation, such as the deltas of the Rhone, Ebro, Jucar, Segura, Moulouya, Nile, Danube and Po rivers. Some other lagoons have their origin in the movement of sands by marine currents, with the origin of materials from other places, such as the lagoons of Tunisia and those of Italy, whose formation is due to coastal morphology, without the presence of a river with deltaic formation. Figure 3 shows the location of the studied lagoons on the Mediterranean coast.

As for their characteristics, the coastal lagoons are mostly shallow, with maximum depths of up to ten meters, except those where the connection with the sea is open and are used for navigation, so they have up to 58 m as the deepest value [16] in the case of the Gulf of Amvrakikos (number 27). The maximum extension is presented in the Razim-Sinoie lagoon (number 25), located in the Danube delta [17], with an area of 1292 km2. However, the longest is the Bardawil lagoon (number 21) located in the Nile delta [18], with 33.2 km on its longest axis.

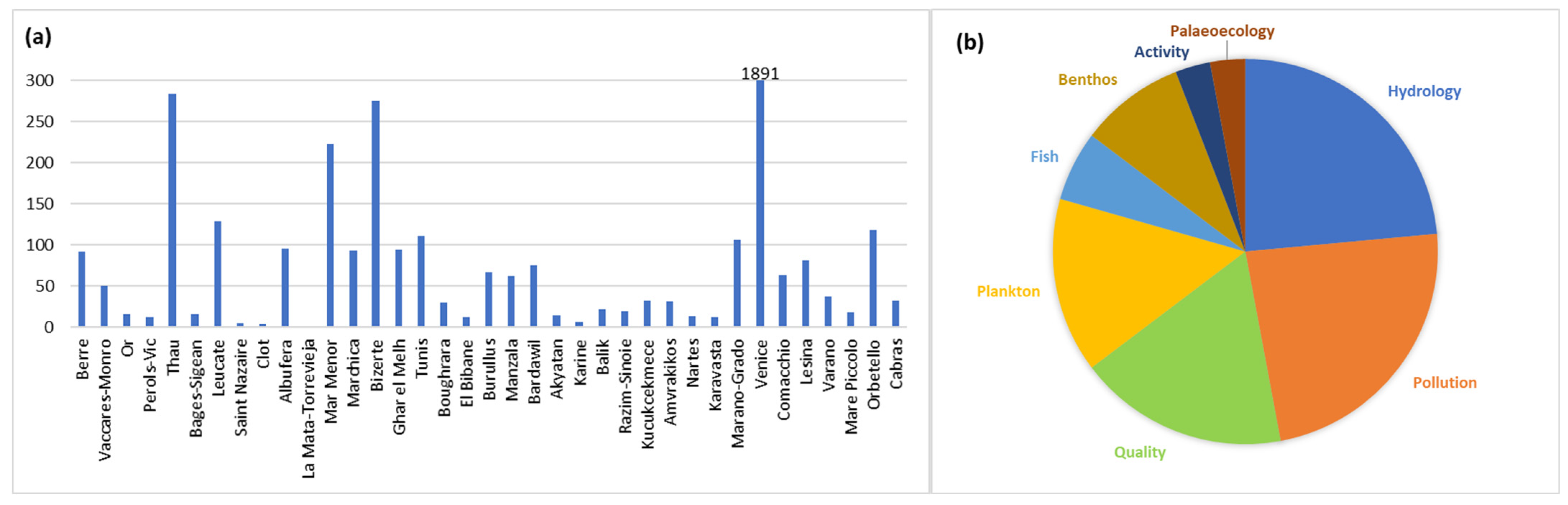

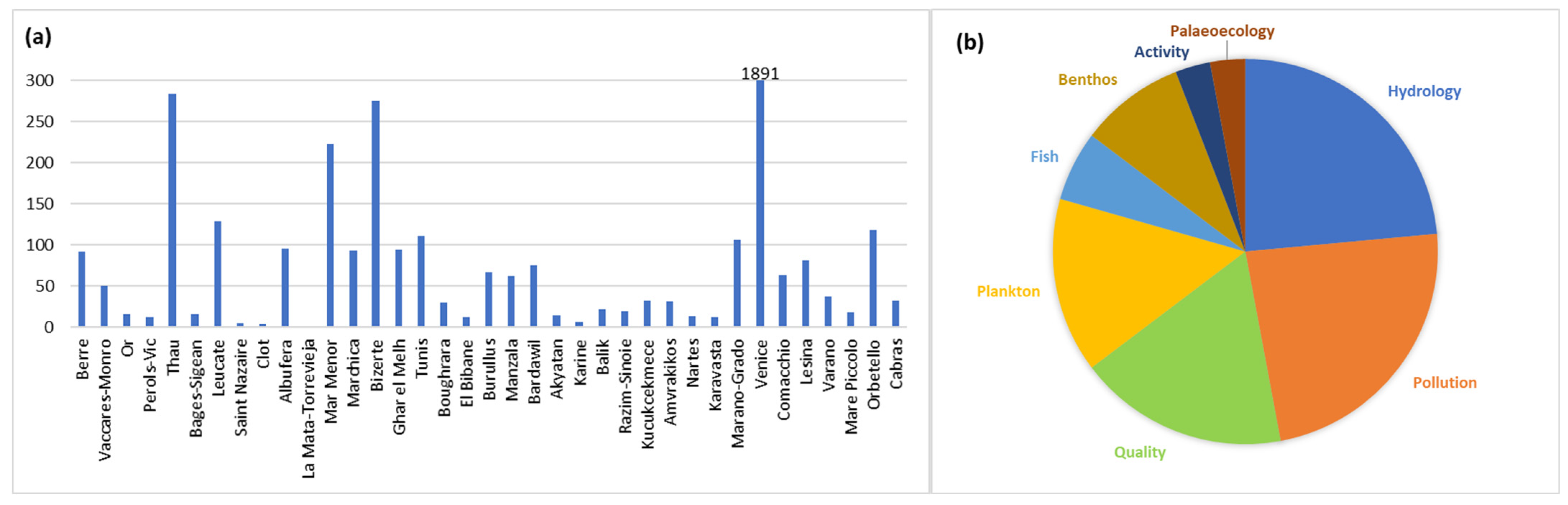

The bibliographic review has shown that the most studied are the Venice lagoon [19] (more than 1800 publications) and the Mar Menor (about 300) [20]. At a lower level, the lagoons of Thau, Leucate, Bizerte, Tunis, Marano-Grado and Orbetello already have between 300 and 100 publications (Figure 4a) [15][21][22][23][24][25].

Figure 4. (a) Number of scientific publications indexed on each of the Mediterranean coastal lagoons. (b) Scope of the recent papers from 2016 to 2021 published in each lagoon.

Of the most recent published papers, the main topics are related to hydrology, pollution and water quality (Figure 4b), while the remaining third of the publications are related to plankton, fish, sediment and benthos, economic activities and paleoecology.

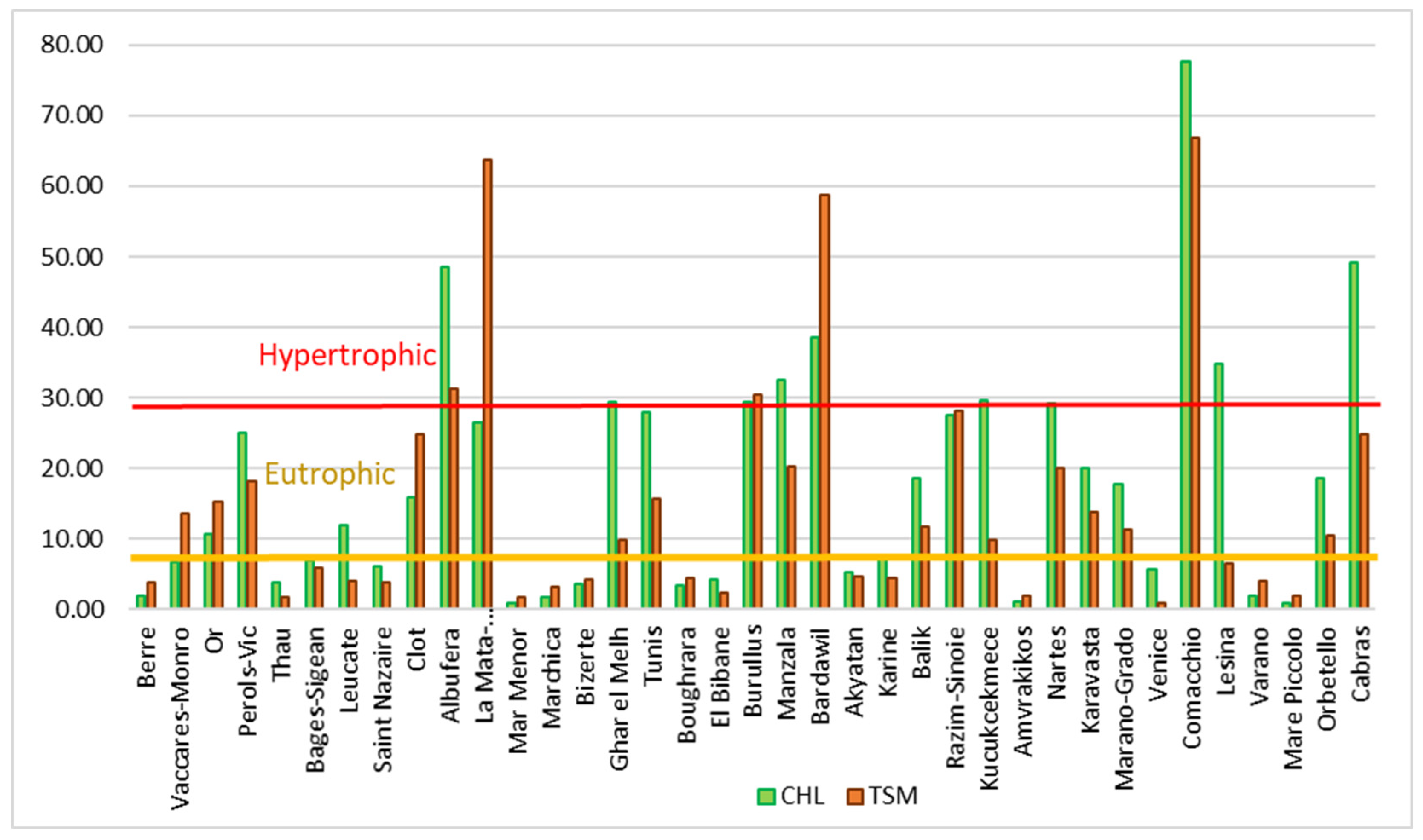

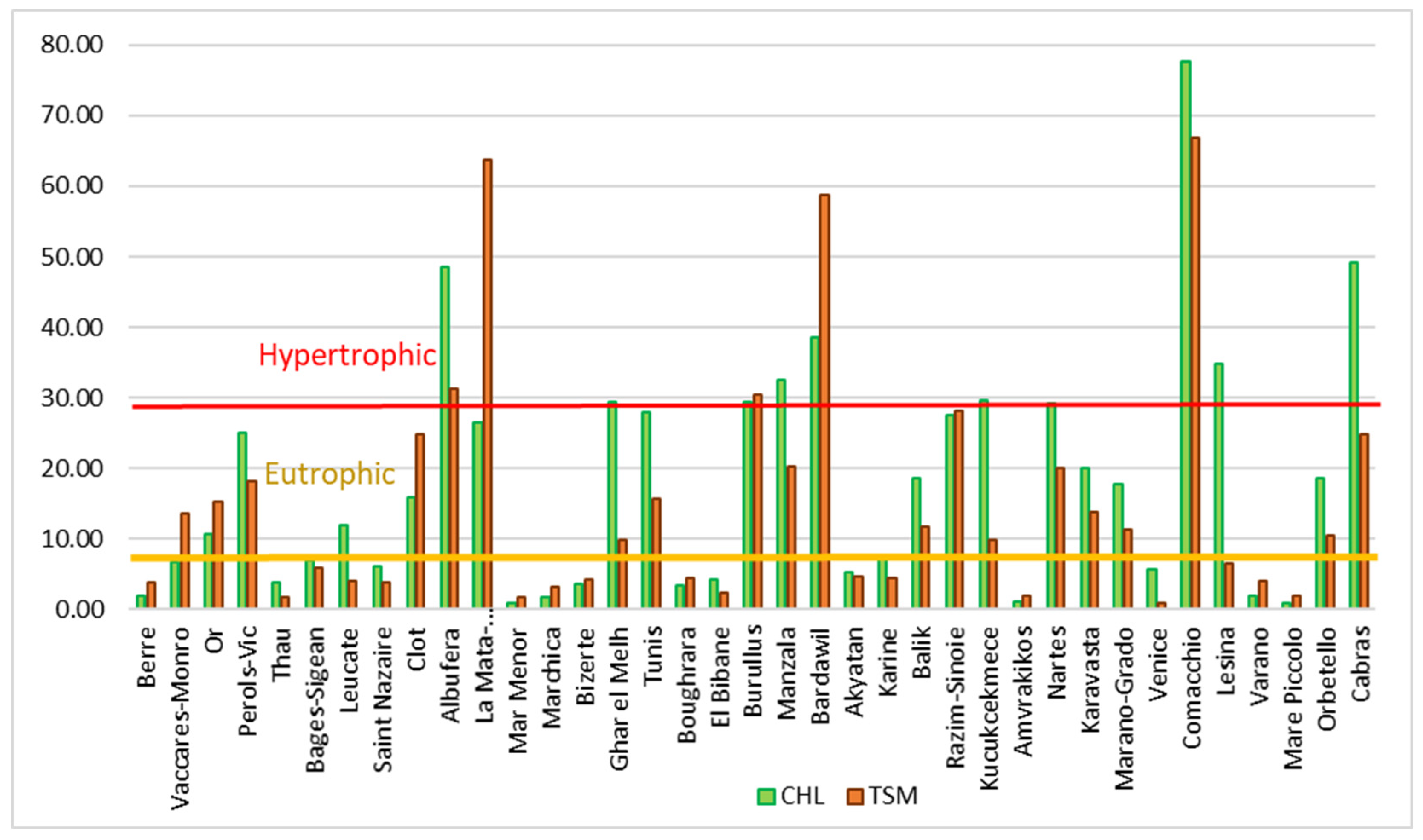

Regarding the trophic state, the results obtained (Table A1) indicate that the lagoons are generally in a poor trophic state (Figure 5). From the chlorophyll a content, applying the trophic state ranges defined by Carlson and Havens [26], eight lagoons are eutrophic (chlorophyll concentration between 8 and 25 µg/L) and 13 exceed this value, being classified as hypertrophic. Ten of them are mesotrophic and only six are in a good trophic state, with a chlorophyll a value of less than 2 µg/L: Berre (France), Mar Menor in Spain, Marchica (Morocco), Amvrakikos in Greece and Varano and Mare Piccolo in Italy. These are characterized by a good openness to the sea (except Varano). One might think that those lagoons with good communication with the sea are in a better condition than those with more limited communication, but it is clear that the pressures of the environment are more important [6][13].

Figure 5. Trophic status of coastal lagoons assessed by chlorophyll a concentration in summer 2020. Chlorophyll a concentration (CHL) in mg/m3 and TSM concentration in mg/L.

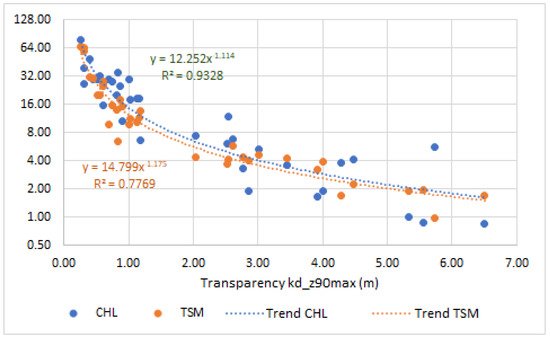

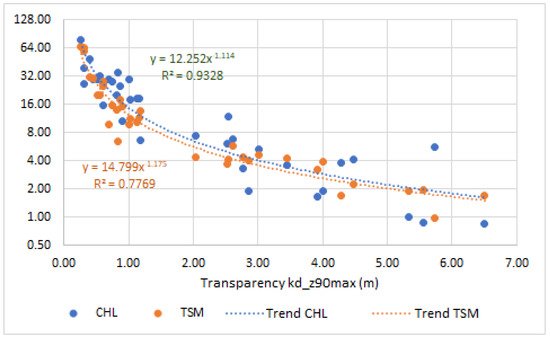

There is a significant statistical correlation between water transparency, measured as coefficient kd_z90max, and CHL and TSM concentration, in both cases p < 0.001, but the coefficient of determination is much higher for CHL than for TSM. High transparency values of water are correlated with low values of phytoplankton and suspended matter in the water (which can be biological or inert material). Figure 6 shows the distribution of the values of both variables.

Figure 6. Representation of water transparency values (kd_z90max) versus chlorophyll a concentration in mg/m3 (CHL) and suspended matter in mg/L (TSM). For each variable, the trend line, the adjust equation and its coefficient of determination are represented.

Ecologically, their importance lies in the fact that they are fluctuating environments, where aquatic vegetation of interest such as Ruppietea maritimae, Potametea, Zosteretea or Charetea associations develop [27]. The variation in salinity favors the presence of certain catadromous species of fish, so the use of these bodies of water for fishing by humans is historical. It is curious that the fishing systems used in the Mediterranean are similar in both Europe and Africa, performing set-ups with palisades and fixed nets that lead to the displacement of fish to the point where they are caught by the capture and extraction nets. From the aerial images it can be seen that in all locations the set-up is similar (Figure 7). It has been shown from research that the fishing system is of Phoenician origin, and that is why it has been widespread throughout the Mediterranean for more than 2000 years. However, for Steinberg [28], the system was already in use about 4500 years ago in Denmark (Figure 7d).

Figure 7. Current fishing set-up systems used in Mesopotamia in various coastal lagoons: (a) Redolín in Albufera de Valencia (Spain) March 2020. (b) Charfia in El Bibane (Tunisia). (c) Encañizada in Mar Menor (Spain) March 2017 (Archive of Murcia County Government). (d) Reconstruction of a fish hedge from Oleslyst, Denmark, about 4500 years old, sketch traced by J.S. [28].

Beyond the environmental value of these treats, the cultural and scenic value of the coastal lagoons is recognized by the citizens of the surrounding area [29]. First of all, by the fishing exploitation of local communities since historical times [10][30], and also the scenery of the water from the shore, in conjunction with the visualization of the environment, makes it highly appreciated, not only for the richness in species, but also for the visualization of the sunrise or sunset. In many lagoons there are a large number of landscapes related to this spiritual appreciation (Figure 8). Table A2 in the annex presents a list of the existing environmental protection figures as well as the tourist values that are of cultural interest.

Figure 8. Sunset in some lagoons: (a) Bardawil, (b) Venice, (c) Razim-Sinoie. Source: Google Photos.

Appendix A

Table A1. Variables obtained by studying Sentinel-2 imagery in summer 2020. CHL-a, chlorophyll a (mg/m3); TSM, total suspended matter (mg/L); Kd_z90max, water transparency measured as depth at which 10% of incident light reaches the surface (m). Highlighted in green, lagoons in better ecological status; in orange, lagoons in worse ecological status.

| Name | Number | Country | Sea | CHL-a | TSM | Kd_z90max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berre | 1 | France | Lion gulf | 1.91 | 3.88 | 4.01 |

| Vaccares-Monro | 2 | France | Lion gulf | 6.65 | 13.60 | 1.19 |

| Or | 3 | France | Lion gulf | 10.71 | 15.33 | 0.90 |

| Perols-Vic | 4 | France | Lion gulf | 25.02 | 18.12 | 0.86 |

| Thau | 5 | France | Lion gulf | 3.82 | 1.71 | 4.28 |

| Nartes | ||||||

| 28 | ||||||

| Albania | ||||||

| Adriatic | ||||||

| 29.26 | ||||||

| 20.08 | ||||||

| 0.52 | ||||||

| Karavasta | ||||||

| 29 | ||||||

| Albania | ||||||

| Adriatic | ||||||

| 19.99 | 13.87 | 0.81 | ||||

| Marano-Grado | 30 | Italy | Adriatic | 17.81 | 11.31 | 1.03 |

| Venice | 31 | Italy | Adriatic | 5.70 | 0.98 | 5.73 |

| Comacchio | 32 | Italy | Adriatic | 77.69 | 66.84 | 0.26 |

| Lesina | 33 | Italy | Adriatic | 34.75 | 6.53 | 0.84 |

| Varano | 34 | Italy | Adriatic | 1.93 | 4.02 | 2.86 |

| Mare Piccolo | 35 | Italy | Ionian | 0.87 | 1.98 | 5.55 |

| Orbetello | 36 | Italy | Tyrrhenian | 18.61 | 10.48 | 1.13 |

| Cabras | 37 | Italy | Tyrrhenian | 49.22 | 24.80 | 0.41 |

Table A2. Aspects of interest in the studied lagoons related to biodiversity, tourist interest, gastronomy and protection figures.

| Country | Name | Sea | Biodiversity | Tourism Interest | Gastronomy | Protection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| France | Vaccares-Monro | Lion gulf | There are 65% unique species in the area (flora and fauna) | City of Marseille, medieval towns and Avignon | Vineyards, wines of Luberon, olive oil, lavender oil, and cheeses | Ramsar site. Natura 2000. Department of Bouches-du-Rhone. Provence natural parks. |

| Le Berre | ||||||

| Thau | ||||||

| Pérols-Vic | Montpellier was chosen as the capital of French biodiversity | City of Montpellier, the folies (ancient palaces), the region of Languedoc-Rousillion | Wines, seafood and bull meat | Ramsar site. Natura 2000. Green Net (2007) which cares about studies of environmental impact. |

||

| L’Or | ||||||

| Leucate | In this county, there is one of the largest natural reserve of France. | Beaches, lagoons, vineyards | Seafood and steakhouses | Ramsar site. Natura 2000. |

||

| Bages-Sigean | ||||||

| Saint Nazaire | ||||||

| Spain | Clot | Balearic | Habitat of 280 species of birds | Cities of Tarragona and Valencia, medieval towns, beaches | Seafood, paella, duck rice, “l’espardenyà” | Ramsar site. Natura 2000. Natural parks. |

| Albufera | ||||||

| La Mata-Torrevieja | Alboran | Rich zone of biodiversity of marine and terrestrial species. Some are endemic and of great biological interest. |

Cities of Alacant and Murcia, some popular towns, beaches | Michelin restaurants, seafood, mojama | Ramsar site. Natura 2000. Natural parks. |

|

| Mar Menor | ||||||

| Morocco | Marchica | Alboran | Flamingo bay, birds shelter | Resorts, golf course, cities of Nador and Melilla | Tajine, couscous, Khubz bread, hummus | Ramsar site. Institut National de Recherche Halieutique-Centre de Nador (University of Mohammed V) |

| Tunisia | Bizerte | Sicily | Ichkeul Natural Park (nature reserved named World Heritage by UNESO). | Qsiba, Ichkeul National Park, Utica, ottoman fortresses | Seafood, chakchouka, couscous, jelbana, kefteji | Ramsar site. National Tourism Organization |

| Ghar el Mehl | ||||||

| Tunis | ||||||

| Boughrara | Gabès gulf | |||||

| El Bibane | ||||||

| Manzala | ||||||

| Bardawil | ||||||

| Egypt | Burullus | Levantine | 135 endemic plants, dunes, natural reserves | Cities of El Cairo and Alexandria | Ful Medames, Koshari, Baba Ganoush, Fatteh, Kofta, falafel | Ramsar site. |

| Manzala | ||||||

| Bardawil | ||||||

| Turkey | Akyatan | Levantine | Important Bird Area | Adana, Mersin, ottoman castles | Ayran, Raki, Kahve, baklava, Turkish delicacies | Ramsar site. Natural Park |

| Karine | Aegean | Aquatic birds | Buyuk delta | |||

| Balik | Black | Birds, velvet duck | Estambul, Ankara | |||

| Kucukcekmece | Ionian | |||||

| Romania | Razim-Sinoie | Black | Birds and fishes | Museum of Ebisala, Istria, Aerganum fortresses, Sarichioi and Jurilovca towns | Ciorba de burta, Zacusca, Mici, sarmale | Ramsar site. World heritage site. UNESCO Biosphere Reserve |

| Greece | Amvrakikos | Ionian | Marshes, endemic flora and bids fauna | Arta, byzantine fortresses, island of Koronisia | Moussaka, tzatziki, gyros, fava | Ramsar site. Natura 2000. |

| Albania | Karavasta | Adriatic | Birds protection | Byzantine art | Fish and eels | Ramsar site. National Park. |

| Nartes | ||||||

| Italy | Marano-Grado | Adriatic | High biodiversity and there are a lot of marine regions protected. Endemic Flora. Fauna there are swans, dophins, friar seal or flamingos |

Venice, Murano, Bolonia, Ferrera, Verona. Cultural heritage. |

Pasta, pizza, wine, tiramisu, risotto, carpaccio, calzone | Natura 2000. Ramsar site.Protected by the statal government and UNESCO |

| Venice | ||||||

| Comacchio | ||||||

| Lesina | ||||||

| Varano | ||||||

| Mare Piccolo | Ionian | Tarento, churches | ||||

| Orbetello | Tyrrhenian | Toscana, Porto Ercole and Porto Santo Stefano | ||||

| Cabras | Sardinia | Historic place | Sardinia island | |||

References

- Cañedo-Argüelles, M.; Rieradevall, M.; Farrés-Corell, R.; Newton, A. Annual characterisation of four Mediterranean coastal lagoons subjected to intense human activity. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2012, 114, 59–69.

- Blanc, P.L. Improved modelling of the Messinian Salinity Crisis and conceptual implications. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclim. Palaeoecol. 2006, 238, 349–372.

- De Wit, R. Biodiversity of coastal lagoon ecosystems and their vulnerability to global change. In Ecosystems Biodiversity; Grillo, O., Venore, G., Eds.; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2011; pp. 29–40.

- Sanjaume, E.; Pardo-Pascual, J.E.; Segura-Beltran, F. Mediterranean Coastal Lagoons. In The Spanish Coastal Systems; Morales, J., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019.

- Flower, R.J.; Thompson, J.R. An overview of integrated hydro-ecological studies in the MELMARINA Project: Monitoring and modelling coastal lagoons—making management tools for aquatic resources in North Africa. Hydrobiologia 2009, 622, 3–14.

- Gamito, S.; Gilabert, J.; Marcos, C.; Perez Ruzafa, A. Effects on changing environmental conditions on lagoon ecology. In Coastal Lagoons: Ecosystem Processes and Modeling for Sustainable Use and Development; Gönenç, I.E., Wolflin, J.P., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005; pp. 193–229.

- Pérez-Ruzafa, A.; Navarro, S.; Barba, A.; Marcos, C.; Camara, M.; Salas, F.; Gutierrez, J.M. Presence of pesticides throughout trophic compartments of the food web in the Mar Menor lagoon. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2000, 40, 140–151.

- Pérez-Ruzafa, A.; Gilabert, J.; Gutiérrez, J.M.; Fernández, A.I.; Marcos, C.; Sabah, S. Evidence of a planktonic food web response to changes in nutrient input dynamics in the Mar Menor coastal lagoon, Spain. In Nutrients and Eutrophication in Estuaries and Coastal Waters. Developments in Hydrobiology; Orive, E., Elliott, M., de Jonge, V.N., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2002; Volume 164, pp. 359–369.

- Pérez-Ruzafa, A.; Marcos, C.; Gilabert, J. The ecology of the Mar Menor coastal lagoon: A fast-changing ecosystem under human pressure. In Coastal Lagoons: Ecosystem Processes and Modeling for Sustainable Use and Development; Gönenç, I.E., Wolflin, J.P., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005; pp. 392–422.

- Cataudella, S.; Crosetti, D.; Massa, F. Mediterranean coastal lagoons: Sustainable management and interactions among aquaculture, capture fisheries and the environment. Gen. Fish. Comm. Mediterranean. Stud. Rev. 2015, 95, 278.

- European Union. Habitats Directive, Council Directive 92/43/EEC of 21 May 1992 on the conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora. Off. J. Eur. Union 1992, 206, 7–50.

- Soria, J.; Vera-Herrera, L.; Calvo, S.; Romo, S.; Vicente, E.; Sahuquillo, M.; Sòria-Perpinyà, X. Residence Time Analysis in the Albufera of Valencia, a Mediterranean Coastal Lagoon, Spain. Hydrology 2021, 8, 37.

- Kjerfve, B. Coastal Lagoons. In Coastal Lagoon Processes; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1994.

- Boutron, O.; Paugam, C.; Luna-Laurent, E.; Chauvelon, P.; Sous, D.; Rey, V.; Meulé, S.; Chérain, Y.; Cheiron, A.; Migne, E. Hydro-Saline Dynamics of a Shallow Mediterranean Coastal Lagoon: Complementary Information from Short and Long Term Monitoring. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 701.

- Marano Bettoso, N.; Aleffi, I.F.; Faresi, L.; D’Aietti, A.; Acquavita, A. Macrozoobenthos monitoring in relation to dredged sediment disposal: The case of the Marano and Grado lagoon (northern Adriatic Sea, Italy). Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2020, 33, 100916.

- Vasileiadou, K.; Pavloudi, C.; Kalantzi, I.; Apostolaki, E.T.; Chatzigeorgiou, G.; Chatzinikolaou, E.; Pafilis, E.; Papageorgiou, N.; Fanini, L.; Konstas, S.; et al. Environmental variability and heavy metal concentrations from five lagoons in the Ionian Sea (Amvrakikos gulf, W Greece). Biodivers. Data J. 2016, 4, e8233.

- Catianis, I.; Secrieru, D.; Pojar, I.; Grosu, D.; Scrieciu, A.; Pavel, A.B.; Vasiliu, D. Water quality, sediment characteristics and benthic status of the Razim-Sinoie Lagoon System, Romania. Open Geosci. 2018, 10, 12–33.

- Elshinnawy, I.A.; Almaliki, A.H. Al Bardawil Lagoon Hydrological Characteristics. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7392.

- Mel, R.A.; Carniello, L.; D’Alpaos, L. How long the MO.S.E. barriers will be effective in protecting all urban settlements within the Venice lagoon? the wind setup constraint. Coast. Eng. 2021, 168, 103923.

- Alcon, F.; Miguel, M.D.; Martínez-Paz, J.M. Assessment of real and perceived cost-effectiveness to inform agricultural diffuse pollution mitigation policies. Land Use Policy 2021, 107, 104561.

- Courboulès, J.; Vidussi, F.; Soulié, T.; Mas, S.; Pecqueur, D.; Mostajir, B. Effects of experimental warming on small phytoplankton, bacteria and viruses in autumn in the mediterranean coastal Thau lagoon. Aquat. Ecol. 2021, 55, 647–666.

- Elineau, S.; Longépée, E.; Goeldner-Gianella, L.; Nicolae-Lerma, A.; Durand, P.; Anselme, B. Understanding coastal flood risk prevention by combining modelling and sketch maps (Mediterranean coast, France). Environ. Hazards 2020, 20, 457–476.

- El Zrelli, R.; Yacoubi, L.; Wakkaf, T.; Castet, S.; Grégoire, M.; Mansour, L.; Courjault-Radé, P.; Rabaoui, L. Surface sediment enrichment with trace metals in a heavily human-impacted lagoon (Bizerte lagoon, southern Mediterranean Sea): Spatial distribution, ecological risk assessment, and implications for environmental protection. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 169, 112512.

- Abidi, M.; Ben Amor, R.; Gueddari, M. Sedimentary dynamics of the south lagoon of Tunis (Tunisia, Mediterranean Sea). Est. Geol. 2019, 75, 86.

- Romano, E.; Bergamin, L.; Croudace, I.W.; Ausili, A.; Maggi, C.; Gabellini, M. Establishing geochemical background levels of selected trace elements in areas having geochemical anomalies: The case study of the Orbetello lagoon (Tuscany, Italy). Environ. Pollut. 2015, 202, 96–103.

- Carlson., R.E.; Havens, K.E. Simple Graphical Methods for the Interpretation of Relationships Between Trophic State Variables. Lake Reserv. Manag. 2005, 21, 107–118.

- European Commission. Interpretation Manual of European Union Habitats. D.G. Environment, Nature ENV B.3. 2013, p. 148. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/legislation/habitatsdirective/docs/Int_Manual_EU28.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Fischer, A. Coastal fishing in Stone Age Denmark–evidence from below and above the present sea level and from human bones. In Shell Middens and Coastal Resources along the Atlantic Façade; Milner, N., Bailey, G., Craig, O., Eds.; Oxbow: Oxford, UK, 2007; Volume 3, pp. 54–69.

- Moreno, J.M.; López-Ortiz, M.I. From industrial activity to cultural and environmental heritage: The Torrevieja and La Mata lagoons (Alicante). Bol. De La Asoc. De Geogr. Españoles 2008, 47, 311–331.

- Pauly, D.; Yáñez-Arancibia, A. Fisheries in coastal lagoons. In Elsevier Oceanography Series; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1999; Volume 60, pp. 377–399.

More