You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Vicky Zhou and Version 1 by Sascha Venturelli.

Minerals and trace elements are important micronutrients for normal physiological function of the body. They are abundant in natural food sources and are regularly included in dietary supplements whereas highly processed industrial food often contains reduced or altered amounts of them. In modern society, the daily intake, storage pools, and homeostasis of these micronutrients are dependent on certain dietary habits and can be thrown out of balance by malignancies. Their dietary imbalance, which is becoming more common in the diets of industrialized countries, is linked to an increased risk of cancer.

- cancer

- biomarkers

- minerals

- copper

- zinc

- selenium

- iron

- iodine

- phosphorus

- calcium

1. Introduction

After World War Two, the mean food intake increased drastically, reflected in an ongoing obesity epidemic [1,2][1][2]. On the other hand, the quality of the food did not. Specifically, there has been a decrease in several minerals in foods over the last five decades, most notably zinc, copper, and iron [3,4,5][3][4][5]. Such an occurrence is mirrored in the worldwide spread of “hidden hunger”, defined as a prolonged lack of vitamins or minerals (collectively referred to as micronutrients) intake [6,7][6][7]. For example, it has been estimated that the daily intake of selenium is half that of the reference nutrient intake [8].

Micronutrients are necessary for immunological functions as well as the general cellular metabolism [9]. For instance, it has been shown that deficiency in micronutrients, including minerals, worsens the pathogenesis of COVID-19 [10]. Moreover, given the link between an abnormal immune system and oncogenesis [11], identifying factors that affect the former can aid in predicting the latter. Quantification of biomolecules that can interfere with immune function, for example, could theoretically serve as an indicator for cancer risk. Micronutrients in general and minerals, in particular, are suitable for this purpose.

Given that cellular biochemistry requires micronutrients, the ongoing and unnoticed subclinical deficiency of micronutrients might cause significant global health issues. In particular, the hidden hunger might increase the risk of cancer development. Consequently, the measurement of micronutrients in general and minerals, in particular, might help the early identification of people at higher cancer risk.

The recommended daily intake and associated serum levels of the most common minerals are summarized in Table 1 and serve as the basis for the categorization of the minerals referred to.

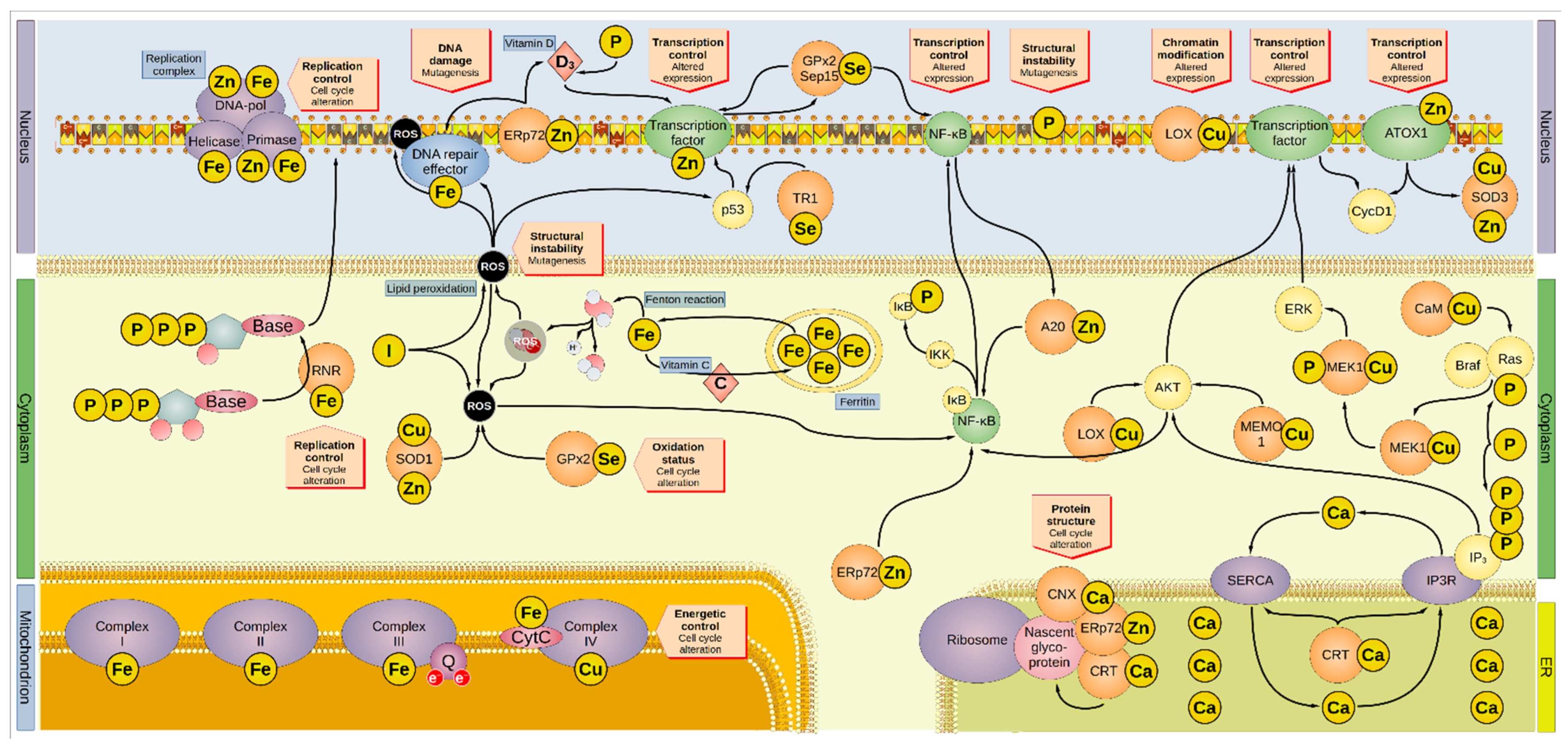

Figure 1. Overview of the involvement of minerals in oncogenesis. Minerals are involved in several and overlapping cellular pathways. Iron is sequestered by ferritin inside the cytoplasm. Iron leaking from the ferritin cages can react with water to form hydroxyl radical, one of the many ROS. Vitamin C promotes the reload of iron inside the ferritin cages. ROS can interact with lipid bilayers, generating more ROS molecules by lipid peroxidation, a process inhibited by iodide. In addition, ROS can directly damage the DNA and proteins, including the DNA-repair enzymes that are activated by ROS-induced damage. Furthermore, ROS activates p53 and NF-κB, altering the cell cycle. Iodide, SOD1, and GPx2 inactivate ROS. For instance, SOD1 removes superoxide radicals by dismutation reaction generating H2O2, O2, and GPx2 by producing two H2O from auto-reduction. The DNA-repair factors are modulated by the zinc-protein ERp72, which regulates the intake of vitamin D involved in the regulation of transcriptional factors. Cellular intake of vitamin D is also regulated by phosphorus. ERp72 reduces disulfide bonds in nascent proteins in the ER, in association with the calcium-proteins CNX and CRT. Moreover, ERp72 regulates NF-κB, the latter being also modulated by GPx2 and Sep15. GPx2 and Sep15 promote their own expression. A20 and AKT also activate NF-κB, which then reduces the activity of A20 in a negative feedback loop. AKT is modulated by LOX, MEMO1, and IP3, and affects the cell cycle by promoting the expression of CycD1. LOX can alter genetic expression by modifying the histones. Some transcription factors contain zinc, and a transcription regulator is p53, which TR1 modulates. ATOX1 is a zinc-containing protein that can modulate gene expression, particularly that of cyclin D1 and SOD3 (which regulate the oxidative environment outside the cell). Genetic transcription and cell cycle are regulated by ERK, which MEK1 activates after being phosphorylated by the complex Ras/Braf. One of the modulators of Ras is CaM, but also phosphorus can directly boost its activation. Similarly, phosphorus is also part of active IP3 that, aside from its direct modulation of AKT, regulates the release of calcium (effectively a second messenger on its own right) from the ER via the Ca2+ channel IP3R. The P-type ATPase SERCA mediates the transport of cytosolic calcium back into the ER. CRT regulates both IP3R and SERCA. Moreover, minerals are involved in DNA replication since they are embedded in several subunits of the DNA replication complex (namely: iron in the helicase, primase, and DNA-polymerase α, the latter two also containing zinc). Iron is present in the first three mitochondrial complexes and CytC, whereas copper is present in complex IV. Thus, minerals are essential to the energetic balance of the cell and its oxidative state. AKT, Ak strain transforming; A20, zinc finger protein A20; ATOX1, antioxidant-1; Braf, rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma isoform B; CaM, calmodulin; CNX, calnexin; CRT, calreticulin; CycD1, cyclin D1; CytC, cytochrome c; DNA-pol, DNA polymerase; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; Erp72, endoplasmic reticulum resident protein 72; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; GPx2, glutathione peroxidase 2; IκB, NF-κB inhibitor; IKK, IκB kinase; IP3, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate; IP3R, inositol trisphosphate receptor; LOX, lysyl oxidase; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; MEK1, MAPK/ERK kinase1; MEMO1, mediator of cell motility 1; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; Q, coenzyme Q; Ras, rat sarcoma virus; RNR, ribonucleotide reductase; ROS, reactive oxygen species; Sep15, selenoprotein of 15-kDa; SERCA, sarco-/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase; SOD, superoxide dismutase; TR1, thioredoxin reductase 1.

Table 1. Recommended daily intakes and related serum levels of the minerals reported her *.

| Mineral | RDA/PRI (µg/Day) |

EAR/AR (µg/Day) |

UL (µg/Day) |

Serum Levels | Source | References |

|---|

Table 3. Summary of the mineral levels in the studies retrieved here.

* Depicted data refers to male adults. AR: average requirement; EAR: estimated average requirement; n.d.: not determined by EFSA; PRI: population reference intake; RDA: recommended daily allowance; UL: tolerable upper intake level. † as ferritin. ‡ not reliable indicator for zinc status.

2. Minerals and Risk of Cancer

Nutrition’s role in oncogenesis is increasingly being researched and supported by new scientific data. As a result, scientists are becoming more and more interested in determining the role of micronutrients in DNA stability, epigenetic regulation, immunological response, and in assessing their role as biomarkers.

Tumorigenesis is extremely complex and varies greatly between tumor entities due to the involvement of multiple molecular processes. The present analysis revealed some intriguing tendencies, even though there is no unified trend relating mineral intake and cancer risk. Specifically, higher levels of copper, iron, and iodine were linked to higher cancer risk, but zinc, selenium, calcium, and phosphorus had a more mixed relationship. A higher mineral intake was linked to an increased risk of oral cancer (iron, selenium, phosphorus, and zinc). Higher levels of zinc and copper, but lower levels of selenium, were more associated with liver cancer. Prostate cancer, on the other hand, was associated with higher phosphorus intake. The association between minerals and risk of cancer in observational and intervention studies is summarized in Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4, respectively.

Table 2. Summary of the association between minerals and risk of cancer in observational studies.

| Mineral | Organ | Sample | Association * | Measure | † | Reference | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zinc | Breast | Tissue | Direct | n = 26)Qt | 0.8–11.4 ppm (n = 26) | [70] | [22] | [70] | [22] | ||||||||

| ‡ | Meat, legumes, eggs, fish, grains. | [ | 12 | , | 15 | ,16] | [12] | ||||||||||

| Brain | [ | Tissue | Inverse | 15 | Qt | [76] | ][16] | ||||||||||

| Glioblastoma | Tissue | 0.0403 µg/cm | 2 | (n = 11) | 0.0285 µg/cm | 2 | (n = 11)[23] | [75] | [24] | Selenium | 30–70 | 70 | 300 | 47–145 µg/L | Meat, fish. | [12, | |

| Intake | |||||||||||||||||

| Tissue | † | 0.20 g/kg (n = 6) | [ | Inverse | Qt | 0.27 g/kg (n = 6) | [75] | [24]12 | [76] | [23] | 17] | ][17] | |||||

| Phosphorus | 700,000 | 580,000 | n.d. | 0.8–1.5 × 10 | 3 | µmol/L | Meat, fish. | [12,18] | [12][18] | ||||||||

| Mouth | Intake | None | Qt | ||||||||||||||

| Colon | Serum | 96.4 µg/dL (n = 966) | 97.1 µg/dL (n = 966) | [71] | [25] | [29] | Calcium | 1,000,000 | 750,000 | 2,500,000 | 2500 µmol/L | ||||||

| Milk, fish, legumes. | Serum | Inverse | Qt | [73] | |||||||||||||

| Copper | Glioblastoma | [ | Tissue | 0.0090 µg/cm | 2 | (n = 11)26] | [ | 0.0079 µg/cm | 2 | (n = 11) | 12, | [75] | [24 | 14,19] | [12][14][19] | ||

| Copper | 900 | 1600 | 5000 | 1200 µg/L | Milk, fish, eggs, vegetables. | [ | |||||||||||

| Liver | Serum | 12 | None | HR | [72] | [27] | ,20] | [12][20] | |||||||||

| ] | |||||||||||||||||

| Tissue | † | 0.48 g/kg (n = 6) | 1.26 g/kg (n = 6) | [76] | Iodine | 150 | 95 | 600 | 40–80 µg/L | ||||||||

| [ | 23 | ] | Marine products, eggs, milk, iodized salt. | Serum | Direct | Qt | [78] | [28] | [12,21] | [12][21] | |||||||

| Serum | 27.5 µmol/L ( | n | ‡ | 19.7 µmol/L (n = 52) | ‡ | [ | |||||||||||

| Colon | Tissue | Inverse | OR | [29] | |||||||||||||

| 77 | ] | [ | 30 | ] | |||||||||||||

| Colon | Serum | 138.6 µg/dL (n = 966) | 135.8 µg/dL (n = 966) | [29] | Copper | Liver | |||||||||||

| Pancreas | Serum | SerumDirect | HR | 1432 µg/L (n = 100) | 1098 µg/L (n = 100) | [72] | [27] | ||||||||||

| [ | 74 | ] | [ | 31 | ] | Serum | |||||||||||

| Selenium | Any | Direct | Qt | Serum | 58.8 µg/L * | 84.8 µg/L (n | [78] | [28] | |||||||||

| = 966) | [ | 99 | Mouth | Serum | Direct | Qt | [73] | [26] | |||||||||

| Colon | Tissue | Direct | OR | [29] | |||||||||||||

| Brain | Tissue | Inverse | Qt | [76] | [23] | ||||||||||||

| Serum | Direct | Qt | [77] | [30] | |||||||||||||

| Intake | Inverse | Qt | [75] | [24] | |||||||||||||

| Pancreas | Serum | Direct | Qt | [74] | [31] | ||||||||||||

| Selenium | Esophagus | Tissue | Direct | Qt | [107] | [32] | |||||||||||

| Prostate | Tissue | None | Qt | [103] | [33] | ||||||||||||

| Serum | None | ║ | Qt | [104] | [34] | ||||||||||||

| Any | Serum | None | Qt | [98] | [35] | ||||||||||||

| Serum | Inverse | Qt | [99] | [36] | |||||||||||||

| Liver | Serum | Inverse | Qt | [105] | [37] | ||||||||||||

| Serum | Inverse | Qt | [108] | [38] | |||||||||||||

| Colon | Serum | None | ¶ | IR | [106] | [39] | |||||||||||

| Pancreas | Serum | Inverse | OR | [74] | [31] | ||||||||||||

| Breast | Serum | Inverse | HR | [109] | [40] | ||||||||||||

| Serum | Inverse | HR | [110] | [41] | |||||||||||||

| Lung | Serum | None | Qt | [100] | [42] | ||||||||||||

| Lung | Serum | Direct | HR | [101] | [43] | ||||||||||||

| Kidney | Serum | Inverse | OR | [102] | [44] | ||||||||||||

| Glioblastoma | |||||||||||||||||

| Direct | |||||||||||||||||

| Qt | |||||||||||||||||

| [ | |||||||||||||||||

| 71 | |||||||||||||||||

| ] | |||||||||||||||||

| [ | |||||||||||||||||

| 25 | |||||||||||||||||

| ] | |||||||||||||||||

| , | 106 | ] | [ | 36][39] | |||||||||||||

| Serum | Direct | Qt | [ | 73] | [26] | ||||||||||||

| = 52) | Breast | Serum | None | HR | |||||||||||||

| Esophageal | Tissue | † | 0.73 µg/g (n = 30) | ‡ | 0.59 µg/g (n = 30) | ‡ | [107] | [32] | |||||||||

| Prostate | Tissue | 191 µg/kg (n = 49) | 168 µg/kg (n = 49) | [103] | [33] | ||||||||||||

| Serum | 0.13 µg/g (n = 467) | 0.14 µg/g (n = 936) | [104] | [34] | [ | ||||||||||||

| Breast | Serum | 90.5 ng/mL (n = 100) | 91.3 ng/mL (n = 1186) | [109] | [40 | 166] | [55] | ||||||||||

| ] | Thyroid | Urine | Direct | OR | [168] | [56] | |||||||||||

| [ | 165 | ] | [ | 57 | ] | ||||||||||||

| Zinc | Breast | Tissue | † | 3.5–19.5 ppm ( | |||||||||||||

| Iodine | |||||||||||||||||

| Breast | |||||||||||||||||

| Urine | |||||||||||||||||

| Liver | |||||||||||||||||

| Serum | |||||||||||||||||

| 67.47 µg/L ( | n | = 187) | 108.38 µg/L (n = 120) | [105] | [37] | ||||||||||||

| Colon | Serum | 84.0 µg/L (n = 966) | 85.6 µg/L (n = 966) | [106] | [39] | ||||||||||||

| Pancreas | Serum | 60.0 µg/L (n = 100) | 76.0 µg/L (n = 100) | [74] | [31] | ||||||||||||

| Mouth | |||||||||||||||||

| Intake | |||||||||||||||||

| Direct | |||||||||||||||||

| Direct | |||||||||||||||||

| Qt | |||||||||||||||||

| Rectum | |||||||||||||||||

| Lung | Serum | 166.00 ng/g (n = 48) | 144.74 ng/g (n = 39) | [100] | [42] | ||||||||||||

| Renal | Serum | 161.7 µg/L (n = 401) | 288.8 µg/L (n = 774) | [102] | [44] | Tissue | 1.71 µg/cm | 2 | ( | ||||||||

| Tissue | |||||||||||||||||

| Phosphorus | n | = 11) | 3.01 µg/cm | 2 | (n = 11) | [75] | [24] | ||||||||||

| Iron | Glioblastoma | Tissue | 0.037 µg/cm | 2 | (n = 11) | 0.118 µg/cm | 2 | (n = 11) | [75] | [24] | Qt | [71] | [25] | ||||

| Phosphorus | Brain | Intake | Direct | Qt | [75] | [24] | |||||||||||

| Prostate | Intake | None | |||||||||||||||

| Oral | Serum | 194.6 µg/dL * | 128.6 µg/dL * | [73] | [26] | ||||||||||||

| Calcium | Prostate | Tissue | |||||||||||||||

| Direct | |||||||||||||||||

| Cr | |||||||||||||||||

| [ | |||||||||||||||||

| 167 | |||||||||||||||||

| ] | |||||||||||||||||

| [ | |||||||||||||||||

| 58 | |||||||||||||||||

| ] | |||||||||||||||||

* Direct: high micronutrient concentration is linked to an increased risk of cancer; inverse: low micronutrient concentration is linked to an increased risk of cancer; none: no significance observed. † Cr: correlation; Qt: comparison of levels between groups; HR: hazard ratio; IR: incidence rate ratio; OR: odds ratio; RR: relative risk. ║ Observed inverse trend by ethnic stratification. ¶ Observed inverse trend by sex stratification. # Observed in adenomas but not in carcinomas.

| 657 mg/kg ( | |||||||

| n | |||||||

| = 50) | |||||||

| 1431 mg/kg ( | |||||||

| n | |||||||

| = 49) | |||||||

| [ | |||||||

| 103 | |||||||

| ] | |||||||

| [ | |||||||

| 33 | |||||||

| ] | |||||||

| Oral | |||||||

| Serum | |||||||

| 14.7 mEq/L * | 9.4 mEq/L * | [ | 73 | ] | [26] | ||

| Ovary | Serum | 9.34 mg/dL (n = 170) | 9.31 mg/dL (n = 344) | [180] | [50] | ||

| RR | |||||||

| [ | |||||||

| 133 | |||||||

| ] | |||||||

| [ | |||||||

| 45 | ] | ||||||

| Intake | Direct | Cr | [133] | [45] | |||

| Intake | Direct | OR | [137] | [46] | |||

| Intake | None | OR | [136] | [47] | |||

| Colon | Intake | Inverse | # | RR | [134] | [48] | |

| Bladder | Intake | None | OR | [135] | [49] | ||

| Mouth | Intake | Direct | Qt | [71] | [25] | ||

| Calcium | Prostate | Tissue | Direct | Qt | [103] | [33] | |

| Brain | Intake | Direct | Qt | [75] | [24] | ||

| Ovary | Serum | Direct | Qt | [180] | [50] | ||

| Breast | Serum | Inverse | HR | [181] | [51] | ||

| Mouth | Serum | Direct | Qt | [73] | [26] | ||

| Iron | Any | Serum | Direct/Inverse | HR | [161] | [52] | |

| Intake | Direct | HR | [160] | [53] | |||

| Stomach | Tissue | Direct | Qt | [164] | [54] | ||

| Brain | Intake | Direct | Qt | [75] | [24] | ||

| Mouth | Intake |

* No number of people per group reported. † Comparison between tumoral mass and healthy surrounding tissues. ‡ Estimated from article’s figures using WebPlotDigitizer v. 4.5 [184][59].

Table 4. Summary of the daily intake of minerals in the studies retrieved here.

| Mineral | Cancer Entity | Case Group (Cancer) Mean Mineral Intake Number of Patients |

Control Group (Healthy) Mean Mineral Intake Number of Patients |

Reference | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zinc | Oral | 12,851 µg/day ( | n | = 27) | 11,788 µg/day ( | n | = 86) | [71] | [25] |

| Bladder | 14.5 mg/day ( | n | = 198) | 14.7 mg/day ( | n | = 377) | [135] | [49] | |

| Copper | Bladder | 2.5 mg/day ( | n | = 198) | 2.8 mg/day ( | n | = 377) | [135] | [49] |

| Selenium | Oral | 142.9 µg/day ( | n | = 27) | 166.7 µg/day ( | n | = 86) | [71] | [25] |

| Phosphorus | Oral | 1761 mg/day ( | n | = 27) | 1431 mg/day ( | n | = 86) | [71] | [25] |

| Bladder | 1898.3 mg/day ( | n | = 198) | 1940.4 mg/day ( | n | = 377) | [135] | [49] | |

| Iron | Oral | 22.4 mg/day ( | n | = 27) | 18.9 mg/day ( | n | = 86) | [71] | [25] |

| Bladder | 21.3 mg/day ( | n | = 198) | 23.1 mg/day ( | n | = 377) | [135] | [49] | |

| Calcium | Bladder | 1127.2 mg/day ( | n | = 198) | 1194.5 mg/day ( | n | = 377) | [135] | [49] |

Remarkably, the observation that cancer risk increases with both low and high serum iron levels [161][52] implies that maintaining physiological levels of micronutrients is critical to avoiding an imbalance of cellular biochemistry that can promote oncogenesis. A balanced diet can ensure the intake of the Goldilocks’ quantities of micronutrients, but the depletion of minerals and vitamins in foodstuff makes this increasingly difficult. Regularly checking the mineral levels can help identify whether the physiological range has been met or if the “hidden hunger” has developed increasing the cancer risk.

Given the interdependence of many micronutrients, predicting the role of a single mineral on the oncogenic pathway is cumbersome. For example, serum phosphorus is also linked to calcium and vitamin D and the cellular bioavailability of iron depends on that of vitamin C. Such complexities suggest that minerals may not be suitable cancer biomarkers individually, but a panel of said micronutrients, including vitamins, may provide a more complete picture. Because multiple variables must be considered, it is plausible to expect that micronutrient panels would be best analyzed using machine learning approaches, providing personalized indices to assess potential increased cancer risk.

An imbalanced diet that is often involved in cancer development, is a clear and present danger, especially in industrialized countries. It is not only the high food intake that represents a problem. The vast majority of consumers are unaware of the actual composition of the food or beverages they consume, a situation exacerbated by the fact that food safety authorities do not require manufacturers to declare the actual amounts of micronutrients present in the aliments [185][60]. The trend in micronutrient depletion reported in the last decades, coupled with the increasing prevalence of the “hidden hunger”, suggests that health issues associated with nutritional deficiency will become more prominent in the near future. According to the World Health Organization, two billion individuals worldwide, including those in wealthy countries, suffer from micronutrient deficiency that is largely clinically undetected [186][61]. The addition of micronutrients to food (fortification) has been purposely introduced to fight the spread of nutritional deficiencies [187][62]. However, the effectiveness of this precaution is still debated and does not consider its role on cancer prevention [188,189,190,191][63][64][65][66].

While most knowledge on the medical effect of minerals is associated with high intakes, the impact of mineral deprivation on oncogenesis is still not fully understood. The most recognized medical conditions associated with minerals deficiencies, such as MD, are congenital and include stillbirth, high infant mortality, and impaired development. The role of mineral deficiency in adulthood and its involvement in oncogenesis is still unclear.

The data gathered here highlight a direct association between high intake of micronutrients (namely copper, iron, and iodine) and cancer risk. The message of this review may point to a potential contradiction: while the average amount of micronutrients in food is decreasing, a higher cancer risk is associated with a higher amount of minerals. The solution to this paradox could be two-sided. On the one side, while most mineral concentrations in food are reduced, some minerals are augmented; this is particularly true for phosphorus and iron, particularly from heme. Mineral depletion, on the other side, may cause cells to adopt a transformed phenotype that abnormally increases the intracellular amount of micronutrients, for example, through the aberrant expression of surface importers.

Assuring a well-balanced diet is a difficult task, especially in a food market dominated by advertisements for “junk food”. Rather than relying on labels to report the amounts of selected ingredients (a process hampered by manufacturers’ use of incomprehensible chemical names for key health-associated micronutrients), it is more feasible to embrace population-wide nutritional education. If children are educated on a balanced diet beginning in primary school in a few generations, consumers will be the advisors of their nutritional intake without relying too much on labels. Nutrition deficiency will be reduced in this context, as will the biochemical risks associated with micronutrient overload.

3. Conclusions

In conclusion, herein confirms the potential of micronutrients as biomarkers, although the strong interdependence of micronutrient levels, could necessitate looking at a wide range of micronutrients to increase the significance of the findings. There was a tendency of a direct link between copper, iron, iodine, phosphorus, and zinc levels and the development of different cancer types, with the exception of colon cancer. Selenium serum levels were instead inversely related to cancer risk. However, more data are needed to assess the effectiveness of these biomarkers and if they are suitable only for specific types of cancer. Clustered micronutrient analyses could help the establishment of suitable micronutrient panels with diagnostic value to predict individual cancer risk and to facilitate predictions about the prognosis of particular types of cancer. Furthermore, the individual necessity of supplementation with food supplements, especially micronutrients, should always be critically questioned as long as there is no evident deficiency.

References

- Swinburn, B.; Sacks, G.; Ravussin, E. Increased Food Energy Supply Is More than Sufficient to Explain the US Epidemic of Obesity. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 90, 1453–1456.

- Swinburn, B.A.; Sacks, G.; Hall, K.D.; McPherson, K.; Finegood, D.T.; Moodie, M.L.; Gortmaker, S.L. The Global Obesity Pandemic: Shaped by Global Drivers and Local Environments. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2011, 378, 804–814.

- Thomas, D. A Study on the Mineral Depletion of the Foods Available to Us as a Nation over the Period 1940 to 1991. Nutr. Health 2003, 17, 85–115.

- Thomas, D. The Mineral Depletion of Foods Available to Us as a Nation (1940–2002)—A Review of the 6th Edition of McCance and Widdowson. Nutr. Health 2007, 19, 21–55.

- Mayer, A.-M.B.; Trenchard, L.; Rayns, F. Historical Changes in the Mineral Content of Fruit and Vegetables in the UK from 1940 to 2019: A Concern for Human Nutrition and Agriculture. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 1–12.

- Muthayya, S.; Rah, J.H.; Sugimoto, J.D.; Roos, F.F.; Kraemer, K.; Black, R.E. The Global Hidden Hunger Indices and Maps: An Advocacy Tool for Action. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e67860.

- Biesalski, H.K.; Tinz, J. Multivitamin/Mineral Supplements: Rationale and Safety—A Systematic Review. Nutrition 2017, 33, 76–82.

- Shenkin, A. Micronutrients in Health and Disease. Postgrad. Med. J. 2006, 82, 559–567.

- Calder, P.C. Feeding the Immune System. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2013, 72, 299–309.

- Shakoor, H.; Feehan, J.; Al Dhaheri, A.S.; Ali, H.I.; Platat, C.; Ismail, L.C.; Apostolopoulos, V.; Stojanovska, L. Immune-Boosting Role of Vitamins D, C, E, Zinc, Selenium and Omega-3 Fatty Acids: Could They Help against COVID-19? Maturitas 2021, 143, 1–9.

- Ribatti, D. The Concept of Immune Surveillance against Tumors. The First Theories. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 7175–7180.

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Summary of Tolerable Upper Intake Levels—Version 4. Overview on Tolerable Upper Intake Levels as Derived by the Scientific Committee on Food (SCF) and the EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (NDA). 2018; p. 2. Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/assets/UL_Summary_tables.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2022).

- EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (NDA). Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for Iron. EFSA J. 2014, 13, 4254.

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Summary of Dietary Reference Values—Version 4. Overview on Dietary Reference Values for the EU Population as Derived by the EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (NDA). 2017; p. 5. Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/assets/DRV_Summary_tables_jan_17.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2022).

- EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (NDA). Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for Zinc. EFSA J. 2014, 12, 3844.

- Yokokawa, H.; Fukuda, H.; Saita, M.; Miyagami, T.; Takahashi, Y.; Hisaoka, T.; Naito, T. Serum zinc concentrations and characteristics of zinc deficiency/marginal deficiency among Japanese subjects. J. Gen. Fam. Med. 2020, 21, 248–255.

- EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (NDA). Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for Selenium. EFSA J. 2014, 12, 3846.

- EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (NDA). Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for Phosphorus. EFSA J. 2014, 13, 4185.

- EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (NDA). Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for Calcium. EFSA J. 2015, 13, 4101.

- EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (NDA). Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for Copper. EFSA J. 2015, 13, 4253.

- EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (NDA). Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for Iodine. EFSA J. 2014, 12, 3660.

- Rusch, P.; Hirner, A.V.; Schmitz, O.; Kimmig, R.; Hoffmann, O.; Diel, M. Zinc Distribution within Breast Cancer Tissue of Different Intrinsic Subtypes. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2021, 303, 195–205.

- Dehnhardt, M.; Zoriy, M.V.; Khan, Z.; Reifenberger, G.; Ekström, T.J.; Sabine Becker, J.; Zilles, K.; Bauer, A. Element Distribution Is Altered in a Zone Surrounding Human Glioblastoma Multiforme. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. Organ. Soc. Miner. Trace Elem. GMS 2008, 22, 17–23.

- Wandzilak, A.; Czyzycki, M.; Radwanska, E.; Adamek, D.; Geraki, K.; Lankosz, M. X-ray Fluorescence Study of the Concentration of Selected Trace and Minor Elements in Human Brain Tumours. Spectrochim. Acta Part. B At. Spectrosc. 2015, 114, 52–57.

- Secchi, D.G.; Aballay, L.R.; Galíndez, M.F.; Piccini, D.; Lanfranchi, H.; Brunotto, M. Red Meat, Micronutrients and Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma of Argetine Adult Patients. Nutr. Hosp. 2015, 32, 1214–1221.

- Elango, S.; Samuel, S.; Khashim, Z.; Subbiah, U. Selenium Influences Trace Elements Homeostasis, Cancer Biomarkers in Squamous Cell Carcinoma Patients Administered with Cancerocidal Radiotherapy. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2018, 19, 1785–1792.

- Fang, A.-P.; Chen, P.-Y.; Wang, X.-Y.; Liu, Z.-Y.; Zhang, D.-M.; Luo, Y.; Liao, G.-C.; Long, J.-A.; Zhong, R.-H.; Zhou, Z.-G.; et al. Serum Copper and Zinc Levels at Diagnosis and Hepatocellular Carcinoma Survival in the Guangdong Liver Cancer Cohort. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 144, 2823–2832.

- Tamai, Y.; Iwasa, M.; Eguchi, A.; Shigefuku, R.; Sugimoto, K.; Hasegawa, H.; Takei, Y. Serum Copper, Zinc and Metallothionein Serve as Potential Biomarkers for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237370.

- Stepien, M.; Jenab, M.; Freisling, H.; Becker, N.-P.; Czuban, M.; Tjønneland, A.; Olsen, A.; Overvad, K.; Boutron-Ruault, M.-C.; Mancini, F.R.; et al. Pre-Diagnostic Copper and Zinc Biomarkers and Colorectal Cancer Risk in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition Cohort. Carcinogenesis 2017, 38, 699–707.

- Turecký, L.; Kalina, P.; Uhlíková, E.; Námerová, S.; Krizko, J. Serum Ceruloplasmin and Copper Levels in Patients with Primary Brain Tumors. Klin. Wochenschr. 1984, 62, 187–189.

- Lener, M.R.; Scott, R.J.; Wiechowska-Kozłowska, A.; Serrano-Fernández, P.; Baszuk, P.; Jaworska-Bieniek, K.; Sukiennicki, G.; Marciniak, W.; Muszyńska, M.; Kładny, J.; et al. Serum Concentrations of Selenium and Copper in Patients Diagnosed with Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Res. Treat. 2016, 48, 1056–1064.

- Xie, B.; Lin, J.; Sui, K.; Huang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Hang, W. Differential Diagnosis of Multielements in Cancerous and Non-Cancerous Esophageal Tissues. Talanta 2019, 196, 585–591.

- Çelen, İ.; Müezzinoğlu, T.; Ataman, O.Y.; Bakırdere, S.; Korkmaz, M.; Neşe, N.; Şenol, F.; Lekili, M. Selenium, Nickel, and Calcium Levels in Cancerous and Non-Cancerous Prostate Tissue Samples and Their Relation with Some Parameters. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2015, 22, 13070–13076.

- Gill, J.K.; Franke, A.A.; Steven Morris, J.; Cooney, R.V.; Wilkens, L.R.; Le Marchand, L.; Goodman, M.T.; Henderson, B.E.; Kolonel, L.N. Association of Selenium, Tocopherols, Carotenoids, Retinol, and 15-Isoprostane F(2t) in Serum or Urine with Prostate Cancer Risk: The Multiethnic Cohort. Cancer Causes Control 2009, 20, 1161–1171.

- Coates, R.J.; Weiss, N.S.; Daling, J.R.; Morris, J.S.; Labbe, R.F. Serum Levels of Selenium and Retinol and the Subsequent Risk of Cancer. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1988, 128, 515–523.

- Brodin, O.; Hackler, J.; Misra, S.; Wendt, S.; Sun, Q.; Laaf, E.; Stoppe, C.; Björnstedt, M.; Schomburg, L. Selenoprotein P as Biomarker of Selenium Status in Clinical Trials with Therapeutic Dosages of Selenite. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1067.

- Kim, I.-W.; Bae, S.-M.; Kim, Y.-W.; Liu, H.-B.; Bae, S.H.; Choi, J.Y.; Yoon, S.K.; Chaturvedi, P.K.; Battogtokh, G.; Ahn, W.S. Serum Selenium Levels in Korean Hepatoma Patients. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2012, 148, 25–31.

- Gül-Klein, S.; Haxhiraj, D.; Seelig, J.; Kästner, A.; Hackler, J.; Sun, Q.; Heller, R.A.; Lachmann, N.; Pratschke, J.; Schmelzle, M.; et al. Serum Selenium Status as a Diagnostic Marker for the Prognosis of Liver Transplantation. Nutrients 2021, 13, 619.

- Hughes, D.J.; Fedirko, V.; Jenab, M.; Schomburg, L.; Méplan, C.; Freisling, H.; Bueno-de-Mesquita, H.B.; Hybsier, S.; Becker, N.-P.; Czuban, M.; et al. Selenium Status Is Associated with Colorectal Cancer Risk in the European Prospective Investigation of Cancer and Nutrition Cohort. Int. J. Cancer 2015, 136, 1149–1161.

- Sandsveden, M.; Nilsson, E.; Borgquist, S.; Rosendahl, A.H.; Manjer, J. Prediagnostic Serum Selenium Levels in Relation to Breast Cancer Survival and Tumor Characteristics. Int. J. Cancer 2020, 147, 2424–2436.

- Lubinski, J.; Marciniak, W.; Muszynska, M.; Huzarski, T.; Gronwald, J.; Cybulski, C.; Jakubowska, A.; Debniak, T.; Falco, M.; Kladny, J.; et al. Serum Selenium Levels Predict Survival after Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2018, 167, 591–598.

- Callejón-Leblic, B.; Rodríguez-Moro, G.; Arias-Borrego, A.; Pereira-Vega, A.; Gómez-Ariza, J.L.; García-Barrera, T. Absolute Quantification of Selenoproteins and Selenometabolites in Lung Cancer Human Serum by Column Switching Coupled to Triple Quadrupole Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2020, 1619, 460919.

- Pietrzak, S.; Wójcik, J.; Scott, R.J.; Kashyap, A.; Grodzki, T.; Baszuk, P.; Bielewicz, M.; Marciniak, W.; Wójcik, N.; Dębniak, T.; et al. Influence of the Selenium Level on Overall Survival in Lung Cancer. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. Organ. Soc. Miner. Trace Elem. GMS 2019, 56, 46–51.

- Hsueh, Y.-M.; Lin, Y.-C.; Huang, Y.-L.; Shiue, H.-S.; Pu, Y.-S.; Huang, C.-Y.; Chung, C.-J. Effect of Plasma Selenium, Red Blood Cell Cadmium, Total Urinary Arsenic Levels, and EGFR on Renal Cell Carcinoma. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 750, 141547.

- Zhu, G.; Chen, C.; Hu, B.; Yuan, D.; Chen, W.; Wang, W.; Su, J.; Liu, Z.; Jiao, K.; Chen, X.; et al. Dietary Phosphorus Intake and Serum Prostate-Specific Antigen in Non-Prostate Cancer American Adults: A Secondary Analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 2003–2010. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 29, 322–333.

- Wilson, K.M.; Shui, I.M.; Mucci, L.A.; Giovannucci, E. Calcium and Phosphorus Intake and Prostate Cancer Risk: A 24-y Follow-up Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 101, 173–183.

- Tavani, A.; Bertuccio, P.; Bosetti, C.; Talamini, R.; Negri, E.; Franceschi, S.; Montella, M.; La Vecchia, C. Dietary Intake of Calcium, Vitamin D, Phosphorus and the Risk of Prostate Cancer. Eur. Urol. 2005, 48, 27–33.

- Kesse, E.; Boutron-Ruault, M.-C.; Norat, T.; Riboli, E.; Clavel-Chapelon, F. Dietary Calcium, Phosphorus, Vitamin D, Dairy Products and the Risk of Colorectal Adenoma and Cancer among French Women of the E3N-EPIC Prospective Study. Int. J. Cancer 2005, 117, 137–144.

- Brinkman, M.T.; Buntinx, F.; Kellen, E.; Dagnelie, P.C.; Van Dongen, M.C.J.M.; Muls, E.; Zeegers, M.P. Dietary Intake of Micronutrients and the Risk of Developing Bladder Cancer: Results from the Belgian Case-Control Study on Bladder Cancer Risk. Cancer Causes Control 2011, 22, 469–478.

- Kelly, M.G.; Winkler, S.S.; Lentz, S.S.; Berliner, S.H.; Swain, M.F.; Skinner, H.G.; Schwartz, G.G. Serum Calcium and Serum Albumin Are Biomarkers That Can Discriminate Malignant from Benign Pelvic Masses. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. Publ. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. Cosponsored Am. Soc. Prev. Oncol. 2015, 24, 1593–1598.

- Wulaningsih, W.; Sagoo, H.K.; Hamza, M.; Melvin, J.; Holmberg, L.; Garmo, H.; Malmström, H.; Lambe, M.; Hammar, N.; Walldius, G.; et al. Serum Calcium and the Risk of Breast Cancer: Findings from the Swedish AMORIS Study and a Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1487.

- Wen, C.P.; Lee, J.H.; Tai, Y.-P.; Wen, C.; Wu, S.B.; Tsai, M.K.; Hsieh, D.P.H.; Chiang, H.-C.; Hsiung, C.A.; Hsu, C.Y.; et al. High Serum Iron Is Associated with Increased Cancer Risk. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 6589–6597.

- Zacharski, L.R.; Chow, B.K.; Howes, P.S.; Shamayeva, G.; Baron, J.A.; Dalman, R.L.; Malenka, D.J.; Ozaki, C.K.; Lavori, P.W. Decreased Cancer Risk after Iron Reduction in Patients with Peripheral Arterial Disease: Results from a Randomized Trial. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2008, 100, 996–1002.

- Sawayama, H.; Iwatsuki, M.; Kuroda, D.; Toihata, T.; Uchihara, T.; Koga, Y.; Yagi, T.; Kiyozumi, Y.; Eto, T.; Hiyoshi, Y.; et al. Total Iron-Binding Capacity Is a Novel Prognostic Marker after Curative Gastrectomy for Gastric Cancer. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 23, 671–680.

- Von Holle, A.; O’Brien, K.M.; Sandler, D.P.; Janicek, R.; Weinberg, C.R. Association Between Serum Iron Biomarkers and Breast Cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. Publ. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. Cosponsored Am. Soc. Prev. Oncol. 2021, 30, 422–425.

- Hu, M.-J.; He, J.-L.; Tong, X.-R.; Yang, W.-J.; Zhao, H.-H.; Li, G.-A.; Huang, F. Associations between Essential Microelements Exposure and the Aggressive Clinicopathologic Characteristics of Papillary Thyroid Cancer. Biometals 2021, 34, 909–921.

- Malya, F.U.; Kadioglu, H.; Hasbahceci, M.; Dolay, K.; Guzel, M.; Ersoy, Y.E. The Correlation between Breast Cancer and Urinary Iodine Excretion Levels. J. Int. Med. Res. 2018, 46, 687–692.

- Fan, S.; Li, X.; Zheng, L.; Hu, D.; Ren, X.; Ye, Z. Correlations between the Iodine Concentrations from Dual Energy Computed Tomography and Molecular Markers Ki-67 and HIF-1α in Rectal Cancer: A Preliminary Study. Eur. J. Radiol. 2017, 96, 109–114.

- Rohatgi, A. WebPlotDigitizer: Version 4.5. 2021. Available online: https://automeris.io/WebPlotDigitizer/ (accessed on 21 February 2022).

- Erem, S.; Razzaque, M.S. Dietary Phosphate Toxicity: An Emerging Global Health Concern. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2018, 150, 711–719.

- Tulchinsky, T.H. Micronutrient Deficiency Conditions: Global Health Issues. Public Health Rev. 2010, 32, 243–255.

- Dwyer, J.T.; Woteki, C.; Bailey, R.; Britten, P.; Carriquiry, A.; Gaine, P.C.; Miller, D.; Moshfegh, A.; Murphy, M.M.; Smith Edge, M. Fortification: New Findings and Implications. Nutr. Rev. 2014, 72, 127–141.

- Best, C.; Neufingerl, N.; Del Rosso, J.M.; Transler, C.; van den Briel, T.; Osendarp, S. Can Multi-Micronutrient Food Fortification Improve the Micronutrient Status, Growth, Health, and Cognition of Schoolchildren? A Systematic Review. Nutr. Rev. 2011, 69, 186–204.

- Rowe, L.A. Addressing the Fortification Quality Gap: A Proposed Way Forward. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3899.

- Dewi, N.U.; Mahmudiono, T. Effectiveness of Food Fortification in Improving Nutritional Status of Mothers and Children in Indonesia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2133.

- Das, J.K.; Salam, R.A.; Kumar, R.; Bhutta, Z.A. Micronutrient Fortification of Food and Its Impact on Woman and Child Health: A Systematic Review. Syst. Rev. 2013, 2, 67.

More