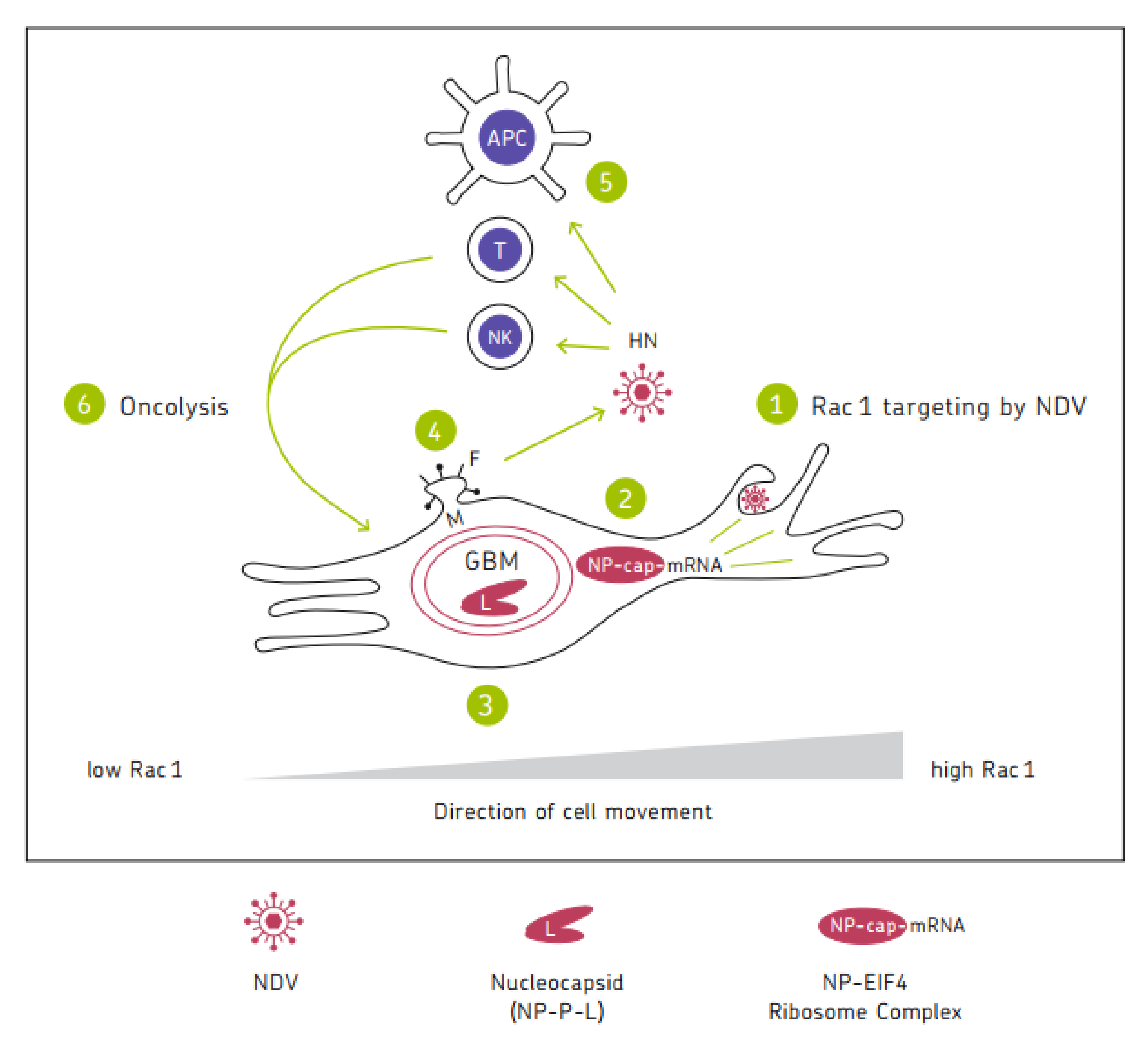

Oncolytic viruses represent interesting anti-cancer agents with high tumor selectivity and immune stimulatory potential. The anti-neoplastic activities of Newcastle Disease Virus (NDV) include (i) the endocytic targeting of the GTPase Rac1 in Ras-transformed human tumorigenic cells; (ii) the switch from cellular protein to viral protein synthesis and the induction of autophagy mediated by viral nucleoprotein NP; (iii) the virus replication mediated by viral RNA polymerase (large protein (L), associated with phosphoprotein (P)); (iv) the facilitation of NDV spread in tumors via the membrane budding of the virus progeny with the help of matrix protein (M) and fusion protein (F); and (v) the oncolysis via apoptosis, necroptosis, pyroptosis, or ferroptosis associated with immunogenic cell death. A special property of this oncolytic virus consists of its potential for breaking therapy resistance in human cancer cells.

- autophagy

- cancer immunotherapy

- cancer vaccine

- cancer therapy resistance

- dendritic cell

- exosome

- immunogenic cell death

- interferon-Ι

- NK cell

- T cell

1. Introduction

2. Basic Information on NDV

2.1. Genome

2.2. Cellular Infection and Viral Replication

Infection of cells by NDV can occur via membrane fusion [3][4] or via endocytosis. In the case of endocytosis, NDV can use various pathways: clathrin-mediated endocytosis in non-lipid raft membrane domains [6], phagocytosis and macropinocytosis in mixed membrane domains [6], and RhoA-dependent endocytosis in lipid raft membrane domains [7]. It can schematically be divided into two steps:- Cellular infection. In the case of membrane fusion, cellular infection starts with the virus binding to a host cell’s surface with α 2,6-linked sialic acid from glycoproteins or glycolipids via the cell-adhesion domain of HN [8]. This is followed by the activation of F. The concerted action of HN and F leads to conformational change, enabling fusion of the viral and the host cell membrane and thereby opening a pore to deliver the viral genome into the cytoplasm [9].

- Replication. When a sufficient amount of NP protein accumulates in the cytoplasm, a switch can occur from RNA transcription to replication. The polymerase complex then ignores the transcription stop signals at the 3′end of each gene and a full-length, positive-sense antigenome is synthesized. These antigenomic replicative intermediates are totally encapsidated by viral NP monomers, just like the full-length, negative-strand genomic RNA/ NP complex.

2.3. NDV Permissive and Non-Permissive Hosts

The permissive hosts of NDV are birds. NDV is widespread in many countries worldwide and can infect over 250 bird species. The non-permissive hosts of NDV are all vertebrates except birds. Class II NDV strains are diverse, with at least 20 genotypes. They include most oncolytic strains of medical interest, e.g., lentogenic Ulster, B1 and La Sota, mesogenic Mukteswar and velogenic Italien, and Hert33.3. Intrinsic Anti-Neoplastic Activities

Anticancer chemotherapeutic drugs with their relatively low level of tumor selectivity exert unwanted non-target side effects. New agents with higher tumor selectivity are therefore urgently needed. As oncolytic NDV has high tumor selectivity in humans, it is important to unravel the molecular mechanisms of this agent.3.1. Targeting Rac1

3.2. Tumor-Selective Virus Replication

3.3. Tumor Selective Viral mRNA Translation

In Ras-transformed tumor cells, the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway (Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK) is activated by the binding of receptor ligands to the cognate receptor tyrosine kinase. With the help of adaptor proteins, the activated receptors convert Ras-GDP to Ras-GTP. The information is further transferred by phosphorylation (activation) of a series of enzymes (Raf, MEK1/2, ERK1/2), which leads to the activation of MAPK-interacting kinase 1 (Mnk1). Activated Mnk1 leads to dissociation of the 4EBP1-eIF4E complex, which results in the release, phosphorylation, and activation of the mRNA cap-binding eucaryotic translation initiation factor eIF4E [16]. The Mnk1/2-eIF4E axis is often dysregulated in cancer and recommended as a potential therapeutic target in melanoma [17].3.4. Tumor-Selective Shift to High Cytoplasmic and Cell Surface Expression of Viral Proteins

The NDV infection of human tumor cells, irradiated by 200 Gray (Gy), was demonstrated by FACS flow cytometry to lead to a shift towards the high-density cell surface expression of viral hemagglutinin-neuraminidase (HN) and F molecules [18]. Such shifts were not observed with nontumorigenic human cells. Pronounced differences between human tumor cell lines and nontumorigenic cells were also observed upon infection by a recombinant lentogenic strain of NDV (Ulster) expressing an incorporated marker transgene (enhanced green-fluorescent protein, EGFP) (NDFL-EGFP). A long-lasting strong cytoplasmic EGFP fluorescence signal was observed in the whole cell population of tumor cells. In nontumorigenic cells, the fluorescence signals were only weak or missing completely [19].3.5. Tumor-Selective Switch from Positive Strand RNA Translation to Negative Strand Antigenome Synthesis

A comparative analysis of human tumorigenic and nontumorigenic cells revealed that within 1 h of infection by NDV, the amount of positive-strand RNA increases in both cell types. In tumor lines, an increase in negative-strand RNA was observed after about 12 h. In contrast, in nontumorigenic cells the expression of negative-strand RNA remained weak and transitory [19].3.6. Tumor-Selective Switch to Autophagy

More detailed information concerning NDV-mediated oncolysis became available within the last 15 years. This includes the unfolded protein ER stress response (UPR), UPR signaling, autophagy, and apoptosis [20]. ER plays an important role in regulating protein synthesis/processing, lipid synthesis, and calcium homeostasis. During virus infection, many viral proteins are synthesized by ER-associated ribosomes and transported into the ER lumen for proper folding or posttranslational modification.3.7. Tumor-Selective Oncolysis: Intrinsic Signaling Pathways

If ER homeostasis cannot be restored, UPR drives the damaged or infected cells to apoptosis [21]. eIF2α-CHOP-BcL-2/JNK and IRE1a-XBP1/JNK signaling was reported to promote apoptosis and inflammation and to support the proliferation of NDV [22]. BcL-2 is a mitochondrial anti-apoptotic protein. Knock down and overexpression studies showed that C/EBP-homologous protein (CHOP), IRE1α, X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1), and jun kinase (JNK) support efficient virus proliferation. The cellular translation shut-off caused by PERK/PKR-eIF2α signaling [19][22] and the hacking of the translational machinery by NDV infection via NP-eIF4E interaction [23] allow NDV-infected tumor cells to translate the viral proteins preferentially.3.8. Oncolysis-Independent Effects

3.9. NDV Spread in Tumors

3.10. Breaking Cancer Therapy Resistancies

So far, it was reported that the anti-neoplastic effects of NDV in humans include (i) targeting the oncogenic protein Rac1, (ii) replicating selectively in tumor cells via autophagy, (iii) selectively destroying tumor cells (viral oncolysis), and (iv) promoting virus spread via syncytia and exosomes. NDV can also suppress the glycolysis pathway, which is an important energy source for cell growth and proliferation [28]. Beyond these anti-neoplastic effects, oncolytic NDV has the intrinsic potential to break the resistance of cancer cells to a variety of therapies [29].4. NDV-Modified Cancer Vaccine for Cancer Immunotherapy

4.1. Successful Application of NDV for Antimetastatic Active-Specific Immunotherapy (ASI)

4.2. Immunogenic Cancer Cell Death and Extrinsic Mechanisms of Oncolysis

The in situ activation of protective T cells can occur not only by post-operative immunization with a virus-modified cancer vaccine [30] but also by the direct inoculation of oncolytic NDV into primary tumors. Zamarin and colleagues demonstrated in 2014 that localized oncolytic virotherapy with NDV overcomes systemic tumor resistance to immune checkpoint blockade immunotherapy [33]. This was interpreted as being based on the induction of immunogenic cell death (ICD) and of systemic protective immunity leading to an abscopal effect at the site of a second untreated tumor.4.3. Induction of Post-Oncolytic Immunity

4.4. Inhibition of Cell Proliferation by IFN-I

4.5. NDV Induced Upregulation of MHC I

4.6. Viral Immune Escape Mechanisms

4.7. NDV-Induced Interferon Response: Inhibition of Virus Replication

4.8. NDV-Induced Interferon Response: Induction of an Anti-Viral State

In mammalian cells, NDV induces a strong type I interferon response [45][29][46][47]. This involves an early and a late phase and leads to the inhibition of virus replication. In short, the early phase is initiated by cytoplasmic viral RNA-activating PKR and the RIG-I/mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein (MAVS) pathway. In the late phase, the released interferons α and ß initiate an amplification loop by activating IFNAR [47][48].5. Immune Cell Activation

When interferon was discovered, its function of virus interference was the first effect seen. Meanwhile, it is well established that type I IFNs exert direct effects not only on viruses but also on the cells of the immune system [49].5.1. Activation of NK Cells, Monocytes, and Macrophages

5.2. Dendritic Cell Activation

Of importance for the induction of adaptive T-cell-mediated immunity is the correct means of DC activation. Human myeloid dendritic cells (mDCs) were infected by NDV to study a cellular response to virus infection that is not inhibited by any viral escape mechanism. A new approach of systems biology integrated genome-wide expression kinetics and time-dependent promoter analysis. Within 18 h, the cells established an anti-viral state. This was explained by a convergent regulatory network of transcription factors [TFs]. A network of 24 TFs was predicted to regulate 779 of the 1351 upregulated genes. The effect of NDV on mDCs was highly reproducible. The timing of this step-wise transcriptional signal propagation appeared as highly conserved [52].5.3. Activation of T Cells

Naïve T cells are maintained in a quiescent state that promotes their survival and persistence [53]. Antigen recognition by naïve CD4+ and CD8+ T cells triggers mTOR activation which programs their differentiation into functionally distinct lineages [54]. Co-stimulatory and co-inhibitory receptors and ligands fine-tune various immune responses [55]. T cell signaling is also modulated by metabolic coordination [53] and by the actin cytoskeleton [56].5.4. Oncolysis-Independent Immune Stimulatory Effects In Vivo

Virus potentiation of tumor vaccine T cell stimulatory capacity was reported to require cell surface binding but not infection [28]. This can explain why therapeutic effects in vivo can be obtained with NDV even against in vitro oncolysis-resistant tumor lines [57][58]. In a human melanoma nude mouse xenotransplant model, strong anti-tumor bystander effects were observed by a 20% co-admixture of melanoma cells pre-infected in vitro by lentogenic NDV (Ulster), suggesting oncolysis-independent innate immunity activation [59].6. Schematic Diagram

Figure 1 shows a chart illustrating the mechanisms of the anti-tumor activity of oncolytic NDV. It represents a cycle of six steps in which the six viral proteins are involved. Mesogenic or velogenic NDV strains with their multicyclic replication capacity have the potential to drive several rounds of the cycle, thereby increasing the intensity and duration of the anti-cancer immune response.

7. Conclusions

References

- Cao, G.-D.; He, X.-B.; Sun, Q.; Chen, S.; Wan, K.; Xu, X.; Feng, X.; Li, P.-P.; Chen, B.; Xiong, M. The Oncolytic Virus in Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 1786.

- Cassel, W.A.; Garrett, R.E. Newcastle disease virus as an antineoplastic agent. Cancer 1965, 18, 863–868.

- Samal, S.K. Newcastle disease and related avian paramyxoviruses. In The Biology of Paramyxoviruses; Samal, S.K., Ed.; Caister Academic Press: Norfolk, UK, 2011; pp. 69–114.

- Song, X.; Shan, H.; Zhu, Y.; Hu, S.; Xue, L.; Chen, Y.; Ding, W.; Niu, T.; Gu, J.; Ouyang, S.; et al. Self-capping of nucleoprotein filaments protects the Newcastle disease virus genome. Elife 2019, 8, e45057.

- Nath, B.; Sharma, K.; Ahire, K.; Goyal, A.; Kumar, S. Structure analysis of the nucleoprotein of Newcastle disease virus: An insight towards its multimeric form in solution. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 151, 402–411.

- Tan, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhan, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Sun, Y.; Qiu, X.; Meng, C.; Song, C.; Liao, Y.; Ding, C. Newcastle disease virus employs macropinocytosis and Rab5a-dependent intracellular trafficking to infect DF-1 cells. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 86117–86133.

- El-Sayed, A.; Harashima, H. Endocytosis of Gene Delivery Vectors: From Clathrin-dependent to Lipid Raft-mediated Endocytosis. Mol. Ther. 2013, 21, 1118–1130.

- Yuan, P.; Paterson, R.G.; Leser, G.P.; Lamb, R.A.; Jardetzky, T.S. Structure of the Ulster Strain Newcastle Disease Virus Hemagglutinin-Neuraminidase Reveals Auto-Inhibitory Interactions Associated with Low Virulence. PLOS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002855.

- Lamb, R.A.; Jardetzky, T.S. Structural basis of viral invasion: Lessons from paramyxovirus F. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2007, 17, 427–436.

- Puhlmann, J.; Puehler, F.; Mumberg, D.; Boukamp, P.; Beier, R. Rac1 is required for oncolytic NDV replication in human cancer cells and establishes a link between tumorigenesis and sensitivity to oncolytic virus. Oncogene 2010, 29, 2205–2215.

- Semenova, G.; Chernoff, J. Targeting PAK1. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2017, 45, 79–88.

- Abdullah, J.M.; Mustafa, Z.; Ideris, A. Newcastle Disease Virus Interaction in Targeted Therapy against Proliferation and Invasion Pathways of Glioblastoma Multiforme. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 386470.

- Mustafa, M.Z.; Shamsuddin, H.S.; Ideris, A.; Ibrahim, R.; Jaafar, R.; Ali, A.M.; Abdullah, J.M. Viability Reduction and Rac1 Gene Downregulation of Heterogeneous Ex-Vivo Glioma Acute Slice Infected by the Oncolytic Newcastle Disease Virus Strain V4UPM. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 248507.

- Reichard, K.W.; Lorence, R.M.; Cascino, C.L.; Peeples, M.E.; Walter, R.J.; Fernando, M.B.; Reyes, H.M.; Greager, J.A. Newcastle disease virus selectively kills human tumor cells. J. Surg. Res. 1992, 52, 448–453.

- Phuangsab, A.; Lorence, R.M.; Reichard, K.W.; Peeples, M.E.; Walter, R.J. Newcastle disease virus therapy of human tumor xenografts: Antitumor effects of local or systemic administration. Cancer Lett. 2001, 172, 27–36.

- Kumar, R.; Khandelwal, N.; Thachamvally, R.; Tripathi, B.N.; Barua, S.; Kashyap, S.K.; Maherchandani, S.; Kumar, N. Role of MAPK/MNK1 signaling in virus replication. Virus Res. 2018, 253, 48–61.

- Zhan, Y.; Yu, S.; Yang, S.; Qiu, X.; Meng, C.; Tan, L.; Song, C.; Liao, Y.; Liu, W.; Sun, Y.; et al. Newcastle Disease virus infection activates PI3K/Akt/mTOR and p38 MAPK/Mnk1 pathways to benefit viral mRNA translation via interaction of the viral NP protein and host eIF4E. PLOS Pathog. 2020, 16, e1008610.

- Washburn, B.; Schirrmacher, V. Human tumor cell infection by Newcastle Disease Virus leads to upregulation of HLA and cell adhesion molecules and to induction of interferons, chemokines and finally apoptosis. Int. J. Oncol. 2002, 21, 85–93.

- Fiola, C.; Peeters, B.; Fournier, P.; Arnold, A.; Bucur, M.; Schirrmacher, V. Tumor selective replication of Newcastle disease virus: Association with defects of tumor cells in antiviral defence. Int. J. Cancer 2006, 119, 328–338.

- Cheng, J.-H.; Sun, Y.-J.; Zhang, F.-Q.; Zhang, X.-R.; Qiu, X.-S.; Yu, L.-P.; Wu, Y.-T.; Ding, C. Newcastle disease virus NP and P proteins induce autophagy via the endoplasmic reticulum stress-related unfolded protein response. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24721.

- Urban-Wojciuk, Z.; Khan, M.M.; Oyler, B.L.; Fåhraeus, R.; Marek-Trzonkowska, N.; Nita-Lazar, A.; Hupp, T.R.; Goodlett, D.R. The Role of TLRs in Anti-cancer Immunity and Tumor Rejection. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2388.

- Li, Y.; Jiang, W.; Niu, Q.; Sun, Y.; Meng, C.; Tan, L.; Song, C.; Qiu, X.; Liao, Y.; Ding, C. eIF2a-CHOP-BcL-2/JNK and IRE1a-XBP1/JNK signaling promote apoptosis and inflammation and support the proliferation of Newcastle disease virus. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 891.

- Prabhu, S.A.; Moussa, O.; Miller, W.H., Jr.; Del Rincón, S.V. The MNK1/2-eIF4E Axis as a Potential Therapeutic Target in Melanoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4055.

- Shtykova, E.V.; Petoukhov, M.V.; Dadinova, L.A.; Fedorova, N.V.; Tashkin, V.Y.; Timofeeva, T.A.; Ksenofontov, A.L.; Loshkarev, N.A.; Baratova, L.A.; Jeffries, C.M.; et al. Solution Structure, Self-Assembly, and Membrane Interactions of the Matrix Protein from Newcastle Disease Virus at Neutral and Acidic pH. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e01450-18.

- Pantua, H.D.; McGinnes, L.W.; Peeples, M.E.; Morrison, T.G. Requirements for the Assembly and Release of Newcastle Disease Virus-Like Particles. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 11062–11073.

- Duan, Z.; Hu, Z.; Zhu, J.; Xu, H.; Chen, J.; Liu, H.; Hu, S.; Liu, X. Mutations in the FPIV motif of Newcastle disease virus matrix protein attenuate virus replication and reduce virus budding. Arch. Virol. 2014, 159, 1813–1819.

- Lamb, R.; Parks, G. In Paramyxoviridae: The viruses and their replication. In Fields Virology, 5th ed.; Knipe, D.M., Howley, P.M., Griffin, D.E., Lamb, R.A., Martin, M.A., Roizman, B., Straus, S.E., Eds.; Lippencott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2007; pp. 1444–1496.

- Al-Ziaydi, A.G.; Al-Shammari, A.M.; Hamzah, M.I.; Kadhim, H.S.; Jabir, M.S. Newcastle disease virus suppress glycolysis pathway and induce breast cancer cells death. Virusdisease 2020, 31, 341–348.

- Schirrmacher, V.; Van Gool, S.; Stuecker, W. Breaking Therapy Resistance: An Update on Oncolytic Newcastle Disease Virus for Improvements of Cancer Therapy. Biomedicines 2019, 7, 66.

- Heicappell, R.; Schirrmacher, V.; von Hoegen, P.; Ahlert, T.; Appelhans, B. Prevention of metastatic spread by postoperative immunotherapy with virally modified autologous tumor cells. I. Parameters for optimal therapeutic effects. Int. J. Cancer 1986, 37, 569–577.

- Zangemeister-Wittke, U.; Kyewski, B.; Schirrmacher, V. Recruitment and activation of tumor-specific immune T cells in situ. CD8+ cells predominate the secondary response in sponge matrices and exert both delayed-type hypersensitivity-like and cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity. J. Immunol. 1989, 143, 379–385.

- Han, J.; Khatwani, N.; Searles, T.G.; Turk, M.J.; Angeles, C.V. Memory CD8+ T cell responses to cancer. Semin. Immunol. 2020, 49, 101435.

- Zamarin, D.; Holmgaard, R.B.; Subudhi, S.K.; Park, J.S.; Mansour, M.; Palese, P.; Merghoub, T.; Wolchok, J.D.; Allison, J.P. Localized Oncolytic Virotherapy Overcomes Systemic Tumor Resistance to Immune Checkpoint Blockade Immunotherapy. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 226ra32.

- Koks, C.A.; Garg, A.D.; Ehrhardt, M.; Riva, M.; Vandenberk, L.; Boon, L.; De Vleeschouwer, S.; Agostinis, P.; Graf, N.; Van Gool, S.W. Newcastle disease virotherapy induces long-term survival and tumor-specific immune memory in orthotopic glioma through the induction of immunogenic cell death. Int. J. Cancer 2015, 136, E313–E325.

- Hong, M.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Q.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Lin, C.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, W.; Li, X.; Zhang, W.; et al. IRF1 inhibits the proliferation and metastasis of colorectal cancer by suppressing the Ras-Rac1 pathway. Cancer Manag. Res. 2018, 11, 369–378.

- Baird, T.D.; Wek, R.C. Eukaryotic Initiation Factor 2 Phosphorylation and Translational Control in Metabolism. Adv. Nutr. 2012, 3, 307–321.

- Ten, R.M.; Blank, V.; Le Bail, O.; Kourilsky, P.; Israël, A. Two factors, IRF1 and KBF1/NF-kappa B, cooperate during induction of MHC class I gene expression by interferon alpha beta or Newcastle disease virus. C. R. Acad. Sci. III 1993, 316, 496–501.

- Schirrmacher, V. Signaling through RIG-I and type I interferon receptor: Immune activation by Newcastle disease virus in man versus immune evasion by Ebola virus (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2015, 36, 3–10.

- Glosson, N.L.; Hudson, A.M. Human herpesvirus-6A and -6B encode viral immunoevasins that downregulate class I MHC molecules. Virology 2007, 365, 125–135.

- Koutsakos, M.; McWilliam, H.E.G.; Aktepe, T.E.; Fritzlar, S.; Illing, P.T.; Mifsud, N.A.; Purcell, A.W.; Rockman, S.; Reading, P.C.; Vivian, J.P.; et al. Downregulation of MHC Class I Expression by Influenza A and B Viruses. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1158.

- Piguet, V. Receptor Modulation in Viral replication: HIV, HSV, HHV-8 and HPV: Same Goal, Different Techniques to Interfere with MHC-I Antigen Presentation. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2005, 285, 199–217.

- Isaacs, A.; Lindenmann, J. Virus interference. I. The interferon. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Boil. Sci. 1957, 147, 258–267.

- Lindemann, J. Viruses as immunological adjuvants in cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1974, 355, 49–75.

- Gresser, I.; Tovey, M.G.; Maury, C.; Bandu, M.T. Role of interferon in the pathogenesis of virus diseases in mice as demonstrated by the use of anti-interferon serum. II. Studies with herpes simplex, Moloney sarcoma, vesicular stomatitis, Newcastle disease, and influenza viruses. J. Exp. Med. 1976, 144, 1316–1323.

- Schirrmacher, V.; Fournier, P. Newcastle Disease Virus: A Promising Vector for Viral Therapy, Immune Therapy, and Gene Therapy of Cancer. In Methods in Molecular Biology, Gene Therapy of Cancer; Walther, W., Stein, U.S., Eds.; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009; Chapter 30; Volume 542, pp. 565–605.

- Wilden, H.; Fournier, P.; Zawatzky, R.; Schirrmacher, V. Expression of RIG-I, IRF3, IFN-beta and IRF7 determines resistance or susceptibility of cells to infection by Newcastle disease virus. Int. J. Oncol. 2009, 34, 971–982.

- Schirrmacher, V.; Fournier, P.; Wilden, H. Importance of retinoic acid-inducible gene I and of receptor for type I interferon for cellular resistance to infection by Newcastle disease virus. Int. J. Oncol. 2012, 40, 287–298.

- Kaufman, H.L.; Kohlhapp, F.J.; Zloza, A. Oncolytic viruses: A new class of immunotherapeutic drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015, 14, 642–662.

- Hervas-Stubbs, S.; Perez-Gracia, J.L.; Rouzaut, A.; Sanmamed, M.F.; Le Bon, A.; Melero, I. Direct Effects of Type I Interferons on Cells of the Immune System. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 17, 2619–2627.

- Mahon, P.J.; Mirza, A.M.; Musich, T.A.; Iorio, R.M. Engineered Intermonomeric Disulfide Bonds in the Globular Domain of Newcastle Disease Virus Hemagglutinin-Neuraminidase Protein: Implications for the Mechanism of Fusion Promotion. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 10386–10396.

- Campbell, K.S.; Cohen, A.D.; Pazina, T. Mechanisms of NK cell activation and clinical activity of the therapeutic SLAM7 antibody, Elotuzumab in multiple myeloma. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2551.

- Zaslavsky, E.; Hershberg, U.; Seto, J.; Pham, A.M.; Marquez, S.; Duke, J.L.; Wetmur, J.G.; Tenoever, B.R.; Sealfon, S.C.; Kleinstein, S.H. Antiviral Response Dictated by Choreographed Cascade of Transcription Factors. J. Immunol. 2010, 184, 2908–2917.

- Chapman, N.M.; Boothby, M.R.; Chi, H. Metabolic coordination of T cell quiescence and activation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20, 55–70.

- Chi, H. Regulation and function of mTOR signalling in T cell fate decisions. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2012, 12, 325–338.

- Azuma, M. Co-signal Molecules in T-Cell Activation: Historical overview and perspective. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019, 1189, 3–23.

- Yu, Y.; Smoligovets, A.A.; Groves, J.T. Modulation of T cell signaling by the actin cytoskeleton. J. Cell Sci. 2013, 126, 1049–1058.

- Oseledchyk, A.; Ricca, J.M.; Gigoux, M.; Ko, B.; Redelman-Sidi, G.; Walther, T.; Liu, C.; Iyer, G.; Merghoub, T.; Wolchok, J.D.; et al. Lysis-independent potentiation of immune checkpoint blockade by oncolytic virus. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 28702–28716.

- Apostolidis, L.; Schirrmacher, V.; Fournier, P. Host mediated anti-tumor effect of oncolytic Newcastle disease virus after locoregional application. Int. J. Oncol. 2007, 31, 1009–1019.

- Schirrmacher, V.; Griesbach, A.; Ahlert, T. Antitumor effects of Newcastle Disease Virus in vivo: Local versus systemic effects. Int. J. Oncol. 2001, 18, 945–952.

- Nguyen, L.K.; Kholodenko, B.N.; Von Kriegsheim, A. Rac1 and RhoA: Networks, loops and bistability. Small GTPases 2018, 9, 316–321.Nguyen, L.K.; Kholodenko, B.N.; Von Kriegsheim, A. Rac1 and RhoA: Networks, loops and bistability. Small GTPases 2018, 9, 316–321.

- De, P.; Aske, J.C.; Dey, N. RAC1 Takes the Lead in Solid Tumors. Cells 2019, 8, 382.De, P.; Aske, J.C.; Dey, N. RAC1 Takes the Lead in Solid Tumors. Cells 2019, 8, 382.

- Liang, Y.; Song, D.Z.; Liang, S.; Zhang, Z.F.; Gao, L.X.; Fan, X.H. The hemagglutinin-neuraminidase protein of Newcastle disease virus upregulates expression of the TRAIL gene in murine natural killer cells through the activation of Syk and NF-kB. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0178746.Liang, Y.; Song, D.Z.; Liang, S.; Zhang, Z.F.; Gao, L.X.; Fan, X.H. The hemagglutinin-neuraminidase protein of Newcastle disease virus upregulates expression of the TRAIL gene in murine natural killer cells through the activation of Syk and NF-kB. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0178746.