Exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) may lead to a rapid decline in health and subsequent death, an unfortunate tyranny of having COPD—an irreversible health condition of 16 million individuals in the USA totaling 60 million in the world. While COPD is the third largest leading cause of death, causing 3.23 million deaths worldwide in 2019 (according to the WHO), most patients with COPD do not receive adequate treatment at the end stages of life. Although death is inevitable, the trajectory towards end-of-life is less predictable in severe COPD. Thus, clinician-patient discussion for end-of-life and palliative care could bring a meaningful life-prospective to patients with advanced COPD. Here, we summarized the current understanding and treatment of COPD.

- chronic bronchitis

- chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- spirometry

- exacerbation

- bronchodilators

- end-of-life care

- palliative care

- global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease

- β2-agonists

- corticosteroids

- dyspnea

- emphysema

1. Introduction

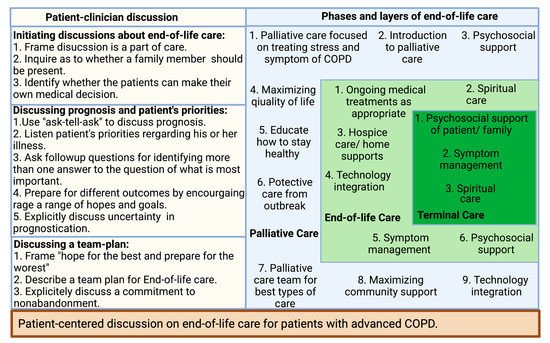

2. Patients Centered Conversation on End-of-Life Care

References

- GOLD 2021. Global Strategy for Prevention, Diagnosis and Management of COPD; In 2021 GOLD Report. 2021, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease—GOLD. Available online: https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/GOLD-REPORT-2021-v1.1-25Nov20_WMV.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Silverman, E.K.; Crapo, J.D.; Make, B.J. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. In Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine; Jameson, J., Fauci, A.S., Kasper, D.L., Hauser, S.L., Longo, D.L., Loscalzo, J., Eds.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2018.

- Barnes, P.J. Sex Differences in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Mechanisms. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care. Med. 2016, 193, 813–814.

- Sin, D.D.; Anthonisen, N.R.; Soriano, J.B.; Agusti, A.G. Mortality in COPD: Role of comorbidities. Eur. Respir. J. 2006, 28, 1245–1257.

- Iglesias, J.R.; Díez-Manglano, J.; García, F.L.; Peromingo, J.A.D.; Almagro, P.; Aguilar, J.M.V. Management of the COPD Patient with Comorbidities: An Experts Recommendation Document. Int. J. Chron. Obs. Pulmon. Dis. 2020, 15, 1015–1037.

- Díez-Manglano, J.; López-García, F. Protocolos: Manejo Diagnóstico y Terapéutico de las Comorbilidades en la EPOC ; Sociedad Española de Medicina Interna (SEMI) y Elsevier SL: Madrid, Spain; Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 1–259.

- Zhou, H.-X.; Ou, X.-M.; Tang, J.-Y.; Wang, L.; Feng, Y.-L. Advanced Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Innovative and Integrated Management Approaches. Chin. Med. J. 2015, 128, 2952–2959.

- Curtis, J.R. Palliative and end-of-life care for patients with severe COPD. Eur. Respir. J. 2008, 32, 796–803.

- Weingaertner, V.; Scheve, C.; Gerdes, V.; Schwarz-Eywill, M.; Prenzel, R.; Bausewein, C.; Higginson, I.J.; Voltz, R.; Herich, L.; Simon, S.T.; et al. Breathlessness, functional status, distress, and palliative care needs over time in patients with advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or lung cancer: A cohort study. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2014, 48, 569–581.e1.

- Janssen, D.J.; Spruit, M.A.; Uszko-Lencer, N.H.; Schols, J.M.; Wouters, E.F. Symptoms, Comorbidities, and Health Care in Advanced Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease or Chronic Heart Failure. J. Palliat. Med. 2011, 14, 735–743.

- Okutan, O.; Tas, T.; Demirer, E.; Kartalogu, Z. Evaluation of quality of life with the chronic obstructive pulmonary disease assessment test in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and the effect of dyspnea on disease-specific quality of life in these patients. Yonsei Med. J. 2013, 54, 1214–1219.

- Tavares, N.; Hunt, K.J.; Jarrett, N.; Wilkinson, T.M. The preferences of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are to discuss palliative care plans with familiar respiratory clinicians, but to delay conversations until their condition deteriorates: A study guided by interpretative phenomenological analysis. Palliat. Med. 2020, 34, 1361–1373.

- Smallwood, N.; Currow, D.; Booth, S.; Spathis, A.; Irving, L.; Philip, J. Attitudes to specialist palliative care and advance care planning in people with COPD: A multi-national survey of palliative and respiratory medicine specialists. BMC Palliat. Care 2018, 17, 115.

- Kuzma, A.M.; Meli, Y.; Meldrum, C.; Jellen, P.; Butler-Lebair, M.; Koczen-Doyle, D.; Rising, P.; Stavrolakes, K.; Brogan., F. Multidisciplinary care of the patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2008, 5, 567–571.

- Team of Specialists. National Jewish Health. Available online: https://www.nationaljewish.org/directory/copd/team (accessed on 2 December 2021).

- Family Members Share in the Care of COPD Patients. Available online: https://www.medicaleconomics.com/view/family-members-share-care-copd-patients. (accessed on 2 December 2021).

- Tonelli, M.R. Pulling the plug on living wills. A critical analysis of advance directives. Chest 1996, 110, 816–822.

- Murray, S.A.; Kendall, M.; Boyd, K.; Sheikh, A. Illness trajectories and palliative care. BMJ 2005, 330, 1007–1011.

- Dales, R.E.; O’Connor, A.; Hebert, P.; Sullivan, K.; Mc Kim, D.; Llewellyn-Thomas, H. Intubation and mechanical ventilation for COPD: Development of an instrument to elicit patient preferences. Chest 1999, 116, 792–800.

- Tilden, V.P.; Tolle, S.W.; Drach, L.L.; Perrin, N.A. Out-of-hospital death: Advance care planning, decedent symptoms, and caregiver burden. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2004, 52, 532–539.

- Norris, K.; Merriman, M.P.; Curtis, J.R.; Asp, C.; Tuholske, L.; Byock, I.R. Next of kin perspectives on the experience of end-of-life care in a community setting. J. Palliat. Med. 2007, 10, 1101–1115.

- Iyer, A.S.; Dionne-Odom, J.N.; Khateeb, D.M.; O’Hare, L.; Tucker, R.O.; Brown, C.J.; Dransfield, M.T.; Bakitas, M.A. A Qualitative Study of Pulmonary and Palliative Care Clinician Perspectives on Early Palliative Care in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. J. Palliat. Med. 2020, 23, 513–526.

- Kendzerska, T.; Nickerson, J.W.; Hsu, A.T.; Gershon, A.S.; Talarico, R.; Mulpuru, S.; Pakhale, S.; Tanuseputro, P. End-of-life care in individuals with respiratory diseases: A population study comparing the dying experience between those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and lung cancer. Int. J. Chron. Obs. Pulmon. Dis. 2019, 14, 1691–1701.

- Fu, P.K.; Yang, M.C.; Wang, C.Y.; Lin, S.P.; Kuo, C.T.; Hsu, C.Y.; Tung, Y.C. Early Do-Not-Resuscitate Directives Decrease Invasive Procedures and Health Care Expenses During the Final Hospitalization of Life of COPD Patients. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2019, 58, 968–976.

- American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine; Center to Advance Palliative Care; Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association, Last Acts Partnership; National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. National consensus project for quality palliative care: Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care, executive summary. J. Palliat. Med. 2004, 7, 611–627.

- Spathis, A.; Booth, S. End of life care in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: In search of a good death. Int. J. Chron. Obs. Pulmon. Dis. 2008, 3, 11–29.

- Curtis, J.R.; Wenrich, M.D.; Carline, J.D.; Shannon, S.E.; Ambrozy, D.M.; Ramsey, P.G. Patients’ perspectives on physician skill in end-of-life care: Differences between patients with COPD, cancer, and AIDS. Chest 2002, 122, 356–362.

- Jones, I.; Kirby, A.; Ormiston, P.; Loomba, Y.; Chan, K.K.; Rout, J.; Nagle, J.; Wardman, L.; Hamilton, S. The needs of patients dying of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the community. Fam. Pr. 2004, 21, 310–313.

- Fried, T.R.; Bradley, E.H.; O’Leary, J. Prognosis communication in serious illness: Perceptions of older patients, caregivers, and clinicians. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2003, 51, 1398–1403.

- Curtis, J.R.; Engelberg, R.; Young, J.P.; Vig, L.K.; Reinke, L.F.; Wenrich, M.D.; McGrath, B.; McCown, E.; Back, A.L. An approach to understanding the interaction of hope and desire for explicit prognostic information among individuals with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or advanced cancer. J. Palliat. Med. 2008, 11, 610–620.

- Paling, J. Strategies to help patients understand risks. BMJ 2003, 327, 745–748.

- Curtis, J.; Engelberg, R.; Nielsen, E.; Au, D.; Patrick, D. Patient-physician communication about end-of-life care for patients with severe COPD. Eur. Respir. J. 2004, 24, 200–205.

- Heffner, J.E.; Fahy, B.; Hilling, L.; Barbieri, C. Outcomes of advance directive education of pulmonary rehabilitation patients. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1997, 155, 1055–1059.

- Heffner, J.E.; Fahy, B.; Hilling, L.; Barbieri, C. Attitudes regarding advance directives among patients in pulmonary rehabilitation. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1996, 154, 1735–1740.

- Scott, M.; Shaver, N.; Lapenskie, J.; Isenberg, S.R.; Saunders, S.; Hsu, A.T.; Tanuseputro, P. Does inpatient palliative care consultation impact outcomes following hospital discharge? A narrative systematic review. Palliat. Med. 2020, 34, 5–15.

- Halpin, D.M.G.; Dionne-Odom, J.N.; Khateeb, D.M.; O’Hare, L.; Tucker, R.O.; Brown, C.J.; Dransfield, M.T.; Bakitas, M.A. Palliative care for people with COPD: Effective but underused. Eur. Respir. J. 2018, 51, 1702645.

- Pinnock, H.; Kendall, M.; Murray, S.A.; Worth, A.; Levack, P.; Porter, M.; MacNee, W.; Sheikh, A. Living and dying with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Multi-perspective longitudinal qualitative study. BMJ 2011, 342, D142.