Frataxin, the protein implicated in Friedreich’s ataxia (FRDA), has a role in the Fe–S cluster biogenesis and possesses a well-defined structure. Several frataxin point mutations, identified in heterozygous FRDA patients, affect the protein structure and function and its binding with partners.

- Fe–S proteins

- Fe–S cluster biogenesis

- genetic diseases

- missense mutations

- protein stability

1. Friedreich’s Ataxia

2. Frataxin and Fe–S Cluster Biogenesis

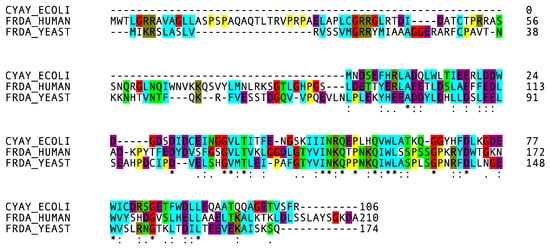

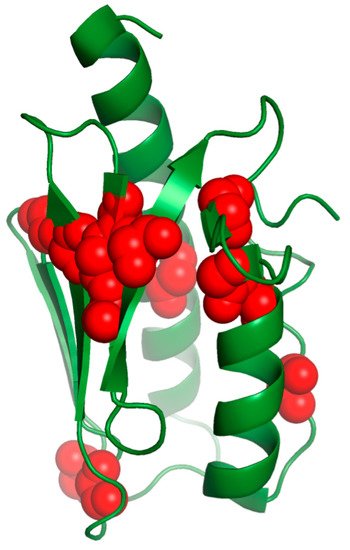

Several diseases are associated with the disruption of cellular iron homeostasis, as both iron overload and deficiency are damaging to cells. The balance of iron in biological systems is thus of fundamental importance. Organisms evolved mechanisms to modulate free iron concentrations in the cell with the formation of prosthetic groups, such as heme and Fe–S clusters. Frataxin is supposed to play a role in the iron–sulfur cluster and heme biosynthesis [6][11]. FRDA patients show an Fe–S cluster deficiency from the beginning of the disorder, suggesting the direct role of frataxin in the Fe–S cluster assembly [46][12]. The Fe–S cluster prosthetic groups are of fundamental importance for protein structure, they play a role in electron transfer, substrate binding and activation, iron and sulfur storage, regulation of gene expression and sometimes in enzyme activity [48,49,50,51][13][14][15][16]. In bacteria, there are three separate pathways for cluster production: the nitrogen fixation machinery (Nif) [52[17][18],53], the Isc machinery for most cellular needs [54,55][19][20] and the Suf machinery, which contributes under stressed conditions [56][21]. The Isc system components have orthologs with high sequence homology in eukaryotes [50,57,58][15][22][23]. The main players are a desulfurase (Nfs1 in eukaryotes, IscS in bacteria) and a scaffold protein (Isu/IscU). The desulfurase is a symmetric dimer containing PLP. This enzyme converts cysteine into alanine, providing sulfur to the scaffold protein on which the cluster is assembled [59][24]. Two chaperones (HscA and HscB in bacteria), with which frataxin has an identical phylogenetic distribution [60][25], are supposed to help the releasing of the Fe–S cluster from the scaffold protein to the acceptor [61][26]. However, HscB has recently been shown to also interact with the desulfurase, opening a new question on its role [62][27]. Electrons necessary for sulfur liberation are provided by a ferredoxin (FdX in bacteria and Yah1 with the ferredoxin reductase Arh1 in eukaryotes) [57][22]. IscA/Isa is able to bind the nascent Fe–S cluster and it is supposed to be an alternative scaffold protein [63][28]. Isd11 is a protein present only in eukaryotes. It plays a role as the adaptor between Nfs1 and the scaffold proteins, to promote sulfur release [66,67]. Another ancillary protein selectively present in prokaryotes is YfhJ [68].Isd11 is a protein present only in eukaryotes. It plays a role as the adaptor between Nfs1 and the scaffold proteins, to promote sulfur release [29][30]. Another ancillary protein selectively present in prokaryotes is YfhJ [31]. Frataxin interacts with the proteins involved in the Fe–S assembly machinery [69,70,71,72][32][33][34][35] through a surface spreading from the acidic ridge to the β4-sheet, as identified by mutating some of the residues belonging to these regions (E108, E111, D124 and W155, N146) [73][36]. Initially, frataxin was supposed to contribute to the Fe–S cluster formation as an iron donor [74,75][37][38]. Independent evidence shows that frataxin could act as a regulator of the reaction speed with an effect that is iron-dependent, by tuning the quantity of clusters formed to match the apo-acceptor concentration [76][39]. Nonetheless, the role of frataxin is still controversial; although in vitro activity assays show that bacterial frataxin, named CyaY, inhibits the cluster formation in bacteria [77[40][41][42],78,79], frataxin activates the reaction in yeast and in the human protein system [80][43]. The interaction between frataxin, the desulfurase and the scaffold protein was revealed and extensively investigated [69,71,78][32][34][41]. In prokaryotes, YfhJ (also called IscX), along with frataxin, was suggested to be a regulator of the IscS activity depending on the iron concentration [81][44]. Intriguingly, in prokaryotes, CyaY competes with YfhJ and FdX for the same site on IscS, and the concentration of iron cations modulate the binding affinity to IscS [78,82,83][41][45][46].3. Frataxin: Structure and Stability

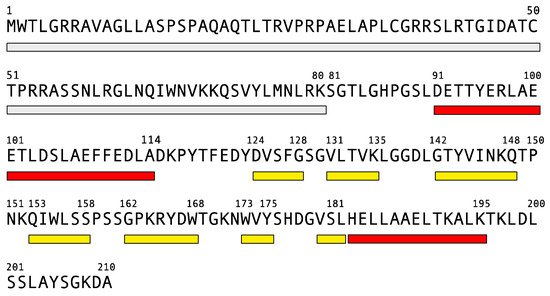

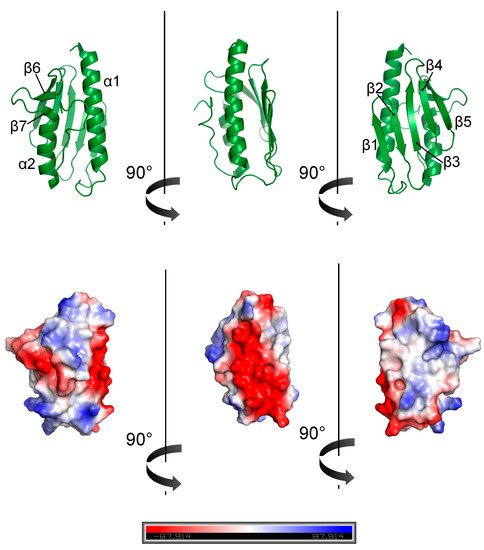

Human frataxin is a nuclear encoded protein of 210 amino acids. The sequence contains a 20-amino acid mitochondrial targeting signal and a spacer (Figure 1) that is removed from the mitochondrial matrix by a two-steps process, to produce mature frataxin [84][47].

4. Frataxin Missense Mutation

The majority of the FRDA patients are compounds homozygous for (GAA)n expansion. Another small but significant number (2–8%) is observed to be heterozygous, with a (GAA)n expansion on one allele and a point mutation on the other [99,100][70][71]. To date, single base pair deletions, insertions and substitutions have been reported, counting at least 44 point mutations reported in the literature [101][72]. FRDA patients homozygous for (GAA)n expansion usually present altered protein levels. The clinical presentation of the heterozygous patients can be either classical or with atypical or milder phenotypes, as missense mutations usually alter the features needed for the biological function or stability depending on the residues. The conserved amino acids of the hydrophobic core are usually essential for the folding; on the contrary, conserved exposed ones are usually involved in its function. In Table 1, we summarize the effects of the mutations on the frataxin structure and function and the disease phenotype in heterozygous patients carrying the most common point mutations identified to date in FRDA patients (Figure 4).

| Mutation | Location | Structural Effects | Other Effects | Tm (°C) | Affected Protein Interaction | Phenotype | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L106S | α1 | Steric strain due to replacement of a apolar residue with a smaller polar one. | milder symptoms | |||||||

| D122Y | loop | Change of a conserved negatively charged residue. | Lower iron binding stoichiometry. | 50.4°C (Correia, 2008) | IscS | mild and atypical disease | ||||

| G130V | turn | β | 1– | β | 2 | Steric strain due to replacement of a glycine that is in a conformation not allowed to other residues. | Higher degradation of frataxin in the cell. Lower iron affinity. | 43.2°C (Correia, 2008) | mild and atypical disease | |

| G137V | turn | β | 1– | β | 2 | Steric strain due to replacement of a glycine that is in a conformation not allowed to other residues and steric hindrance. | Lower efficiency of the folding process. | 46°C (Faggianelli, 2015) | milder symptoms | |

| N146K | β | 3 | Electrostatic strain. | 69.4°C (Castro, 2019) | IscU | classical | ||||

| I154F | β | 4 | Steric strain due to replacement of a hydrophobic residue by a larger one. | Maturation with increase of insoluble intermidiates. | 50.7°C (Correia, 2008) | Isd11 | classical | |||

| W155R | β | 4 | Replacement of a bulky highly conserved aromatic residue with a positively charged one. | 61.4°C (Correia, 2008) | Isd11/Nfs1 and IscU | classical | ||||

| L156P | β | 4 | Disruption in the | β | -sheet by introducing a proline. | IscU | classical | |||

| R165C | β | 5 | Replacement of a conserved positively charged residue with a cysteine that is hydrophobic and might form intermolecular disulfide bond. | IscU | mild and atypical disease | |||||

| W173G | β | 6 | The introduction of a glycine affects the protein folding. | Poorly expressed. | classical | |||||

| L182F | α2 | Steric strain due to replacement of a hydrophobic residue by a larger one. | Prone to degradation. | mild and atypical disease | ||||||

| L182H | α2 | Electrostatic strain due to replacement of a hydrophobic residue with a hydrophilic one. | Prone to degradation. | classical | ||||||

| H183R | α2 | Strain due to replacement of a residue with a bulkier one. | classical | |||||||

| L198R | C-terminal region (CTR) | Electrostatic strain and disruption of the interaction of CTR with α1 and α2. | Lower iron binding affinity. | 54.1°C (Faraj, 2014) | classical |

The mutations of the buried residues (L106, L182, H183 and L186) most likely disrupt the frataxin’s fold and cause FRDA disease.

This is the case for the replacement of a T with a C at position 317 in exon 3, which resulted in L106S missense. The patient carrying this mutation presented milder symptoms, such as the slow rate of disease progression, only lower limb weakness and no cardiac abnormalities or diabetes [103][73]. L106 belongs to the α1 helix and is conserved throughout the species. This is a nonconservative substitution of an apolar amino acid with a smaller polar residue with a lower tendency to form a helix [103][73]. The mutation from T to G was also reported. It causes the change from L106 to a stop codon (L106X) and leads to a truncated form of frataxin [102][74]. Patients carrying this mutation show a total deficiency of frataxin and typical FRDA with a severe course of the disease [32][75].

In other cases, individuals carry a C to T substitution altering the codon at position 182 and present a leucine replaced by the larger phenylalanine (L182F) in the α2 helix. They show atypical and mild symptoms, such as minimal dysarthria, little upper limb disfunction, absent ankle jerks, but reduced knee reflexes and progressively worsening lower limb ataxia [104][76]. Although L182 is supposed to be essential for the frataxin function, as it is a conserved residue, the L182F variant is still able to bind and activate the Fe–S machinery. On the other hand, the L182H mutation shows an alteration in the circular dichroism spectrum, suggesting a change in the secondary structure because of the substitution of a hydrophobic residue with a charged one.

H183 is a buried residue responsible for human frataxin stabilization, as it acts as a lock between the α1 and α2 helices, despite it is a non-conserved residue. Patients with H183R have been reported [100][77]. Although this is a conservative replacement, in which a positively charged amino acid is replaced by another one with similar characteristics, the steric difference between the two residues probably causes a strain disrupting the interaction.

Furthermore, the alteration in frataxin’s structure would arise from the mutation of β-sheet conserved residues with side chains directed towards the hydrophobic core, such as for L156 and W173.

L156 is highly conserved during evolution and a replacement by a proline (L156P) has been reported [100][77]. This is likely to profoundly affect the tridimensional structure, as proline has a high conformational rigidity and acts as a disruptor of the secondary structure. Consequently, the binding with IscU is affected [101][78]. W173 is also highly conserved and its replacement by a smaller residue, such as a glycine (W173G), may deeply affect protein folding [77] [100] to the point that, when trying to produce it, the mutated protein is poorly expressed in the mature form [105][79].

On the other hand, the mutations of conserved exposed residues on the β-sheet plane (I154, N146, W155 and R165) may alter the ability of frataxin to bind its partners and disrupt the function.

Patients with an I154F mutation were found in a restricted area of southern Italy, probably because of the founder effect, in which the mutation is passed down from an individual to other generations. These patients present the typical FRDA phenotype [32,100][10][77]. The missense mutation affects a conserved residue located in β4, a highly conserved region involved in the interaction with Isd11 [105][79]. The maturation of this pathological variant is affected and results in the presence of insoluble intermediates [106][80]. The I154F mutant presents reduced stability with a Tmof 50.7 °C [95][81] and precipitates in the presence of iron [95,107][81][82].

Among the conserved residues on the β-sheet plane, N146, W155 and R165 are significative as they are adjacent in the structure, and the mutation of one has a consequence on the other. Interestingly, the patients carrying the N146K mutation presented classical features of FRDA; despite this, the frataxin mutant showed a stabilized native conformation with a Tm of 69.4 °C [9][83]. It has been suggested that the proximity of W155 and the replacing lysine may imbalance the electrostatic properties of the frataxin surface and affect the binding capacity of frataxin for its protein partners [73][84]. The W155R mutation causes a classical FRDA phenotype as well. W155 belongs to β4 and is an exposed residue responsible for the interaction with ISD11 that is disrupted after the mutation [105][85], as are the interactions with IscU and Nfs1 [73][84]. This mutant retains a native fold and has a slightly reduced stability [6,107][86][82]with a Tm of 61.4 °C [95][81]. The destabilization is expected from the deletion of a π–cation interaction between W155 and contiguous R165, and the electrostatic repulsion resulting from the insertion of arginine. On the contrary, patients with a compound heterozygous for the R165C substitution have a milder disease course (no dysarthria, gait disturbance and ankle jerks) [104][87]. This mutation occurs in a conserved region of β5. It is a nonconservative replacement, altering a basic amino acid to a hydrophobic non-charged one, which might also form an intermolecular disulfide bond and perturb the interaction with IscU [101][78].

As a result of their unique properties of backbone conformations, glycines are often positioned in loops and their substitution necessarily leads to the destabilization of the fold.

The G130V mutation is relatively common in FRDA [104][87]. People presenting frataxin with the G130V mutation have an atypical mild disease with an early onset, spastic gait, absence of dysarthria, retained tendon reflexes, mild or no ataxia and the slow progression of symptoms [100,104,108][77][87][88]. This suggests that, although the residue is highly conserved, the mutation only partially influences the frataxin function. G130V results in a large change in the Tm value (43.2 °C) [95][81] and it seems to affect the maturation of the protein [106][89]. G130 belongs to a turn between strands β1 and β2, and its backbone carbonyl oxygen forms a hydrogen bond with the amide of K147, which is involved in binding the scaffold protein IscU [101][78] and belongs to a ubiquitination site. The mutation of G130 thus results in a higher degradation of frataxin in the cell [109][90] and in the disruption of the interaction with IscU. In addition, the G130V mutation affects the frataxin iron affinity [95,107][81][82].

An FRDA patient with a compound heterozygous with an G137V substitution was also reported. It described an onset at 25 years of age and phenotypes, such as gait and trunk ataxia, mild dysarthria, absent tendon reflexes in the upper and lower limbs and impaired position and vibratory sense in the lower limbs [110][91]. Frataxin carrying the G137V mutation presented no effects on the structure or activity of the protein, but had a reduced conformational stability with a melting temperature of 46 °C. This is supposed to affect the efficiency of the folding process causing reduced levels of the active protein [110][91]. G137 is not an evolutionary conserved residue and is located in the C-terminal globular domain at the end of the β2 strand. Its mutation to a valine is supposed to have an important influence on the turn and, additionally, to cause steric hindrance with other residues. Interestingly, D122 packs against G137, suggesting that the two mutations have the same effect [110][91]. Similar to the patients carrying the G137V mutation, those found with the D122Y mutation had a mild and atypical disease [100][77]. D122 belongs to the N-terminus and its mutation does not affect the folding. However, by changing the polarity of the anionic surface, it reduces the protein stability [6] with a Tm of 50.4 °C [95][81]. The D122Y variant has a lower iron binding stoichiometry [95][81] and a perturbed interaction with the desulfurase [101][78].

As it was already described above, the C-terminal tail plays a crucial role in the stabilization of the fold [16,94][92][93]. A compound heterozygous patient was reported to present a base substitution that converted leucine to arginine at amino acid position 198 (L198R), located in an apolar environment in the C-terminus. The patient showed a typical FRDA phenotype [111][94]. L198 is a conserved residue and the mutation causes an alteration in charge with a consequent destabilization of the protein, with a Tm of 54.1 °C [112] [95], due to the disruption of the interaction of the C-terminus with the α1 and α2 helices. L198R also showed a lower iron binding capability [112][95]. To determine the relevance of the frataxin C-terminus, other mutations at this position were also investigated (L198A and L198C). They all presented protein destabilization [113][96] as well as the absence of the C-terminus (residues 196–210) [94,112][93][95]. On the other hand, the truncation of frataxin at residue 193 determines FRDA with a rapid disease progression [114][97].

Such a variety of examples prove that similar dramatic or milder phenotypes do not necessarily derive from the same cause and, actually, may have a different origin at a molecular level. Depending on their localization in the structure, specific mutations can impair the function by disrupting the interaction with essential partners and decrease the protein stability leading to the degradation or disruption of the folding.

References

- Campuzano, V.; Montermini, L.; Molto, M.D.; Pianese, L.; Cossee, M.; Cavalcanti, F.; Monros, E.; Rodius, F.; Duclos, F.; Monticelli, A.; et al. Friedreich’s ataxia: Autosomal recessive disease caused by an intronic GAA triplet repeat expansion. Science 1996, 271, 1423–1427.

- Harding, A.E. Friedreich’s ataxia: A clinical and genetic study of 90 families with an analysis of early diagnostic criteria and intrafamilial clustering of clinical features. Brain 1981, 104, 589–620.

- Geoffroy, G.; Barbeau, A.; Breton, G.; Lemieux, B.; Aube, M.; Leger, C.; Bouchard, J.P. Clinical Description and Roentgenologic Evaluation of Patients with Friedreich’s Ataxia. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. J. Can. Des Sci. Neurol. 1976, 3, 279–286.

- Durr, A.; Cossee, M.; Agid, Y.; Campuzano, V.; Mignard, C.; Penet, C.; Mandel, J.L.; Brice, A.; Koenig, M. Clinical and genetic abnormalities in patients with Friedreich’s ataxia. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996, 335, 1169–1175.

- Finocchiaro, G.; Baio, G.; Micossi, P.; Pozza, G.; di Donato, S. Glucose metabolism alterations in Friedreich’s ataxia. Neurology 1988, 38, 1292–1296.

- Chamberlain, S.; Shaw, J.; Wallis, J.; Rowland, A.; Chow, L.; Farrall, M.; Keats, B.; Richter, A.; Roy, M.; Melancon, S.; et al. Genetic homogeneity at the Friedreich ataxia locus on chromosome 9. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1989, 44, 518–521.

- Priller, J.; Scherzer, C.R.; Faber, P.W.; MacDonald, M.E.; Young, A.B. Frataxin gene of Friedreich’s ataxia is targeted to mitochondria. Ann. Neurol. 1997, 42, 265–269.

- Koutnikova, H.; Campuzano, V.; Foury, F.; Dolle, P.; Cazzalini, O.; Koenig, M. Studies of human, mouse and yeast homologues indicate a mitochondrial function for frataxin. Nat. Genet. 1997, 16, 345–351.

- Campuzano, V.; Montermini, L.; Lutz, Y.; Cova, L.; Hindelang, C.; Jiralerspong, S.; Trottier, Y.; Kish, S.J.; Faucheux, B.; Trouillas, P.; et al. Frataxin is reduced in Friedreich ataxia patients and is associated with mitochondrial membranes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1997, 6, 1771–1780.

- Campuzano, V.; Montermini, L.; Molto, M.D.; Pianese, L.; Cossee, M.; Cavalcanti, F.; Monros, E.; Rodius, F.; Duclos, F.; Monticelli, A.; et al. Friedreich’s ataxia: Autosomal recessive disease caused by an intronic GAA triplet repeat expansion. Science 1996, 271, 1423–1427.

- Pastore, A.; Puccio, H. Frataxin: A protein in search for a function. J. Neurochem. 2013, 126 (Suppl. S1), 43–52.

- Rotig, A.; de Lonlay, P.; Chretien, D.; Foury, F.; Koenig, M.; Sidi, D.; Munnich, A.; Rustin, P. Aconitase and mitochondrial iron-sulphur protein deficiency in Friedreich ataxia. Nat. Genet. 1997, 17, 215–217.

- Fuss, J.O.; Tsai, C.L.; Ishida, J.P.; Tainer, J.A. Emerging critical roles of Fe-S clusters in DNA replication and repair. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1853, 1253–1271.

- Chen, O.S.; Crisp, R.J.; Valachovic, M.; Bard, M.; Winge, D.R.; Kaplan, J. Transcription of the yeast iron regulon does not respond directly to iron but rather to iron-sulfur cluster biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 29513–29518.

- Johnson, D.C.; Dean, D.R.; Smith, A.D.; Johnson, M.K. Structure, function, and formation of biological iron-sulfur clusters. Annu Rev. Biochem. 2005, 74, 247–281.

- Beinert, H.; Holm, R.H.; Munck, E. Iron-sulfur clusters: Nature’s modular, multipurpose structures. Science 1997, 277, 653–659.

- Frazzon, J.; Fick, J.R.; Dean, D.R. Biosynthesis of iron-sulphur clusters is a complex and highly conserved process. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2002, 30, 680–685.

- Rees, D.C.; Howard, J.B. Nitrogenase: Standing at the crossroads. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2000, 4, 559–566.

- Kispal, G.; Csere, P.; Prohl, C.; Lill, R. The mitochondrial proteins Atm1p and Nfs1p are essential for biogenesis of cytosolic Fe/S proteins. EMBO J. 1999, 18, 3981–3989.

- Zheng, L.; Cash, V.L.; Flint, D.H.; Dean, D.R. Assembly of iron-sulfur clusters. Identification of an iscSUA-hscBA-fdx gene cluster from Azotobacter vinelandii. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 13264–13272.

- Takahashi, Y.; Tokumoto, U. A third bacterial system for the assembly of iron-sulfur clusters with homologs in archaea and plastids. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 28380–28383.

- Lill, R.; Muhlenhoff, U. Iron-sulfur-protein biogenesis in eukaryotes. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2005, 30, 133–141.

- Mansy, S.S.; Cowan, J.A. Iron-sulfur cluster biosynthesis: Toward an understanding of cellular machinery and molecular mechanism. Acc. Chem. Res. 2004, 37, 719–725.

- Urbina, H.D.; Silberg, J.J.; Hoff, K.G.; Vickery, L.E. Transfer of sulfur from IscS to IscU during Fe/S cluster assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 44521–44526.

- Huynen, M.A.; Snel, B.; Bork, P.; Gibson, T.J. The phylogenetic distribution of frataxin indicates a role in iron-sulfur cluster protein assembly. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001, 10, 2463–2468.

- Puglisi, R.; Pastore, A. The role of chaperones in iron-sulfur cluster biogenesis. FEBS Lett. 2018, 592, 4011–4019.

- Puglisi, R.; Yan, R.; Adinolfi, S.; Pastore, A. A New Tessera into the Interactome of the isc Operon: A Novel Interaction between HscB and IscS. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2016, 3, 48.

- Krebs, C.; Agar, J.N.; Smith, A.D.; Frazzon, J.; Dean, D.R.; Huynh, B.H.; Johnson, M.K. IscA, an alternate scaffold for Fe-S cluster biosynthesis. Biochemistry 2001, 40, 14069–14080.

- Adam, A.C.; Bornhovd, C.; Prokisch, H.; Neupert, W.; Hell, K. The Nfs1 interacting protein Isd11 has an essential role in Fe/S cluster biogenesis in mitochondria. EMBO J. 2006, 25, 174–183.

- Wiedemann, N.; Urzica, E.; Guiard, B.; Muller, H.; Lohaus, C.; Meyer, H.E.; Ryan, M.T.; Meisinger, C.; Muhlenhoff, U.; Lill, R.; et al. Essential role of Isd11 in mitochondrial iron-sulfur cluster synthesis on Isu scaffold proteins. EMBO J. 2006, 25, 184–195.

- Pastore, C.; Adinolfi, S.; Huynen, M.A.; Rybin, V.; Martin, S.; Mayer, M.; Bukau, B.; Pastore, A. YfhJ, a molecular adaptor in iron-sulfur cluster formation or a frataxin-like protein? Structure 2006, 14, 857–867.

- Gerber, J.; Muhlenhoff, U.; Lill, R. An interaction between frataxin and Isu1/Nfs1 that is crucial for Fe/S cluster synthesis on Isu1. EMBO Rep. 2003, 4, 906–911.

- Muhlenhoff, U.; Gerber, J.; Richhardt, N.; Lill, R. Components involved in assembly and dislocation of iron-sulfur clusters on the scaffold protein Isu1p. EMBO J. 2003, 22, 4815–4825.

- Ramazzotti, A.; Vanmansart, V.; Foury, F. Mitochondrial functional interactions between frataxin and Isu1p, the iron-sulfur cluster scaffold protein, in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 2004, 557, 215–220.

- Puglisi, R.; Boeri Erba, E.; Pastore, A. A Guide to Native Mass Spectrometry to determine complex interactomes of molecular machines. FEBS J. 2020, 287, 2428–2439.

- Schmucker, S.; Martelli, A.; Colin, F.; Page, A.; Wattenhofer-Donze, M.; Reutenauer, L.; Puccio, H. Mammalian frataxin: An essential function for cellular viability through an interaction with a preformed ISCU/NFS1/ISD11 iron-sulfur assembly complex. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e16199.

- Yoon, T.; Cowan, J.A. Iron-sulfur cluster biosynthesis. Characterization of frataxin as an iron donor for assembly of clusters in ISU-type proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 6078–6084.

- Layer, G.; Ollagnier-de Choudens, S.; Sanakis, Y.; Fontecave, M. Iron-sulfur cluster biosynthesis: Characterization of Escherichia coli CYaY as an iron donor for the assembly of clusters in the scaffold IscU. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 16256–16263.

- Adinolfi, S.; Iannuzzi, C.; Prischi, F.; Pastore, C.; Iametti, S.; Martin, S.R.; Bonomi, F.; Pastore, A. Bacterial frataxin CyaY is the gatekeeper of iron-sulfur cluster formation catalyzed by IscS. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009, 16, 390–396.

- Foury, F.; Pastore, A.; Trincal, M. Acidic residues of yeast frataxin have an essential role in Fe-S cluster assembly. EMBO Rep. 2007, 8, 194–199.

- Prischi, F.; Konarev, P.V.; Iannuzzi, C.; Pastore, C.; Adinolfi, S.; Martin, S.R.; Svergun, D.I.; Pastore, A. Structural bases for the interaction of frataxin with the central components of iron-sulphur cluster assembly. Nat. Commun. 2010, 1, 95.

- Marengo, M.; Puglisi, R.; Oliaro-Bosso, S.; Pastore, A.; Adinolfi, S. Enzymatic and Chemical In Vitro Reconstitution of Iron-Sulfur Cluster Proteins. Methods Mol. Biol. 2021, 2353, 79–95.

- Tsai, C.L.; Barondeau, D.P. Human frataxin is an allosteric switch that activates the Fe-S cluster biosynthetic complex. Biochemistry 2010, 49, 9132–9139.

- Adinolfi, S.; Puglisi, R.; Crack, J.C.; Iannuzzi, C.; Dal Piaz, F.; Konarev, P.V.; Svergun, D.I.; Martin, S.; Le Brun, N.E.; Pastore, A. The Molecular Bases of the Dual Regulation of Bacterial Iron Sulfur Cluster Biogenesis by CyaY and IscX. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2017, 4, 97.

- Kim, J.H.; Bothe, J.R.; Frederick, R.O.; Holder, J.C.; Markley, J.L. Role of IscX in iron-sulfur cluster biogenesis in Escherichia coli. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 7933–7942.

- Yan, R.; Konarev, P.V.; Iannuzzi, C.; Adinolfi, S.; Roche, B.; Kelly, G.; Simon, L.; Martin, S.R.; Py, B.; Barras, F.; et al. Ferredoxin competes with bacterial frataxin in binding to the desulfurase IscS. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 24777–24787.

- Gordon, D.M.; Kogan, M.; Knight, S.A.; Dancis, A.; Pain, D. Distinct roles for two N-terminal cleaved domains in mitochondrial import of the yeast frataxin homolog, Yfh1p. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001, 10, 259–269.

- Cho, S.J.; Lee, M.G.; Yang, J.K.; Lee, J.Y.; Song, H.K.; Suh, S.W. Crystal structure of Escherichia coli CyaY protein reveals a previously unidentified fold for the evolutionarily conserved frataxin family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 8932–8937.

- Dhe-Paganon, S.; Shigeta, R.; Chi, Y.I.; Ristow, M.; Shoelson, S.E. Crystal structure of human frataxin. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 30753–30756.

- He, Y.; Alam, S.L.; Proteasa, S.V.; Zhang, Y.; Lesuisse, E.; Dancis, A.; Stemmler, T.L. Yeast frataxin solution structure, iron binding, and ferrochelatase interaction. Biochemistry 2004, 43, 16254–16262.

- Lee, M.G.; Cho, S.J.; Yang, J.K.; Song, H.K.; Suh, S.W. Crystallization and preliminary X-ray crystallographic analysis of Escherichia coli CyaY, a structural homologue of human frataxin. Acta Cryst. D Biol. Cryst. 2000, 56, 920–921.

- Musco, G.; Stier, G.; Kolmerer, B.; Adinolfi, S.; Martin, S.; Frenkiel, T.; Gibson, T.; Pastore, A. Towards a structural understanding of Friedreich’s ataxia: The solution structure of frataxin. Structure 2000, 8, 695–707.

- Nair, M.; Adinolfi, S.; Pastore, C.; Kelly, G.; Temussi, P.; Pastore, A. Solution structure of the bacterial frataxin ortholog, CyaY: Mapping the iron binding sites. Structure 2004, 12, 2037–2048.

- Roman, E.A.; Faraj, S.E.; Cousido-Siah, A.; Mitschler, A.; Podjarny, A.; Santos, J. Frataxin from Psychromonas ingrahamii as a model to study stability modulation within the CyaY protein family. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1834, 1168–1180.

- Rasheed, M.; Jamshidiha, M.; Puglisi, R.; Yan, R.; Cota, E.; Pastore, A. Structural and functional characterization of a frataxin from a thermophilic organism. FEBS J. 2019, 286, 495–506.

- Popovic, M.; Sanfelice, D.; Pastore, C.; Prischi, F.; Temussi, P.A.; Pastore, A. Selective observation of the disordered import signal of a globular protein by in-cell NMR: The example of frataxins. Protein Sci. 2015, 24, 996–1003.

- Bencze, K.Z.; Kondapalli, K.C.; Cook, J.D.; McMahon, S.; Millan-Pacheco, C.; Pastor, N.; Stemmler, T.L. The structure and function of frataxin. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2006, 41, 269–291.

- Adinolfi, S.; Nair, M.; Politou, A.; Bayer, E.; Martin, S.; Temussi, P.; Pastore, A. The factors governing the thermal stability of frataxin orthologues: How to increase a protein’s stability. Biochemistry 2004, 43, 6511–6518.

- Correia, A.R.; Pastore, C.; Adinolfi, S.; Pastore, A.; Gomes, C.M. Dynamics, stability and iron-binding activity of frataxin clinical mutants. FEBS J. 2008, 275, 3680–3690.

- Pandolfo, M.; Pastore, A. The pathogenesis of Friedreich ataxia and the structure and function of frataxin. J. Neurol. 2009, 256 (Suppl. S1), 9–17.

- Castro, I.H.; Pignataro, M.F.; Sewell, K.E.; Espeche, L.D.; Herrera, M.G.; Noguera, M.E.; Dain, L.; Nadra, A.D.; Aran, M.; Smal, C.; et al. Frataxin Structure and Function. In Macromolecular Protein Complexes II: Structure and Function; Harris, J.R., Marles-Wright, J., Eds.; Springer, Cham: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 93, pp. 393–438.

- Alfano, C.; Sanfelice, D.; Martin, S.R.; Pastore, A.; Temussi, P.A. An optimized strategy to measure protein stability highlights differences between cold and hot unfolded states. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15428.

- Puglisi, R.; Brylski, O.; Alfano, C.; Martin, S.R.; Pastore, A.; Temussi, P.A. Quantifying the thermodynamics of protein unfolding using 2D NMR spectroscopy. Commun. Chem. 2020, 3, 100.

- Pastore, A.; Martin, S.R.; Politou, A.; Kondapalli, K.C.; Stemmler, T.; Temussi, P.A. Unbiased cold denaturation: Low- and high-temperature unfolding of yeast frataxin under physiological conditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 5374–5375.

- Puglisi, R.; Karunanithy, G.; Hansen, D.F.; Pastore, A.; Temussi, P.A. The anatomy of unfolding of Yfh1 is revealed by site-specific fold stability analysis measured by 2D NMR spectroscopy. Commun. Chem. 2021, 4, 127.

- Sanfelice, D.; Politou, A.; Martin, S.R.; De Los Rios, P.; Temussi, P.; Pastore, A. The effect of crowding and confinement: A comparison of Yfh1 stability in different environments. Phys. Biol. 2013, 10, 045002.

- Adrover, M.; Martorell, G.; Martin, S.R.; Urosev, D.; Konarev, P.V.; Svergun, D.I.; Daura, X.; Temussi, P.; Pastore, A. The role of hydration in protein stability: Comparison of the cold and heat unfolded states of Yfh1. J. Mol. Biol. 2012, 417, 413–424.

- Sanfelice, D.; Temussi, P.A. Cold denaturation as a tool to measure protein stability. Biophys. Chem. 2016, 208, 4–8.

- Sanfelice, D.; Puglisi, R.; Martin, S.R.; Di Bari, L.; Pastore, A.; Temussi, P.A. Yeast frataxin is stabilized by low salt concentrations: Cold denaturation disentangles ionic strength effects from specific interactions. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e95801.

- Gellera, C.; Castellotti, B.; Mariotti, C.; Mineri, R.; Seveso, V.; Didonato, S.; Taroni, F. Frataxin gene point mutations in Italian Friedreich ataxia patients. Neurogenetics 2007, 8, 289–299.

- Cossee, M.; Durr, A.; Schmitt, M.; Dahl, N.; Trouillas, P.; Allinson, P.; Kostrzewa, M.; Nivelon-Chevallier, A.; Gustavson, K.H.; Kohlschutter, A.; et al. Friedreich’s ataxia: Point mutations and clinical presentation of compound heterozygotes. Ann. Neurol. 1999, 45, 200–206.

- Galea, C.A.; Huq, A.; Lockhart, P.J.; Tai, G.; Corben, L.A.; Yiu, E.M.; Gurrin, L.C.; Lynch, D.R.; Gelbard, S.; Durr, A.; et al. Compound heterozygous FXN mutations and clinical outcome in friedreich ataxia. Ann. Neurol. 2016, 79, 485–495.

- Bartolo, C.; Mendell, J.R.; Prior, T.W. Identification of a missense mutation in a Friedreich’s ataxia patient: Implications for diagnosis and carrier studies. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1998, 79, 396–399.

- Pook, M.A.; Al-Mahdawi, S.A.; Thomas, N.H.; Appleton, R.; Norman, A.; Mountford, R.; Chamberlain, S. Identification of three novel frameshift mutations in patients with Friedreich’s ataxia. J. Med. Genet. 2000, 37, E38.

- Campuzano, V.; Montermini, L.; Molto, M.D.; Pianese, L.; Cossee, M.; Cavalcanti, F.; Monros, E.; Rodius, F.; Duclos, F.; Monticelli, A.; et al. Friedreich’s ataxia: Autosomal recessive disease caused by an intronic GAA triplet repeat expansion. Science 1996, 271, 1423–1427.

- Forrest, S.M.; Knight, M.; Delatycki, M.B.; Paris, D.; Williamson, R.; King, J.; Yeung, L.; Nassif, N.; Nicholson, G.A. The correlation of clinical phenotype in Friedreich ataxia with the site of point mutations in the FRDA gene. Neurogenetics 1998, 1, 253–257.

- Cossee, M.; Durr, A.; Schmitt, M.; Dahl, N.; Trouillas, P.; Allinson, P.; Kostrzewa, M.; Nivelon-Chevallier, A.; Gustavson, K.H.; Kohlschutter, A.; et al. Friedreich’s ataxia: Point mutations and clinical presentation of compound heterozygotes. Ann. Neurol. 1999, 45, 200–206.

- Galea, C.A.; Huq, A.; Lockhart, P.J.; Tai, G.; Corben, L.A.; Yiu, E.M.; Gurrin, L.C.; Lynch, D.R.; Gelbard, S.; Durr, A.; et al. Compound heterozygous FXN mutations and clinical outcome in friedreich ataxia. Ann. Neurol. 2016, 79, 485–495.

- Shan, Y.; Napoli, E.; Cortopassi, G. Mitochondrial frataxin interacts with ISD11 of the NFS1/ISCU complex and multiple mitochondrial chaperones. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2007, 16, 929–941.

- Sanfelice, D.; Politou, A.; Martin, S.R.; De Los Rios, P.; Temussi, P.; Pastore, A. The effect of crowding and confinement: A comparison of Yfh1 stability in different environments. Phys. Biol. 2013, 10, 045002.

- Correia, A.R.; Pastore, C.; Adinolfi, S.; Pastore, A.; Gomes, C.M. Dynamics, stability and iron-binding activity of frataxin clinical mutants. FEBS J. 2008, 275, 3680–3690.

- Correia, A.R.; Adinolfi, S.; Pastore, A.; Gomes, C.M. Conformational stability of human frataxin and effect of Friedreich’s ataxia-related mutations on protein folding. Biochem. J. 2006, 398, 605–611.

- Castro, I.H.; Pignataro, M.F.; Sewell, K.E.; Espeche, L.D.; Herrera, M.G.; Noguera, M.E.; Dain, L.; Nadra, A.D.; Aran, M.; Smal, C.; et al. Frataxin Structure and Function. In Macromolecular Protein Complexes II: Structure and Function; Harris, J.R., Marles-Wright, J., Eds.; Springer, Cham: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 93, pp. 393–438.

- Schmucker, S.; Martelli, A.; Colin, F.; Page, A.; Wattenhofer-Donze, M.; Reutenauer, L.; Puccio, H. Mammalian frataxin: An essential function for cellular viability through an interaction with a preformed ISCU/NFS1/ISD11 iron-sulfur assembly complex. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e16199.

- Shan, Y.; Napoli, E.; Cortopassi, G. Mitochondrial frataxin interacts with ISD11 of the NFS1/ISCU complex and multiple mitochondrial chaperones. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2007, 16, 929–941.

- Pastore, A.; Puccio, H. Frataxin: A protein in search for a function. J. Neurochem. 2013, 126 (Suppl. S1), 43–52.

- Forrest, S.M.; Knight, M.; Delatycki, M.B.; Paris, D.; Williamson, R.; King, J.; Yeung, L.; Nassif, N.; Nicholson, G.A. The correlation of clinical phenotype in Friedreich ataxia with the site of point mutations in the FRDA gene. Neurogenetics 1998, 1, 253–257.

- Bidichandani, S.I.; Ashizawa, T.; Patel, P.I. Atypical Friedreich ataxia caused by compound heterozygosity for a novel missense mutation and the GAA triplet-repeat expansion. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1997, 60, 1251–1256.

- Clark, E.; Butler, J.S.; Isaacs, C.J.; Napierala, M.; Lynch, D.R. Selected missense mutations impair frataxin processing in Friedreich ataxia. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2017, 4, 575–584.

- Rufini, A.; Fortuni, S.; Arcuri, G.; Condo, I.; Serio, D.; Incani, O.; Malisan, F.; Ventura, N.; Testi, R. Preventing the ubiquitin-proteasome-dependent degradation of frataxin, the protein defective in Friedreich’s ataxia. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011, 20, 1253–1261.

- Faggianelli, N.; Puglisi, R.; Veneziano, L.; Romano, S.; Frontali, M.; Vannocci, T.; Fortuni, S.; Testi, R.; Pastore, A. Analyzing the Effects of a G137V Mutation in the FXN Gene. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2015, 8, 66.

- Sanfelice, D.; Puglisi, R.; Martin, S.R.; Di Bari, L.; Pastore, A.; Temussi, P.A. Yeast frataxin is stabilized by low salt concentrations: Cold denaturation disentangles ionic strength effects from specific interactions. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e95801.

- Adinolfi, S.; Nair, M.; Politou, A.; Bayer, E.; Martin, S.; Temussi, P.; Pastore, A. The factors governing the thermal stability of frataxin orthologues: How to increase a protein’s stability. Biochemistry 2004, 43, 6511–6518.

- Al-Mahdawi, S.; Pook, M.; Chamberlain, S. A novel missense mutation (L198R) in the Friedreich’s ataxia gene. Hum. Mutat. 2000, 16, 95.

- Faraj, S.E.; Roman, E.A.; Aran, M.; Gallo, M.; Santos, J. The alteration of the C-terminal region of human frataxin distorts its structural dynamics and function. FEBS J. 2014, 281, 3397–3419.

- Faraj, S.E.; Gonzalez-Lebrero, R.M.; Roman, E.A.; Santos, J. Human Frataxin Folds Via an Intermediate State. Role of the C-Terminal Region. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 20782.

- Sacca, F.; Marsili, A.; Puorro, G.; Antenora, A.; Pane, C.; Tessa, A.; Scoppettuolo, P.; Nesti, C.; Brescia Morra, V.; De Michele, G.; et al. Clinical use of frataxin measurement in a patient with a novel deletion in the FXN gene. J. Neurol. 2013, 260, 1116–1121.

- Sacca, F.; Marsili, A.; Puorro, G.; Antenora, A.; Pane, C.; Tessa, A.; Scoppettuolo, P.; Nesti, C.; Brescia Morra, V.; De Michele, G.; et al. Clinical use of frataxin measurement in a patient with a novel deletion in the FXN gene. J. Neurol. 2013, 260, 1116–1121.