The synthesis of ZrO2—CeO2 ceramics was carried out using solid-phase mechanochemical synthesis followed by thermal sintering of the obtained mixtures. ZrO2 and CeO2 powders in equal mole fractions (0.5:0.5) were chosen as initial components for synthesis.

- oxide ceramics

- inert matrices

- phase transformations

1. Introduction

2. ZrO2—CeO2 Ceramics Doped with Yttrium

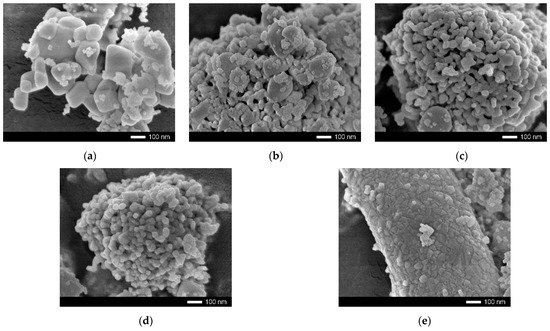

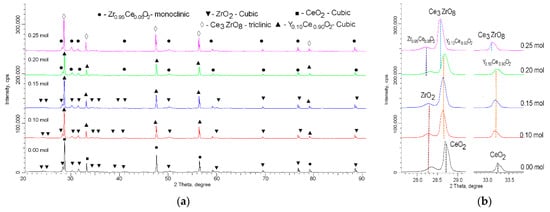

Figure 1 shows the results of the morphological changes in the synthesized ceramics, depending on the dopant concentration. In the case of the undoped ceramics, the particle shape was cubic or diamond-shaped grains, the size of which varied from 50 nm to several hundred nanometers. At the same time, most of the grains were agglomerates consisting of 5–10 grains stuck together. In the case of the doped ceramics, there were clear changes in the morphology and particle size, and the changes were directly dependent on the concentration of the dopant. At a dopant concentration of 0.10 mol, the structure exhibited small spherical grains, which were combined with larger grains to form agglomerates. At a dopant concentration of 0.15 mol, large grains were practically not observed, and the particles were porous formations of small grains. In the case of an increase in the dopant concentration to 0.20–0.25 mol, compaction of the agglomerates was observed, and at a concentration of 0.25 mol, the structure was dense agglomerates without visible cavities between the grains. This behavior may have been due to a change in the phase composition of the ceramics, depending on the dopant concentration, which led to a change in the nucleation processes upon annealing.

References

- Lombardi, C.; Luzzi, L.; Padovani, E.; Vettraino, F. Thoria and inert matrix fuels for a sustainable nuclear power. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2008, 50, 944–953.

- Ledergerber, G.; Degueldre, C.; Heimgartner, P.; Pouchon, M.; Kasemeyer, U. Inert matrix fuel for the utilisation of plutonium. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2001, 38, 301–308.

- Nandi, C.; Grover, V.; Bhandari, K.; Bhattacharya, S.; Mishra, S.; Banerjee, J.; Prakash, A.; Tyagi, A. Exploring YSZ/ZrO2—PuO2 systems: Candidates for inert matrix fuel. J. Nucl. Mater. 2018, 508, 82–91.

- Golovkina, L.S.; Orlova, A.I.; Nokhrin, A.V.; Boldin, M.S.; Lantsev, E.A.; Chuvil’deev, V.N.; Sakharov, N.V.; Shotin, S.V.; Zelenov, A.Y. Spark Plasma Sintering of fine-grained ceramic-metal composites YAG: Nd-(W, Mo) based on garnet-type oxide Y2.5Nd0.5Al5O12 for inert matrix fuel. J. Nucl. Mater. 2018, 511, 109–121.

- Ang, C.; Snead, L.; Kato, Y. A logical approach for zero-rupture Fully Ceramic Microencapsulated (FCM) fuels via pressure-assisted sintering route. J. Nucl. Mater. 2020, 531, 151987.

- Savchyn, V.P.; Popov, A.I.; Aksimentyeva, O.I.; Klym, H.; Horbenko, Y.Y.; Serga, V.; Moskina, A.; Karbovnyk, I. Cathodoluminescence characterization of polystyrene-BaZrO3 hybrid composites. Low Temp. Phys. 2016, 42, 597–600.

- Van Vuuren, A.J.; Skuratov, V.; Ibrayeva, A.; Zdorovets, M. Microstructural Effects of Al Doping on Si3N4 Irradiated with Swift Heavy Ions. Acta Phys. Pol. A 2019, 136, 241–244.

- Settar, A.; Abboudi, S.; Lebaal, N. Effect of inert metal foam matrices on hydrogen production intensification of methane steam reforming process in wall-coated reformer. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 12386–12397.

- Manara, D.; Naji, M.; Mastromarino, S.; Elorrieta, J.; Magnani, N.; Martel, L.; Colle, J.-Y. The Raman fingerprint of plutonium dioxide: Some example applications for the detection of PuO2 in host matrices. J. Nucl. Mater. 2018, 499, 268–271.

- Mikhailov, D.A.; Orlova, A.I.; Malanina, N.V.; Nokhrin, A.V.; Potanina, E.A.; Chuvil’deev, V.N.; Boldin, M.S.; Sakharov, N.V.; Belkin, O.A.; Kalenova, M.Y.; et al. A study of fine-grained ceramics based on complex oxides ZrO2-Ln2O3 (Ln = Sm, Yb) obtained by Spark Plasma Sintering for inert matrix fuel. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 18595–18608.

- Monge, M.A.; González, R.; Muñoz Santiuste, J.E.; Pareja, R.; Chen, Y.; Kotomin, E.A.; Popov, A.I. Photoconversion and dynamic hole recycling process in anion vacancies in neutron-irradiated MgO crystals. Phys. Rev. B 1999, 60, 3787–3791.

- Monge, M.A.; González, R.; Muñoz-Santiuste, J.E.; Pareja, R.; Chen, Y.; Kotomin, E.; Popov, A. Photoconversion of F+ centers in neutron-irradiated MgO. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. At. 2000, 166, 220–224.

- Kadyrzhanov, K.K.; Tinishbaeva, K.; Uglov, V.V. Investigation of the effect of exposure to heavy Xe22+ ions on the mechanical properties of carbide ceramics. Eurasian Phys. Tech. J. 2021, 17, 46–53.

- Popov, A.; Lushchik, A.; Shablonin, E.; Vasil’Chenko, E.; Kotomin, E.; Moskina, A.; Kuzovkov, V. Comparison of the F-type center thermal annealing in heavy-ion and neutron irradiated Al2O3 single crystals. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. At. 2018, 433, 93–97.

- Degueldre, C.; Hellwig, C. Study of a zirconia based inert matrix fuel under irradiation. J. Nucl. Mater. 2003, 320, 96–105.

- Chauvin, N.; Konings, R.; Matzke, H. Optimisation of inert matrix fuel concepts for americium transmutation. J. Nucl. Mater. 1999, 274, 105–111.

- Vu, T.M.; Hartanto, D.; Chu, T.N.; Pham, N.V.H.; Bui, T.H. Sensitivity and uncertainty analysis of neutronic and kinetic parameters for CERCER and CERMET fueled ADS using SERPENT 2 and ENDF/B-VIII.0. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2021, 168, 108912.

- Costa, D.R.; Liu, H.; Lopes, D.A.; Middleburgh, S.C.; Wallenius, J.; Olsson, P. Interface interactions in UN-X-UO2 systems (X= V, Nb, Ta, Cr, Mo, W) by pressure-assisted diffusion experiments at 1773 K. J. Nucl. Mater. 2022, 561, 153554.

- Alin, M.; Kozlovskiy, A.L.; Zdorovets, M.V.; Uglov, V.V. Study of the mechanisms of the t-ZrO2→ c-ZrO2 type polymorphic transformations in ceramics as a result of irradiation with heavy Xe22+ ions. Solid State Sci. 2022, 123, 106791.

- Ivanov, I.A.; Alin, M.; Koloberdin, M.V.; Sapar, A.; Kurakhmedov, A.E.; Kozlovskiy, A.L.; Zdorovets, M.V.; Uglov, V.V. Effect of irradiation with heavy Xe22+ ions with energies of 165–230 MeV on change in optical characteristics of ZrO2 ceramic. Opt. Mater. 2021, 120, 111479.

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, H.X.; Duan, L.; Fan, J.B.; Ni, L.; Ji, V. A comparison study of the structural and mechanical properties of cubic, tetragonal, monoclinic, and three orthorhombic phases of ZrO2. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 749, 283–292.

- Aksimentyeva, O.I.; Savchyn, V.P.; Dyakonov, V.P.; Piechota, S.; Horbenko, Y.Y.; Opainych, I.Y.; Demchenko, P.Y.; Popov, A.; Szymczak, H. Modification of Polymer-Magnetic Nanoparticles by Luminescent and Conducting Substances. Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 2014, 590, 35–42.

- Kim, S.-E.; Yoon, J.-K.; Shon, I.-J. Mechanochemical Synthesis and Rapid Consolidation of Nanostructured Nb-ZrO2 Composite. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2020, 20, 4253–4256.

- Shelyug, A.; Navrotsky, A. Thermodynamic stability of the fluorite phase in the CeO2− CaO− ZrO2 system. J. Nucl. Mater. 2019, 517, 80–85.

- Kumar, R.; Chauhan, V.; Gupta, D.; Upadhyay, S.; Ram, J.; Kumar, S. Advancement of High–k ZrO2 for Potential Applications: A Review. Indian J. Pure Appl. Phys. (IJPAP) 2021, 59, 811–826.

- Alekseeva, L.S.; Nokhrin, A.V.; Boldin, M.S.; Lantsev, E.A.; Orlova, A.I.; Chuvil’Deev, V.N.; Sakharov, N.V. Preparation of Fine-Grained CeO2–SiC Ceramics for Inert Fuel Matrices by Spark Plasma Sintering. Inorg. Mater. 2020, 56, 1307–1313.

- Hudák, I.; Skryja, P.; Bojanovský, J.; Jegla, Z.; Krňávek, M. The Effect of Inert Fuel Compounds on Flame Characteristics. Energies 2021, 15, 262.

- Mareš, K.V.; John, J. Recycling of isotopically modified molybdenum from irradiated CerMet nuclear fuel: Part 1—concept design and assessment. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2019, 320, 227–233.

- Baron, R.; Wejrzanowski, T.; Milewski, J.; Szablowski, L.; Szczęśniak, A.; Fung, K.-Z. Manufacturing of γ -LiAlO2 matrix for molten carbonate fuel cell by high-energy milling. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 6696–6700.

- Sharma, S.K.; Grover, V.; Tyagi, A.; Avasthi, D.; Singh, U.; Kulriya, P. Probing the temperature effects in the radiation stability of Nd2Zr2O7 pyrochlore under swift ion irradiation. Materialia 2019, 6, 100317.

- Mistarihi, Q.M.; Park, W.; Nam, K.; Yahya, M.-S.; Kim, Y.; Ryu, H.J. Fabrication of oxide pellets containing lumped Gd2O3 using Y2O3-stabilized ZrO2 for burnable absorber fuel applications. Int. J. Energy Res. 2018, 42, 2141–2151.

- Wen, T.; Yuan, L.; Tian, C.; Yan, Z.; Liu, Z.; Yu, J. Electrical conductivity behavior of ZrO2-MgO-Y2O3 ceramic: Effect of heat treatment temperature. J. Aust. Ceram. Soc. 2022, 1–7.

- Marek, I.O.; Dudnik, O.V.; Korniy, S.A.; Red’ko, V.P.; Danilenko, M.I.; Ruban, O.K. Effect of Heat Treatment in the Temperature Range 400−1300 °C on the Properties of Nanocrystalline ZrO2− Y2O3− CeO2 Powders. Powder Metall. Met. Ceram. 2022, 60, 1–11.