Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Jessie Wu and Version 3 by Jessie Wu.

Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) is a malignant adenocarcinoma characterized by biliary tract differentiation and is the second most common primary liver tumor.

- cholangiocarcinoma (CCA)

- mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK)

1. The MAPK Signaling Pathways: ERK1/2, JNK-1/2/3, and p38

There are at least three different MAPK signal transduction pathways that modulate and transduce extracellular signals into the nucleus to induce response genes in mammalian cells including ERK1/2, c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase(JNK)1/2/3, and p38 [1][2]. The ERK kinase family is composed of ERK1 (p44) and ERK2 (p42). The JNK kinase family is composed of JNK1, JNK2, and JNK3. Finally, the p38 MAPKs family can be further divided into two subgroups, p38α and p38β, and p38γ and p38δ, respectively [3][4]. In addition, there are other atypical MAPKs that have unique regulation and function including ERK3/4, ERK7/8, and Nemo-like kinase (NLK) [1][2][5][6].

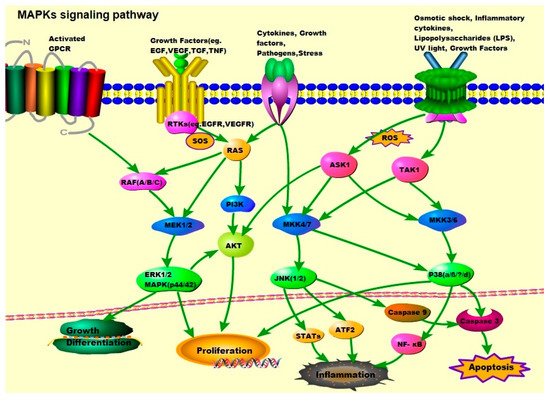

Growth factor-initiated signaling is associated with the ERK pathway, whereas the JNK and p38 pathways are activated by cytokines, growth factors, environmental stress, and other stimuli (Figure 1). In the p38 pathway, MKK3/6 acts as mitogen-activated protein kinase kinases (MAP2Ks) and is activated by mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinases (MAP3Ks) such as apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1), transforming growth factor-β-activated kinase 1 (TAK1), mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 1 (MEKK1), and mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 11 (MLK3). These MAP3Ks also play a role in the JNK pathway, where they target MAP2Ks such as MAP kinase 4 (MKK4)/MAP kinase 7 (MKK7), which activate JNK1/2. In the ERK signaling pathway, ERK1/2 is activated by MEK1/2 and activated by RAF, which is activated by RAS, and RAS is related to the plasma membrane by activation of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR), and platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) [1][7].

Figure 1. MAPK signaling pathway: ERK1/2, JNK1/2, and p38. Activation of ERK begins with the phosphorylation of MEK1/2, followed by activation of tyrosine and threonine residues. Activated RAF binds to and phosphorylates the kinases MEK1/2 as well as activated RAS. The RAS activation occurs at the plasma membrane and is mediated by son of sevenless (SOS), a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF). Signals from cell surface receptors are passed through RAS-GTP to the RAF(A/B/C) and/or PI3K, the latter then activates the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. RAF also receives signals from the activated ligands’ G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). Activated RAF is capable of phosphorylating MEK, and subsequently, the ERK/MAPK signaling pathway. After activation of ERK, ERK1/2 moves to the cytoplasm and nucleus to phosphorylate other proteins. These proteins are responsible for cell regulation, growth, differentiation, and mitosis. JNK is activated in response to cytokines, growth factors, pathogens, stress, etc., and is associated with the transformation of oncogenes and growth factor pathways. Activation of JNK requires dual phosphorylation tyrosine and threonine, the MAP2Ks that catalyze this reaction are known as MKK4 (also known as SEK1) and MKK7. MKK4/7 are phosphorylated and activated by MAP3Ks, TAK1, and ASK1. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor signaling and ROS might be the major upstream mediators of JNK activation. Abnormal activation of the JNK signaling pathway is linked to the development of cancer, diabetes, inflammatory diseases, and neurodegenerative diseases. The activation of p38 is mediated by upstream kinases, MAP kinase 3 (MKK3), and MAP kinase 6 (MKK6). MKK3/6 are activated by MAP3Ks such as ASK1 and TAK1, which respond to various extracellular stimuli including osmotic shock, inflammatory cytokines, lipopolysaccharides (LPS), UV light, and growth factors.

1.1. JNK/MAPKs

In normal liver, the JNK family is minimally or transiently activated, the latter usually physiological, whereas sustained activation is pathological. In addition to their central role in hepatic physiological responses (such as cell death, apoptosis, and cell cycle regulation) [8][9], JNK plays a carcinogenic role by promoting inflammation, proliferation, invasion, and angiogenesis, depending on the specific context and duration of the activation of the JNK signaling pathway [10][11]. Earlier studies have reported that the JNK signaling pathway plays a significant role in the development of HCC [12][13]. In particular, Jnk1 seems to be more important in malignant transformation and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) development [14][15]. However, during the progression of liver disease, the deletion of Jnk1 significantly exacerbated apoptosis, compensatory proliferation, and carcinogenesis in experimental chronic liver disease. In turn, Jnk2 was reported to modulate necrosis and inflammation [16]. Using Puma KO mice in diethylnitrosamine (DEN)-induced HCC, HCC formation was suppressed, a phenomenon associated with reduced cell death and compensatory proliferation of hepatocytes. However, such effects were inhibited by the administration of the JNK inhibitor SP600125 [17]. In human HCC cell lines, Jnk1 activation is associated with tumor size. By knocking down Jnk1 but not Jnk2, proliferation of human HCC occurs via upregulation of cmyc and downregulation of p21 [18].

The JNK signaling pathway has been recently implicated in CCA development. JNK plays an important role in regulating the interaction between different pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic proteins in response to both external and internal apoptotic stimuli [19]. In human CCA, a high expression of TNFA in cells near CCA lesions was found and phosphorylation of JNK in cholangiocytes (80% in CCA patients) as well as the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) around the peripheral hepatocytes occurred. Accumulation of ROS leads to caspase-3-dependent apoptosis via JNK. At the same time, Yuan et al. [20], showed that mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress promoted cholangiocellular overgrowth and tumorigenesis. In this study, cholangiocellular proliferation and oncogenic transformation were promoted through the JNK signaling pathway, which was activated by Kupffer cells (KC), subsequently leading to liver damage, ROS, and the paracrine release of TNF. Therefore, KC-derived TNF might promote cholangiocellular cell proliferation, differentiation, and carcinogenesis, suggesting that the ROS/TNF/JNK axis plays a significant role in the development of CCA. Another study that tested the antioxidant activity of using guggulsterone, a steroid found in the resin of the guggul plant (Commiphora wightii) in both HuCC-T1 and RBE CCA cell lines, showed that guggulsterone could induce the apoptosis of human CCA cells via ROS-mediated activation of the JNK signaling pathway [21]. Feng et al. [22] reported that JNK exerted its carcinogenic effect in human CCA cells, partially because the mammalian target of the rapamycin (mTOR) pathway was regulated by the induction of glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78). They showed that eukaryotic initiation factor-α (eIF2a)/activated transcription factor 4 (ATF4) signaling promoted the accumulation of GRP78; whilst JNK was both promoted by the activation of mTOR and characterized by a high expression of GRP78. These results indicated that GRP78 contributed to the pro-tumorigenic function of JNK in human CCA cells, partly through promoting the eIF2α/ATF4/GRP78 pathway, and through JNK/mTOR signaling. As above-mentioned, the JNK/MAPKs signaling pathway may be a key target in the treatment of CCA; however, more studies are needed to test this possibility.

1.2. p38/MAPKs

The p38 kinase plays a key role by promoting proliferation, invasion, inflammation, and angiogenesis in the occurrence and development of CCA [23][24][25][26], also affecting the growth of malignant human CCA cells, and maintaining the phenotype of transformed cells [26][27]. p38δ can be used for differential diagnosis of CCA, since it is not expressed in HCC cells [28]. IL-6 receptors and tyrosine kinases receptors such as Met (c-MET) and the EGFR family members ERBB2 and ERBB1 (EGFR) are key signaling pathways in CCA. Members of the EGFR family, particularly EGFR and ERBB2 (HER-2/neu), are involved in the pathogenesis of CCA [29][30][31]. Dai et al. [32] reported that both p38 and C-MET, the tyrosine kinase receptor for hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), promote the proliferation and invasion of human CCA cells, and p38 promotes CCA formation via sustained activation of C-MET. In addition, using ATO (arsenic trioxide) alone or in combination with metformin to treat CCA cell lines, Ling et al. [23] found that inactivation of p38 by the inhibitor SB203580 or specific siRNA could enhance the anticancer efficacy of single drug or combination of metformin and ATO, especially using ATO alone. Furthermore, the expression of P38δ was upregulated in CCA when compared to normal biliary tissue. Inhibition of P38δ expression by siRNA transfection significantly reduced CCA cell proliferation and invasion. Conversely, overexpression of P38δ in CCA cells can induce an increase in tumor invasiveness.

1.3. ERK/MAPKs

Previous studies have reported an upregulation of the RAS-ERK1/2 signaling pathway in CCA [33]. TGF-β transmits signals through SMAD2/3 phosphorylation, but can also transduce signals via RAS-ERK1/2, PI3K, p38, and Rho pathways [34][35][36]. Rac1, a member of the Rho family of small GTPases, plays a pivotal role in the development of CCA [37][38]. Li et al. [39] demonstrated that integrin β6 promoted tumor cell malignant behavior by activating Rac1. In biliary dysplasia, hyperplasia and CCA, TGF-β is overexpressed, a mechanism associated with CCA initiation and formation [33][40][41]. Moreover, ERK1/2 activation has also been linked with TGF-β-induced epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) and cell invasiveness. One study using CCA cell lines indicated that TGF-β enhanced cell invasiveness and mesenchymal features in CCA cell lines [40]. Recently, a study using CCA cell lines (KKU-M213 and HuCCA-1) showed that TGF-β activates ERK1/2 via the SMAD2/3 pathway, enhancing TGF-β activity to promote tumor growth [42]. As above-mentioned, TGF-β can also transduce signals via the RAS-ERK/PI3K pathways [34][35][36]. The PI3K/AKT/PTEN signaling pathway is significantly overexpressed in human CCA tissue [43], therefore it is another important pathway involved in the development of CCA associated with RAS/ERK/MAPKs. PI3K is one of the most important factors in RAS activation and can be involved in the regulation of various functions including cell growth, cell cycle entry, cell survival, cytoskeleton reorganization, and apoptosis [29][44][45] (Figure 1). Loss of phosphatase function of PTEN will result in the constitutive activation of (PI3K/protein kinase B) AKT signaling pathway in CCA. Inhibition of PI3K/AKT signaling effectively blocked the proliferation and invasive behavior of CCA [43]. At the same time, Hyunho et al. [46] using CCA cell lines (SCK and Choi-CK) with inactivation of AKT, showed decreased expression of BCL2, and enhanced expression of BAX, thereby inducing the apoptosis of resistant cells; whilst the inhibition of ERK1/2 activation did not induce apoptosis, but decreased tumor cell growth. These results indicated that the AKT/ERK1/2 signaling transduction pathway might mediate apoptosis in CCA cell lines. Furthermore, in CCA, the expression of the HGF receptor (HGFR) encoded by the MET gene, also known as cMET, is increased (12–58%). Activation of MET promotes cell invasion and triggers metastasis by directly participating in tumor angiogenesis [47]. Experiments with CCA cell lines indicate that HGFR-dependent CCA cell invasiveness occurs via the AKT/ERK signaling pathway [48][49][50]. In summary, abundant evidence suggests that the ERK signaling pathway is intimately related to cholangiocarcinogenesis. In the future, the ERK signaling pathway may be an effective target for the diagnosis and treatment of CCA; however, more research is needed to confirm this.

1.4. ‘Other’ Kinases

Kinases such as transforming growth factor-β-activated kinase 1 (TAK1) belong to the MAP3Ks family. TAK1 is activated in response to cytokines such as TNF, LPS, and TGF-β in multiple cellular systems [51]. Activation of the TGF-β receptor triggers downstream signaling mediated by SMAD family of proteins, which promotes EMT progression in CCA (discussed below). However, phosphorylated TAK1 activates IKK (IκB kinase) and MKK4/7, causing the activation of NF-κB and JNK. Deletion of TAK1 in liver parenchymal cells (both hepatocytes and cholangiocytes) promotes hepatocyte death, inflammation, fibrosis, and hepatocarcinogenesis, coinciding with biliary ductopenia and cholestasis [52][53][54]. ASK1 is another member of the MAPK family, known as MAP3K5 (mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 5), which can activate the P38 and JNK pathways in response to both oxidative and ER (endoplasmic reticulum) stress as well as stress-induced via inflammatory cytokines (such as TNFα) [55][56][57].

2. Biomarkers and Diagnosis

The development of CCA involves genetic alterations of related oncogenes in humans [58][59][60][61][62][63][64][65] (Table 1). Mutations common to tumors all along the chromosome include tumor suppressor genes (TP53, and PTEN), chromatin-remodeling genes (ARID1A, ARID1B, BAP1, PBRM1), and gain of function of oncogenes (KRAS, BRAF, and PIK3CA). However, mutations in the ERK/MAPKs pathway components are relatively common in CCA. In particular, KRAS mutations are associated with a decrease in both progression-free, and overall survival in CCA patients [66]. KRAS activating mutations are frequently detected (22%, range 5–57%) [67][68][69], especially in codon 12 hotspots, and have recently been identified as an independent predictor of poor survival after surgery [69][70].Table 1.

Genetic alterations of related oncogenes in human CCA.

| Oncogenes | Tumor Suppressor Genes | Chromatin-Remodeling Genes | Gain of Function of Oncogenes |

|---|---|---|---|

| MLL3 | TP53 | ARID1A | KRAS |

| ROBO2 | PTEN | ARID1B | BRAF |

| RNF43 | BAP1 | PIK3CA | |

| PEG3 | PBRM1 | ||

| GNAS | |||

| NRAS | |||

| PTPN3 | |||

| CDKN2A | |||

| SMAD4 | |||

| IDH1/2 |

Oncogenes in humans CCA include KMT2C (lysine methyltransferase 2C), roundabout guidance receptor 2 (ROBO2), ring finger protein 43 (RNF43), paternally expressed 3 (PEG3), guanine nucleotide binding protein (G protein) alpha stimulating activity polypeptide 1 (GNAS), (BRCA-associated protein 1 (BAP1), V-Ki-ras2 Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS), neuroblastoma RAS viral (v-ras) oncogene homolog (NRAS), v-raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1 (BRAF), polybromo 1 (PBRM1), AT rich interactive domain 1A (SWI-like) (ARID1A), AT-rich interaction domain 1B (ARID1B); phosphoinositide-3-kinase, catalytic, alpha polypeptide (PIK3CA), phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome ten (PTEN), protein tyrosine phosphatase non-receptor type 3 (PTPN3), cyclin dependent kinase 2a/p16 (CDKN2A), mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 4 (Drosophila) (SMAD4), tumor protein p53 (TP53), isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1), and isocitrate dehydrogenase 2 (IDH2).

3. Surgical Treatment

Currently, surgical resection is still the preferred treatment for CCA. However, only a small number of patients (about 35%) are diagnosed sufficiently early to undergo surgery [81]. In 2012, the 5-year survival rates of surgically treated CCA, iCCA, pCCA, and dCCA were 22–44%, 11–41%, and 27–37%, respectively [82]. However, a recent study including 574 patients with pCCA that underwent right hepatic artery resection and reconstruction, with a perioperative mortality rate of less than 5%, showed a 5-year survival rate of 30% [83]. Contraindications to CCA surgical resection include bilateral, multifocal disease, distant metastases, and comorbidities associated with surgical risk that exceed the patient’s expected surgical benefits. Regional lymph node metastasis is not considered an absolute contraindication to resection, although N1 disease (CCA with regional lymph node metastases including nodes along the cystic duct, common bile duct, hepatic artery, and portal vein) is one of the prognostic factors representing poor prognosis [84][85][86]. Although Bismuth-Corlette type IV pCCA is not considered to be an absolute contraindication to surgical resection, subsequent orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) is a valid treatment after neoadjuvant radiotherapy [87]. The recurrence rate was 20% and the 5-year survival rate was 68% [87]. However, the selection criteria were strict and 25% to 31% of patients developed disease progression while waiting for OLT and were excluded from the protocol [86][87]. Therefore, single-OLT is not recommended as a CCA monotherapy because of high recurrence rates and long-term survival rates of less than 20% [88][89]. Current guidelines for CCA are still controversial, but due to regional differences between Eastern and Western centers, different surgical resection criteria and surgical strategies are based on applied areas, especially between the Western (US and Europe) and the Eastern centers, with aggressive surgical procedures (including extended hepatectomy and combination with vascular resection in early pCCA). Thus, the actual resection rate of CCA patients has increased, and the prognosis improved in East Asia [83][90][91].References

- Cargnello, M.; Roux, P.P. Activation and function of the mapks and their substrates, the mapk-activated protein kinases. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2011, 75, 50–83.

- Johnson, G.L.; Lapadat, R. Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways mediated by erk, jnk, and p38 protein kinases. Science 2002, 298, 1911–1912.

- Brancho, D.; Tanaka, N.; Jaeschke, A.; Ventura, J.J.; Kelkar, N.; Tanaka, Y.; Kyuuma, M.; Takeshita, T.; Flavell, R.A.; Davis, R.J. Mechanism of p38 map kinase activation in vivo. Genes Dev. 2003, 17, 1969–1978.

- Remy, G.; Risco, A.M.; Inesta-Vaquera, F.A.; Gonzalez-Teran, B.; Sabio, G.; Davis, R.J.; Cuenda, A. Differential activation of p38mapk isoforms by mkk6 and mkk3. Cell. Signal. 2010, 22, 660–667.

- Bubici, C.; Papa, S. Jnk signalling in cancer: In need of new, smarter therapeutic targets. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 171, 24–37.

- Mao, X.; Bravo, I.G.; Cheng, H.; Alonso, A. Multiple independent kinase cascades are targeted by hyperosmotic stress but only one activates stress kinase p38. Exp. Cell. Res. 2004, 292, 304–311.

- Roberts, P.J.; Der, C.J. Targeting the raf-mek-erk mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade for the treatment of cancer. Oncogene 2007, 26, 3291–3310.

- Win, S.; Than, T.A.; Zhang, J.; Oo, C.; Min, R.W.M.; Kaplowitz, N. New insights into the role and mechanism of c-jun-n-terminal kinase signaling in the pathobiology of liver diseases. Hepatology 2018, 67, 2013–2024.

- Win, S.; Than, T.A.; Min, R.W.; Aghajan, M.; Kaplowitz, N. C-jun n-terminal kinase mediates mouse liver injury through a novel sab (sh3bp5)-dependent pathway leading to inactivation of intramitochondrial src. Hepatology 2016, 63, 1987–2003.

- Mingo-Sion, A.M.; Marietta, P.M.; Koller, E.; Wolf, D.M.; Van Den Berg, C.L. Inhibition of jnk reduces g2/m transit independent of p53, leading to endoreduplication, decreased proliferation, and apoptosis in breast cancer cells. Oncogene 2004, 23, 596–604.

- Vivanco, I.; Palaskas, N.; Tran, C.; Finn, S.P.; Getz, G.; Kennedy, N.J.; Jiao, J.; Rose, J.; Xie, W.; Loda, M.; et al. Identification of the jnk signaling pathway as a functional target of the tumor suppressor pten. Cancer Cell 2007, 11, 555–569.

- Wang, J.; Tai, G. Role of c-jun n-terminal kinase in hepatocellular carcinoma development. Target. Oncol. 2016, 11, 723–738.

- Cubero, F.J.; Zhao, G.; Nevzorova, Y.A.; Hatting, M.; Al Masaoudi, M.; Verdier, J.; Peng, J.; Schaefer, F.M.; Hermanns, N.; Boekschoten, M.V.; et al. Haematopoietic cell-derived jnk1 is crucial for chronic inflammation and carcinogenesis in an experimental model of liver injury. J. Hepatol. 2015, 62, 140–149.

- Chen, F. Jnk-induced apoptosis, compensatory growth, and cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 379–386.

- Seki, E.; Brenner, D.A.; Karin, M. A liver full of jnk: Signaling in regulation of cell function and disease pathogenesis, and clinical approaches. Gastroenterology 2012, 143, 307–320.

- Cazanave, S.C.; Mott, J.L.; Elmi, N.A.; Bronk, S.F.; Werneburg, N.W.; Akazawa, Y.; Kahraman, A.; Garrison, S.P.; Zambetti, G.P.; Charlton, M.R.; et al. Jnk1-dependent puma expression contributes to hepatocyte lipoapoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 26591–26602.

- Qiu, W.; Wang, X.; Leibowitz, B.; Yang, W.; Zhang, L.; Yu, J. Puma-mediated apoptosis drives chemical hepatocarcinogenesis in mice. Hepatology 2011, 54, 1249–1258.

- Chang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Beezhold, K.J.; Bhatia, D.; Zhao, H.; Chen, J.; Castranova, V.; Shi, X.; Chen, F. Sustained jnk1 activation is associated with altered histone h3 methylations in human liver cancer. J. Hepatol. 2009, 50, 323–333.

- Dhanasekaran, D.N.; Reddy, E.P. Jnk signaling in apoptosis. Oncogene 2008, 27, 6245–6251.

- Yuan, D.; Huang, S.; Berger, E.; Liu, L.; Gross, N.; Heinzmann, F.; Ringelhan, M.; Connor, T.O.; Stadler, M.; Meister, M.; et al. Kupffer cell-derived tnf triggers cholangiocellular tumorigenesis through jnk due to chronic mitochondrial dysfunction and ros. Cancer Cell 2017, 31, 771–789 e776.

- Zhong, F.; Tong, Z.T.; Fan, L.L.; Zha, L.X.; Wang, F.; Yao, M.Q.; Gu, K.S.; Cao, Y.X. Guggulsterone-induced apoptosis in cholangiocarcinoma cells through ros/jnk signaling pathway. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2016, 6, 226–237.

- Feng, C.; He, K.; Zhang, C.; Su, S.; Li, B.; Li, Y.; Duan, C.Y.; Chen, S.; Chen, R.; Liu, Y.; et al. Jnk contributes to the tumorigenic potential of human cholangiocarcinoma cells through the mtor pathway regulated grp78 induction. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e90388.

- Ling, S.; Xie, H.; Yang, F.; Shan, Q.; Dai, H.; Zhuo, J.; Wei, X.; Song, P.; Zhou, L.; Xu, X.; et al. Metformin potentiates the effect of arsenic trioxide suppressing intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: Roles of p38 mapk, erk3, and mtorc1. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2017, 10, 59.

- Del Barco Barrantes, I.; Nebreda, A.R. Roles of p38 mapks in invasion and metastasis. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2012, 40, 79–84.

- Rousseau, S.; Dolado, I.; Beardmore, V.; Shpiro, N.; Marquez, R.; Nebreda, A.R.; Arthur, J.S.; Case, L.M.; Tessier-Lavigne, M.; Gaestel, M.; et al. Cxcl12 and c5a trigger cell migration via a pak1/2-p38alpha mapk-mapkap-k2-hsp27 pathway. Cell. Signal. 2006, 18, 1897–1905.

- Platanias, L.C. Map kinase signaling pathways and hematologic malignancies. Blood 2003, 101, 4667–4679.

- Yamagiwa, Y.; Marienfeld, C.; Tadlock, L.; Patel, T. Translational regulation by p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling during human cholangiocarcinoma growth. Hepatology 2003, 38, 158–166.

- Tan, F.L.; Ooi, A.; Huang, D.; Wong, J.C.; Qian, C.N.; Chao, C.; Ooi, L.; Tan, Y.M.; Chung, A.; Cheow, P.C.; et al. P38delta/mapk13 as a diagnostic marker for cholangiocarcinoma and its involvement in cell motility and invasion. Int. J. Cancer 2010, 126, 2353–2361.

- Rizvi, S.; Gores, G.J. Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management of cholangiocarcinoma. Gastroenterology 2013, 145, 1215–1229.

- Yoshikawa, D.; Ojima, H.; Iwasaki, M.; Hiraoka, N.; Kosuge, T.; Kasai, S.; Hirohashi, S.; Shibata, T. Clinicopathological and prognostic significance of egfr, vegf, and her2 expression in cholangiocarcinoma. Br. J. Cancer 2008, 98, 418–425.

- Nakazawa, K.; Dobashi, Y.; Suzuki, S.; Fujii, H.; Takeda, Y.; Ooi, A. Amplification and overexpression of c-erbb-2, epidermal growth factor receptor, and c-met in biliary tract cancers. J. Pathol. 2005, 206, 356–365.

- Dai, R.; Li, J.; Fu, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, R.; Zhao, X.; Luo, T.; Zhu, J.; Ren, Y.; Cao, J.; et al. The tyrosine kinase c-met contributes to the pro-tumorigenic function of the p38 kinase in human bile duct cholangiocarcinoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 39812–39823.

- Sia, D.; Tovar, V.; Moeini, A.; Llovet, J.M. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: Pathogenesis and rationale for molecular therapies. Oncogene 2013, 32, 4861–4870.

- Papadimitriou, E.; Vasilaki, E.; Vorvis, C.; Iliopoulos, D.; Moustakas, A.; Kardassis, D.; Stournaras, C. Differential regulation of the two rhoa-specific gef isoforms net1/net1a by tgf-beta and mir-24: Role in epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Oncogene 2012, 31, 2862–2875.

- Olieslagers, S.; Pardali, E.; Tchaikovski, V.; ten Dijke, P.; Waltenberger, J. Tgf-beta1/alk5-induced monocyte migration involves pi3k and p38 pathways and is not negatively affected by diabetes mellitus. Cardiovasc. Res. 2011, 91, 510–518.

- Chapnick, D.A.; Warner, L.; Bernet, J.; Rao, T.; Liu, X. Partners in crime: The tgfbeta and mapk pathways in cancer progression. Cell Biosci. 2011, 1, 42.

- Miller, T.; Yang, F.; Wise, C.E.; Meng, F.; Priester, S.; Munshi, M.K.; Guerrier, M.; Dostal, D.E.; Glaser, S.S. Simvastatin stimulates apoptosis in cholangiocarcinoma by inhibition of rac1 activity. Dig. Liver Dis. 2011, 43, 395–403.

- Cadamuro, M.; Nardo, G.; Indraccolo, S.; Dall’olmo, L.; Sambado, L.; Moserle, L.; Franceschet, I.; Colledan, M.; Massani, M.; Stecca, T.; et al. Platelet-derived growth factor-d and rho gtpases regulate recruitment of cancer-associated fibroblasts in cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology 2013, 58, 1042–1053.

- Li, Z.; Biswas, S.; Liang, B.; Zou, X.; Shan, L.; Li, Y.; Fang, R.; Niu, J. Integrin beta6 serves as an immunohistochemical marker for lymph node metastasis and promotes cell invasiveness in cholangiocarcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 30081.

- Sato, Y.; Harada, K.; Itatsu, K.; Ikeda, H.; Kakuda, Y.; Shimomura, S.; Shan Ren, X.; Yoneda, N.; Sasaki, M.; Nakanuma, Y. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition induced by transforming growth factor-1/snail activation aggravates invasive growth of cholangiocarcinoma. Am. J. Pathol. 2010, 177, 141–152.

- Zen, Y.; Harada, K.; Sasaki, M.; Chen, T.C.; Chen, M.F.; Yeh, T.S.; Jan, Y.Y.; Huang, S.F.; Nimura, Y.; Nakanuma, Y. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma escapes from growth inhibitory effect of transforming growth factor-beta1 by overexpression of cyclin d1. Lab. Investig. 2005, 85, 572–581.

- Sritananuwat, P.; Sueangoen, N.; Thummarati, P.; Islam, K.; Suthiphongchai, T. Blocking erk1/2 signaling impairs tgf-beta1 tumor promoting function but enhances its tumor suppressing role in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma cells. Cancer Cell Int. 2017, 17, 85.

- Yothaisong, S.; Dokduang, H.; Techasen, A.; Namwat, N.; Yongvanit, P.; Bhudhisawasdi, V.; Puapairoj, A.; Riggins, G.J.; Loilome, W. Increased activation of pi3k/akt signaling pathway is associated with cholangiocarcinoma metastasis and pi3k/mtor inhibition presents a possible therapeutic strategy. Tumour Biol. 2013, 34, 3637–3648.

- Kokuryo, T.; Yokoyama, Y.; Nagino, M. Recent advances in cancer stem cell research for cholangiocarcinoma. J. Hepatobil. Pancreat. Sci. 2012, 19, 606–613.

- Utispan, K.; Sonongbua, J.; Thuwajit, P.; Chau-In, S.; Pairojkul, C.; Wongkham, S.; Thuwajit, C. Periostin activates integrin alpha5beta1 through a pi3k/aktdependent pathway in invasion of cholangiocarcinoma. Int. J. Oncol. 2012, 41, 1110–1118.

- Yoon, H.; Min, J.K.; Lee, J.W.; Kim, D.G.; Hong, H.J. Acquisition of chemoresistance in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma cells by activation of akt and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (erk)1/2. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011, 405, 333–337.

- Zhang, Y.W.; Su, Y.; Volpert, O.V.; Vande Woude, G.F. Hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor mediates angiogenesis through positive vegf and negative thrombospondin 1 regulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 12718–12723.

- Miyamoto, M.; Ojima, H.; Iwasaki, M.; Shimizu, H.; Kokubu, A.; Hiraoka, N.; Kosuge, T.; Yoshikawa, D.; Kono, T.; Furukawa, H.; et al. Prognostic significance of overexpression of c-met oncoprotein in cholangiocarcinoma. Br. J. Cancer 2011, 105, 131–138.

- Terada, T.; Nakanuma, Y.; Sirica, A.E. Immunohistochemical demonstration of met overexpression in human intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and in hepatolithiasis. Hum. Pathol. 1998, 29, 175–180.

- Menakongka, A.; Suthiphongchai, T. Involvement of pi3k and erk1/2 pathways in hepatocyte growth factor-induced cholangiocarcinoma cell invasion. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 16, 713–722.

- Rincon, M.; Davis, R.J. Regulation of the immune response by stress-activated protein kinases. Immunol. Rev. 2009, 228, 212–224.

- Bettermann, K.; Vucur, M.; Haybaeck, J.; Koppe, C.; Janssen, J.; Heymann, F.; Weber, A.; Weiskirchen, R.; Liedtke, C.; Gassler, N.; et al. Tak1 suppresses a nemo-dependent but nf-kappab-independent pathway to liver cancer. Cancer Cell 2010, 17, 481–496.

- Malato, Y.; Willenbring, H. The map3k tak1: A chock block to liver cancer formation. Hepatology 2010, 52, 1506–1509.

- Inokuchi, S.; Aoyama, T.; Miura, K.; Osterreicher, C.H.; Kodama, Y.; Miyai, K.; Akira, S.; Brenner, D.A.; Seki, E. Disruption of tak1 in hepatocytes causes hepatic injury, inflammation, fibrosis, and carcinogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 844–849.

- Nygaard, G.; Di Paolo, J.A.; Hammaker, D.; Boyle, D.L.; Budas, G.; Notte, G.T.; Mikaelian, I.; Barry, V.; Firestein, G.S. Regulation and function of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 in rheumatoid arthritis. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2018, 151, 282–290.

- Fujino, G.; Noguchi, T.; Matsuzawa, A.; Yamauchi, S.; Saitoh, M.; Takeda, K.; Ichijo, H. Thioredoxin and traf family proteins regulate reactive oxygen species-dependent activation of ask1 through reciprocal modulation of the n-terminal homophilic interaction of ask1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007, 27, 8152–8163.

- Hattori, K.; Naguro, I.; Runchel, C.; Ichijo, H. The roles of ask family proteins in stress responses and diseases. Cell Commun. Signal. 2009, 7, 9.

- Rizvi, S.; Khan, S.A.; Hallemeier, C.L.; Kelley, R.K.; Gores, G.J. Cholangiocarcinoma—Evolving concepts and therapeutic strategies. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 15, 95–111.

- Hogdall, D.; Lewinska, M.; Andersen, J.B. Desmoplastic tumor microenvironment and immunotherapy in cholangiocarcinoma. Trends Cancer 2018, 4, 239–255.

- Ong, C.K.; Subimerb, C.; Pairojkul, C.; Wongkham, S.; Cutcutache, I.; Yu, W.; McPherson, J.R.; Allen, G.E.; Ng, C.C.; Wong, B.H.; et al. Exome sequencing of liver fluke-associated cholangiocarcinoma. Nat. Genet. 2012, 44, 690–693.

- Jiao, Y.; Pawlik, T.M.; Anders, R.A.; Selaru, F.M.; Streppel, M.M.; Lucas, D.J.; Niknafs, N.; Guthrie, V.B.; Maitra, A.; Argani, P.; et al. Exome sequencing identifies frequent inactivating mutations in bap1, arid1a and pbrm1 in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 1470–1473.

- Macias, R.I.R.; Banales, J.M.; Sangro, B.; Muntane, J.; Avila, M.A.; Lozano, E.; Perugorria, M.J.; Padillo, F.J.; Bujanda, L.; Marin, J.J.G. The search for novel diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers in cholangiocarcinoma. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2018, 1864, 1468–1477.

- Rizvi, S.; Borad, M.J.; Patel, T.; Gores, G.J. Cholangiocarcinoma: Molecular pathways and therapeutic opportunities. Semin. Liver Dis. 2014, 34, 456–464.

- Ross, J.S.; Wang, K.; Gay, L.; Al-Rohil, R.; Rand, J.V.; Jones, D.M.; Lee, H.J.; Sheehan, C.E.; Otto, G.A.; Palmer, G.; et al. New routes to targeted therapy of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas revealed by next-generation sequencing. Oncologist 2014, 19, 235–242.

- Farshidfar, F.; Zheng, S.; Gingras, M.C.; Newton, Y.; Shih, J.; Robertson, A.G.; Hinoue, T.; Hoadley, K.A.; Gibb, E.A.; Roszik, J.; et al. Integrative genomic analysis of cholangiocarcinoma identifies distinct idh-mutant molecular profiles. Cell Rep. 2017, 18, 2780–2794.

- Churi, C.R.; Shroff, R.; Wang, Y.; Rashid, A.; Kang, H.C.; Weatherly, J.; Zuo, M.; Zinner, R.; Hong, D.; Meric-Bernstam, F.; et al. Mutation profiling in cholangiocarcinoma: Prognostic and therapeutic implications. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e115383.

- Sia, D.; Hoshida, Y.; Villanueva, A.; Roayaie, S.; Ferrer, J.; Tabak, B.; Peix, J.; Sole, M.; Tovar, V.; Alsinet, C.; et al. Integrative molecular analysis of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma reveals 2 classes that have different outcomes. Gastroenterology 2013, 144, 829–840.

- Andersen, J.B.; Spee, B.; Blechacz, B.R.; Avital, I.; Komuta, M.; Barbour, A.; Conner, E.A.; Gillen, M.C.; Roskams, T.; Roberts, L.R.; et al. Genomic and genetic characterization of cholangiocarcinoma identifies therapeutic targets for tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Gastroenterology 2012, 142, 1021–1031 e1015.

- Chen, T.C.; Jan, Y.Y.; Yeh, T.S. K-ras mutation is strongly associated with perineural invasion and represents an independent prognostic factor of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma after hepatectomy. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2012, 19 (Suppl. 3), S675–S681.

- Isa, T.; Tomita, S.; Nakachi, A.; Miyazato, H.; Shimoji, H.; Kusano, T.; Muto, Y.; Furukawa, M. Analysis of microsatellite instability, k-ras gene mutation and p53 protein overexpression in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology 2002, 49, 604–608.

- Junttila, M.R.; de Sauvage, F.J. Influence of tumour micro-environment heterogeneity on therapeutic response. Nature 2013, 501, 346–354.

- Jiang, K.; Al-Diffhala, S.; Centeno, B.A. Primary liver cancers-part 1: Histopathology, differential diagnoses, and risk stratification. Cancer Control 2018, 25, 1073274817744625.

- Chan, E.S.; Yeh, M.M. The use of immunohistochemistry in liver tumors. Clin. Liver Dis. 2010, 14, 687–703.

- Bioulac-Sage, P.; Cubel, G.; Taouji, S.; Scoazec, J.Y.; Leteurtre, E.; Paradis, V.; Sturm, N.; Nhieu, J.T.; Wendum, D.; Bancel, B.; et al. Immunohistochemical markers on needle biopsies are helpful for the diagnosis of focal nodular hyperplasia and hepatocellular adenoma subtypes. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2012, 36, 1691–1699.

- Han, C.P.; Hsu, J.D.; Koo, C.L.; Yang, S.F. Antibody to cytokeratin (ck8/ck18) is not derived from cam5.2 clone, and anticytokeratin cam5.2 (becton dickinson) is not synonymous with the antibody (ck8/ck18). Hum. Pathol. 2010, 41, 616–617, author reply 617.

- Razumilava, N.; Gores, G.J. Notch-driven carcinogenesis: The merging of hepatocellular cancer and cholangiocarcinoma into a common molecular liver cancer subtype. J. Hepatol. 2013, 58, 1244–1245.

- Matsushima, H.; Kuroki, T.; Kitasato, A.; Adachi, T.; Tanaka, T.; Hirabaru, M.; Hirayama, T.; Kuroshima, N.; Hidaka, M.; Soyama, A.; et al. Sox9 expression in carcinogenesis and its clinical significance in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Dig. Liver Dis. 2015, 47, 1067–1075.

- Ferrone, C.R.; Ting, D.T.; Shahid, M.; Konstantinidis, I.T.; Sabbatino, F.; Goyal, L.; Rice-Stitt, T.; Mubeen, A.; Arora, K.; Bardeesey, N.; et al. The ability to diagnose intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma definitively using novel branched DNA-enhanced albumin rna in situ hybridization technology. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2016, 23, 290–296.

- Macias, R.I.R.; Kornek, M.; Rodrigues, P.M.; Paiva, N.A.; Castro, R.E.; Urban, S.; Pereira, S.P.; Cadamuro, M.; Rupp, C.; Loosen, S.H.; et al. Diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers in cholangiocarcinoma. Liver Int. 2019, 39, 108–122.

- Forner, A.; Vidili, G.; Rengo, M.; Bujanda, L.; Ponz-Sarvise, M.; Lamarca, A. Clinical presentation, diagnosis and staging of cholangiocarcinoma. Liver Int. 2019, 39, 98–107.

- Jarnagin, W.R.; Fong, Y.; DeMatteo, R.P.; Gonen, M.; Burke, E.C.; Bodniewicz, B.J.; Youssef, B.M.; Klimstra, D.; Blumgart, L.H. Staging, resectability, and outcome in 225 patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann. Surg. 2001, 234, 507–517.

- Khan, S.A.; Davidson, B.R.; Goldin, R.D.; Heaton, N.; Karani, J.; Pereira, S.P.; Rosenberg, W.M.; Tait, P.; Taylor-Robinson, S.D.; Thillainayagam, A.V.; et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cholangiocarcinoma: An update. Gut 2012, 61, 1657–1669.

- Nagino, M.; Ebata, T.; Yokoyama, Y.; Igami, T.; Sugawara, G.; Takahashi, Y.; Nimura, Y. Evolution of surgical treatment for perihilar cholangiocarcinoma: A single-center 34-year review of 574 consecutive resections. Ann. Surg. 2013, 258, 129–140.

- Endo, I.; Gonen, M.; Yopp, A.C.; Dalal, K.M.; Zhou, Q.; Klimstra, D.; D’Angelica, M.; DeMatteo, R.P.; Fong, Y.; Schwartz, L.; et al. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: Rising frequency, improved survival, and determinants of outcome after resection. Ann. Surg. 2008, 248, 84–96.

- Weber, S.M.; Jarnagin, W.R.; Klimstra, D.; DeMatteo, R.P.; Fong, Y.; Blumgart, L.H. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: Resectability, recurrence pattern, and outcomes. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2001, 193, 384–391.

- Blechacz, B. Cholangiocarcinoma: Current knowledge and new developments. Gut Liver 2017, 11, 13–26.

- Darwish Murad, S.; Kim, W.R.; Therneau, T.; Gores, G.J.; Rosen, C.B.; Martenson, J.A.; Alberts, S.R.; Heimbach, J.K. Predictors of pretransplant dropout and posttransplant recurrence in patients with perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology 2012, 56, 972–981.

- Bridgewater, J.; Galle, P.R.; Khan, S.A.; Llovet, J.M.; Park, J.W.; Patel, T.; Pawlik, T.M.; Gores, G.J. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2014, 60, 1268–1289.

- Hong, J.C.; Jones, C.M.; Duffy, J.P.; Petrowsky, H.; Farmer, D.G.; French, S.; Finn, R.; Durazo, F.A.; Saab, S.; Tong, M.J.; et al. Comparative analysis of resection and liver transplantation for intrahepatic and hilar cholangiocarcinoma: A 24-year experience in a single center. Arch. Surg. 2011, 146, 683–689.

- Mansour, J.C.; Aloia, T.A.; Crane, C.H.; Heimbach, J.K.; Nagino, M.; Vauthey, J.N. Hilar cholangiocarcinoma: Expert consensus statement. HPB 2015, 17, 691–699.

- Song, S.C.; Choi, D.W.; Kow, A.W.; Choi, S.H.; Heo, J.S.; Kim, W.S.; Kim, M.J. Surgical outcomes of 230 resected hilar cholangiocarcinoma in a single centre. ANZ J. Surg. 2013, 83, 268–274.

More