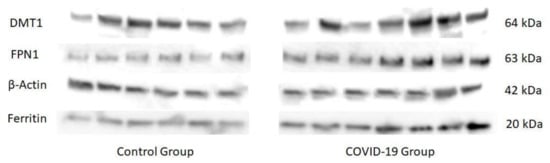

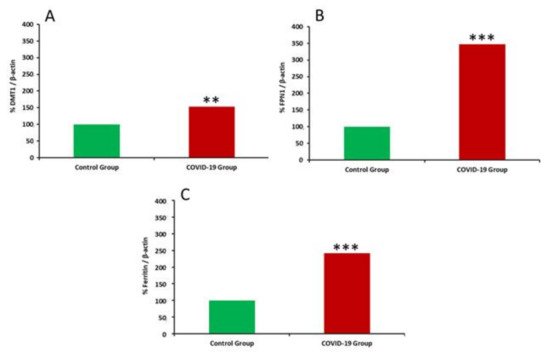

COVID-19, has the disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 has reached pandemic proportions worldwide, with considerable consequences for both health and the economy. In pregnant women, COVID-19 can alter the metabolic environment, iron metabolism, and oxygen supply of trophoblastic cells, and therefore have a negative influence on essentialpregnant women and mechanisms of fetal development, with implications in the postnatal life. The purpose of this study was to investigate, for the first time, the effects of COVID-19 infection during pregnancy with regard to the oxidative/antioxidant status in mothers’ serum and placenta, together with placental iron metabolism. Results showed no differences in superoxide dismutase activity and placental antioxidant capacity. However, antioxidant capacity decreased in the serum of infected mothers. Catalase activity decreased in the COVID-19 group, while an increase in 8-hydroxy-2’-deoxyguanosine, hydroperoxides, 15-FT-isoprostanes, and carbonyl groups were recorded in this group. Placental vitamin D, E, and Coenzyme-Q10 also showed to be increased in the COVID-19 group. As for iron-related proteins, an up-regulation of placental DMT1, ferroportin-1, and ferritin expression was recorded in infected women. Due to the potential role of iron metabolism and oxidative stress in placental function and complications, further research is needed to explain the pathogenic mechanism of COVID-19 that may affect pregnancy, so as to assess the short-term and long-term outcomes in mothers’ and infants’ health.

- COVID-19

- placenta

- pregnancy

- antioxidant system

- oxidative stress

- iron metabolism

1. Introduction

2. Results

Table 1 shows the clinical characteristics (including the haematological and biochemical parameters measured in the hospital) of the mothers participating in this study. No statistically significant differences were observed between groups for age, weight, height, BMI, parity, or delivery method. In the biochemical parameters shown, differences were only found in serum Fe concentrations with lower values in the COVID-19 group compared to the control group (p < 0.01).| Control | COVID-19 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) |

| Placenta | Serum | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | COVID-19 | Control | COVID-19 | ||

| 31.58 ± 1.09 | 31.96 ± 0.78 | ||||

| ± 9.28 | |||||

| ABTS (mmol/L Trolox) | 3.09 ± 0.15 | ||||

| 168.72 × 10 | |||||

| 3 | |||||

| 58.7 | |||||

| 3.11 ± 0.11 | 3.34 ± 0.175 | 2.78 ± 0.161 * | Weight (kg) ± 5.10 ** | 77.01 ± 5.90 | 62.86 ± 2.86 * |

| 8-OhdG (ng/mL) | |||||

| Control | COVID-19 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placenta (µg/mg protein) |

Vitamin D | 12.45 ± 0.58 | 14.06 ± 0.51 ** | |||

| 73.69 ± 2.55 | 74.12 ± 2.67 | |||||

| SOD (mU/mg protein) | 440.02 ± 40.14 | 430.25 ± 30.69 | 4.45 ± 0.43 | 3.92 ± 0.29 | Length (cm) | |

| Vitamin E | 64.80 ± 6.87 | 93.47 ± 7.27 ** | 166.83 ± 1.03 | 163.97 ± 0.68 | ||

| Coenzyme Q10 | 82.09 ± 4.06 | BMI (kg/m2) | 26.31 ± 1 | 27.3 ± 0.8 | ||

| A (%): 21.8 | ||||||

| CAT (mU/mg protein) | 186.18 × 103 | 92.13 ± 2.84 * | 283.70 ± 7.98 | 316.12 ± 6.95 ** | 75.82 ± 2.85 | Parity |

| Serum | Uni (%): 52.22 | 53.14 | ||||

| Multi (%): 47.28 | 46.86 | |||||

| 0.44 ± 0.02 | 0.48 ± 0.03 | Delivery method | V (%): 56.2 | |||

| Vitamin A | 2.29 ± 0.20 | 2.72 ± 0.28 | 19.9 | |||

| Control | COVID-19 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mn (µg/g DM) | 3.93 ± 0.92 | 7.47 ± 1.07 ** | ||||||

| Se (µg/g DM) | 7.47 ± 0.63 | 7.40 ± 0.64 | ||||||

| Ba (µg/g DM) | 0.47 ± 0.07 | 0.36 ± 0.03 | ||||||

| 82.38 ± 1.51 ** | ||||||||

| (µmol/L) | Vitamin D | 46.35 ± 2.59 | 53.22 ± 3.00 | Hydroperoxides (µM) | 40.73 ± 2.47 | 48.02 ± 1.90 *** | 1.51± 0.27 | 1.12 ± 0.20 |

| Vitamin E | 23.10 ± 2.35 | 29.47 ± 1.59 * | Isoprostanes (ng/mL) | 35.30 ± 1.31 | 39.85 ± 0.57 ** | 4.35 ± 0.87 | 8.85 ± 0.22 ** | |

| Carbonyl groups (nmol/mg protein) |

12.74 ± 0.67 | 16.37 ± 0.84 *** | 1.385 ± 0.026 | 1.601 ± 0.054 * | ||||

| C (%): 21.8 | 23.8 | |||||||

| Hemoglobin 2nd T (g/L) |

11.88 ± 0.23 | 11.53 ± 0.13 | ||||||

| Hemoglobin 3rd T (g/L) |

11.96 ± 0.23 | 11.72 ± 0.17 | ||||||

| Hematocrit 2nd T (%) |

35.32 ± 0.61 | 34.11 ± 0.37 | ||||||

| Hematocrit 3rd T (%) |

35.70 ± 0.63 | 34.82 ± 0.47 | ||||||

| Serum Iron 3rd T (µg/dL) |

97.05 ± 14.35 | 60.14 ± 9.87 ** |

| Cu (µg/g DM) | ||

| 8.66 ± 0.57 | 8.72 ± 0.38 | |

| Coenzyme Q10 | ||

| Zn (µg/g DM) | 49.18 ± 2.18 | 49.62 ± 1.51 |

| Fe (mg/g DM) | 3.54 ± 0.40 | 5.39 ± 0.45 ** |

References

- Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fan, G.; Xu, J.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020, 395, 497–506.

- Madinger, N.E.; Greenspoon, J.S.; Ellrodt, A.G. Pneumonia during pregnancy: Has modern technology improved maternal and fetal outcome? Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1989, 161, 657–662.

- Jamieson, D.J.; Honein, M.A.; Rasmussen, S.A.; Williams, J.L.; Swerdlow, D.L.; Biggerstaff, M.S.; Lindstrom, S.; Louie, J.K.; Christ, C.M.; Bohm, S.R.; et al. H1N1 2009 influenza virus infection during pregnancy in the USA. Lancet 2009, 374, 451–458.

- Benedetti, T.J.; Valle, R.; Ledger, W.J. Antepartum pneumonia in pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1982, 144, 413–417.

- Yu, N.; Li, W.; Kang, Q.; Xiong, Z.; Wang, S.; Lin, X.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, J.; Liu, H.; Deng, D.; et al. Clinical features and obstetric and neonatal outcomes of pregnant patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: A retrospective, single-centre, descriptive study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 559–564.

- Di Toro, F.; Gjoka, M.; Di Lorenzo, G.; De Santo, D.; De Seta, F.; Maso, G.; Risso, F.M.; Romano, F.; Wiesenfeld, U.; Levi-D’Ancona, R.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 on maternal and neonatal outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2021, 27, 36–46.

- Liu, H.; Wang, L.-L.; Zhao, S.-J.; Kwak-Kim, J.; Mor, G.; Liao, A.-H. Why are pregnant women susceptible to COVID-19? An immunological viewpoint. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2020, 139, 103122.

- Kagan, V.E.; Tyurina, Y.Y.; Bayir, H.; Chu, C.T.; Kapralov, A.A.; Vlasova, I.I.; Belikova, N.A.; Tyurin, V.A.; Amoscato, A.; Epperly, M.; et al. The “pro-apoptotic genies” get out of mitochondria: Oxidative lipidomics and redox activity of cytochrome c/cardiolipin complexes. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2006, 163, 15–28.

- Khairallah, R.J.; Kim, J.; O’Shea, K.M.; O’Connell, K.A.; Brown, B.H.; Galvão, T.; Daneault, C.; Rosiers, C.D.; Polster, B.; Hoppel, C.L.; et al. Improved Mitochondrial Function with Diet-Induced Increase in Either Docosahexaenoic Acid or Arachidonic Acid in Membrane Phospholipids. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34402.

- Díaz-Castro, J.; Pulido-Moran, M.; Moreno-Fernandez, J.; Kajarabille, N.; De Paco, C.; Garrido-Sanchez, M.; Prados, S.; Ochoa, J. Gender specific differences in oxidative stress and inflammatory signaling in healthy term neonates and their mothers. Pediatr. Res. 2016, 80, 595–601.

- Means, R.T. Iron Deficiency and Iron Deficiency Anemia: Implications and Impact in Pregnancy, Fetal Development, and Early Childhood Parameters. Nutrients 2020, 12, 447.

- Hirschhorn, T.; Stockwell, B.R. The development of the concept of ferroptosis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2019, 133, 130–143.

- Cavezzi, A.; Troiani, E.; Corrao, S. COVID-19: Hemoglobin, Iron, and Hypoxia beyond Inflammation. A Narrative Review. Clin. Pract. 2020, 10, 24–30.

- Frost, J.N.; Tan, T.K.; Abbas, M.; Wideman, S.K.; Bonadonna, M.; Stoffel, N.U.; Wray, K.; Kronsteiner, B.; Smits, G.; Campagna, D.R.; et al. Hepcidin-Mediated Hypoferremia Disrupts Immune Responses to Vaccination and Infection. Med 2020, 2, 164–179.e12.

- Lorena, D.; Isabella, N.; Daniele, V.; Giovanni Battista, V.; Andrea, M.; Andrea, V.; Patrizio, C.; Giovanna, G.; Filippo, B. COVID-19, inflammatory response, iron homeostasis and toxicity: A prospective cohort study in the Emergency Department of Piacenza (Italy). Res. Sq. 2022.

- Mirbeyk, M.; Saghazadeh, A.; Rezaei, N. A systematic review of pregnant women with COVID-19 and their neonates. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2021, 304, 5–38.

- Capobianco, G.; Saderi, L.; Aliberti, S.; Mondoni, M.; Piana, A.; Dessole, F.; Dessole, M.; Cherchi, P.L.; Dessole, S.; Sotgiu, G. COVID-19 in pregnant women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2020, 252, 543–558.