Fungi can synthesize a wealth of secondary metabolites, which are widely used in the exploration of lead compounds of pharmaceutical or agricultural importance. Beauveria, Metarhizium, and Cordyceps are the most extensively studied fungi in which a large number of biologically active metabolites have been identified. However, relatively little attention has been paid to Purpureocillium lilacinum. P. lilacinum are soil-habituated fungi that are widely distributed in nature and are very important biocontrol fungi in agriculture, providing good biological control of plant parasitic nematodes and having a significant effect on Aphidoidea, Tetranychus cinnbarinus, and Aleyrodidae. At the same time, it produces secondary metabolites with various biological activities such as anticancer, antimicrobial, and insecticidal.

- entomogenous fungi

- biosynthesis

- biocontrol

- nematodes

1. Introduction

2. Biosynthesis of Secondary Metabolites in Purpureocillium lilacinum

3. Problems and Perspectives

References

- Luangsa-Ard, J.; Houbraken, J.; van Doorn, T.; Hong, S.B.; Borman, A.M.; Hywel-Jones, N.L.; Samson, R.A. Purpureocillium, a new genus for the medically important Paecilomyces lilacinus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2011, 321, 141–149.

- Sampson, R.A. Paecilomyces and Some Allied Hyphomycetes. Cent. Voor Schimmelcultures 1975, 64, 174.

- Srilakshmi, A.; Sai Gopal, D.V.R.; Narasimha, G. Impact of bioprocess parameters on cellulase production by Purpureocillium lilacinum isolated from forest soil. Int. J. Pharma Bio Sci. 2017, 8, 157–165.

- Zhu, Y.; Ai, D.; Zhang, W. Difference of soil microbiota in perennial ryegrass turf before and after turning green using high-throughput sequencing technology. Res. J. BioTechnol. 2017, 12, 50–60.

- Redou, V.; Navarri, M.; Meslet-Cladiere, L.; Barbier, G.; Burgaud, G. Species richness and adaptation of marine fungi from deep-subseafloor sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 3571–3583.

- Liu, L.; Zhang, C.; Fan, H.; Guo, Z.; Yang, H.; Chen, M.; Han, J.; Cao, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhang, K.; et al. An efficient gene disruption system for the nematophagous fungus Purpureocillium lavendulum. Fungal. Biol. 2019, 123, 274–282.

- Silva, S.D.; Carneiro, R.M.D.G.; Faria, M.; Souza, D.A.; Monnerat, R.G.; Lopes, R.B. Evaluation of Pochonia chlamydosporia and Purpureocillium lilacinum for suppression of Meloidogyne enterolobii on tomato and banana. J. Nematol. 2017, 49, 77–85.

- Gine, A.; Sorribas, F.J. Effect of plant resistance and BioAct WG (Purpureocillium lilacinum strain 251) on Meloidogyne incognita in a tomato-cucumber rotation in a greenhouse. Pest Manag. Sci. 2017, 73, 880–887.

- Cavello, I.A.; Hours, R.A.; Rojas, N.L.; Cavalitto, S.F. Purification and characterization of a keratinolytic serine protease from Purpureocillium lilacinum LPS # 876. Process. Biochem. 2013, 48, 972–978.

- Desaeger, J.A.; Watson, T.T. Evaluation of new chemical and biological nematicides for managing Meloidogyne javanica in tomato production and associated double-crops in Florida. Pest Manag. Sci. 2019, 75, 3363–3370.

- Jiao, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Cao, H.; Mao, Z.; Ling, J.; Yang, Y.; Xie, B. Functional genetic analysis of the leucinostatin biosynthesis transcription regulator lcsL in Purpureocillium lilacinum using CRISPR-Cas9 technology. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 6187–6194.

- Wang, M.; Zhou, H.; Fu, Y.; Wang, C. The Antifungal Activities of the Fungus 36–1 to Several Plant Pathogens. Chin. J. Biol. Control. 1996, 12, 20–23.

- Li, F.; Chen, J.; Shi, H.; Liu, B. Anatgoinstic effect of biocontrol fungus, Paecilomyces lilacinus strain NH-PL-3 and its mechainsm against Fusairum oxyspourm. J. Plant Prot. 2005, 32, 373–378.

- Hotaka, D.; Amnuaykanjanasin, A.; Maketon, C.; Siritutsoontorn, S.; Maketon, M. Efficacy of Purpureocillium lilacinum CKPL-053 in controlling Thrips palmi (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) in orchid farms in Thailand. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 2015, 50, 317–329.

- Yoder, J.A.; Fisher, K.A.; Dobrotka, C.J. A report on Purpureocillium lilacinum found naturally infecting the predatory mite, Balaustium murorum (Parasitengona: Erythraeidae). Int. J. Acarol. 2018, 44, 139–145.

- Deng, J.X.; Paul, N.C.; Sang, H.K.; Lee, J.H.; Hwang, Y.S.; Yu, S.H. First Report on Isolation of Penicillium adametzioides and Purpureocillium lilacinum from Decayed Fruit of Cheongsoo Grapes in Korea. Mycobiology 2012, 40, 66–70.

- Guo, L.-N.; Wang, H.; Hsueh, P.-R.; Meis, J.F.; Chen, H.; Xu, Y.-C. Endophthalmitis caused by Purpureocillium lilacinum. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2019, 52, 170–171.

- Wang, G.; Liu, Z.; Lin, R.; Li, E.; Mao, Z.; Ling, J.; Yang, Y.; Yin, W.-B.; Xie, B. Biosynthesis of antibiotic leucinostatins in bio-control fungus Purpureocillium lilacinum and their inhibition on Phytophthora revealed by genome mining. PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1005685.

- Bode, H.B.; Bethe, B.; Hofs, R.; Zeeck, A. Big effects from small changes: Possible ways to explore nature’s chemical diversity. Chembiochem 2002, 3, 619–627.

- Liu, L.; Zhang, J.; Chen, C.; Teng, J.; Wang, C.; Luo, D. Structure and biosynthesis of fumosorinone, a new protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B inhibitor firstly isolated from the entomogenous fungus Isaria fumosorosea. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2015, 81, 191–200.

- Yurchenko, A.N.; Girich, E.V.; Yurchenko, E.A. Metabolites of Marine Sediment-Derived Fungi: Actual Trends of Biological Activity Studies. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 88.

- Li, X.-Q.; Xu, K.; Liu, X.-M.; Zhang, P. A Systematic Review on Secondary Metabolites of Paecilomyces Species: Chemical Diversity and Biological Activity. Planta Medica 2020, 86, 805–821.

- Wen, L.; Lin, Y.C.; She, Z.G.; Du, D.S.; Chan, W.L.; Zheng, Z.H. Paeciloxanthone, a new cytotoxic xanthone from the marine mangrove fungus Paecilomyces sp. (Tree1–7). J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2008, 10, 133–137.

- Prasad, P.; Varshney, D.; Adholeya, A. Whole genome annotation and comparative genomic analyses of bio-control fungus Purpureocillium lilacinum. BMC Genom. 2015, 16, 1004.

- Khaldi, N.; Seifuddin, F.T.; Turner, G.; Haft, D.; Nierman, W.C.; Wolfe, K.H.; Fedorova, N.D. SMURF: Genomic mapping of fungal secondary metabolite clusters. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2010, 47, 736–741.

- Weber, T.; Blin, K.; Duddela, S.; Krug, D.; Kim, H.U.; Bruccoleri, R.; Lee, S.Y.; Fischbach, M.A.; Muller, R.; Wohlleben, W.; et al. antiSMASH 3.0-a comprehensive resource for the genome mining of biosynthetic gene clusters. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, W237–W243.

- Takeda, K.; Kemmoku, K.; Satoh, Y.; Ogasawara, Y.; Shinya, K.; Dairi, T.J.A.C.B. N-Phenylacetylation and Nonribosomal Peptide Synthetases with Substrate Promiscuity for Biosynthesis of Heptapeptide Variants, JBIR-78 and JBIR-95. ACS Chem. Biol. 2017, 12, 1813.

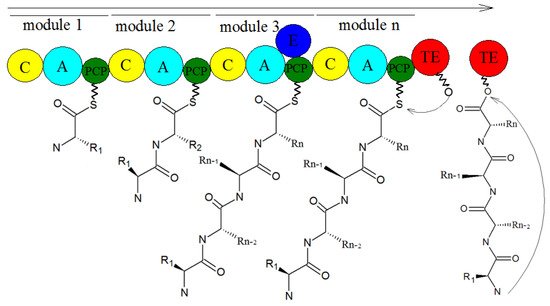

- Han, M.; Chen, J.; Qiao, Y.; Zhu, P. Advances in the nonribosomal peptide synthetases. Yaoxue Xuebao 2018, 53, 1080–1089.

- Sung, C.T.; Chang, S.; Entwistle, R.; Ahn, G.; Lin, T.; Petrova, V.; Yeh, H.; Praseuth, M.B.; Chiang, Y.; Oakley, B.R.; et al. Overexpression of a three-gene conidial pigment biosynthetic pathway in Aspergillus nidulans reveals the first NRPS known to acetylate tryptophan. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2017, 101, 1–6.

- Payne, J.A.E.; Schoppet, M.; Hansen, M.H.; Cryle, M.J. Diversity of nature’s assembly lines—recent discoveries in non-ribosomal peptide synthesis. Mol. Biosyst. 2017, 13, 9–22.

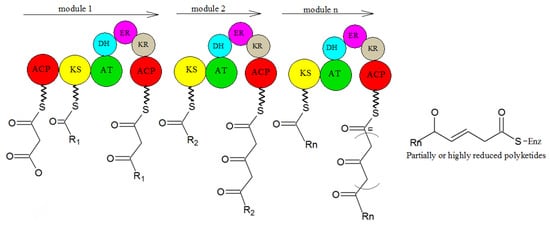

- Sun, Y.-H.; Deng, Z.-X. Polyketides and combinatorial biosynthetic approaches. Zhongguo Kangshengsu Zazhi 2006, 31, 6.

- Bloudoff, K.; Fage, C.D.; Marahiel, M.A.; Schmeing, T.M. Structural and mutational analysis of the nonribosomal peptide synthetase heterocyclization domain provides insight into catalysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 95–100.

- Strieker, M.; Tanovic, A.; Marahiel, M.A. Nonribosomal peptide synthetases: Structures and dynamics. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2010, 20, 234–240.

- Hertweck, C. The Biosynthetic Logic of Polyketide Diversity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 4688–4716.

- Schaeberle, T.F. Biosynthesis of alpha-pyrones. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2016, 12, 571–588.

- Sun, J.; Bu, J.; Cui, G.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, H.; Mao, Y.; Zeng, W.; Guo, J.; Huang, L. Accumulation and biosynthetic of curcuminoids and terpenoids in turmeric rhizome in different development periods. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi 2019, 44, 927–934.

- Hocquette, A.; Grondin, M.; Bertout, S.; Mallié, M. Les champignons des genres Acremonium, Beauveria, Chrysosporium, Fusarium, Onychocola, Paecilomyces, Penicillium, Scedosporium et Scopulariopsis responsables de hyalohyphomycoses. J. De Mycol. Médicale 2005, 15, 136–149.

- Okhravi, N.; Lightman, S. Clinical manifestations, treatment and outcome of Paecilomyces lilacinus infections. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2007, 13, 554.

- Weng, Q.; Zhang, X.; Chen, W.; Hu, Q. Secondary Metabolites and the Risks of Isaria fumosorosea and Isaria farinosa. Molecules 2019, 24, 664.