Sudden death is a rare event in the pediatric population but with a social shock due to its presentation as the first symptom in previously healthy children. Comprehensive autopsy in pediatric cases identify an inconclusive cause in 40–50% of cases. In such cases, a diagnosis of sudden arrhythmic death syndrome is suggested as the main potential cause of death. Molecular autopsy identifies nearly 30% of cases under 16 years of age carrying a pathogenic/potentially pathogenic alteration in genes associated with any inherited arrhythmogenic disease. In the last few years, despite the increasing rate of post-mortem genetic diagnosis, many families still remain without a conclusive genetic cause of the unexpected death.

- Brugada syndrome

- catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia

- channelopathies

- long QT syndrome

- short QT syndrome

1. Introduction

2. Inherited Arrhythmia Syndromes

3. Long QT Syndrome

3.1. Genetics

| Cardiac Phenotype | Inheritance Model | Frequency | Gene Curation |

Genes | Main Type of Mutations |

Current Affected |

Non-Cardiac Phenotype |

Phenotypic Overlap (Both LOF/GOF Variants) |

Ref. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LQTS | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| LQT1 | AD | 30–35% | Definitive genes | KCNQ1 | LOF | IKs | SNHL (AR), seizures |

JLNS (AR), SQTS, AF | [10][33][34][35][36][37][38] | [10,33,34,35,36,37,38] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| LQT2 | AD | 25–30% | KCNH2 | LOF | IKr | Seizures | SQTS, BrS, AF | [10][33][34][39] | [10,33,34,39] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| LQT3 | AD | 5–10% | SCN5A | GOF | INa | Multiple (including seizures) |

BrS, SQTS, CPVT, ERS, AF, AFL, ARVC/D, HCM, DCM, LVNC, SVT, AVB, SND, PCCD, WPW | [10] | 10 | [33][34][ | ,33 | 40 | ,34 | ] | ,40 | [41] | ,41 | [42] | [,42] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| LQT14–16 | AD | <1% | Definitive genes with atypical characteristics | CALM1–3 | GOF | ICa | Seizures, DD | CPVT | [10][33][43][44][45] | [10,33,43,44,45] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| LQT17 (TKOS) | AR | <1% | TRDN | LOF | ICa | Muscle weakness | CPVT | [10][33][46][47] | [10,33,46,47] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| LQT5 | AD | <1% | Genes with moderate or limited evidence, associated with multiorgan syndromes |

KCNE1 | LOF | IKs | SNHL (AR) | JLNS (AR) | [10][33][34][48] | [10,33,34,48] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| LQT8 | AD | <1% | CACNA1C | GOF | ICa | Dysmorphic and neurodevelopmental features | TS, SQTS, BrS, ERS, HCM, AF, SND, CND | [10][33][49][50][51][52][53] | [10,33,49,50,51,52,53] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| LQT7 | AD | <1% | KCNJ2 | LOF | IK1 | Muscle weakness, dysmorphic features, DD, seizures |

ATS, SQTS, AF, CPVT, DCM |

[10][33] | ,33 | [37] | ,37 | [42] | ,42 | [54] | ,54 | [55] | ,55 | [56][57][58] | [10,56,57,58] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| LQTS | AD | <1% each | Other genes with limited evidence | ANK2 | KCNJ5 | KCNE2 | AKAP9 | SCN4B | CAV3 | SNTA1 | LOF LOF LOF LOF GOF GOF GOF |

Many IK- | Ach | IKr IKs INa INa INa |

Seizures | CPVT, BrS, CND AF, SND AF |

[10][33][34][42][48][59][60][61][62][63] | [10,33,34,42,48,59,60,61,62,63] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| BrS | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| BrS1 | AD | 20–30% | Definitive gene | SCN5A | LOF | INa | Multiple (including seizures) |

BrS, SQTS, CPVT, ERS, AF, AFL, ARVC, HCM, DCM, LVNC, SVT, AVB, SND, PCCD, WPW | [12][64] | 64 | [65][66][67][68][69][70][71][72][73][74] | ,65 | [ | ,66 | 75 | ,67 | ][ | ,68 | 76] | [12,,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| BrS | AD | <5% | Genes with moderate or limited evidence |

ABCC9 | ANK2 | KCNH2 | KCNJ8 | KCND3 | KCNE3 | CACNA1C | CACNB2 | CACNA2D1 | HCN4 | PKP2 | GPD1-L | TRPM4 | SCN1B–3B SCN10A | SLMAP RANGRF | GOF GOF GOF GOF GOF GOF LOF LOF LOF LOF LOF LOF LOF LOF LOF LOF LOF |

IK- | ATP | Many IKr IK- | ATP | Ito Ito ICa ICa ICa Ih INa INa INa INa INa INa INa |

Seizures Seizures Seizures, SCA (See LQT8) |

ERS, AF, DCM LQTS, CPVT, CND LQTS, SQTS, AF ERS, AF ERS, AF, CND AF Multiple (see LQT8) SQTS, ERS, CND SQTS, ERS, CND AF, SND ARVC, DCM, ACM, CPVT DM LQTS AF AF |

[12][33][37][80][81] | [12,33,37 | [64] | ,64 | [77] | ,77 | [78] | ,78 | [79] | ,79,80,81] | ||||||||||||||

| XD | KCNE5 | LOF | Ito | AF | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CPVT | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CPVT1 | AD | 55–60% | Definitive genes | RYR2 | GOF | ICa | LQTS, HCM, LVNC, CRDS | [11][48][82][83][84][85][86][87] | [11,48,82,83,84,85,86,87] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CPVT2 | AR | 3–5% | CASQ2 | LOF | ICa | [11][48][88] | [11,48,88] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CPVT3 | AR | 1–2% | TECRL | LOF | ICa | [11]] | [11 | [48] | ,48 | [89][90 | ,89,90] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CPVT4 | AD | <1% | CALM1–3 | LOF | ICa | Seizures, DD | LQTS | [11][43][44][45][48] | [11,43,44,45,48] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CPVT5 | AR | 1–2% | TRDN | LOF | ICa | Muscle weakness | LQTS | [11][47][48][91] | [11,47,48,91] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CPVT | AD | <1% | Genes with moderate or limited evidence |

SCN5A | PKP2 | ANK2 | KCNJ2 | LOF LOF LOF LOF |

INa INa Many IK1 |

Multiple Seizures Seizures (See LQT7) |

Multiple (see BrS1) ARVC, DCM, ACM, CPVT LQTS, BrS, CND Multiple (see LQT7) |

[11][48][92] | [11,48,92] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SQTS | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SQT1 | AD | 15% | Definitive gene | KCNH2 | GOF | IKr | Seizures | LQTS, AF, BrS | [11][33][34][93] | [11,33,34,93] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SQT2–3 | AD | <5% each | Genes with strong-moderate evidence | KCNQ1 | KCNJ2 | GOF GOF |

IKs IK1 |

(See LQT1) (See LQT7) |

JLNS (AR), SQTS, AF Multiple (see LQT7) |

[10][11][33][34][35][36][37][38] | [10,11,33,34,35,36,37,38] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SQTS | AD | <1% | Gene with moderate evidence |

SLC4A3 | LOF | AE3 | [11][94] | [11,94] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SQTS | AD AR |

<1% each | Genes with limited evidence |

CACNA1C CACNB2 | CACNA2D1 | SCN5A SLC22A5 | LOF LOF LOF LOF LOF |

ICa ICa ICa INa INa |

(See LQT8) Multiple Metabolic decompensation, skeletal myopathy |

Multiple (see LQT8) SQTS, ERS, CND SQTS, ERS, CND Multiple (see BrS1) CDSP |

[11] | 11 | [33][65][ | ,33 | 95 | ,65 | ] | ,95 | [96] | ,96 | [97] | [,97] |

3.2. Definitive Genes for LQTS

3.3. Definitive Genes for LQTS with Atypical Characteristics

3.4. Genes with Moderate or Limited Evidence for LQTS

3.5. Genetic Modifiers and Acquired LQTS

3.6. Diagnosis

3.7. Risk Stratification

3.8. Genetic Counselling

3.9. Management and Treatment

4. Brugada Syndrome

4.1. Genetics

4.2. Definitive Gene for BrS

4.3. BrS2–12 and Other Susceptibility Genes with Limited Evidence

4.4. Diagnosis

4.5. Risk Stratification

4.6. Management and Treatment

4.7. Genetic Counseling

5. Short QT Syndrome

5.1. Genetics

5.2. SQT1 Definitive Gene: KCNH2

5.3. Genes with Strong or Moderate Evidence for SQTS

5.4. Diagnosis

5.5. Risk Stratification

5.6. Management and Treatment

5.7. Genetic Counselling

6. Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia

6.1. Genetics

6.2. Definitive Genes for CPVT

6.3. Diagnosis

6.4. Risk Stratification

6.5. Management and Treatment

6.6. Genetic Counseling

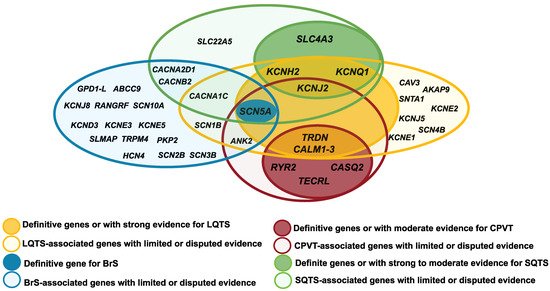

7. Genetic Overlap

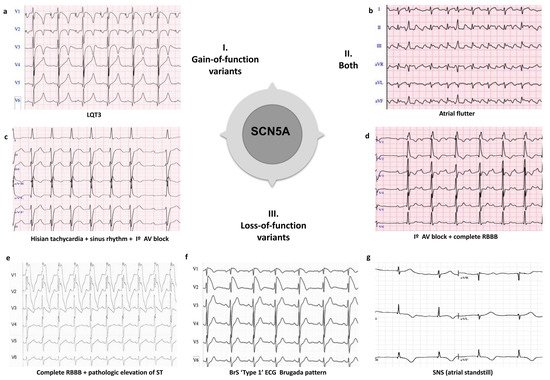

7.1. SCN5A Clinical Overlap