Heavy metal (HM) toxicity has become a global concern in recent years and is imposing a severe threat to the environment and human health. In the case of plants, a higher concentration of HMs, above a threshold, adversely affects cellular metabolism because of the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) which target the key biological molecules. Moreover, some of the HMs such as mercury and arsenic, among others, can directly alter the protein/enzyme activities by targeting their –SH group to further impede the cellular metabolism. Particularly, inhibition of photosynthesis has been reported under HM toxicity because HMs trigger the degradation of chlorophyll molecules by enhancing the chlorophyllase activity and by replacing the central Mg ion in the porphyrin ring which affects overall plant growth and yield. Consequently, plants utilize various strategies to mitigate the negative impact of HM toxicity by limiting the uptake of these HMs and their sequestration into the vacuoles with the help of various molecules including proteins such as phytochelatins, metallothionein, compatible solutes, and secondary metabolites.

1. Introduction

Feeding an exponentially growing population in the era of global climate change is a serious challenge. Among different environmental factors, abiotic stressors are the major factors affecting crop yield and the livelihood of mankind

[1]. In particular, heavy metal (HM) toxicity has emerged as one of the most serious threats to the crop production that might become even more prevalent in the coming decades. HMs are a group of 52 metals including lead (Pb), manganese (Mn), copper (Cu), nickel (Ni), cobalt (Co), cadmium (Cd), mercury (Hg), and arsenic (As) which directly affect the plant performance in a concentration-dependent manner

[2][3][2,3]. When present in adequate amounts, both micro and macronutrients maintain the functionality of key enzymes and regulate the metabolic pathways including photosynthesis, DNA synthesis, protein modifications, sugar metabolism, and redox homeostasis. However, at higher concentrations, these exhibit toxicities and can be lethal for all the lifeforms including plants as well as animals.

Increased anthropogenic activities such as mining, modern agriculture practicing, fertilizer application, extensive use of groundwater for irrigation, sewage disposal, and industrialization have disturbed the distribution of these HMs, leading to their accumulation at specific sites

[4][5][4,5]. Accumulation of HMs consequently affects soil health and texture because of the alteration in soil pH and the ratio of essential/or nonessential elements, which is a global concern for agricultural production

[6][7][6,7]. Moreover, absorption of these HMs from the contaminated soil and their accumulation, especially in food crops, are a serious concern for human health. It has been reported that these HMs, following their absorption from the contaminated soil, can accumulate in the edible plant parts and thus enter the food chain with a potential health risk to humans and animals

[8][9][8,9].

Plants growing in HM-contaminated soils show visible symptoms like stunted growth, chlorosis, root browning, and sometimes even death

[10][11][10,11]. Moreover, HM toxicity hinders the metabolic, cellular, and genetic potential of the plants required for normal growth and development. However, some of the plants can cope with a moderate concentration of HM(s) by reducing their uptake, their compartmentalization into vacuoles, their sequestration through phytochelatins (PC)/metallothioneins (MT), and activation of antioxidant defense

[12]. Since the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) is one of the most common effects of stress conditions in plants, activation of antioxidant defense mechanism is a major strategy to overcome the adverse effects of stress conditions. Nevertheless, the effectiveness and initiation of a particular defense response depend on the plant and type of HMs as well as their concentration and duration of exposure. Therefore, the need of the hour is to understand the effect of HM toxicity on crop plants in order to find a scientific way for improving crop yield in HMs contaminated soil, which is going to be more prevalent in near future.

2. Tolerance to HM Toxicity Is Mediated by a Complex Signaling Network

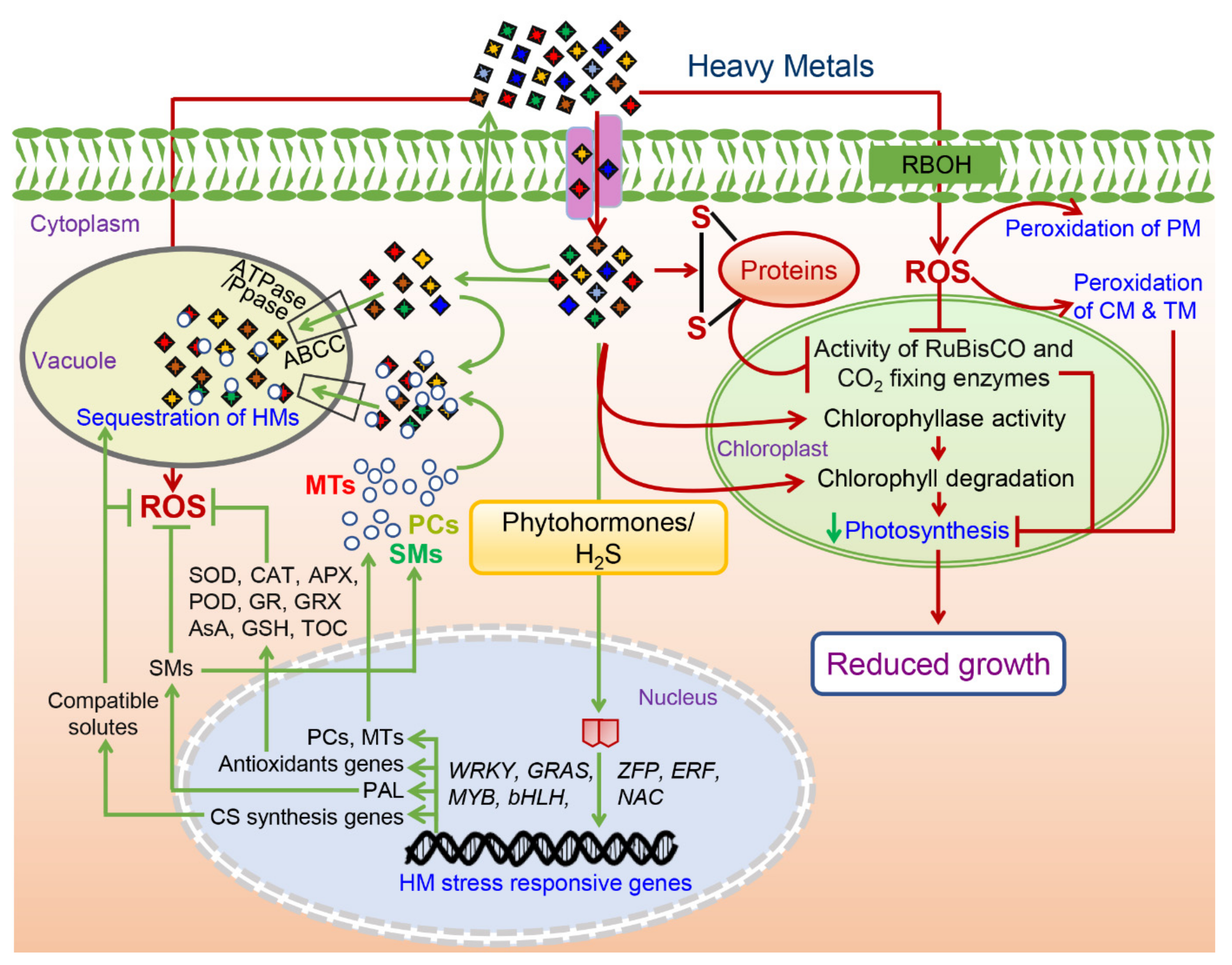

Plants under HM toxicity exhibit biochemical, physiological, and molecular changes as a part of their tolerance response, and understanding these responses is crucial to induce HM tolerance in sensitive crop plants (

Figure 13).

Figure 13. A graphical depiction highlighting interactions and crosstalk among phytohormones including abscisic acid (ABA), jasmonic acid (JA), salicylic acid (SA), brassinosteroids (BRs), polyamines (PA), ethylene, auxin, nitric oxide (NO), gibberellic acid (GA), and cytokinin (CK) under heavy metal exposure. HMs treatments increase endogenous levels of PA, BRs, SA, ABA, JA, ET, NO, and ROS amounts while the levels of auxin, GA, and CK were inhibited. The ROS produced in response to HM stress either by respiratory burst oxidase homolog (RBOH) activity and NADPH oxidase or by alteration in electron transport is also known to activate signal transduction. Alteration of these hormones and imbalance of ROS equilibrium leads to induction of antioxidant defense mechanism and HMs detoxification by promoting glutathione and phytochelatin biosynthesis, thus regulating HM stress tolerance to plants.

A growing body of evidence suggests a crucial role of various signaling molecules including H

2S and Cys in HM stress tolerance. Both H

2S and Cys are essential sulfur metabolism products that have emerged as novel gasotransmitters and redox signal molecules. At first, an upregulation of H

2S biosynthesis genes such as L-Cysteine desulfhydrase (

LCD) and L-Cysteine desulfhydrase 1

(DES1) was observed under Cd toxicity, suggesting a release of endogenous H

2S under HM-toxicity. Therefore, to confirm the roles of these two signaling molecules, mutants of H

2S (

lcddes1-1) and Cys (

oasa1, O-acetylserine(thiol)lyase isoform A1) biosynthesis genes were developed in Arabidopsis which were defective in the production of H

2S and Cys. Interestingly, these mutants showed decreased Cd stress tolerance as compared with the WT, which confirmed the pivotal roles of these two molecules in HM-stress tolerance

[13][128]. Similarly, Arabidopsis

oasa1-1 and

oasa1-2 mutants, which are defective in Cys production, showed significantly reduced Cd tolerance

[14][129]. Altogether, it has been proposed that H

2S and Cys participate in suppressing HM stress in plants via inhibiting ROS burst by inducing the expression level of MT genes, alternative respiration capacity, antioxidant activity, and GSH accumulation following the enhancement of the level of PCs genes (

Figure 2)

[13][128]. In addition to PCs, several other genes have been shown to play a positive role in mitigating HM toxicity (

Table 1).

Table 1. List of the genes expressed under toxicities of different HMs.

| Plant |

Gene(s) |

Metal(s) |

Reported Phenotypes |

References |

| Lemna turonifera |

AtNHX1 |

Cadmium |

vacuolar sequestration of metabolites and improved tolerance |

Yao et al., 2020 |

| Triticum aestivum L. |

TaCATs |

Arsenic |

Stress tolerance |

Tyagi et al., 2020 |

| Oryza sativa |

CCoAOMT |

Copper |

Lignin production and enhanced tolerance |

Su et al., 2020 |

| Oryza sativa |

cadA and bmtA |

Cadmium |

Cd accumulation and Cd-nanoparticles (CdNPs) biosynthesis and improved tolerance by decreasing oxidative stress |

Shi et al., 2020 |

| Hordeum vulagare |

HvPAL, HvMDH andHvCSY |

Copper and Cobalt |

Accumulation of phenolics and amino acids and increased tolerance |

Lwalaba et al., 2020 |

| Jatropha curcas |

JcMT2a andJcPAL |

Lead |

Accumulation of antioxidants, e.g., flavonoids and phenolics and metal detoxification |

Mohamed et al., 2020 |

| Tobacco |

EhMT1 |

Copper |

Decreased hydrogen peroxide (H | 2 | O | 2 | ) formation and increased tolerance |

Xia et al., 2012 |

| Tobacco |

TaMT3 |

Cadmium |

Increased superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity and conferred tolerance |

Zhou et al., 2014 |

| Tobacco |

OSMT1e-p |

Copper and Zinc |

ROS scavenging and enhanced tolerance |

Kumar et al., 2012 |

| Arabidopsis thaliana |

BjMT2 |

Copper and Cadmium |

Inhibits root elongation but increased tolerance |

Zhigang et al., 2006 |

| Hibiscus cannabinus L. |

WRKY, GRAS, MYB, bHLH, ZFP, ERF, and NAC |

Cadmium |

Enhanced tolerance via molecular mechanism |

Chen et al., 2020 |

| Tobacco |

NtCBP4 |

Lead |

Increased tolerance |

Sunkar et al., 2000 |

| Arabidopsis thaliana |

ACBP1 |

Lead |

Higher gene expression and enhanced tolerance |

Xiao et al., 2008; Du et al., 2015 |

| Linum usitatissimum L. |

LuACBP1 and LuACBP2 |

Lead |

Transcript level was higher in transgenic and improved tolerance |

Pan et al., 2020 |

| Oryza sativa |

OsSTAR1 and OsSTAR2 |

Aluminium |

Decreased aluminium level in cell wall and enhanced tolerance |

Huang et al., 2020 |

| Fragaria vesca |

FvABCC11 |

Cadmium |

Increased tolerance via ATP binding cassette (ABC) transporters |

Shi et al., 2020 |

| Arabidopsis thaliana |

AtABCC3 and AtABCC6 |

Cadmium |

Phytochelatin mediated tolerance during seedling development |

Brunetti et al., 2015; Gaillard et al., 2008 |

| Oryza sativa |

OsABCC1 |

Arsenic |

Increased tolerance via vacuolar sequestration |

Song et al., 2014 |

| Arabidopsis thaliana |

AtABCC1 and AtABCC2 |

Cadmium and Mercury |

Enhanced tolerance via vacuolar sequestration |

Park et al., 2012 |

| Brassica napus |

BnaABCC3 and BnaABCC4 |

Cadmium |

Enhanced stress tolerance |

Zhang et al., 2018 |

| Triticum aestivum |

TaABCC |

Cadmium |

Distinct molecular expression and increased tolerance |

Bhati et al., 2015 |

For instance, upregulation of acyl-CoA-binding proteins

ACBP1 and

ACBP4 was reported under Pb

2+ stress and the overexpression of

ACBP1 gene improved tolerance to Pb

2+ in Arabidopsis

[15][16][130,131]. Moreover, transgenic tobacco overexpressing a truncated

NtCBP4 was more tolerant to Pb

2+ as compared with plants overexpressing the full-length

NtCBP4 gene

[17][132]. Moreover, the disruption of the homologous Arabidopsis

CNGC1 gene (cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channel) conferred tolerance to Pb toxicity.

NtCBP4 and

AtCNGC1 are both components of a transport pathway that facilitates the entry of Pb

2+ into plant cells and thus disruption of these genes could be an important strategy for inducing the HM-stress tolerance in plants by limiting the uptake of these HMs inside the plant cells.

Transcription factors such as GRAS (GRAS domain family), myeloblastosis protein (

MYB),

C2H2, bHLH, NAC, basic leucine zipper (bZIP), ethylene-responsive (ERF), and

WRKY, among others, are emerging out to be the regulators of HM-stress tolerance in plants

[18][19][20][21][22][133,134,135,136,137]. For instance, transcriptome analysis of kenaf (

Hibiscus cannabinus L.) showed enhanced expression of various transcription factors, including

WRKY, GRAS, MYB, bHLH, ZFP, ERF, and

NAC under Cd stress

[22][137]. Similarly, activation of a large number of WRKY genes along with C2H2 zinc finger protein, AP2 domain-containing protein, MYB, and HSF have been reported in Arabidopsis under Pb and Cd toxicities

[23][24][138,139] and in rice under Cd-stress conditions

[18][19][133,134]. In Arabidopsis, several transcription factors including a Zinc-Finger protein ZAT6 were found to be induced during Cd stress and provided tolerance via the glutathione-dependent PC pathway

[25][140].

Figure 2. A putative diagram showing positive and positive molecular responses of the heavy metals (HM) toxicity in the plants. Responses marked with the red color represent negative effects of the HM toxicity while those marked with the green color represent tolerance response to alleviate the HM toxicity. Abbreviations: ROS—reactive oxygen species; SMs—secondary metabolites; CS—compatible solutes; PCs-phytochelatins; MTs—metallothioneins; SOD—superoxide dismutase; CAT—catalase; APX-ascorbate peroxidase; POD—peroxidase; GR—glutathione reductase; GRX—glutaredoxins; AsA—ascorbic acid; GSH—reduced glutathione; TOC—tocopherol; PAL—phenylalanine ammonia lyase; RBOH—respiratory burst oxidase homolog; PM—plasma membrane; CM—chloroplast membrane; TM—thylakoid membrane.

Figure 2. A putative diagram showing positive and positive molecular responses of the heavy metals (HM) toxicity in the plants. Responses marked with the red color represent negative effects of the HM toxicity while those marked with the green color represent tolerance response to alleviate the HM toxicity. Abbreviations: ROS—reactive oxygen species; SMs—secondary metabolites; CS—compatible solutes; PCs-phytochelatins; MTs—metallothioneins; SOD—superoxide dismutase; CAT—catalase; APX-ascorbate peroxidase; POD—peroxidase; GR—glutathione reductase; GRX—glutaredoxins; AsA—ascorbic acid; GSH—reduced glutathione; TOC—tocopherol; PAL—phenylalanine ammonia lyase; RBOH—respiratory burst oxidase homolog; PM—plasma membrane; CM—chloroplast membrane; TM—thylakoid membrane.

3. Sequestration and Compartmentalization: Plants’ Way to Alleviate the HM Toxicity

During their growth and development, plants absorb essential elements such as carbon (C), nitrogen (N), potassium (K), zinc (Zn) as well as non-essential elements such as Cd, Hg, and Pb, among several others

[26][141]. Although trace quantities of non-essential elements are beneficial for plant growth, excessive accumulation of these elements adversely affects various physiological and metabolic processes and deteriorates plant growth and development

[26][141]. Metal accumulation in plants is majorly governed by the two processes including their uptake inside the plant cells and their translocation from roots to other parts

[27][142]. In most of the cases, the major percentage of the HMs in plants is transported from root to stem and thus the concentration of HMs in the aboveground parts is higher than the roots; however, the most toxic HMs are commonly not transported in non-hyperaccumulating plants and the highest concentration is usually found in the roots

[28][79]. For instance, in tomato plants, the highest concentrations for Cu, Ni, Cr, Mn, and Pb were reported in order of root > leaf > stem > fruit

[29][143].

HM stress-tolerant and hyperaccumulator plants get rid of the unused and extra amount of metal ions by effluxing and/or compartmentalization majorly in the vacuole with the help of two vacuolar proton pumps, including an ATPase and a Ppas (

Figure 2)

[30][31][32][144,145,146]. For instance, sequestration of Zn in the hyperaccumulator plants has been majorly observed in the vacuoles of epidermal cells and trichomes of mesophyll cells, as shown in

Thlaspi caerulescens [33] [147] and in

Arabidopsis helleri respectively

[34][35][148,149]. In addition, Zn can also be accumulated, although to a lesser extent, in the cell wall and cytosol in leaves of another hyperaccumulator plant

P. griffithii [36][150]. Apart from the Zn, Ni was also found to be accumulated in the vacuoles of a Ni hyperaccumulator plant

Alyssum serpytllifolium [37][151]. Similar findings were also reported in the case of tolerant plants such as

B. juncea, Silene vulgaris [38][39][40][152,153,154], and

Brassica napus [35][41][149,155] where an accumulation of Cd has been reported majorly in the epidermal and mesophyll cells.

Apart from sequestration, plants minimize the HM toxicity by limiting the absorption of HMs from the soil through secretion of chelating compounds in the root hairs

[42][156]. Plants synthesize cystine-rich metal-binding peptides known as PCs and MTs to chelate the HMs. Among different HMs, Cd has been identified as the most potent inducer of PC synthesis in plants

[28][43][44][45][79,117,157,158]. These PCs bind to the HMs and sequester them into the vacuoles; however, PCs accumulation does not always have a beneficial effect on plants. For instance, rice plants expressing

TaPCS1 from

Triticum aestivum were found to be Cd sensitive and showed enhanced Cd accumulation in shoots

[46][159]. Similar to the PCs, MTs also act as biochelators and can directly bind to various HMs such as Zn, Cu, Cd, and Ni, among others. These MTs are localized in the membrane of the Golgi apparatus and growing evidence also indicates their role in maintenance of ROS homeostasis during HM toxicity. For instance, ectopic expression of different MT genes including type 1, type 2, and type 3 genes from a variety of plants such as rice,

B. juncea, and

Elsholtzia haichowensis has been shown to enhance the tolerance to Cu and/or Cd stress in transgenic plants

[47][48][49][160,161,162]. This MT-induced enhanced HM-toxicity tolerance was because of the increased SOD

[50][163] and POD

[51][164] activities and decreased production of hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2) that protected the transgenic plants from the HM-toxicity-induced oxidative stress. Similar to the MTs, some of the beneficial elements such as silicon (Si) and selenium (Se) also participate in the HM-stress tolerance by limiting the uptake of HMs and enhancing the activities of antioxidant enzymes

[52][165]. There are now ample reports which have shown that the exogenous application of either of these two metals enhances plants’ tolerance to HM toxicity

[53][166]. For instance, exogenous treatment of Si has been shown to decrease the uptake, transport, and accumulation of Cd in various plants such as peanut,

Cucumis sativus, cotton, and

Brassica chinensis and mitigate the toxic effects of Cd toxicity by reducing the electrolyte leakage, MDA and H

2O

2 contents and improving the activities of antioxidant enzymes such as CAT, SOD, and POD

[54][55][56][57][167,168,169,170].

Apart from these proteins and metals, various secondary metabolites also act as metal chelators and are involved in the sequestration of HMs to vacuole to provide HM-stress tolerance (

Figure 2). Su et al. (2020) investigated the role of lignin in HM-stress tolerance and found that two lignin-defective mutants (

ldm1 and

ldm2) of rice showed dwarf shoots and roots due to higher levels of Cu accumulation in the roots and leaf sheaths tissues, suggesting that the promotion of lignin synthesis in plants may be an adaptive strategy for Cu adaptation

[58][171]. Interestingly, a higher accumulation of phenolics and amino acids was found to be associated with Co and Cu stress tolerance. It was observed that exposure of Co and/or Cu significantly reduced chlorophyll content and photosynthetic and transpiration rates of the two barley genotypes. In the comparison of a single treatment of Co or Cu, their co-application significantly attributed the higher accumulation of phenolics, including cinnamic acid and benzoic acid derivatives, together with free amino acids in tolerant genotypes (Yan66) than in susceptible genotype (Ea52). Moreover, phenolic compounds also participated in the vacuolar sequestration of Cd which enhanced Cd tolerance in

Thlaspi caerulescens [59][172]. In

Jatropha curcas, phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (

JcPAL) genes were identified in the metal detoxification mechanism along with the metallothioneins (

JcMT2a). Interestingly, the transcript levels of

JcPAL-R and

JcPAL-L were upregulated with increasing Pb dose in a dose-dependent manner. Overall, their results suggested that along with the steadiness of growth traits, upregulation of metal transporter, and antioxidant defense system and higher accumulation of antioxidants including flavonoids and phenolics also participate in alleviating the HM-toxicity

[60][173]. Similarly, the phenylalanine ammonium lyase-related gene (

HvPAL) was found to be highly upregulated along with the genes (

HvMDH and

HvCSY), involved in the biosynthesis of malate and citrate, under the combined treatment of Co and Cu in barley. Some organic acids such as citrate and malate are known to participate in HM tolerance directly or indirectly

[61][174]. The increase of these organic acids might be responsible for energy production under the combined treatment to fulfill the higher energy demand by metal transporters to improve Co and Cu tolerance

[62][175]. These metal transporters, including ABC type transporters, are a group of organic solute transporters that help in vacuolar sequestration of “PC-metal complexes” and play an important role in metal ion homeostasis and tolerance

[63][64][176,177]. For instance, it was shown that “PC-metal complexes” of metal ions such as Zn

2+, Cu

2+, and Mn

2+ can be transported into the vacuole through the putative ABC transporter(s)

[65][178]. A recent study has highlighted that H

2S functions by regulating the expression levels of genes of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) superfamily to provide HM-stress tolerance

[66][67][179,180]. In rice, H

2S was found to alleviate the Al

3+ toxicity by enhancing the expression levels of ABC transporters, including

OsSTAR1 and

OsSTAR2 genes which prevent entering of Al into the cytoplasm

[68][181]. Besides, some other studies have also highlighted the pivotal roles of ABC and other transporters in HM-stress tolerance. For instance, upregulation of wheat ABCC transporters including

TaABCC3, TaABCC4, TaABCC11, and

TaABCC14 was observed under Cd toxicity

[69][182]. In

Brassica napus, ABCC transporters

BnaABCC3 and

BnaABCC4 were upregulated under Cd stress and enhanced Cd tolerance by limiting the entry of Cd inside the cells and their phytochelatin-mediated detoxification

[70][183]. Similar observations have been observed in Arabidopsis where ABCC transporters

AtABCC3 and

AtABCC6 were found to be involved in phytochelatin-mediated Cd tolerance during seedling development

[71][72][184,185]. In addition to these expression studies, overexpression studies have further supported the role of ABC transporters in HM-stress tolerance. For instance, overexpression of

FvABCC11 gene increased Cd tolerance in strawberry

[73][186] and

AtABCC1 and

AtABCC2 conferred tolerance to Cd and Hg in Arabidopsis through the vacuolar sequestration of these HMs

[74][187]. It was determined that

OsABCC1 regulated As-stress tolerance by sequestering As in vacuoles of the phloem companion cells of the nodes in rice grains

[65][178]. Similarly, a heavy metal transporter gene

AtPDR8 (an ABC transporter) was identified as a cadmium-extrusion pump in Arabidopsis to mediate resistance against Cd and Pb toxicity

[75][188].

Along with the ABC transporters, involvement of other transporters including multidrug and toxic compound extrusion (MATE) family proteins

[76][77][189,190], zinc-iron permease (

ZIP), iron-regulated transporters (

IRT1)

[77][190], natural resistance-associated macrophage proteins (NRAMP), copper transporters (Ctr/COPT), and heavy metal ATPase (HMA) transporters

[78][191] has also been highlighted in tolerance to HM toxicity. These metal transporters are involved in mediating metal intake and translocation in plants

[79][192]. For instance, IRT1 (a Fe transporter gene) that belongs to the ZIP family has been identified in Arabidopsis that leads to high-affinity Fe uptake under Fe-deficient conditions

[80][193] along with uptake of other heavy metals such as Cd and Zn

[81][194]. Other ZIP metal transporters such as

ZIP1 and

ZIP2 were identified as Zn and Mn transporters in roots that mediate remobilization of Zn and/or Mn from the vacuole to root stele

[82][195].

Metal transporters such as cation diffusion facilitator (CDF) transporters, ferroportins, VIT1/CCC1 also play a crucial role in the detoxification of HMs in plants and prominently remove transition metals out of the cytoplasm in the plant cell

[83][196]. ZAT transporters (a CDF transporter) in Arabidopsis such as

ZAT1 showed a significant role in Zn metal sequestration as transgenic lines with overexpression of

ZAT1 exhibited increased Zn resistance

[84][197]. It was hypothesized that ZAT is involved in vesicular or vacuolar sequestration of HMs such as Zn and thus is involved in enhancing Zn tolerance in plants

[84][197]. The expression of

ZTP1 (a ZAT gene) in the Zn hyperaccumulators such as

Thlaspi caerulescens in response to calamine (source of Zn, Pb, and Cd) and serpentine (rich in Ni) suggests the alleviatory role of

ZTP1 in plants during HM toxicity

[84][85][197,198].

ShMTP1, a CDF transporter, confers Mn tolerance in Arabidopsis by sequestering metal to internal organelles and may function as an antiporter of Mn to enhance tolerance

[86][199]. Several P

1B-ATPases in Arabidopsis have been identified that majorly alleviate metal accumulation. For instance, ectopic overexpression of

AtHMA4 in Arabidopsis mediated plant growth and development by enhancing the root growth and root-to-shoot metal translocation in the presence of toxic heavy metals (Zn, Co, and Cd)

[87][200]. The expression of P-type ATPase transporters enhanced under Pb stress in

Brassica juncea plants

[88][201] and tomato seedlings

[89][202]. The metal transporters including ABC, ZIP, NRAMP, Ctr/COPT, and HMA maintain metal homeostasis via activating different signaling components such as MAPK signaling and hormone and calcium signaling

[90][203]. Metal tolerance proteins (MTP) are also considered to be the potential efflux transporters that extrude mainly Zn out of cytoplasm along with other metals (Mn, Fe, Cd, Co, and Ni)

[91][204].

MTP1 confers to Zn hypertolerance in plants during high Zn concentration

[92][205]. Identification of undiscovered transporter genes, their functional characterization, and their manipulation can further aid in the production of hyperaccumulators as well as plants with enhanced phytoremedial potential. The HM-stress detoxifying transporters can be employed in growing applications of molecular-genetic technologies for a better understanding of heavy metal accumulation and tolerance in plants. These transporters either limit the entry of HMs into the cells or are involved in the vacuole sequestration of these HMs to improve HM-stress tolerance.

4. Conclusions

Figure 2. A putative diagram showing positive and positive molecular responses of the heavy metals (HM) toxicity in the plants. Responses marked with the red color represent negative effects of the HM toxicity while those marked with the green color represent tolerance response to alleviate the HM toxicity. Abbreviations: ROS—reactive oxygen species; SMs—secondary metabolites; CS—compatible solutes; PCs-phytochelatins; MTs—metallothioneins; SOD—superoxide dismutase; CAT—catalase; APX-ascorbate peroxidase; POD—peroxidase; GR—glutathione reductase; GRX—glutaredoxins; AsA—ascorbic acid; GSH—reduced glutathione; TOC—tocopherol; PAL—phenylalanine ammonia lyase; RBOH—respiratory burst oxidase homolog; PM—plasma membrane; CM—chloroplast membrane; TM—thylakoid membrane.

3. Conclusions

HM toxicity is emerging as one of the most serious concerns across the globe. The toxic effects of HMs on plants depend on a variety of factors including type and concentration of HMs and plant species, plant growth stage, and exposure time. The negative effects of the HMs on the growth of the plants are the combined outcome of the changes in their anatomy and physiology. Tolerant plants retaliate to HM toxicity by activating a complex signaling network which often culminates into activation of a defense response that includes accumulation of (1) antioxidants for detoxification of excess ROS, (2) secondary metabolites for sequestration of HMs to vacuoles, and (3) compatible solutes for the osmoregulation along with regulation of metal transporters, among others. The information derived from the HM accumulator/hyperaccumulator plants can be used in the future to improve the ability of non-food plants to accumulate higher amounts of HMs in order to be used to mitigate the HM contamination in environmental matrices. Moreover, the information derived from the HM tolerant plants can be used to induce the mechanisms that result in reduced uptake and accumulation of HMs in food plants and thus their negative consequences for human health.

Figure 2. A putative diagram showing positive and positive molecular responses of the heavy metals (HM) toxicity in the plants. Responses marked with the red color represent negative effects of the HM toxicity while those marked with the green color represent tolerance response to alleviate the HM toxicity. Abbreviations: ROS—reactive oxygen species; SMs—secondary metabolites; CS—compatible solutes; PCs-phytochelatins; MTs—metallothioneins; SOD—superoxide dismutase; CAT—catalase; APX-ascorbate peroxidase; POD—peroxidase; GR—glutathione reductase; GRX—glutaredoxins; AsA—ascorbic acid; GSH—reduced glutathione; TOC—tocopherol; PAL—phenylalanine ammonia lyase; RBOH—respiratory burst oxidase homolog; PM—plasma membrane; CM—chloroplast membrane; TM—thylakoid membrane.

Figure 2. A putative diagram showing positive and positive molecular responses of the heavy metals (HM) toxicity in the plants. Responses marked with the red color represent negative effects of the HM toxicity while those marked with the green color represent tolerance response to alleviate the HM toxicity. Abbreviations: ROS—reactive oxygen species; SMs—secondary metabolites; CS—compatible solutes; PCs-phytochelatins; MTs—metallothioneins; SOD—superoxide dismutase; CAT—catalase; APX-ascorbate peroxidase; POD—peroxidase; GR—glutathione reductase; GRX—glutaredoxins; AsA—ascorbic acid; GSH—reduced glutathione; TOC—tocopherol; PAL—phenylalanine ammonia lyase; RBOH—respiratory burst oxidase homolog; PM—plasma membrane; CM—chloroplast membrane; TM—thylakoid membrane.