This paper provides a comprehensive review of the current literature about biological properties and available methods for the detection of beta-glucans. It shares the experience of the Nanotechnology Characterization Laboratory with the detection of beta-glucans in nanotechnology-based drug products. This is the only paper in the current literature that summarizes and discusses five different approaches currently applied for the data interpretation of beta-glucan tests with respect to the acceptability (or lack thereof) of the beta-glucan levels in pharmaceutical products.

- nanomaterials

- immunology,

- toxicology

- beta-glucan

- endotoxin

- preclinical

- immunogenicity

- innate immunity modulating impurities

- pyrogenicity

- inflammation

Note:All the information below can be edited by authors. And the entry will be online only after authors edit and submit it.

Definition:

Beta-glucans are a family of polysaccharides with heterogeneous chemical structures that are present in the cell walls of certain microorganisms (e.g., some bacteria, yeast, and fungi), algae, mushrooms and plants [14–17]. Several types of beta-glucan molecules have been described in the literature based on the positioning of the β-glycosidic bond(s)―β-(1,3); β-(1,3), β-(1,4); β-(1,3), β-(1,2), β-(1,4), β-(1,6); β-(1,2) and β-(1,3), β-(1,6)―connecting individual monomer units of d-glucose into a polymer [18]. The β-glucan polymers can take a variety of forms. Linear (short and long), branched (branch-on-branch and side-chain branched), and cyclic molecules of beta-glucans have all been identified, and can utilize a single glycosidic linkage (e.g., the linear β-(1,3)-d-glucan polymer) or multiple glycosidic linkages (e.g., the branched β-(1,3), β-(1,6)-d-glucan polymer). Alpha-glucans, which are polysaccharides of alpha-d-glucose rather than beta-d-glucose, are also commonly found in microorganisms and plants. However, α-glucans are much less pro-inflammatory as compared to β-glucans and at the moment are not considered a significant IIMI risk.

1. Introduction

Concerns about and methodologies for the detection of innate immunity modulating impurities (IIMIs) in pharmaceutical products have a long history [1]. The issue of potential product contamination with IIMIs received more attention when biopharmaceuticals (e.g., recombinant proteins, antibodies, and peptides) entered the generics phase [1,11]. The determination of bioequivalence for generic biotechnology products to their respective reference listed drugs (RLDs), among other tests, requires an understanding of the products’ immunogenicity, which in turn may be influenced by IIMIs. Therefore, accentuating the importance of detection of these impurities in drug products and understanding how their presence affects products’ safety profiles have become important issues for drug development [12,13].

2. Detection of Beta-Glucans

Unlike bacterial endotoxins, the levels of β-(1,3)-d-glucan contaminants in pharmaceutical products are currently not regulated. There is no compendial standard for their detection or harmonized approach to acceptable levels. Nevertheless, there is a growing trend in the industry and among regulatory authorities worldwide to detect and quantify β-(1,3)-d-glucans, and to understand their safe levels [32–34].

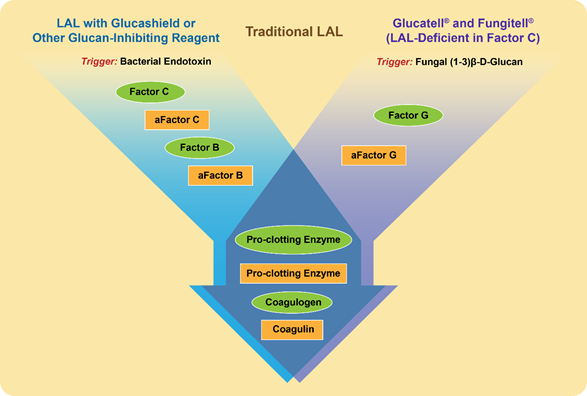

Similarly to endotoxin, beta-glucans activate a cascade of proteins present in the lysate derived from amoebocytes of the horseshoe crab Limulus polyphemus and widely used in the so-called Limulus amoebocyte lysate (LAL) assay [67] (Figure 1). The raw lysate obtained from amoebocytes contains two proteins that trigger the activation of the proteolytic cascade in response to endotoxin and beta-glucans; they are factor C and factor G, respectively [67]. When the LAL assay is conducted using this lysate, the presence of factor G creates a false-positive interference of beta-glucans during endotoxin detection [68]. To overcome such interference, the assay is either modified to include glucan-blocking reagents or performed using recombinant factor C [2,69,70]. Likewise, when factor C is depleted from the lysate, the remaining factor G initiates a proteolytic cascade in response to the presence of beta-glucans [71] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Proteins and triggering factors of the Limulus amoebocyte lysate (LAL) Assay. Proteins in the amoebocyte lysate of the horseshoe crab Limulus Polyphemus are zymogens organized in a sequential enzymatic cascade. These proteins are shown in the figure as green ovals. After the activation by either a triggering factor or preceding protein, the active form of a protein forms and is shown as a yellow rectangle; “a” at the beginning of the protein name refers to its activated state. The LAL assay can detect both endotoxins and beta-glucans. However, with slight modifications shown in the figure, the LAL may become specific to either endotoxin (left flow diagram shown in blue) or beta-glucan (right flow diagram shown in purple). These modifications are used in commercial kits (e.g., Fungitell and Glucatell) [48,72], and other commercially available reagents (e.g., Glucashield) [73].

While the LAL assay is widely used for the detection and quantification of endotoxin contamination, its factor-C-free version, available from various manufacturers and under different tradenames, including Fungitell, Glucatell, Endosafe Nexgen-PTS, and Toxinometer MT-6500, is used to detect beta-glucans (Table 1). The Glucatell assay is used for research purposes [72], whereas the Fungitell assay is approved by the US FDA for the diagnosis of fungal infections [48]. The Fungitell assay has also been available in Europe since 2008. Toxinometer MT-6500 is another diagnostic assay that is available in the US and Asia [74]. Additional methods have also been described; they include ELISA [75] and chemical hydrolysis and enzymatic degradation-based methods [76–78] (Table 1). Modified LAL and ELISA assays provide higher sensitivity and are used for the detection of beta-glucans in pharmaceuticals, and in the case of diagnostic assays, in patients’ sera or plasma. The methods involving acid hydrolysis and enzymatic degradation are widely used in the food industry to quantify beta-glucans in dietary products. Additionally, methods for isolation of beta-glucans and characterization of their physicochemical properties are also available and reviewed elsewhere [79].

Table 1. Assays for detection of beta-glucans in biological matrices and test-materials. LAL = Limulus amoebocyte lysate assay.

|

Assay Type/Name |

Manufacturer |

Detection Range |

Diagnostic (D), R&D (R), or Food (F) |

Type of Assay |

Reference |

|

Biochemical/Fungitell |

Associates of Cape Cod |

31.25–500 pg/mL |

D |

Modified LAL assay based on the measurement of optical density at 405 nm |

[48] |

|

Biochemical/Glucatell |

Associates of Cape Cod |

5–40 pg/mL |

R |

Modified LAL assay based on the measurement of optical density 405 nm (kinetic) or 540 nm (end-point) |

[72] |

|

ELISA/QuickDetect™ |

Biovision |

0.8–50 pg/mL |

D&R |

Sandwich ELISA detecting absorbance at 450 nm |

[75] |

|

Biochemical/ Toxinometer MT-6500 |

Fuji Film |

6–600 pg/mL |

D |

Modified turbidimetic LAL assay |

[74] |

|

Biochemical/Endosafe Nexgen-PTS |

Charles River |

10–1000pg/mL |

R |

Modified LAL, cartridge-based dedicated spectrophotometric assay |

[80] |

|

Chemical&Enzymatic/β-glucan yeast & mushroom |

Megazyme |

1 g/100 g |

F |

Acid-based hydrolysis of beta-glucans, followed by enzymatic degradation and measurement of absorbance at 510 nm |

[76] |

|

Enzymatic/yeast β-glucan |

Megazyme |

1 g/100 g |

F |

Enzymatic degradation assay measuring absorbance at 510 nm |

[77] |

|

Enzymatic/ β-glucan (mixed linkage) |

Megazyme |

0.5 g/100 g |

F |

Enzymatic degradation assay measuring absorbance at 510 nm |

[78] |

Studies regarding the utility of these assays for the analysis of beta-glucan contamination in engineered nanomaterials are scarce [81]. Table 2 summarizes the experience of our laboratory (https://ncl.cancer.gov) with applying the commercial Glucatell kit to screen commercial and preclinical, research-grade nanoparticle formulations for the presence of beta-glucans. The detailed experimental procedure, materials and supplies, reagent volumes, and assay incubation temperature and times are described in NCL protocol STE-4, available for download online (https://ncl.cancer.gov/sites/default/files/protocols/NCL_Method_STE-4.pdf). In our studies, the levels of beta-glucans in tested formulations varied widely from undetectable (<2.5 pg/mg) to 181,000 pg/mg of the API (Table 2). Even though some of these levels may appear high (e.g., 181,000 pg/mg), when these nanomaterials are dosed at their intended therapeutic doses, the amounts of injected beta-glucans do not exceed levels detected in the blood of healthy individuals stemming from dietary sources (see approach 4 below and reference [81] for details). Therefore, it is important to consider the data generated from beta-glucan quantification assays in the context of the dose of the nanoparticle-based product. The results obtained in our laboratory (Table 2) also demonstrate that, similarly to the experience with LAL assays [2,68–70,81,82], nanoparticles may interfere with beta-glucan detection and a valid response is not always observed at the lowest tested dilution. Therefore, inhibition/enhancement controls are important to verify the validity of the test-results.

Table 2. Levels of beta-glucans in various formulations. Three dilutions (5, 50, and 500-fold) of the stock nanomaterial were prepared in pyrogen-free water for all formulations and tested with the commercial factor-C-depleted LAL assay (GlucatellÒ) using the procedure detailed in https://ncl.cancer.gov/sites/default/files/protocols/NCL_Method_STE-4.pdf. The results were normalized to provide beta-glucan levels in picograms per milligram of active pharmaceutical ingredient (API). The spike recovery and inhibition/enhancement control (IEC) requirements for the LAL assay were used to evaluate the performance of the Glucatell assay. The IECs were prepared by spiking a known concentration of beta-glucan standard into the test sample at each dilution. A recovery of 50–200% was considered acceptable, whereas recovery outside of this range suggested nanoparticle interference; consequently, the data from dilutions demonstrating unacceptable spike recovery were considered invalid and excluded from the analysis. The data presented are from the lowest dilution that did not interfere with the assay. BLOQ = below the assay lower limit of quantification (undetectable); SPIO = superparamagnetic iron oxide; PEG = poly(ethylene glycol).

|

Platform |

API or *Active Component |

β-Glucan Conc., pg/mg API (Spike Recovery, %) |

Lowest Dilution with Acceptable Spike Recovery |

|

Nano-albumin |

Paclitaxel |

5.84 (123) |

5 |

|

Liposome |

Amphotericin |

21.3 (142) |

5 |

|

PEG-liposome |

Doxorubicin |

154 (120) |

50 |

|

SPIO |

Iron |

10.2 (133) |

50 |

|

Nanorods |

*Gold |

38.5 (70) |

50 |

|

Polymer-Antibody-Drug Conjugate |

Cisplatin |

181,000 (168) |

50 |

|

Polysaccharide Nanoparticles |

Paclitaxel |

BLOQ (104) |

500 |

|

Nanogel |

Nanogel |

109 (56) |

50 |

|

Polymeric Nanoparticle |

Iodine |

21.9 (59) |

50 |

|

Polymeric Nanoemulsion |

Propofol |

117 (111) |

500 |

|

Nanocrystal |

Docetaxel |

129 (64) |

50 |

|

Polymeric Nanoparticle |

miRNA |

3128 (81) |

50 |

|

Polymeric Micelle |

Paclitaxel |

1179 (62) |

500 |

|

PEG-oligo(FdUMP) |

FdUMP |

4.5 (93) |

5 |

|

Polymeric Micelle |

Neoantigen |

BLOQ (64) |

5 |

A variety of approaches have been developed by researchers to overcome the test material’s interference with LAL assays for the quantification of endotoxins, should IEC reveal such interference [2,68,81,82]. One of the most straightforward approaches is to increase the dilution of the test sample. However, there are strict rules for diluting test-samples so as not to undermine the validity of the test results [9]. Specifically, in the case of endotoxin, all dilutions should not exceed the so-called maximum valid dilution (MVD) calculated according to the following formula, MVD = (EL × sample concentration)/λ, where EL is the endotoxin limit and lambda (λ) is the assay sensitivity [9]. The EL is specific to each formulation and is calculated according to the formula EL = K/M, where K is the threshold pyrogenic dose (5 EU/kg for all routes of administration except for the intrathecal route, and 0.2 EU/kg for the intrathecal route) and M is the maximum dose administered in a single hour [9]. Unlike endotoxins, the threshold pyrogenic dose of beta-glucans is not established, and it complicates the estimation of the MVD. This remains one of the current limitations in the methodology for beta-glucan detection―the lack of rules for the estimation of a valid dilution range which would allow for increased dilution to overcome nanoparticle interference with the assay. Even though the use of the lowest, non-interfering dilution is desirable, it is not always practical. Studies to understand safe levels of beta-glucans and establish their threshold dose would aid with experimental design and MVD estimation. Such studies would also help to improve current approaches for data interpretation.

3. Data Interpretation

No compendial procedure or criteria are currently available for the estimation of acceptable levels of β-(1-3)-d-glucans in pharmaceutical products. Below, we describe several approaches proposed by ourselves [81] and others [32,48,83,84].

Approach 1 [83]: This is a risk-based approach that is based on the ICHQ3(R6) recommendations for establishing exposure limits to solvent impurities in drug products [85]. It includes a calculation of the permissible daily exposure (PDE) according to the following formula:

PDE = (NOAEL × weight adjustment)/(F1 × F2 × F3 × F4 × F5), where NOAEL is the no-observed-adverse-effect level derived from a toxicity study, F1 is an animal to human conversion factor, F2 is an inter-human variability factor, F3 is a subacute to chronic exposure factor, F4 is the severity of toxicity factor, and F5 is the lowest observed adverse effect level (LOAEL) to NOAEL conversion factor. The values of F1–F5 factors are 5, 10, 10, 2, and 10 for F1, F2, F3, F4, and F5, respectively.

Approach 2 [48,84]: According to this approach, the levels of beta-glucans should remain in the range of endogenous levels. The endogenous level in a healthy individual is less than 60 pg/mL.

Approach 3 [83]: This is a case-by-case approach that considers both PDE and endogenous levels. This approach considers individual characteristics of the product, such as format (IgG, IgE, fusion protein, etc.), origin (human or non-human), and immune-modulatory mechanism of action, and indication, the immunological status of the patient population, route, and frequency of administration.

Approach 4 [81]: This approach estimates the dose of beta-glucans that would be injected with each dose of nanomaterial and converts it to the beta-glucan quantity per milliliter of blood. It is based on several assumptions: (a) an average adult weight is 70 kg; (b) the blood volume of such an adult is 5.6 L (or 8% of the bodyweight); and (c) the entire injected dose stays in the circulation. The estimated amount of beta-glucans per one milliliter of blood is next compared to the limit (70 pg/mL) used in the clinical diagnostic Fungitell assay where beta-glucan levels are indicative of fungal infection. For example, if the level of beta-glucan is 100 pg/mL of a nanoformulation containing 1 mg/mL of API and the API dose is 1 mg/kg, then the beta-glucan dose is 100 pg/kg; 100 pg × 70 kg = 7000 pg of beta-glucan per 5600 mL of blood. After conversion to the amount per milliliter of blood, the result is 1.25 pg/mL, which is less than 70 pg/mL. Therefore, this would be considered within normal levels of beta-glucans present in the blood from dietary sources.

Approach 5 [32]: This approach estimates that a single dose of 500 ng of beta-glucans results in a plasma concentration of ~100 pg/mL. The same reference indicates that this level is acceptable by the UK Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency.