Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Conner Chen and Version 1 by Sinziana Ionescu.

Tuberculosis is a common systemic infection with the bacteria Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which is primarily found in the lungs and causes caseous inflammation in lung tissue and other organs. Tuberculosis is an infectious disease that spreads via the air. Tuberculosis is an endemic disease in developing countries, due to the wide spread of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), it might represent a problem in developed countries, as well. Only around one-fifth of patients diagnosed with abdominal TB have pulmonary disease.

- tuberculosis

- differential

- diagnosis

- peritonitis

- lymphadenopathy

- granuloma

- nodules

- cyst

- laparotomy

- laparoscopy

1. General Features Regarding the Diagnosis of Abdominal Tuberculosis

The research conducted found several main ideas regarding the manifestations and the differential diagnosis workup. The clinical forms of abdominal TB can be grouped, with the help of the algorithm described by [1], into five categories: first, peritonitis with its two forms: (a) “wet”, requiring proper diagnostic aspiration, and laparoscopy, and (b) “dry/fixed”, which requires endoscopy. Second, there is lymphadenopathy, which can be further described with ultrasound-guided aspiration and laparoscopy. Third, there is the intestinal set of lesions that are seen with endoscopy, and fourth, there are the lesions described at the level of the solid organs, where a biopsy can be performed. As a last resort, in cases that have not concluded any diagnosis, regardless of the set of investigations performed, there is the indication for laparotomy, with consequent pathology examination from the tissue fragments retrieved.

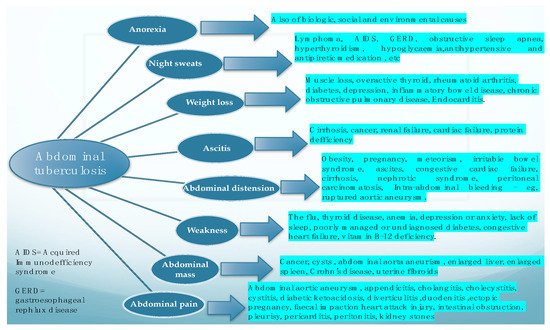

In a literature review performed by [2] in 2004, in which the authors looked at the main features of the cases suffering from abdominal tuberculosis, the most frequently found features were ascites, weight loss, weakness, abdominal mass, abdominal pain, abdominal distention, anorexia, and night sweats. This research concluded that abdominal TB should be considered in all cases with ascitis, and that the authors’ experience suggested that PCR test of the ascitic fluid obtained by ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration is a reliable method for diagnosis and should at least be attempted before surgical intervention. Figure 1. depicts the main clinical symptoms of abdominal tuberculosis and also basic data for their differentiation.

Figure 1.

Main clinical manifestations of abdominal tuberculosis, and the main differential for each of them.

Another study, which revisited an older review performed by [3], looked into the diagnostic challenges of abdominal tuberculosis, as it does not present with specific features and is, thus, regarded as a great mimicker. Imaging is described as highly important in the early recognition of the disease.

In “stubborn” cases, presenting with difficult differential diagnostic issues, with many investigations and little orientation towards an incriminating pathogen, a review done by [4] indicated the importance of laparoscopy in the diagnosis of abdominal tuberculosis. Furthermore, apart from mentioning common literature themes on the subject, such as the fact that abdominal pain and weight loss are commonly encountered and that TB presents non-specifically, this literature search emphasized the fact that the most consistent lab findings (in a percentage of more than 90%) were low hemoglobin and raised C-reactive protein. In the general context that the Mantoux tuberculin test was positive only in a small percentage, and where Ziehl Neelsen staining of the ascitic fluid was also negative in all patients, laparoscopy proved useful in yielding a diagnosis in 92% of the cases.

An analysis made in 1994 [4] reviewed the features of abdominal TB and found that 10 to 30% of the patients with lung TB also had abdominal involvement, and that the incidence was higher in immigrants from developing countries and patients with AIDS. The idea was underlined further by the fact that in HIV-infected patients the disease is of a rapidly progressing nature and often of a fatal outcome, as diagnosis is difficult and delayed, while treatment is mostly medical but can also be surgical.

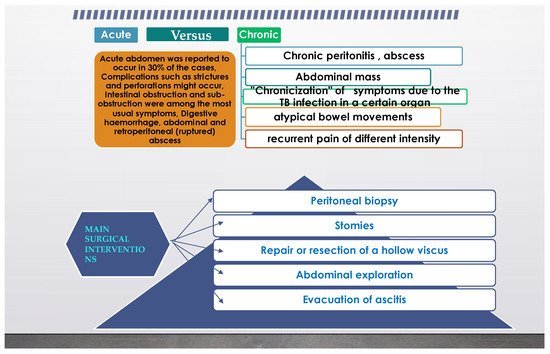

From the previous paragraph, it can be inferred that abdominal TB can also represent a surgical problem, and in another review from [5] it was stated that even an astute surgeon can find a challenge in the diagnosis. It is not uncommon for extrapulmonary TB to present as an acute abdomen in surgical emergencies, such as perforations and obstructions of the bowel. Moreover, abdominal TB, in its different forms was found more often as an etiology for a chronic abdomen. The paper concluded that abdominal TB should always be considered one of the differential diagnoses of acute or chronic abdomen in endemic areas. TB peritonitis can be caused by reactivation of a latent TB focus, by the discharge of caseous material from diseased lymph nodes, or TB salpingitis in females. In the “wet” ascitic type, which is found in the majority of cases, there is a large amount of fluid that can be free or loculated. In the “fibrotic” fixed type, there is a mesenteric and omental thickening, and masses can be found with matted bowel loops and sometimes loculated ascitis. In the “dry” or plastic-type, there are caseous nodules, a fibrous peritoneal reaction, and dense adhesions. The most commonly encountered surgical settings in a patient with abdominal tuberculosis are summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Common surgical setting characteristics in abdominal tuberculosis.

When TB associates with ascitis, ultrasound can detect even a small amount and show fine, multiple strands of fibrin, septations, and debris. A computed tomography exam can show the high density of fibrin and cellular debris or water density in the initial transitive phase, or even the fat fluid level due to chylous ascitis. A magnetic resonance imaging exam can show delayed enhancement (15–20 min) after i.v. contrast.

When studying the multifaceted lesions of peritoneal carcinomatosis and its mimickers in a review from 2014 [6], the main aspect underlined was that invasive peritoneal disease included more than just peritoneal carcinomatosis, and a rigorous CT analysis may also show pseudomyxoma peritonei, peritoneal lymphomatosis, tuberculosis, peritoneal mesothelioma, diffuse peritoneal leyomyomatosis, and benign splenosis.

Radiologic imaging should also be included in the workup for abdominal tuberculosis; CT is preferred, because it allows for the assessment of lymphadenopathy, ascites, and peritoneal and solid organ involvement.

Additional imaging modalities may be beneficial: ultrasound may be used to detect lymphadenopathy, ascites, and peritoneal and intestinal thickening, while a barium enema may be used to detect mucosal ulcerations, strictures, and ileocecal valve incompetence.

An abdominal X-ray can be helpful in determining air–fluid levels (during the presentation of intestinal obstruction) and liver and/or ureter calcifications.

2. Different Intra-Abdominal Organs and Their Involvement

The differential diagnosis between abdominal TB and other important diseases was taken into consideration in various studies, considering a particular organ or form in which TB manifests, as described in the following subsections.

2.1. Oesophageal TB

Oesophageal TB is described as secondary to advanced forms of pulmonary or mediastinal tuberculosis. The sources can be tuberculous laryngitis, caseating lymph nodes, vertebral body infection, and also the lymphatic/hematogenous route. Barium study shows extrinsic compression by enlarged nodes, ulcerations, smooth strictures, mucosal irregularity, traction diverticula, and fistulae. CT assists in identifying the peripheral extension of the disease.

According to the research carried out by [7], oesophageal TB can manifest as dysphagia. Various other details related to oesophageal TB, from the scarce literature on the subject, can be found in Table 1.

Table 1. Oesophageal tuberculosis and a comparison between the findings from different studies.

| Name of the Study, Journal Where It Was Published, and Year | Investigations Used, Purpose of the Study | Findings | Number of Cases |

|---|

| Study | Key-Features | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Kocaman, Turk. J. Gastroenterol., 2013 [8] |

Endosonography and elastography in the diagnosis of esophageal tuberculosis | Esophageal tuberculosis | Case report |

| Form of TB Encountered in the Study | |||

| V. D. Plat, Journal Of Surgery, 2017 [9] |

Comparing endoscopic repair with surgical repair in brochoesophageal fistulas | Fistulas were caused by postoperative complications or pulmonary TB | 16 cases |

Half of the instances identified in the reviewed literature were associated with pulmonary tuberculosis.

Frequently presenting with multi-cystic pancreatic mass (81%), the most prevalent anatomic regions of the pancreas were the head (73%), tail (18%), and body (9%) of the pancreas.

According to a study conducted by [27], clinical suspicion and an appropriate diagnostic method, including FNAB of the pancreatic lesion, are required to prevent undergoing a needless laparotomy.

X-ray imaging of pancreatic tuberculosis reveals a hypodense lesion with an uneven edge, and pancreatic enlargement with/without peripancreatic node expansion.

According to [28], cystic lesions discovered in and surrounding the peritoneal cavity can frequently be difficult to diagnose, due to an extensive overlap.

When approaching a cystic lesion, it is critical to analyze the following imaging characteristics: cyst content, locularity, wall thickness, and the existence of internal septa, solid components, calcifications, or any related enhancements.

While conclusive diagnosis is not always feasible following imaging, a careful examination of the imaging appearance, location, and connection to neighboring tissues can assist in narrowing the differential diagnosis. Table 5 summarizes the referred studies and their main research features on pancreatic tuberculosis.

Table 5. Pancreatic TB.

| Main Author | Main features of the research | Main aspects followed | |

| Ray et al., JOP, 2012 [29] |

Pancreatic and peripancreatic nodal tuberculosis in immunocompetent patients: report of 3 cases | Description of pancreatic TB with contrast-enhanced ultrasound | |

| Irfan M. Monaldi Arch. Chest Dis. 2013 [30] |

Tb pancreatitis complicating with a ruptured splenic artery pseudoaneurysm | Emergency laparotomy for haemorrhage | |

| D. Cruz S. | Pancreatic TB | FNA biopsy | |

| S.K. Jain, | |||

The American Journal of Gastroenterology, 2002 [7] |

Upper endoscopy Pathology exam Cytology |

Pts with esophageal TB constituted 0.5% of pts with dysphagia and 1.3% of all pts with abnormal esophagoscopic findings | 12 cases |

| M.C. Borges, Dig. Dis. Sci., 2009 [10] |

Evaluate the role of PCR in the etiology of ulcers in HIV-1 infected pts | 96 biopsies from HIV infected pts were processed by specific PCR | 79 cases |

| S.Jain, Acta Cytol., 1999 [11] |

To study the utility of endoscopic cytology in the diagnosis of esophageal TB in clinically unsuspected cases | 228 cases of esophageal lesions | 8 cases |

2.2. Gastroduodenal TB

Gastroduodenal tuberculosis presents in a variety of ways, including stomach abdominal pain and dyspepsia, as well as obstruction of the gastric outlet. Upper digestive endoscopy can produce ulcer lesions, narrowing, and fistulas, which might require further investigations and treatment procedures, as was presented by [11]. Table 2 further describes the comparative features of gastroduodenal tuberculosis.

Table 2. Gastroduodenal tuberculosis: examples of literature studies and their key features.

| Review | Key-Features | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| JOP, | |||

| 2003 | |||

| [31] | |||

| P. Chaudhary, Indian Journal of Tuberculosis, 2019 [12] |

Gastric TB is rare | ||

| Poras Chaudhary, Indian Journal of Tuberculosis, 2021 [17][16] | It mimics gastric carcinoma Responds well to conservative management Requires surgery for complications |

||

| Rare, commonly misdiagnosed, curable with chemotherapy, surgery for complications | |||

| MDCT Findings of splenic pathology, Sangster, 2021 [23] |

Microabscess, splenomegaly | M. Barat, Diagnostic and Interventional Imaging, 2017 [13] |

Jan Rakinic, Advances in Surgery, Volume 52, Issue 1, 2018 [18][17]Duodenal Tb is rare, the disease more commonly affects the ileocecum, colon, and jejunum, while more than 90% of duodenal TB was also found to have co-infections with other parts of the intestine On CT, duodenal Tb presents as strictures, extrinsic compression, polypoidal intraluminal mass, and duodenal ulcerations, associated with multiple hypoattenuating lymph nodes |

| S. Srisajjakul, Clinical Imaging, 2016 [14] |

Duodenitis Aortoduodenal fistula |

CT imaging of the stomach can reveal the hypertrophic features of tuberculous pyloric stenosis in its late stages. Although the presence of a sinus tract and fistula is uncommon, they are indicative of tuberculosis. The gastric antrum and distal body are the most frequently involved structures. The hypertrophic form can exhibit severe and diffuse wall thickening on imaging. Antral narrowing can occur as a result of ulceration and fibrosis.

The duodenum is most frequently affected by the extrinsic compression caused by adjacent lymphadenopathy, which manifests as obstruction and is easily detected on CT scans. Additionally, the duodenum may exhibit intrinsic hypertrophic involvement, which is visible on CT as thickening of the duodenal walls. Ulcers can result in strictures and fistulae, similar to the case of the stomach, which are readily visible in barium studies.

2.3. Jejunal, Ileal, and Colonic TB

The small bowel mesentery is commonly involved in patients with peritoneal TB. Investigations have shown nodular lesions, solid or cystic, forming from lymph nodes or abscess, and mesenteric thickening (of more than 15 mm for diagnosis purposes), while the mesentery appears hypoechoic, due to fat deposition from lymphatics. An ultrasound exam can find a stellate sign with fixed loops of bowel and with the mesentery standing out as spikes radiating from the root of the mesentery. The “club sandwich” or “slice bread sign” describes the focal ascitis between radially oriented bowel loops, due to exudation from inflamed bowel loops or ruptured lymph nodes. Computed tomography shows a thickened mesentery, as has been previously mentioned, with increased vascularity and tethering of bowel loops, forming an abdominal mass.

Intestinal TB is mainly located in the ileocecal area, in isolation or as part of a multifocal involvement. Findings of a barium study can be labelled, first of all, as “highly suggestive”, when one or more of the following features are seen: deformed ileocecal valve with dilated terminal ileum, contracted cecum with an abnormal ileocecal valve and/or terminal ileum, stricture of the ascending colon with shortening and involvement of the ileocolic region. Other traits are “suggestive”, but less specific, such as a contracted cecum, ulcerations or narrowing of the terminal ileum, stricture of the ascending colon, multiple areas of dilation, and narrowing or matting of small bowel loops. A CT scan of the ileocecal region can contribute further information on the aspect of this bowel segment and its appearance, the main differential is with Crohn’s disease, as can be seen in the overlap subsection of this article. Some studies affirmed that with TB, night sweats are more common, while with Crohn’s, diarrhea and perianal disease are to be found more often, as described by [14].

In the situation of an immunosuppressed patient, enteritis can also be caused by Mycobacterium avium intracellulare complex infection (MAC), which can occur in cases of MAC disseminated infection, in patients with AIDS, or with transplant recipients. Diagnosis is established by isolating the organisms from blood cultures, and when MAC enteritis is suspected stool cultures are useful. MAC infection can mimic Whipple disease, as was found by [15].

The large bowel is involved in around 9-10% of cases without small bowel involvement. A scan can show segmental long/short involvement, spiculation, spasm, rigidity and ulceration, inflammatory polyps, perforation, fistulae, and pericolic abscess.

2.4. Rectal TB

Rectal tuberculosis is a rare occurrence and data with more info can be found in Table 3.

Due to its unique epidemiological characteristics, it requires specialized medical care, and surgery is rarely needed.

Diagnosis is frequently delayed.

Rectal tuberculosis patients are known to have some risk factors, including concomitant diseases linked with a variety of defective host–defense mechanisms, such as acquired immunodeficiency syndrome or complement insufficiency.

Rectal TB is more prevalent in females than males.

Hematochezia is the most frequently presenting symptom encountered.

A definitive diagnosis requires histopathologic evidence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacillus.

Rectal tuberculosis is treatable with antituberculous medication if a correct diagnosis has been obtained.

Surgery is indicated in cases of diagnostic impasses, intractable disease, and complications.

2.5. Liver and Splenic TB

Liver and spleen involvement is common in milliary TB or in the portal vein in gastrointestinal lesions.

The form encountered can be micronodular, as is the case of milliary TB, with the ultrasound showing a bright liver and spleen and the computed tomography showing small nodules, which are not easily seen. If found, hepatosplenomegaly can be homogenous or heterogeneous.

The macronodular form is another variation of this type and is seen on ultrasound as hypoechoic lesions, sometimes hyperechoic, with or without calcification, and, un-commonly, a “honeycomb” aspect is found. Computed tomography shows a low-density lesion (15–45 Hounsfield units), with a minimal central enhancement and moderate peripheral enhancement. Magnetic resonance imaging shows a hypointense lesion on T1-weighted images with a hypointense rim and a iso- to hyperintense lesion on T2-weighted images with a less intense rim.

Various studies, among which we refer to [21][20], have described the use of elastography in abdominal tuberculosis, as a means of diagnosis of portal hypertension of a benign etiology.

During a review looking at the splenic forms of TB, [22] found that splenic involvement occurs more in males, in an age group of 19–53, that fever of unknown origin is the typical presentation, and that it can present with small splenomegaly, splenic abscess, associated with ascitis or not.

Studies on key-findings in the literature searched on the topic of “splenic tuberculosis” were mentioned in Table 4.

Table 4. Splenic tuberculosis: literature studies and their key features.

| Study | |

|---|---|

| A review of the cysts of the spleen, Khan, 2016 [24] |

Peliosis |

| Improving diagnosis of atraumatic splenic lesions, Ricci, 2016 [25] |

Calcified granuloma and peliosis |

| Splenic tuberculosis: a comprehensive review of literature, Gupta, 2018 [26] |

Small splenomegaly, abscess+/- ascitis |

| Hypersplenism secondary to splenic tuberculosis, Ais, 1993 [27] |

Hypersplenism |

2.6. Pancreatic TB. Approach to Cystic Lesions. Pancreatic Cysts

Pancreatic tuberculosis is another uncommon entity that mimics a pancreatic tumor.

2.7. Calcified Lymphadenopathy and Tuberculous Lymphadenitis

One of the most frequent indications for endoscopic ultrasound-guided tissue biopsy is to elucidate the source of suspicious lymphadenopathy. Even if most cases are benign and auto-limiting, patients with deep-seated lymph nodes living in TB-endemic areas, or with suspected malignancy, require tissue diagnosis to guide treatment. TB lymphadenitis can vary from increased numbers of normal size lymph nodes, to massive con-glomerate/matted nodes, to peri adenitis. The sites of lymph nodes involving secondary to lymphatic drainage from the bowel are mesenteric periportal, anterior pararenal, upper para-aortic, and lesser omental regions. Hematogenous spread might lead to the following sites of infected lymph nodes: mesenteric, lesser omental, anterior pararenal, and upper and lower paraaortic. Direct spread can lead to infection of lymph nodes from adjacent organs. According to the findings from a study by [32], tuberculous lymphadenitis can appear on a CT scan as: (a) in the first stage with homogenous enhancement, (b) in the second stage as central caseous necrosis and peripheral rim enhancement, and (c) in the final stage as fibrosis and calcifications.

Magnetic resonance imaging has proven useful in showing the relationship of the lymph nodes to the vessels, ducts, and, also for differentiating necrotic peripancreatic nodes from an adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas, as will be seen further on.

Several types of research of tuberculous endemic regions reported between approximately one-third and one half of cases as tuberculous adenitis, with a diagnostic yield of 89%. In patients presenting with a high clinical suspicion of TB, the study reported tuberculous adenitis in over 70% of abdominal lymphadenopathies. Fine needle aspiration guided by endoscopic ultrasound (EUS-FNA) [33] had a sensitivity of 86%, a specificity of 100%, and 91% negative predictive values for TB. The first rationale of the study was that TB remains a serious menace to public health, but hepatic and pancreatic TB are rare, and, therefore, the preoperative diagnosis of pancreatic TB remains a great challenge. The lessons learned in the research conducted by [34] were connected to calcification, in both pancreatic lesions and peripancreatic lymph nodes, as a suggestion of pancreatic TB, rather than pancreatic malignancy.

Tuberculous lymphadenitis can also be found in the clinical setting of a severe complication such as is the case of obstructive jaundice secondary to TB, an extremely rare entity that can be caused by TB enlargement of the head of the pancreas, TB lymphadenitis, TB stricture of the biliary tree, or a TB mass in the retroperitoneum, as will be seen in another subsection. The investigations employed were ultrasound, computed tomography, ERCP and CEA, and CA 19-9, which were normal, as well as PCR testing [34].

References

- Abu-Zidan, F.M.; Sheek-Hussein, M. Diagnosis of abdominal tuberculosis: Lessons learned over 30 years: Pectoral assay. World J. Emerg. Surg. 2019, 14, 33.

- Uzunkoy, A. Diagnosis of abdominal tuberculosis: Experience from 11 cases and review of the literature. World J. Gastroenterol. 2004, 10, 3647.

- Debi, U. Abdominal tuberculosis of the gastrointestinal tract: Revisited. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 14831.

- Rai, S.; Thomas, W.M. Diagnosis of abdominal tuberculosis: The importance of laparoscopy. JRSM 2003, 96, 586–588.

- Pattanayak, S.; Behuria, S. Is abdominal tuberculosis a surgical problem? Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 2015, 97, 414–419.

- Diop, A.D.; Fontarensky, M.; Montoriol, P.-F.; da Ines, D. CT imaging of peritoneal carcinomatosis and its mimics. Diagn. Interv. Imaging 2014, 95, 861–872.

- Jain, S.K.; Jain, S.; Jain, M.; Yaduvanshi, A. Esophageal tuberculosis: Is it so rare? Report of 12 cases and review of the literature. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2002, 97, 287–291.

- Kocaman, O.; Arabaci, E.; Turkdogan, K.; Danalioglu, A.; Senturk, H.; Ince, A.; Yildiz, K. Endosonography and elastography in the diagnosis of esophageal tuberculosis. Turk. J. Gastroenterol. Off. J. Turk. Soc. Gastroenterol. 2013, 24, 290–291.

- Plat, V.D.; Bootsma, B.T.; van der Wielen, N.; Straatman, J.; Schoonmade, L.J.; van der Peet, D.L.; Daams, F. The role of tissue adhesives in esophageal surgery, a systematic review of literature. Int. J. Surg. 2017, 40, 163–168.

- Borges, M.C.; Colares, J.K.B.; Lima, D.M.; Fonseca, B.A.L. Advantages and Pitfalls of the Polymerase Chain Reaction in the Diagnosis of Esophageal Ulcers in AIDS Patients. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2009, 54, 1933–1939.

- Jain, S.; Kumar, N.; Das, D.K.; Jain, S.K. Esophageal Tuberculosis. Acta Cytol. 1999, 43, 1085–1090.

- Chaudhary, P.; Khan, A.Q.; Lal, R.; Bhadana, U. Gastric tuberculosis. Indian J. Tuberc. 2019, 66, 411–417.

- Barat, M.; Dohan, A.; Dautry, R.; Barral, M.; Boudiaf, M.; Hoeffel, C.; Soyer, P. Mass-forming lesions of the duodenum: A pictorial review. Diagn. Interv. Imaging 2017, 98, 663–675.

- Srisajjakul, S.; Prapaisilp, P.; Bangchokdee, S. Imaging spectrum of nonneoplastic duodenal diseases. Clin. Imaging 2016, 40, 1173–1181.

- Kedia, S.; Das, P.; Madhusudhan, K.S.; Dattagupta, S.; Sharma, R.; Sahni, P.; Makharia, G.; Ahuja, V. Differentiating Crohn’s disease from intestinal tuberculosis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 25, 418–432.

- Chaudhary, P.; Nagpal, A.; Padala, S.B.; Mukund, M.; Bansal, L.K.; Lal, R. Rectal tuberculosis: A systematic review. Indian J. Tuberc. 2021.

- Rakinic, J. Benign Anorectal Surgery. Adv. Surg. 2018, 52, 179–204.

- Puri, A.S.; Vij, J.C.; Chaudhary, A.; Kumar, N.; Sachdev, A.; Malhotra, V.; Malik, V.K.; Broor, S.L. Diagnosis and outcome of isolated rectal tuberculosis. Dis. Colon Rectum 1996, 39, 1126–1129.

- Chaudhary, A.; Gupta, N.M. Colorectal tuberculosis. Dis. Colon Rectum 1986, 29, 738–741.

- Patil, S.; Shah, A.G.; Bhatt, H.; Nalawade, N.; Mangal, A. Tuberculosis of rectum simulating malignancy and presenting as rectal prolapse—A case report and review. Indian J. Tuberc. 2013, 60, 184–185.

- Aris, F.; Naim, C.; Bessissow, T.; Amre, R.; Artho, G.P. AIRP Best Cases in Radiologic-Pathologic Correlation: Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare Complex Enteritis. Radiographics 2011, 31, 825–830.

- Berzigotti, A. Non-invasive evaluation of portal hypertension using ultrasound elastography. J. Hepatol. 2017, 67, 399–411.

- Sangster, G.P.; Malikayil, K.; Donato, M.; Ballard, D.H. MDCT Findings of Splenic Pathology. Curr. Probl. Diagn. Radiol. 2021.

- Khan, Z.; Chetty, R. A review of the cysts of the spleen. Diagn. Histopathol. 2016, 22, 479–484.

- Ricci, Z.J.; Oh, S.K.; Chernyak, V.; Flusberg, M.; Rozenblit, A.M.; Kaul, B.; Stein, M.W.; Mazzariol, F.S. Improving diagnosis of atraumatic splenic lesions, part I: Nonneoplastic lesions. Clin. Imaging 2016, 40, 769–779.

- Gupta, A. Splenic tuberculosis: A comprehensive review of literature. Pol. Prz. Chir. 2018, 90, 49–51.

- Ais, G.; Ortega, M.; Esteban, F.; González, A.; Manzanares, J. Hypersplenism secondary to splenic tuberculosis. Rev. Esp. Enferm. Dig. Organo Of. Soc. Esp. Patol. Dig. 1993, 83, 397–399.

- Cho, S.B. Pancreatic tuberculosis presenting with pancreatic cystic tumor: A case report and review of the literature. Korean J. Gastroenterol. Taehan Sohwagi Hakhoe Chi 2009, 53, 324–328.

- Ray, S.; Das, K.; Mridha, A.R. Pancreatic and peripancreatic nodal tuberculosis in immunocompetent patients: Report of three cases. JOP J. Pancreas 2012, 13, 667–670.

- Irfan, M.; Thiavalappil, F.; Nagaraj, J.; Brown, T.H.; Roberts, D.; Mcknight, L.; Harrison, N.K. Tuberculous pancreatitis complicated by ruptured splenic artery pseudoaneurysm. Monaldi Arch. Chest Dis. 2013, 79, 134–135.

- D’Cruz, S.; Sachdev, A.; Kaur, L.; Handa, U.; Bhalla, A.; Lehl, S.S. Fine needle aspiration diagnosis of isolated pancreatic tuberculosis. A case report and review of literature. JOP J. Pancreas 2003, 4, 158–162.

- Ladumor, H.; Al-Mohannadi, S.; Ameerudeen, F.S.; Ladumor, S.; Fadl, S. TB or not TB: A comprehensive review of imaging manifestations of abdominal tuberculosis and its mimics. Clin. Imaging 2021, 76, 130–143.

- Fritscher-Ravens, A.; Ghanbari, A.; Topalidis, T.; Pelling, M.; Kon, O.M.; Patel, K.; Arlt, A.; Bhowmik, A. Granulomatous mediastinal adenopathy: Can endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration differentiate between tuberculosis and sarcoidosis? Endoscopy 2011, 43, 955–961.

- Liang, X.; Huang, X.; Yang, Q.; He, J. Calcified peripancreatic lymph nodes in pancreatic and hepatic tuberculosis mimicking pancreatic malignancy: A case report and review of literature. Medicine 2018, 97, e12255.

More