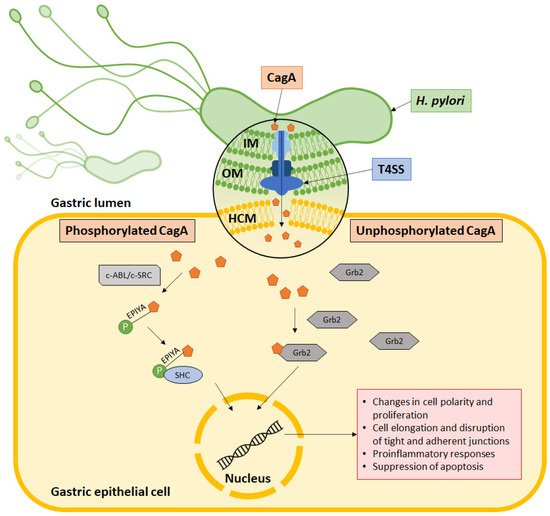

Helicobacter pylori is well established as a causative agent for gastritis, peptic ulcer, and gastric cancer. Armed with various inimitable virulence factors, this Gram-negative bacterium is one of few microorganisms that is capable of circumventing the harsh environment of the stomach. The unique spiral structure, flagella, and outer membrane proteins accelerate H. pylori movement within the viscous gastric mucosal layers while facilitating its attachment to the epithelial cells. Furthermore, secretion of urease from H. pylori eases the acidic pH within the stomach, thus creating a niche for bacteria survival and replication. Upon gaining a foothold in the gastric epithelial lining, bacterial protein CagA is injected into host cells through a type IV secretion system (T4SS), which together with VacA, damage the gastric epithelial cells.

- Helicobacter pylori

- flagella

- outer membrane protein

- CagA

- VacA

- type IV secretion system

- pathogenesis

1. H. pylori Structures Facilitate Bacterial Motility in the Thick Mucosal Layers

2. OMPs Facilitate Bacterial Attachment to the Gastric Epithelial Cells

3. H. pylori Urease Neutralizes Acidic pH

4. H. pylori Evades Host Immune Response

5. Type IV Secretion System Penetrates Gastric Epithelial Cells

6. CagA Perturbs Normal Cell Activities

References

- Sycuro, L.K.; Pincus, Z.; Gutierrez, K.D.; Biboy, J.; Stern, C.A.; Vollmer, W.; Salama, N.R. Peptidoglycan Crosslinking Relaxation Promotes Helicobacter pylori’s Helical Shape and Stomach Colonization. Cell 2010, 141, 822–833.

- Fung, C.; Tan, S.; Nakajima, M.; Skoog, E.C.; Camarillo-Guerrero, L.F.; Klein, J.A.; Lawley, T.D.; Solnick, J.V.; Fukami, T.; Amieva, M.R. High-resolution mapping reveals that microniches in the gastric glands control Helicobacter pylori colonization of the stomach. PLoS Biol. 2019, 17, e3000231.

- Gu, H. Role of Flagella in the Pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori. Curr. Microbiol. 2017, 74, 863–869.

- Fagoonee, S.; Pellicano, R. Helicobacter pylori: Molecular basis for colonization and survival in gastric environment and resistance to antibiotics. A short review. Infect. Dis. 2019, 51, 399–408.

- Hathroubi, S.; Zerebinski, J.; Ottemann Karen, M.; Freitag Nancy, E.; Hengge, R.; Cover, T. Helicobacter pylori Biofilm Involves a Multigene Stress-Biased Response, Including a Structural Role for Flagella. MBio 2018, 9, e01973-18.

- Bauwens, E.; Joosten, M.; Taganna, J.; Rossi, M.; Debraekeleer, A.; Tay, A.; Peters, F.; Backert, S.; Fox, J.; Ducatelle, R.; et al. In silico proteomic and phylogenetic analysis of the outer membrane protein repertoire of gastric Helicobacter species. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 15453.

- Alm, R.A.; Bina, J.; Andrews, B.M.; Doig, P.; Hancock, R.E.W.; Trust, T.J. Comparative Genomics of Helicobacter pylori: Analysis of the Outer Membrane Protein Families. Infect. Immun. 2000, 68, 4155.

- Oleastro, M.; Ménard, A. The Role of Helicobacter pylori Outer Membrane Proteins in Adherence and Pathogenesis. Biology 2013, 2, 1110–1134.

- Mahdavi, J.; Sondén, B.; Hurtig, M.; Olfat, F.O.; Forsberg, L.; Roche, N.; Ångström, J.; Larsson, T.; Teneberg, S.; Karlsson, K.-A.; et al. Helicobacter pylori SabA Adhesin in Persistent Infection and Chronic Inflammation. Science 2002, 297, 573–578.

- Senkovich, O.A.; Yin, J.; Ekshyyan, V.; Conant, C.; Traylor, J.; Adegboyega, P.; McGee, D.J.; Rhoads, R.E.; Slepenkov, S.; Testerman, T.L. Helicobacter pylori AlpA and AlpB Bind Host Laminin and Influence Gastric Inflammation in Gerbils. Infect. Immun. 2011, 79, 3106–3116.

- de Jonge, R.; Durrani, Z.; Rijpkema, S.G.; Kuipers, E.J.; van Vliet, A.H.M.; Kusters, J.G. Role of the Helicobacter pylori outer-membrane proteins AlpA and AlpB in colonization of the guinea pig stomach. J. Med Microbiol. 2004, 53, 375–379.

- Teymournejad, O.; Mobarez, A.M.; Hassan, Z.M.; Moazzeni, S.M.; Ahmadabad, H.N. In Vitro Suppression of Dendritic Cells by Helicobacter pylori OipA. Helicobacter 2014, 19, 136–143.

- Teymournejad, O.; Mobarez, A.M.; Hassan, Z.M.; Talebi Bezmin abadi, A. Binding of the Helicobacter pylori OipA causes apoptosis of host cells via modulation of Bax/Bcl-2 levels. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 8036.

- Gur, C.; Maalouf, N.; Gerhard, M.; Singer, B.B.; Emgård, J.; Temper, V.; Neuman, T.; Mandelboim, O.; Bachrach, G. The Helicobacter pylori HopQ outermembrane protein inhibits immune cell activities. OncoImmunology 2019, 8, e1553487.

- Eaton, K.A.; Brooks, C.L.; Morgan, D.R.; Krakowka, S. Essential role of urease in pathogenesis of gastritis induced by Helicobacter pylori in gnotobiotic piglets. Infect. Immun. 1991, 59, 2470–2475.

- Debowski, A.W.; Walton, S.M.; Chua, E.-G.; Tay, A.C.-Y.; Liao, T.; Lamichhane, B.; Himbeck, R.; Stubbs, K.A.; Marshall, B.J.; Fulurija, A.; et al. Helicobacter pylori gene silencing in vivo demonstrates urease is essential for chronic infection. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006464.

- Mégraud, F.; Neman-Simha, V.; Brügmann, D. Further evidence of the toxic effect of ammonia produced by Helicobacter pylori urease on human epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 1992, 60, 1858–1863.

- Meyer-Rosberg, K.; Scott, D.R.; Rex, D.; Melchers, K.; Sachs, G. The effect of environmental pH on the proton motive force of Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology 1996, 111, 886–900.

- Uberti, A.F.; Olivera-Severo, D.; Wassermann, G.E.; Scopel-Guerra, A.; Moraes, J.A.; Barcellos-de-Souza, P.; Barja-Fidalgo, C.; Carlini, C.R. Pro-inflammatory properties and neutrophil activation by Helicobacter pylori urease. Toxicon 2013, 69, 240–249.

- Olivera-Severo, D.; Uberti, A.F.; Marques, M.S.; Pinto, M.T.; Gomez-Lazaro, M.; Figueiredo, C.; Leite, M.; Carlini, C.R. A New Role for Helicobacter pylori Urease: Contributions to Angiogenesis. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1883.

- Lee, S.K.; Stack, A.; Katzowitsch, E.; Aizawa, S.I.; Suerbaum, S.; Josenhans, C. Helicobacter pylori flagellins have very low intrinsic activity to stimulate human gastric epithelial cells via TLR5. Microbes Infect. 2003, 5, 1345–1356.

- Luo, Y.-H.; Yan, J.; Mao, Y.-F. Helicobacter pylori lipopolysaccharide: Biological activities in vitro and in vivo, pathological correlation to human chronic gastritis and peptic ulcer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2004, 10, 2055–2059.

- Lina, T.T.; Alzahrani, S.; Gonzalez, J.; Pinchuk, I.V.; Beswick, E.J.; Reyes, V.E. Immune evasion strategies used by Helicobacter pylori. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 12753–12766.

- Andersen-Nissen, E.; Smith, K.D.; Strobe, K.L.; Barrett, S.L.R.; Cookson, B.T.; Logan, S.M.; Aderem, A. Evasion of Toll-like receptor 5 by flagellated bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 9247.

- Gringhuis, S.I.; den Dunnen, J.; Litjens, M.; van der Vlist, M.; Geijtenbeek, T.B.H. Carbohydrate-specific signaling through the DC-SIGN signalosome tailors immunity to Mycobacterium tuberculosis, HIV-1 and Helicobacter pylori. Nat. Immunol. 2009, 10, 1081–1088.

- Tan, G.M.Y.; Looi, C.Y.; Fernandez, K.C.; Vadivelu, J.; Loke, M.F.; Wong, W.F. Suppression of cell division-associated genes by Helicobacter pylori attenuates proliferation of RAW264.7 monocytic macrophage cells. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11046.

- Ramarao, N.; Meyer, T.F. Helicobacter pylori Resists Phagocytosis by Macrophages: Quantitative Assessment by Confocal Microscopy and Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting. Infect. Immun. 2001, 69, 2604–2611.

- Lekmeechai, S.; Su, Y.-C.; Brant, M.; Alvarado-Kristensson, M.; Vallström, A.; Obi, I.; Arnqvist, A.; Riesbeck, K. Helicobacter pylori Outer Membrane Vesicles Protect the Pathogen From Reactive Oxygen Species of the Respiratory Burst. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1837.

- Codolo, G.; Toffoletto, M.; Chemello, F.; Coletta, S.; Soler Teixidor, G.; Battaggia, G.; Munari, G.; Fassan, M.; Cagnin, S.; de Bernard, M. Helicobacter pylori Dampens HLA-II Expression on Macrophages via the Up-Regulation of miRNAs Targeting CIITA. Front. Immunol. 2020, 10, 2923.

- Kao, J.Y.; Zhang, M.; Miller, M.J.; Mills, J.C.; Wang, B.; Liu, M.; Eaton, K.A.; Zou, W.; Berndt, B.E.; Cole, T.S.; et al. Helicobacter pylori Immune Escape Is Mediated by Dendritic Cell–Induced Treg Skewing and Th17 Suppression in Mice. Gastroenterology 2010, 138, 1046–1054.

- Lina, T.T.; Pinchuk, I.V.; House, J.; Yamaoka, Y.; Graham, D.Y.; Beswick, E.J.; Reyes, V.E. CagA-Dependent Downregulation of B7-H2 Expression on Gastric Mucosa and Inhibition of Th17 Responses during Helicobacter pylori Infection. J. Immunol. 2013, 191, 3838–3846.

- Sarajlic, M.; Neuper, T.; Vetter, J.; Schaller, S.; Klicznik, M.M.; Gratz, I.K.; Wessler, S.; Posselt, G.; Horejs-Hoeck, J. H. pylori modulates DC functions via T4SS/TNFα/p38-dependent SOCS3 expression. Cell Commun. Signal. 2020, 18, 160.

- Lv, Y.-p.; Cheng, P.; Zhang, J.-y.; Mao, F.-y.; Teng, Y.-s.; Liu, Y.-g.; Kong, H.; Wu, X.-l.; Hao, C.-j.; Han, B.; et al. Helicobacter pylori–induced matrix metallopeptidase-10 promotes gastric bacterial colonization and gastritis. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaau6547.

- Gonzalez-Rivera, C.; Bhatty, M.; Christie, P.J. Mechanism and function of type IV secretion during infection of the human host. Microbiol. Spectr. 2016, 4.

- Frick-Cheng, A.E.; Pyburn, T.M.; Voss, B.J.; McDonald, W.H.; Ohi, M.D.; Cover, T.L. Molecular and Structural Analysis of the Helicobacter pylori Type IV Secretion System Core Complex. MBio 2016, 7, e02001-15.

- Kwok, T.; Zabler, D.; Urman, S.; Rohde, M.; Hartig, R.; Wessler, S.; Misselwitz, R.; Berger, J.; Sewald, N.; König, W.; et al. Helicobacter exploits integrin for type IV secretion and kinase activation. Nature 2007, 449, 862–866.

- Tegtmeyer, N.; Hartig, R.; Delahay, R.M.; Rohde, M.; Brandt, S.; Conradi, J.; Takahashi, S.; Smolka, A.J.; Sewald, N.; Backert, S. A Small Fibronectin-mimicking Protein from Bacteria Induces Cell Spreading and Focal Adhesion Formation. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 23515–23526.

- Ishijima, N.; Suzuki, M.; Ashida, H.; Ichikawa, Y.; Kanegae, Y.; Saito, I.; Borén, T.; Haas, R.; Sasakawa, C.; Mimuro, H. BabA-mediated Adherence Is a Potentiator of the Helicobacter pylori Type IV Secretion System Activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 25256–25264.

- Semper, R.P.; Vieth, M.; Gerhard, M.; Mejías-Luque, R. Helicobacter pylori Exploits the NLRC4 Inflammasome to Dampen Host Defenses. J. Immunol. 2019, 203, 2183.

- Hacker, J.; Kaper, J.B. Pathogenicity islands and the evolution of microbes. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2000, 54, 641–679.

- Abu-Taleb, A.M.F.; Abdelattef, R.S.; Abdel-Hady, A.A.; Omran, F.H.; El-korashi, L.A.; Abdel-aziz El-hady, H.; El-Gebaly, A.M. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori cagA and iceA Genes and Their Association with Gastrointestinal Diseases. Int. J. Microbiol. 2018, 2018, 4809093.

- Kamogawa-Schifter, Y.; Yamaoka, Y.; Uchida, T.; Beer, A.; Tribl, B.; Schöniger-Hekele, M.; Trauner, M.; Dolak, W. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori and its CagA subtypes in gastric cancer and duodenal ulcer at an Austrian tertiary referral center over 25 years. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0197695.

- Hatakeyama, M. Oncogenic mechanisms of the Helicobacter pylori CagA protein. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2004, 4, 688–694.

- Takahashi-Kanemitsu, A.; Knight, C.T.; Hatakeyama, M. Molecular anatomy and pathogenic actions of Helicobacter pylori CagA that underpin gastric carcinogenesis. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2020, 17, 50–63.

- Mimuro, H.; Suzuki, T.; Tanaka, J.; Asahi, M.; Haas, R.; Sasakawa, C. Grb2 Is a Key Mediator of Helicobacter pylori CagA Protein Activities. Mol. Cell 2002, 10, 745–755.

- Imai, S.; Ooki, T.; Murata-Kamiya, N.; Komura, D.; Tahmina, K.; Wu, W.; Takahashi-Kanemitsu, A.; Knight, C.T.; Kunita, A.; Suzuki, N.; et al. Helicobacter pylori CagA elicits BRCAness to induce genome instability that may underlie bacterial gastric carcinogenesis. Cell Host Microbe 2021, 29, 941–958.e910.

- Li, N.; Feng, Y.; Hu, Y.; He, C.; Xie, C.; Ouyang, Y.; Artim, S.C.; Huang, D.; Zhu, Y.; Luo, Z.; et al. Helicobacter pylori CagA promotes epithelial mesenchymal transition in gastric carcinogenesis via triggering oncogenic YAP pathway. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 37, 280.