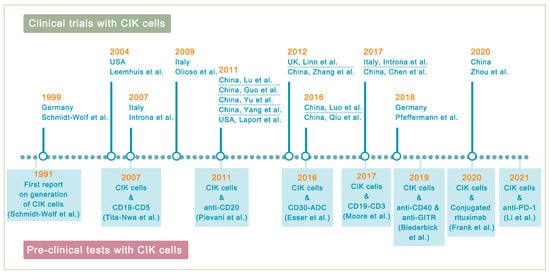

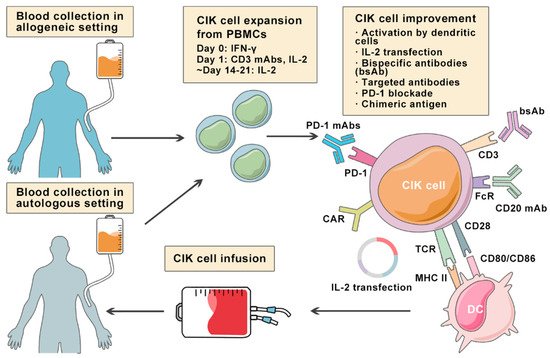

Lymphoma is a heterogeneous group of neoplasms including over 70 different subtypes. Its biological characteristic of deriving from lymphoid tissues makes it ideal for immunotherapy. Cytokine-induced killer (CIK) cells therapy is one of the adoptive immunotherapy which eliminates cancer cells by transfusing immune cells that have been expanded and activated in vitro. CIK cells are heterogeneous in nature and composed of CD3+CD56- (T cells), CD3-CD56+ (NK cells), and CD3+CD56+ (NKT cells) cell populations. The CD3+CD56+ subset is considered as the major effector cells that exert potent anti-tumor cytotoxicity in a major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-unrestricted manner. From 1991 to 2020, there are nearly 20 clinical trials conducted for the treatment of lymphoma. Moreover, a number of pre-clinical approaches are being investigated to improve CIK cell therapy to enhance its anti-tumor activity.

- lymphoma

- cytokine-induced killer cells

- adoptive cell transfer

- immunotherapy

1. Introduction

1. Background

2. Cytokine-Induced Killer Cells

| CIK Cells | CAR-T Cells | BiTEs | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manufacturing Process | PBMCs sequentially activated with 1000 IU/m IFN-γ on day 0, and 50 ng/mL anti-CD3 mAb and 600 IU/mL IL-2 on the following day; IL-2 supplemented every 2–3 days | T cells with CAR gene transduction primarily by lentiviruses; CARs consist of an scFv based ectodomain for antigen-binding, a transmembrane domain, and an endodomain containing TCR CD3ζ chain with or without costimulatory signaling components | Antibodies designed to bind to a selected TAA and CD3 on T cells simultaneously; produced in bioreactors by mammalian cell lines as secreted polypeptides | ||

| Effector Cells | CD3+CD56+ cells | Mostly αβ-TCR+ T cells | Endogenous CD8+ or CD4+ T cells | ||

| Cell Source | Autologous/allogeneic | Autologous/allogeneic | Autologous | ||

| Target Antigen | MIC A/B and ULBP1–4 | CD19, CD20, CD22, CD30, BCMA, etc. | CD19 | ||

| MHC Restriction | Dual-functional capability (non-MHC-restricted and TCR-mediated lysis) | TAA recognition by CARs is MHC-unrestricted | MHC-unrestricted | ||

| Mechanism | Release of perforin and granzyme B from CIK cells | Release of perforin and granzyme B from CAR-T cells | Activating T cells to release perforin and granzyme B by linking TAAs to CD3 on T cells | ||

| Toxicities and Side effects | Low-grade toxicities including fever, chills, fatigue, headache, and skin rash; grade 3 and 4 toxicities are rare; limited GVHD response in the allogeneic setting | CRS, ICANS, and MAS/HLH; potentially life-threatening | CRS and ICANS; severe toxicities are one of the major concerns | ||

| Clinical Efficacy | Varied due to heterogeneity of expension method and study design | Axicabtagene ciloleucel: 83% ORR, 58% CR; Tisagenlecleucel: 54% ORR, 40% CR; Lisocabtagene maraleucel: 73% ORR, 53% CR [13][14][15] | Axicabtagene ciloleucel: 83% ORR, 58% CR; Tisagenlecleucel: 54% ORR, 40% CR; Lisocabtagene maraleucel: 73% ORR, 53% CR [27,28,29] | Blinatumomab: 36% to 69% ORR in relapsed/refractory NHL [16][17] | Blinatumomab: 36% to 69% ORR in relapsed/refractory NHL [11,30] |

3. Improving CIK Cell Therapy on Lymphoma

Despite the positive clinical benefit observed in trials, it is difficult to achieve long-lasting response and complete cancer eradication in patients with refractory or relapsed lymphoma. Therefore, a number of pre-clinical approaches are being investigated to improve CIK cell therapy to enhance its anti-tumor activity (Figure 2). Among these innovative methods, bispecific antibodies (bsAb) represent a promising development bringing targeted antigen on tumor cells into close proximity to receptors on cytotoxic T-cells, and thereby triggering T-cell receptor signaling and anti-tumor immune response [18][53]. In a particular study, it was reported that the bsAb CD19 × CD5 (HD37 × T5.16) enhanced the cytotoxicity activity of CIK cells against B lymphoma cells [19][54]. Moore et al. used a bispecific antibody platform known as dual affinity retargeting (DART) to eradicate B-cell lymphomas by targeting the B-cell-specific antigen CD19 and the TCR/CD3 complex to effector T cells [20][55]. Subsequently, it was shown that CIK cells and CD19xCD3 DART can control and/or eradicate patient-derived tumor xenografts from chemo-refractory B-ALL and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) patients [21][56].