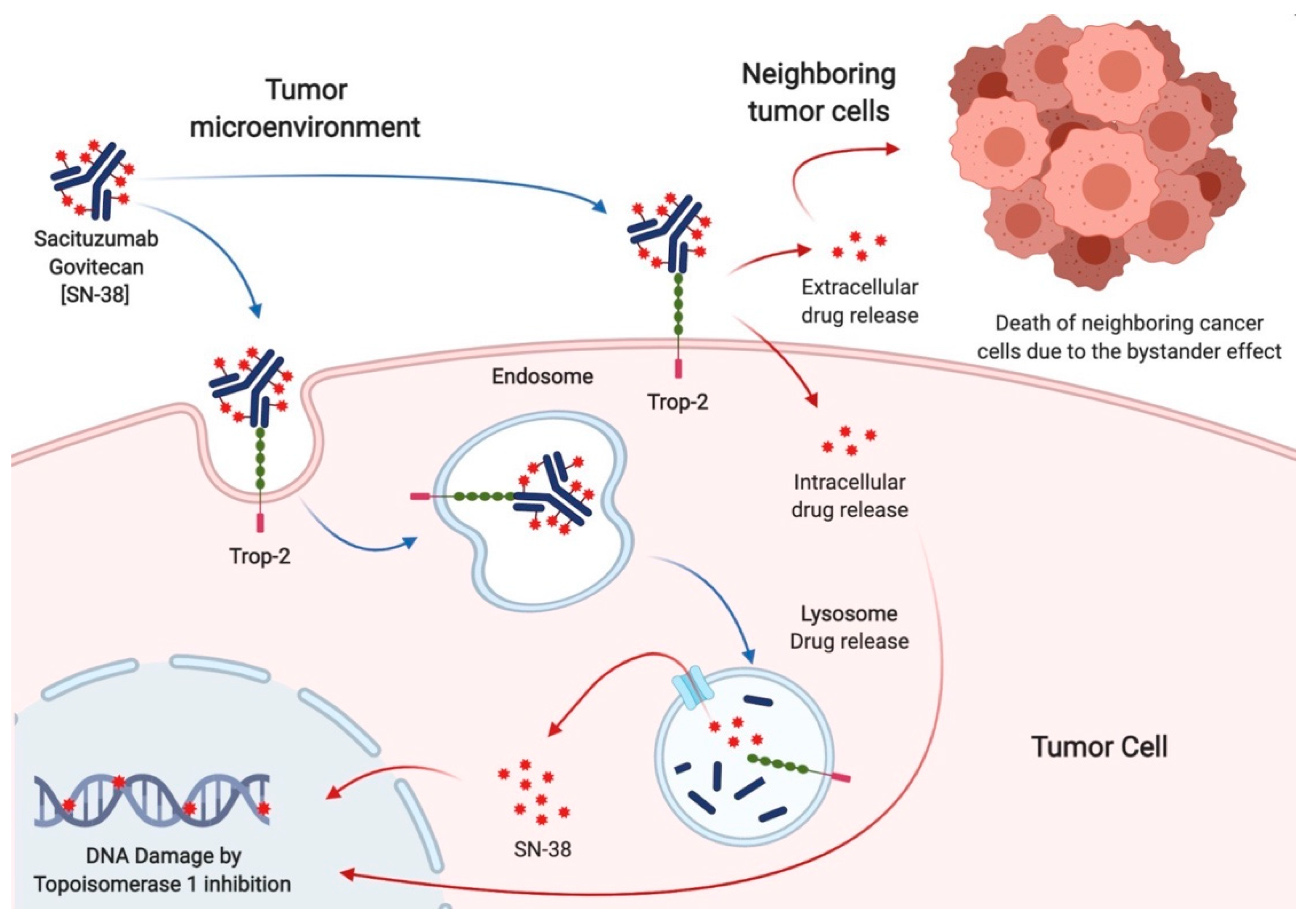

Sacituzumab govitecan (SG) is a third-generation antibody-drug conjugate, consisting of an anti-Trop-2 monoclonal antibody (hRS7), a hydrolyzable linker, and a cytotoxin (SN38), which inhibits topoisomerase 1. Specific pharmacological features, such as the high antibody to payload ratio, the ultra-toxic nature of SN38, and the capacity to kill surrounding tumor cells (the bystander effect), make SG a very promising drug for cancer treatment.

- antibody-drug conjugates

- Sacituzumab govitecan

- Trop-2

- breast cancer

1. Introduction

2. Sacituzumab Govitecan in Breast Cancer

Trial Name | Phase | Study Treatment | Study Population | (Number Enrolled If Available) | Study Design | Status | (Ref. If Published) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

NCT01631552 | I/II | SG | |||||||||||||||||||

Ongoing | |||||||||||||||||||||

Legend: BC: breast cancer; HER2-: HER2 negative; HR+: hormone receptor positive; m: metastatic; NACT: Neoadjuvant therapy; pCR: pathologic complete response; SG: Sacituzumab govitecan; TNBC: triple-negative breast cancer; wo: without.

3. Sacituzumab Govitecan in Other Solid Tumors

Table | Phase | Study Treatment | Study Population | (Number Enrolled If Available) | Study Design | Status | (Ref. If Published) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Solid Tumors | (515) | Open label, single group | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

NCT04617522 | 1 | Published |

SG | Advanced solid tumors and moderate liver impairment | [ |

Open label, non-randomized | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ongoing | NCT04039230 | I/II | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

NCT04724018 | 1 | SG + Talazoparib | SG + Enfortumab vedotin | mBC | Open label, single group | mUC after platinum and anti-PD1/L1 | Ongoing | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Open label, single group | Ongoing | NCT03424005 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

NCT03995706 | Ib/II | 1 | SG + Atezolizumab | SG | mTNBC | Breast cancer with brain metastases and glioblastoma | Open label, randomized multi-cohort | Ongoing | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Open label, single group | Ongoing | NCT03992131 | (SEASTAR) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

NCT01631552 | (IMMU-132-01) | Ib/II | 1/2 | SG + Rucaparib | SG | Advanced solid tumors | Epithelial cancers | Open label, non-randomized | Ongoing | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Open label, non-randomized | Published [27] | [22] |

NCT04927884 | Ib/II | SG | mTNBC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

NCT04826341 | 1/2 | SG + Berzosertib | Advanced solid tumors > 1 L | SCLC after platinum, | HRD cancers after PARPi | Open label, single group | Open label, non-randomized | Ongoing | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ongoing | NCT04647916 | II | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

NCT04863885 | SG | 1/2 | HER2-BC and brain metastases | Open label, single group | Ongoing | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

SG + IPI/NIVO | 1L cisplatin-ineligible mUC | Open label, non-randomized | Ongoing | NCT04468061 | (Saci-IO) | 2 | SG + Pembrolizumab | vs. Pembrolizumab | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

NCT03869190 | (MORPHEUS-UC) | 1/2 | mTNBC | SG + Atezolizumab | Open label, randomized | mUC | Ongoing | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Open label, randomized, multi-cohort | Ongoing | NCT04448886 | (Saci-IO HR+) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

NCT03992131 | 2 | (SEASTAR) | SG + Pembrolizumab | vs. Pembrolizumab | 1b/2 | HR+/HER2-mBC | SG + Rucaparib | Advanced or metastatic solid tumors | Open label, randomized | Open label, non-randomized | Ongoing | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ongoing | NCT04230109 (NeoSTAR) | 2 | SG + Pembrolizumab | vs. Pembrolizumab | Localized TNBC | Open label, randomized | Ongoing | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

NCT02574455 (ASCENT) | 3 | SG | vs. Chemotherapy | mTNBC | (529) | Open label, randomized | [26] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

NCT03337698 | (MORPHEUS-Lung) | 1b/2 | SG + Atezolizumab | mNSCLC | Open label, randomized | Ongoing | [27] |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

NCT03547973 | (TROPHY U-01) | 2 | SG | mUC after platinum or anti-PD1/L1 (113) | Open label, non-randomized | Published [25] | [30] |

NCT03901339 (TROPiCS-02) | 3 | SG | vs. Chemotherapy | HR + HER2-mBC | Open label, randomized | Ongoing | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

NCT04251416 | 2 | SG | Persistent/recurrent EC | Open label, single group assignment | Ongoing | NCT04595565 (SASCIA) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

NCT03964727 | (TROPiCS-03) | 3 | 2 | SG | vs. Chemotherapy | SG | HER2-/BC wo pCR after NACT | Open label, randomized | Metastatic solid tumors | Open label, single group assignment | Ongoing | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

NCT04559230 | 2 | SG | Recurrent glioblastoma | Open label, single group assignment | Ongoing | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

NCT03725761 | 2 | SG | Castration-resistant prostate cancer after second-generation ADT | Open label, single group assignment | Ongoing | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

NCT04527991 | (TROPiCS-04) | 3 | SG | vs. TAX/TXT/Vinflunine | Metastatic or locally advanced unresectable UC | Open label, randomized | Ongoing |

References

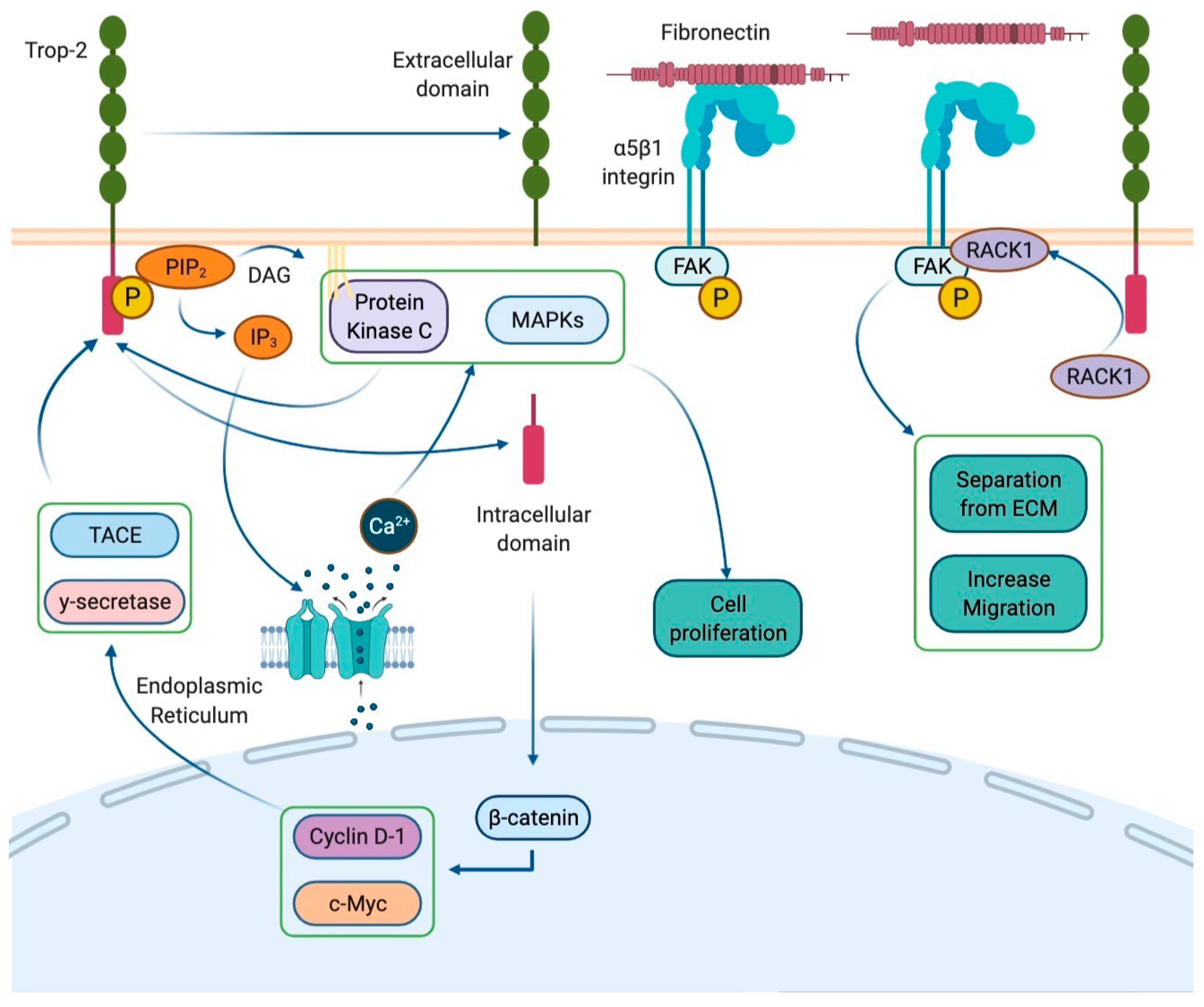

- Goldenberg, D.M.; Cardillo, T.M.; Govindan, S.V.; Rossi, E.A.; Sharkey, R.M. Trop-2 is a novel target for solid cancer therapy with sacituzumab govitecan (IMMU-132), an antibody–drug conjugate (ADC). Oncotarget 2015, 6, 22496–22512.

- Zhao, P.; Zhang, Z. TNF-alpha promotes colon cancer cell migration and invasion by upregulating TROP-2. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 15, 3820–3827.

- Trerotola, M.; Li, J.; Alberti, S.; Languino, L.R. Trop-2 inhibits prostate cancer cell adhesion to fibronectin through the beta1 integrin-RACK1 axis. J. Cell Physiol. 2012, 227, 3670–3677.

- Trerotola, M.; Jernigan, D.L.; Liu, Q.; Siddiqui, J.; Fatatis, A.; Languino, L.R. Trop-2 promotes prostate cancer metastasis by modulating beta(1) integrin functions. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 3155–3167.

- Kahounova, Z.; Remsik, J.; Fedr, R.; Bouchal, J.; Mickova, A.; Slabakova, E.; Bino, L.; Hampl, A.; Soucek, K. Slug-expressing mouse prostate epithelial cells have increased stem cell potential. Stem. Cell Res. 2020, 46, 101844.

- Zhao, W.; Jia, L.; Kuai, X.; Tang, Q.; Huang, X.; Yang, T.; Qiu, Z.; Zhu, J.; Huang, J.; Huang, W.; et al. The role and molecular mechanism of Trop2 induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition through mediated beta-catenin in gastric cancer. Cancer Med. 2019, 8, 1135–1147.

- Li, X.; Teng, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, X.; Xu, K.; Yao, H.; Yao, J.; Wang, H.; Liang, X.; et al. TROP2 promotes proliferation, migration and metastasis of gallbladder cancer cells by regulating PI3K/AKT pathway and inducing EMT. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 47052–47063.

- Guerra, E.; Trerotola, M.; Relli, V.; Lattanzio, R.; Tripaldi, R.; Vacca, G.; Ceci, M.; Boujnah, K.; Garbo, V.; Moschella, A.; et al. Trop-2 induces ADAM10-mediated cleavage of E-cadherin and drives EMT-less metastasis in colon cancer. Neoplasia 2021, 23, 898–911.

- Ohmachi, T.; Tanaka, F.; Mimori, K.; Inoue, H.; Yanaga, K.; Mori, M. Clinical significance of TROP2 expression in colorectal cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006, 12, 3057–3063.

- Fong, D.; Moser, P.; Krammel, C.; Gostner, J.M.; Margreiter, R.; Mitterer, M.; Gastl, G.; Spizzo, G. High expression of TROP2 correlates with poor prognosis in pancreatic cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2008, 99, 1290–1295.

- Hou, J.; Lv, A.; Deng, Q.; Zhang, G.; Hu, X.; Cui, H. TROP2 promotes the proliferation and metastasis of glioblastoma cells by activating the JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway. Oncol. Rep. 2019, 41, 753–764.

- Zeng, P.; Chen, M.B.; Zhou, L.N.; Tang, M.; Liu, C.Y.; Lu, P.H. Impact of TROP2 expression on prognosis in solid tumors: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 33658.

- Zhao, W.; Kuai, X.; Zhou, X.; Jia, L.; Wang, J.; Yang, X.; Tian, Z.; Wang, X.; Lv, Q.; Wang, B.; et al. Trop2 is a potential biomarker for the promotion of EMT in human breast cancer. Oncol. Rep. 2018, 40, 759–766.

- Cardillo, T.M.; Govindan, S.V.; Sharkey, R.M.; Trisal, P.; Goldenberg, D.M. Humanized anti-Trop-2 IgG-SN-38 conjugate for effective treatment of diverse epithelial cancers: Preclinical studies in human cancer xenograft models and monkeys. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 17, 3157–3169.

- Strop, P.; Tran, T.T.; Dorywalska, M.; Delaria, K.; Dushin, R.; Wong, O.K.; Ho, W.H.; Zhou, D.; Wu, A.; Kraynov, E.; et al. RN927C, a Site-Specific Trop-2 Antibody-Drug Conjugate (ADC) with Enhanced Stability, Is Highly Efficacious in Preclinical Solid Tumor Models. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2016, 15, 2698–2708.

- Sharkey, R.M.; McBride, W.J.; Cardillo, T.M.; Govindan, S.V.; Wang, Y.; Rossi, E.A.; Chang, C.H.; Goldenberg, D.M. Enhanced Delivery of SN-38 to Human Tumor Xenografts with an Anti-Trop-2-SN-38 Antibody Conjugate (Sacituzumab Govitecan). Mol. Cancer Ther. 2016, 15, 2698–2708.

- Cardillo, T.M.; Govindan, S.V.; Sharkey, R.M.; Trisal, P.; Arrojo, R.; Liu, D.; Rossi, E.A.; Chang, C.H.; Goldenberg, D.M. Sacituzumab Govitecan (IMMU-132), an Anti-Trop-2/SN-38 Antibody-Drug Conjugate: Characterization and Efficacy in Pancreatic, Gastric, and Other Cancers. Bioconjug. Chem. 2015, 26, 919–931.

- Shaffer, C. Trop2 deal heats up antibody-drug conjugate space in cancer. Nat. Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 128–130.

- Goldenberg, D.M.; Sharkey, R.M. Sacituzumab govitecan, a novel, third-generation, antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) for cancer therapy. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2020, 20, 871–885.

- Hafeez, U.; Parakh, S.; Gan, H.K.; Scott, A.M. Antibody-Drug Conjugates for Cancer Therapy. Molecules 2020, 25, 4764.

- Wahby, S.; Fashoyin-Aje, L.; Osgood, C.L.; Cheng, J.; Fiero, M.H.; Zhang, L.; Tang, S.; Hamed, S.S.; Song, P.; Charlab, R.; et al. FDA Approval Summary: Accelerated Approval of Sacituzumab Govitecan-hziy for Third-line Treatment of Metastatic Triple-negative Breast Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 1850–1854.

- Ocean, A.J.; Starodub, A.N.; Bardia, A.; Vahdat, L.T.; Isakoff, S.J.; Guarino, M.; Messersmith, W.A.; Picozzi, V.J.; Mayer, I.A.; Wegener, W.A.; et al. Sacituzumab govitecan (IMMU-132), an anti-Trop-2-SN-38 antibody-drug conjugate for the treatment of diverse epithelial cancers: Safety and pharmacokinetics. Cancer 2017, 123, 3843–3854.

- Starodub, A.N.; Ocean, A.J.; Shah, M.A.; Guarino, M.J.; Picozzi, V.J., Jr.; Vahdat, L.T.; Thomas, S.S.; Govindan, S.V.; Maliakal, P.P.; Wegener, W.A.; et al. First-in-Human Trial of a Novel Anti-Trop-2 Antibody-SN-38 Conjugate, Sacituzumab Govitecan, for the Treatment of Diverse Metastatic Solid Tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 3870–3878.

- Bardia, A.; Mayer, I.A.; Diamond, J.R.; Moroose, R.L.; Isakoff, S.J.; Starodub, A.N.; Shah, N.C.; O’Shaughnessy, J.; Kalinsky, K.; Guarino, M.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Anti-Trop-2 Antibody Drug Conjugate Sacituzumab Govitecan (IMMU-132) in Heavily Pretreated Patients With Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 2141–2148.

- Bardia, A.; Mayer, I.A.; Vahdat, L.T.; Tolaney, S.M.; Isakoff, S.J.; Diamond, J.R.; O’Shaughnessy, J.; Moroose, R.L.; Santin, A.D.; Abramson, V.G.; et al. Sacituzumab Govitecan-hziy in Refractory Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 741–751.

- Bardia, A.; Hurvitz, S.A.; Tolaney, S.M.; Loirat, D.; Punie, K.; Oliveira, M.; Brufsky, A.; Sardesai, S.D.; Kalinsky, K.; Zelnak, A.B.; et al. Sacituzumab Govitecan in Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1529–1541.

- Kalinsky, K.; Diamond, J.R.; Vahdat, L.T.; Tolaney, S.M.; Juric, D.; O’Shaughnessy, J.; Moroose, R.L.; Mayer, I.A.; Abramson, V.G.; Goldenberg, D.M.; et al. Sacituzumab govitecan in previously treated hormone receptor-positive/HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer: Final results from a phase I/II, single-arm, basket trial. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 1709–1718.

- Rugo, H.S.; Bardia, A.; Tolaney, S.M.; Arteaga, C.; Cortes, J.; Sohn, J.; Marme, F.; Hong, Q.; Delaney, R.J.; Hafeez, A.; et al. TROPiCS-02: A Phase III study investigating sacituzumab govitecan in the treatment of HR+/HER2- metastatic breast cancer. Future Oncol. 2020, 16, 705–715.

- Zaman, S.; Jadid, H.; Denson, A.C.; Gray, J.E. Targeting Trop-2 in solid tumors: Future prospects. Onco. Targets Ther. 2019, 12, 1781–1790.

- Tagawa, S.T.; Balar, A.V.; Petrylak, D.P.; Kalebasty, A.R.; Loriot, Y.; Flechon, A.; Jain, R.K.; Agarwal, N.; Bupathi, M.; Barthelemy, P.; et al. TROPHY-U-01: A Phase II Open-Label Study of Sacituzumab Govitecan in Patients With Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma Progressing After Platinum-Based Chemotherapy and Checkpoint Inhibitors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 2474–2485.

- Perrone, E.; Manara, P.; Lopez, S.; Bellone, S.; Bonazzoli, E.; Manzano, A.; Zammataro, L.; Bianchi, A.; Zeybek, B.; Buza, N.; et al. Sacituzumab govitecan, an antibody-drug conjugate targeting trophoblast cell-surface antigen 2, shows cytotoxic activity against poorly differentiated endometrial adenocarcinomas in vitro and in vivo. Mol. Oncol. 2020, 14, 645–656.

- Zeybek, B.; Manzano, A.; Bianchi, A.; Bonazzoli, E.; Bellone, S.; Buza, N.; Hui, P.; Lopez, S.; Perrone, E.; Manara, P.; et al. Cervical carcinomas that overexpress human trophoblast cell-surface marker (Trop-2) are highly sensitive to the antibody-drug conjugate Sacituzumab Govitecan. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 973.

- Han, C.; Bellone, S.; Schwartz, P.E.; Govindan, S.V.; Sharkey, R.M.; Goldenberg, D.M.; Santin, A.D. Sacituzumab Govitecan (IMMU-132) in treatment-resistant uterine serous carcinoma: A case report. Gynecol. Oncol. Rep. 2018, 25, 37–40.

- Wolber, P.; Nachtsheim, L.; Hoffmann, F.; Klussmann, J.P.; Meyer, M.; von Eggeling, F.; Guntinas-Lichius, O.; Quaas, A.; Arolt, C. Trophoblast Cell Surface Antigen 2 (Trop-2) Protein is Highly Expressed in Salivary Gland Carcinomas and Represents a Potential Therapeutic Target. Head Neck Pathol. 2021.