Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Mingqing Li and Version 2 by Rita Xu.

Endometriosis is a condition that is influenced by hormones and involves stroma and glands being found outside the uterus; there are increases in proliferation, invasion, internal bleeding, and fibrosis.

- matrix metalloproteinases

- endometriosis

- function

1. Introduction

Endometriosis is a benign, hormone-dependent disease characterized by the presence of endometrial glands and stroma outside the uterus and affects at least 10–15% of women of reproductive age [1]. Several characteristics, such as infertility, dysmenorrhea, and dyspareunia, are associated with endometriosis [2]. Moreover, estrogen, matrix remodeling, inflammation, and oxidative stress have been shown to be involved in endometriosis progression from early to advanced stages [3].

Based on the hypothesis of the retrograde transplantation theory proposed by Sampson in 1927, we recognize the significance of matrix regrading and matrix remolding. Endometriosis is established when endometrial cells (influenced by hormone fluctuations) break off and travel via the fallopian tubes to new sites, where they implant and grow. The extracellular matrix (ECM) is a complex network of macromolecular structures, such as collagens, proteoglycans, glycoproteins, and elastin [4]. The matrix metalloprotease (MMP) family is devoted to maintaining ECM homeostasis, and the dysregulation of its expression leads to the disease. Since the 1960s, the MMP family has drawn much attention, and its functions have been further determined [5] and systematically reviewed. [6].

2. The MMP Family

MMPs belong to a large family of calcium-dependent, zinc-containing endopeptidases that are known for their ability to cleave nonmatrix proteins, as well as several ECM constituents (e.g., collagens, proteoglycan, and glycoproteins). In 1949, MMPs were discovered to be depolymerizing enzymes that could promote the proliferation of malignant cells by remolding connective tissue stroma such as blood vessels [7]. A decade later, the first vertebrate MMP was isolated and identified to act as a collagenase [5]. At least 28 MMPs have been identified in mammals to date [8].

2.1. Classification of MMPs

How MMPs should be classified remains controversial. A previous report classified them into the following five groups based on their substrate-specificity and location: collagenases, gelatinases, stromelysins, matrilysins, and membrane-type metalloproteinases [9]. However, Garcia-Fernandez et al. and Kapoor et al. both divided MMPs into six groups depending on their different substrates. Compared with the previous five groups, the latter researchers added an “other MMPs” group, which included those that did not fit into any other category [7][10][7,10]. Beyond that, MMPs can also be divided into two groups: secreted MMPs and anchor MMPs. Of the known MMPs, MMP14, 15, 16, 17, 23, 24, and 25 are membrane-anchored [11][12][11,12].

2.2. Structure of MMPs

The sophisticated structure of MMPs has been known for some time and has been described in significant detail [13]. The compositions of most MMPs are the same: they involve a pro-peptide domain, a signal peptide, a cysteine switch motif, a catalytic domain, and a hemopexin-like domain [7]. However, some MMPs have different structural characteristics that enable them to perform special activities. For example, MMP2 and MMP9 can interact with collagen via three fibronectin type-II domains. Moreover, MMP7, MMP23, and MMP26 have no C-terminal hemopexin-like domain, which usually consists of 190 amino acids. Additionally, MMP23 is the only MMP that possesses a cysteine-rich and Ig domain. Some researchers have designed MMP inhibitors according to the specific structures. Ilomastat (GM-6001), a first-generation collagen peptidomimetic, is a broad-spectrum MMP inhibitor [14][15][14,15]. However, due to its poor bioavailability, clinical trials of ilomastat have failed. However, Tanomastat (BAY 12-9566) has been shown to potently and selectively inhibit MMP13, gelatinase A, and gelatinase B. It is an analog of biphenyl non-peptide butanoic acid and was first developed by Bayer, Inc. (Leverkusen, Germany) [16]. However, no anti-MMP inhibitors with few side effects and strong specificity have been used in clinical anti-tumor therapy to date.

2.3. The Expression of MMPs (Natural MMP Inhibitors)

MMPs are generally poorly expressed in humans due to their specific endogenous inhibitors, known as the tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase (TIMP) family, which includes four known proteins: TIMP-1, 2, 3, and 4 [17]. TIMPs can bind to the catalytic domains of MMPs with a 1:1 stoichiometric ratio and then block their enzymatic activity [18][19][18,19]. The TIMP family includes proteins with specific substrates; for example, TIMP-1 can only regulate the membrane-type MMPs, but the other three members have wider ranges of biological activity [9]. In addition to MMPs, TIMPs can suppress other enzymes, such as those of the disintegrin and metalloproteinase (ADAM) family [20][21][22][20,21,22].

3. MMP Expression in Endometriosis

3.1. Summary of Clinical Studies

Aside from MMP7, which is only expressed in epithelial endometrial cells, MMPs are present in both the stromal and epithelial tissue compartments of the endometrium [23]. As an invasive disorder, endometriosis involves increased MMP activity. Several studies have reported that the levels of MMPs are elevated in the ectopic tissue, peritoneal fluid, or sera of patients with endometriosis, especially MMP2 and MMP9 [24][25][26][24,25,26]. In addition, Borghese et al. shared gene expression profiles of eutopic. vs. ectopic endometrium in 2008 and provided a list of more than 5600 genes related to endometriosis. The overexpressed extracellular matrix genes (such as MMP23 and MMP26) showed significant expression differences [27]. However, the potential mechanism of the dysregulation of MMP23 and MMP26 expression still needs further research. Considering their key roles in endometriosis, MMPs have been considered potential therapeutic targets for this disease. As presented in Table 1, accumulating evidence has demonstrated that MMPs play significant roles in promoting the development of endometriosis.

Table 1. Changes in MMPs in endometriosis.

| Classification | MMPs | Location | Change (Endometriosis. vs. Control) | Reference | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collagenases | MMP1 | Eutopic endometrium Peripheral blood |

up down |

[28] [29] |

|||||||

| MMP13 | Ectopic endometrium Peritoneal fluid |

up down |

[30] [31] |

||||||||

| Gelatinases | MMP2 | Ectopic endometrium Eutopic endometrium Peripheral blood Peritoneal fluid |

up up down ns up up |

[24][32][33][34][35] [36] [37] [25][34] [24][38] | [24,32 | [38] [ | ,33 | 24 | ,34,35] [36] [37] [25,34] [24,38 | ] | ] [24,38] |

| MMP9 | Ectopic endometrium Eutopic endometrium Peripheral blood |

up ns down up |

[32][33][39] [25] [28] | [32 | [ | ,33 | 40 | ,39 | ] | ] [25] [28] [40] |

|

| Stromelysins | MMP3 | Ectopic endometrium Eutopic endometrium Peripheral blood |

up down ns |

[34][35][41][42] [34] [29] | [34,35,41,42] [34] [29] |

||||||

| MMP10 | Ectopic endometrium | up | [35] | ||||||||

| MMP11 | Ectopic endometrium Eutopic endometrium |

up down |

[43][44] [34] | [43,44] [34] |

|||||||

| Matrilysins | MMP7 | Ectopic endometrium Peripheral blood |

up up |

[43][45][46] [45] | [43,45,46] [45] |

||||||

| MMP26 | Ectopic endometrium | up | [27] | ||||||||

| Membrane-type MMPs | MT1-MMP | Ectopic endometrium Eutopic endometrium Peritoneal fluid |

up up down |

[33][37] [36] [31] | [33,37] [36] [31] |

||||||

| MT5-MMP | Eutopic endometrium | up | [47] | ||||||||

| Other MMPs | MMP12 | Ectopic endometrium | up | [30] | |||||||

| MMP23 | Ectopic endometrium | up | [27] |

MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; ns, no significant difference.

3.2. Complexity of MMP Regulation in Endometriosis

Over the past few years, evidence has shown that MMPs play an important role in the mechanisms involved in the occurrence and treatment of endometriosis. The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-MMP7 signaling pathway has been shown to be involved in the regulation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) during the progression of endometriosis [45]. Moreover, chloride channel-3 (CIC3) and stress-induced phosphoprotein 1 enhance the activity of MMP9, while microRNA-33b has the opposite effect [48][49][50][48,49,50]. The fibrinogen alpha chain is upregulated and affects MMP2 in endometriosis [51]. Moreover, it has been shown that leptin promotes cell migration and invasion and that the cyclooxygenase-prostaglandin E2 (PGE2)-pAKT axis can promote angiogenesis via MMP2 [37][52][37,52]. In an in vivo trial, Shu et al. observed that the silencing of aquaporin 1, a water-channel protein, could influence the expression of invasion-related factors (MMP2, MMP9, TIMP1, and TIMP2), alleviating the progression of endometriosis in a mouse model [53]. Lipoxin A4 (LXA4) is a lipid medium that is widely involved in the establishment of endometriosis [54][55][54,55]. Moreover, LAX4 can suppress estrogen-mediated EMT via binding to its receptor and can inhibit the activities of MMP2 and MMP9 [56].

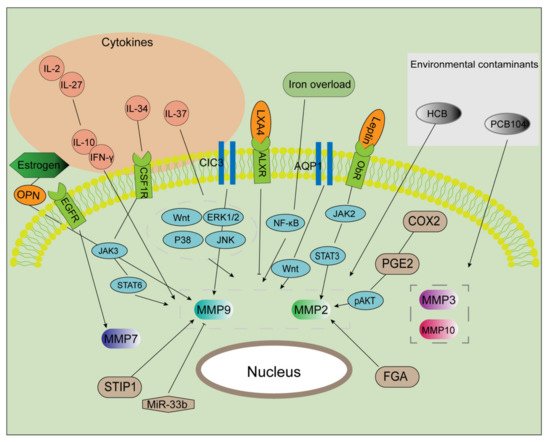

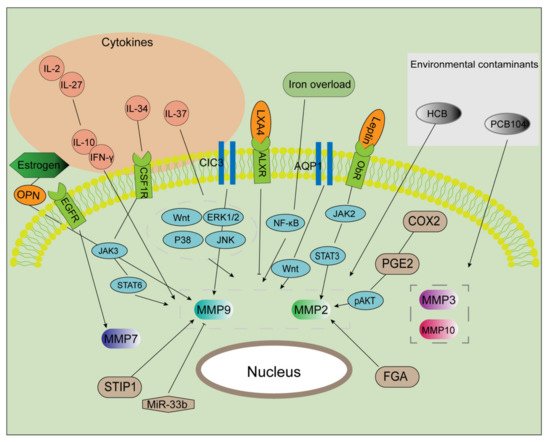

It is well known that the microenvironment of patients with endometriosis is inflammatory. Interleukin (IL)-2 and IL-27 synergistically inhibit MMP9 expression by maintaining the balance of interferon (IFN)-γ and IL-10, thereby improving the invasive ability of endometriosis cells [57]. Lin et al. reported that IL-34, through activating signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 (STAT6), promoted the expression of MMP9 in endometriosis in vitro and in vivo via the colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor/Janus kinase 3/STAT6 pathway [58]. Moreover, IL-37 affects downstream MMP9 expression via a variety of signaling pathways and regulates the biological behavior of endometrial stromal cells [59]. MMP2 and MMP9 can be regarded as the most typical downstream biomarkers in the progression of endometriosis. Furthermore, as shown in Figure 1, various extracellular factors, such as estrogen [60], cytokines [57][58][59][57,58,59], iron overload [61], and environmental contaminants [62][63][62,63], contribute to the regulation of MMPs expression.

Figure 1. Multiple factors regulate MMP activities. After exposure to certain environmental contaminants (e.g., PCB104 and HCB), the expression of MMPs (MMP3, 10, 2, and 9) is markedly enhanced. IL-37 upregulates the expression of MMPs via multiple signaling pathways. IL-2 and IL-27 were found to maintain the balance of IL-10 and IFN-γ, promoting MMP2 and MMP9 expression and then inducing cell invasion and proliferation. IL-34 binds to CSF1R, which activated the JAK/STAT6 pathway in an autocrine manner. Estrogen induces MMP9 expression via the OPN. CIC3 and STIR1 improve the activity of MMP9, while miR-33b inhibits it. AQP1 promotes the expression of MMP2 and 9 via the Wnt signaling pathway. The COX2/PGE2/pAKT axis, as well as the leptin/JAK2/STAT3 axis, serves as a significant regulator in increasing MMP2 expression. Additionally, MMP2 is a target of FGA and LXA4. MMP7 is a downstream component in the EGFR-mediated signaling pathway. Iron markedly increases EMT and MMP2/9 activities in endometriosis.

MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; PCB104, polychlorinated biphenyl 104; HCB, hexachlorobenzene; CSF1R, colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor; OPN, osteopontin; CIC3, chloride channel-3; STIR1, stress-induced phosphoprotein 1; miR, microRNA; AQP1, aquaporin 1; FGA, fibrinogen alpha chain; COX2, cyclooxygenase 2; PGE2, prostaglandin E2; p, phosphorylated; JAK2, Janus kinase 2; STAT3, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; LXA4, lipoxin A4; EMT, epithelial-mesenchymal transition.