Tumours may develop from stem cells as well as differentiated cells able to divide. Phenotypically, the two principal types of cell of origin convert with the degree of genetic changes as the stem cell derived tumours stop earlier in the differentiation and the differentiated cells gradually lose specific traits. However, the growth regulation of the cell of origin, which depends on its receptors conveying signals influencing proliferation, is essential in tumourigenesis since every cell division carries a small risk of mutation. Moreover, some normal cells have properties making them prone to develop into tumours as neuroendocrine cells which display low adherence as they occur spread by other cells, and also because they release signal substances affecting the vascular bed (for instance histamine).. Therefore, these cells may be the origin of tumours more malignant than apparent from their phenotype. Knowledge of the receptors of the cell of origin gives increased possibility to understand the tumourigenesis and also improvement of prophylaxis and treatment of the tumours. Finally, spread of nearly normal tumour cells at an early phase gives a plausible explanation of quiescent tumor cell/dormant tumours.

- Carcinogenesis

- cell of origin

- dormancy

- ECL cell

- gastrin

- gastric cancer

- hormones

1. Introduction

Among the hallmarks of cancer are the ability to invade other tissues, to metastasize to other organs not in direct continuity with the tumor and not obey normal regulation of proliferation. These properties are due to genetic changes in the cancer cells, most often due to mutations. Only cells able to divide can give rise to neoplasia. Benign tumors develop when the number set point of a cell type is increased. With time, new mutations occur, and the tumor cell is gradually transformed into a more malignant one. Thus, benign tumors imply an increased risk of developing into cancer. Most often, in cancer cells there are an accumulation of mutations, but sometimes a mutation affecting a key gene results in a cancer cell with few mutations. In this review I will focus on the cell of origin of tumors, particularly that differentiated cells are able to divide and that not only stem cells may develop into tumors. Moreover, since each cell division by chance implies a small risk of mutation, every stimulation of proliferation is accompanied by an increased mutation risk. Knowledge of the regulation of proliferation of the cell of origin will therefore indicate the mechanism of the tumorigenesis. Furthermore, signal molecules including hormones (estrogen, testosterone, gastrin) thus become important in tumorigenesis. Finally, understanding that differentiated cells with slow proliferation may also explain the phenomenon of so-called dormant tumor cells.

2. Cell of Origin

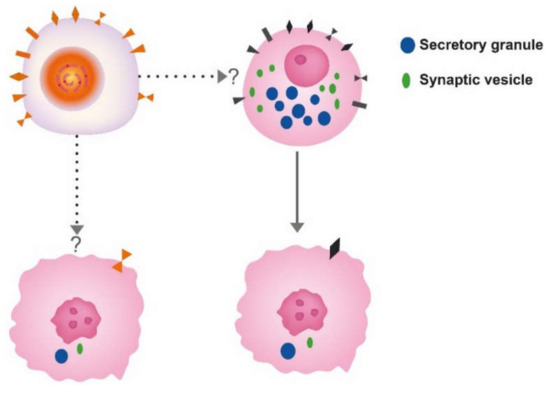

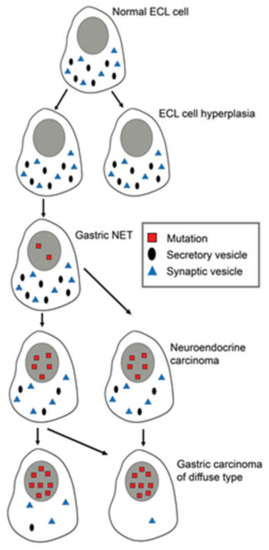

Correct identification of the cell of origin is of the utmost importance in oncology. The prevailing theory has been that tumors develop from stem cells based upon similarities between stem cells and cancer cells . In benign tumors, the maturation stops late, leading to a tumor phenotype close to the normal tissue, whereas in malignant tumors, the maturation stops early, leading to tumors where the cellular origin may be difficult to recognize (). Another view is that tumours may develop from any cell able to divide. With accumulation of mutations the differentiated cells gradually lose specific traits (secretory granules, synaptic markers, receptors) leading to cells increasingly different from the cell of origin ( Figure 1 and Figure 2)

Figure 1. The different theories for the cell of origin of cancers; the stem cell upper left and differentiated cell, here depicted as a neuroendocrine cell to the right. Whether neuroendocrine cells in the gastrointestinal tract develop from the stem cell or separate neuroendocrine precursors is still debated. Anyhow, both cells may convert into cancer cells of similar phenotype.

Figure 2. Changes in differentiated ECL cells during tumorigenesis/carcinogenesis with accumulation of mutations, leading to loss of specific markers, making it increasingly difficult to recognize the cell of origin. Reproduced with permission from Waldum HL, Brenna E, Sandvik AK 1998.[1]

Why is it so important to correctly identify the cell of origin? If the tumors develop from a differentiated cell, the growth regulation of this cell type becomes essential in tumorigenesis, and vice versa—if the tumors originate from the stem cell, its regulation becomes crucial. Thus, the receptors related to proliferation on the cell of origin will give an indication of the tumorigenesis. Our experience with the role of gastrin and the ECL cell in gastric tumorigenesis exemplifies tumourigenesis from a differentiated cell of origin.Thus, gastrin stimulates the proliferation of its target cell, the enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cell,which via hyperplasia develops into the relatively benign neuroendocrine tumour (NET) to neuroendocrine carcinoma and further to adenocarcinoma with neuroendocrine differentiation [2][3]. Hypergastrinemia irrespective of cause and in all species adequately examined induces such a development. Therefore, long-term iatrogenic hypergastrinemia by profound acid inhibition should be avoided [4], particularly in patients with Helicobacter pylori gastritis since hypergastrinemia may be the cause of gastric cancer also in Helicobacter pylori gastritis [5]

References

- Relationship of ECL cells and gastric neoplasia . Yale J Biol Med . May-Aug 1998;71(3-4):325-35.. Retrieved 2020-8-18

- The Enterochromaffin-like [ECL] Cell-Central in Gastric Physiology and Pathology . Int J Mol Sci . 2019 May 17;20(10):2444. doi: 10.3390/ijms20102444.. Retrieved 2020-8-18

- Signet ring cells in gastric carcinomas are derived from neuroendocrine cells . J Histochem Cytochem . 2006 Jun;54(6):615-21. doi: 10.1369/jhc.5A6806.2005. Epub 2005 Dec 12.. Retrieved 2020-8-18

- Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) may cause gastric cancer - clinical consequences . Scand J Gastroenterol . 2018 Jun;53(6):639-642. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2018.1450442. Epub 2018 May 31.. Retrieved 2020-8-18

- Gastrin May Mediate the Carcinogenic Effect of Helicobacter pylori Infection of the Stomach . Dig Dis Sci . 2015 Jun;60(6):1522-7. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3468-9. Epub 2014 Dec 6.. Retrieved 2020-8-18