Intraoperative Guidance Using Hyperspectral Imaging: A Review for Surgeons

1

Institute for Research against Digestive Cancer (IRCAD), 67091 Strasbourg, France

2

General Surgery Department, Ospedale Card. G. Panico, 73039 Tricase, Italy

3

Department of Visceral Surgery and Medicine, Inselspital, Bern University Hospital, University of Bern, 3008 Bern, Switzerland

4

Department for BioMedical Research, Visceral Surgery and Medicine, University of Bern, 3008 Bern, Switzerland

5

Department of General Surgery, St. Georg Hospital, 04129 Leipzig, Germany

6

ICube Laboratory, Photonics Instrumentation for Health, University of Strasbourg, 67400 Strasbourg, France

*

Author to whom correspondence should be addressed.

Academic Editor: Sang Hwan Nam

Received: 6 October 2021 / Revised: 3 November 2021 / Accepted: 5 November 2021 / Published: 8 November 2021

1

Institute for Research against Digestive Cancer (IRCAD), 67091 Strasbourg, France

2

General Surgery Department, Ospedale Card. G. Panico, 73039 Tricase, Italy

3

Department of Visceral Surgery and Medicine, Inselspital, Bern University Hospital, University of Bern, 3008 Bern, Switzerland

4

Department for BioMedical Research, Visceral Surgery and Medicine, University of Bern, 3008 Bern, Switzerland

5

Department of General Surgery, St. Georg Hospital, 04129 Leipzig, Germany

6

ICube Laboratory, Photonics Instrumentation for Health, University of Strasbourg, 67400 Strasbourg, France

*

Author to whom correspondence should be addressed.

Academic Editor: Sang Hwan Nam

Received: 6 October 2021 / Revised: 3 November 2021 / Accepted: 5 November 2021 / Published: 8 November 2021

1

Institute for Research against Digestive Cancer (IRCAD), 67091 Strasbourg, France

2

General Surgery Department, Ospedale Card. G. Panico, 73039 Tricase, Italy

3

Department of Visceral Surgery and Medicine, Inselspital, Bern University Hospital, University of Bern, 3008 Bern, Switzerland

4

Department for BioMedical Research, Visceral Surgery and Medicine, University of Bern, 3008 Bern, Switzerland

5

Department of General Surgery, St. Georg Hospital, 04129 Leipzig, Germany

6

ICube Laboratory, Photonics Instrumentation for Health, University of Strasbourg, 67400 Strasbourg, France

*

Author to whom correspondence should be addressed.

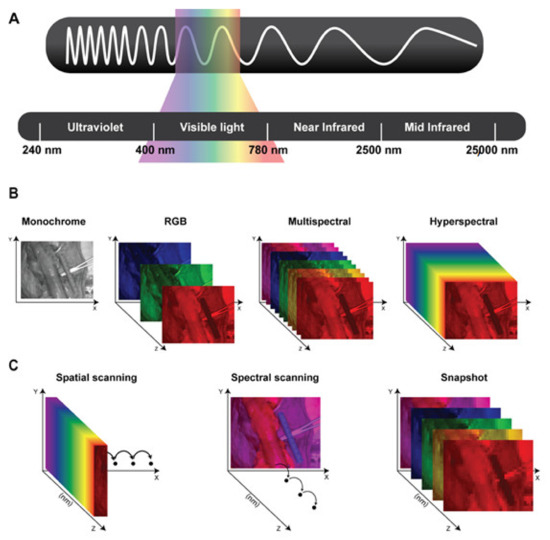

Hyperspectral imaging (HSI) is a novel optical imaging modality, which has recently found diverse applications in the medical field. HSI is a hybrid imaging modality, combining a digital photographic camera with a spectrographic unit, and it allows for a contactless and non-destructive biochemical analysis of living tissue. HSI provides quantitative and qualitative information of the tissue composition at molecular level in a contrast-free manner, hence making it possible to objectively discriminate between different tissue types and between healthy and pathological tissue. Over the last two decades, HSI has been increasingly used in the medical field, and only recently it has found an application in the operating room. In the last few years, several research groups have used this imaging modality as an intraoperative guidance tool within different surgical disciplines. Despite its great potential, HSI still remains far from being routinely used in the daily surgical practice, since it is still largely unknown to most of the surgical community. The aim of this study is to provide clinical surgeons with an overview of the capabilities, current limitations, and future directions of HSI for intraoperative guidance.

Keywords: hyperspectral imaging; optical imaging; image-guided surgery; intraoperative guidance; intraoperative imaging; precision surgery