You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Peter Tang and Version 1 by François Aubin.

The epidermis is a living, multilayered barrier with five functional levels, including a physical, a chemical, a microbial, a neuronal, and an immune level.

- epidermis

- skin barrier

- stratum corneum

- ceramides

- keratinization

- desmosomes

- tight junctions

- immunity

- sensory nerves

- microbiome

1. Physical Protection

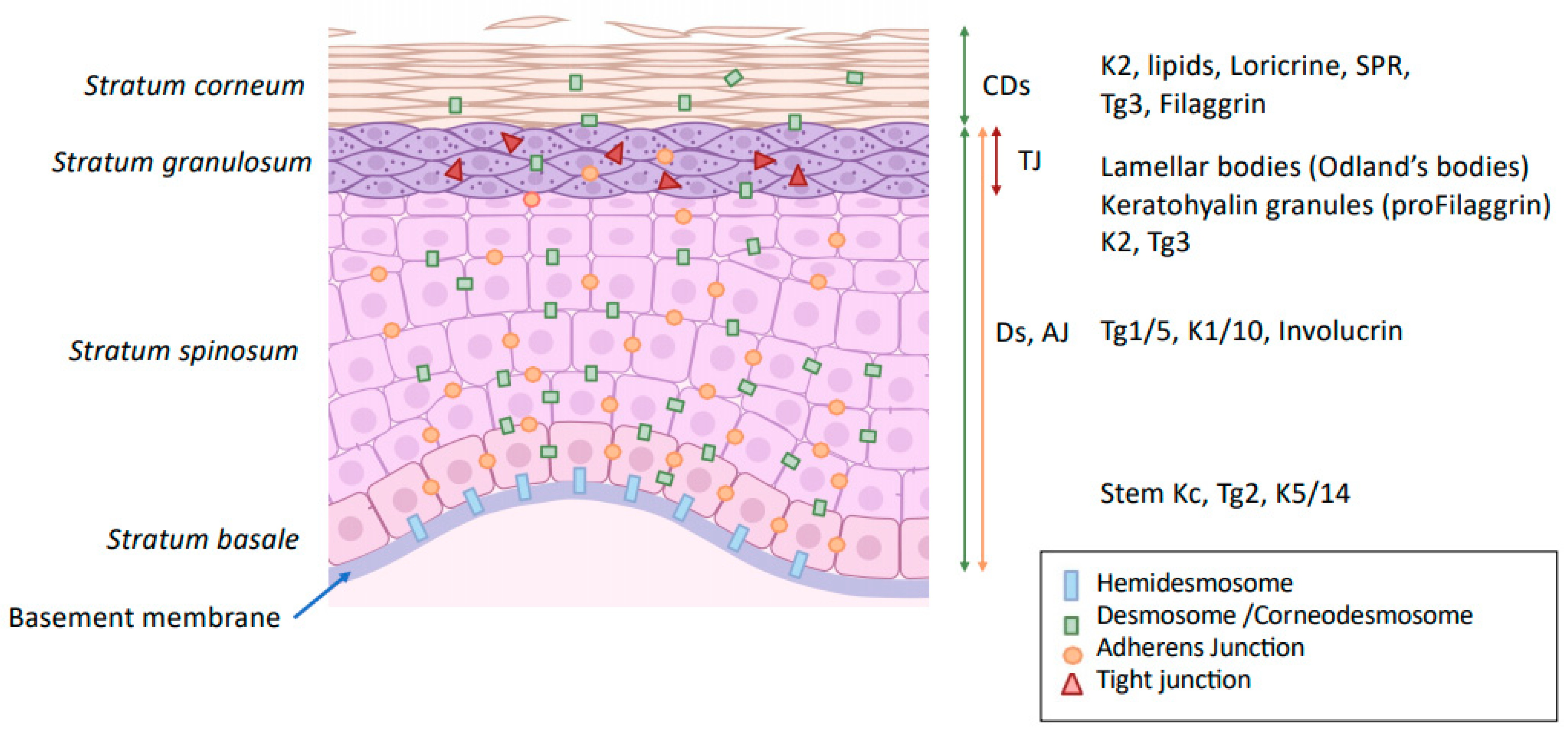

The epidermis is characterized by a highly cohesive, multilayered cell architecture. Living cell layers of the epidermis are crucial in the formation and maintenance of the barrier on two different levels. First, keratinocytes form the outermost protective, dead layer of the skin—the cornified or horny layer (stratum corneum, SC), through a complex terminal differentiation process named keratinization. Second, the living cell layers form a resilient tissue by providing mechanical cohesion between cells by means of desmosomes, adherens junctions (AJ), and tight junctions (TJ) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Modification of intercellular junction along keratinocyte differentiation. Kc: keratinocytes Ds: desmosome; CDs: corneodesmosome; TJ: tight junction; AJ: adherens junction; K: keratin; Tg: transglutaminase; SPR: small proline-rich proteins.

2. Chemical Aspect of the Epidermal Barrier

The chemical factors included in the SC contribute to its acidic pH and to the antimicrobial activity through the release of anti-microbial peptides (AMP).

The pH of normal human SC ranges from 4.5 to 5.5 and is involved in the permeability barrier homeostasis, the cohesion of the SC, the regulation of the microbiome, and the down-regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokine signaling [51][1]. Different endogenous mechanisms account for the global reduction in the pH of the SC, including the hydrolyzation of phospholipids into FFA by phospholipases (sPLA2), the acidification by the sodium-hydrogen antiporter type 1 (NHE1), the catabolism of FLG into free amino acids including trans-urocanic acid and the release of protons from melanin granules.

The natural-moisturizing factors (NMFs) of SC is produced upon cornification. It comprises amino acids and their derivatives (pyrrolidone carboxylic acid and urocanic acid) resulting from the proteolysis of epidermal FLG. Changes in the NMFs alter the epidermis pH and lipids, indicating an interdependence between the chemical and the physical barrier functions [52,53,54][2][3][4]. Other components of the NMFs include lactates, urea, and electrolytes which also contribute to the pH and the state of hydration of the SC. Secretions from the sebaceous glands, containing triglycerides, wax esters, and squalene, are delivered directly onto the top of SC and add up to the water holding capacity and maintenance of the low pH. Indeed, bacteria and yeasts from the epidermis microbiome hydrolyze triglycerides into FFA, contributing to the acidification of the skin.

Sweat is not only involved in thermoregulation but is also able to increase and maintain skin hydration [55][5]. Urea and lactic acid present in sweat help in moisture retention by SC and make part of NMF. Eccrine sweat contains a large number of minerals, proteins, proteolytic enzymes, AMPs, and various inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1, IL-6, and IL-31, which can act as danger signals by activating keratinocytes [56][6]. The acidic mantle at the skin surface is also partially constituted by sweat. Kazal-type 5 (SPINK5) protease inhibitor, which contributes to maintaining epidermal homeostasis, and cysteine A protease inhibitor, which serves as the first line of defense against allergens with cysteine protease activity, are also secreted with sweat. As sweat is delivered onto the skin surface, it has no direct contact with living keratinocytes in healthy skin. However, in the skin with a defective cutaneous barrier, the leakage of sweat into the epidermis and the dermis causes not only chronic inflammation associated with itching sensation but also dry skin [57][7].

3. Role of the Microbiome in Skin

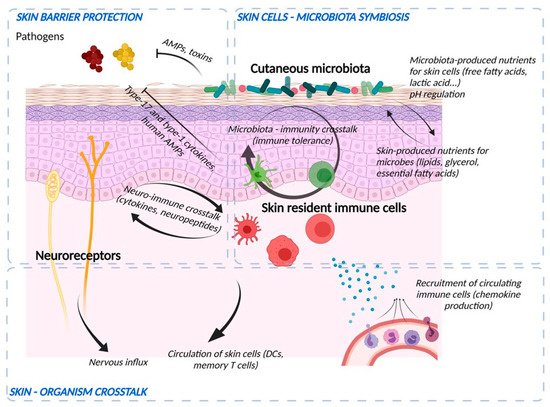

The skin’s natural microbiome colonizes the epidermal surface (Figure 2). The composition of the cutaneous microbiome includes bacteria, fungi, and viruses, and is fairly stable. Culture-independent genomic approaches have shown that, in contrast to the gut microbiome, the skin microbiota are dominated by Actinobacteria with an abundance of Gram-positive bacteria, such as Staphylococcus, Propionibacterium, and Corynebacterium species [58][8]. The composition of microbial communities depends on the skin site, with changes in the relative abundance of bacterial taxa associated with moist, dry, and sebum-rich microenvironments. Sebaceous sites are dominated by lipophilic Propionibacterium species, whereas bacteria that thrive in humid environments, such as Staphylococcus and Corynebacterium species, are preferentially abundant in moist areas, including the bends of the elbows and the feet.

Figure 2. Crosstalk between microbiological, immunological, and sensory nerve barriers of the epidermis. Bacteria and skin cells are organized in a symbiosis in which nutrients are shared and protection from environmental hazards (e.g., pathogens) is provided by the different actors. Bacteria produce their own AMPs and stimulate immune cells and keratinocytes to induce immune vigilance and modulate the epidermal structure. In return, the epidermis produces nutrients and ligands essential for the establishment of commensal flora and develops an anti-pathogen defense via the production of AMPs, the action of cells such as neutrophils and macrophages, the production of cytokines to potentiate the action of these cells and chemokines to recruit them from the bloodstream. Immune cells and keratinocytes also interact with nerve endings (“neuroinflammation”) to potentiate the response to pathogens and participate in sensory awareness. Finally, the skin barrier informs the body by sending nerve impulses and circulating skin cells to lymphoid organs.

Bacterial commensal colonization of human skin is vital for the defence-training and maintenance of the skin’s innate and adaptive immune functions [59][9]. Staphylococcus epidermidis, belonging to the natural cutaneous microbiome, inhibits colonization by the pathogenic Staphylococcus aureus and induces expression of AMPs resulting in S. epidermidis-orchestrated innate immune alertness. Additionally, it may enhance epidermal barrier function through the increased expression of TJ proteins occludin and ZO-1 [60][10].

Tight regulation of the composition of the microbiome is provided by the epidermis pH and by the skin immune system. Efficacy of the epidermal barrier is, thus, the outcome of the threefold crosstalk between the chemical barrier, the skin immune system, and skin microbiota. The skin microbiome participates in transmission of xenobiotic environmental signals to the functional immune network of the skin [61][11].

4. Immunological Aspects of the Barrier Function

The immune barrier of the skin comprises a variety of resident immune cells populating epidermis and dermis (Figure 2) [1][12]. Constitutive sentinels of the immune system, such as several types of resident antigen-presenting cells e.g., epidermal Langerhans cells and dermal dendritic cells, cooperate with keratinocytes and adaptive tissue-resident memory lymphocytes to maintain the surveillance against foreign aggressions [62][13].

An important part of this barrier belongs to the innate defense system. AMPs are considered a rapid and first-line response of the innate immune system to microbial pathogens. Together with their antimicrobial effects, AMPs also exert immunomodulatory effects by inducing cell migration, proliferation, and differentiation, regulating cytokine/chemokine production, and sustaining the barrier function of the skin [63][14]. AMPs, such as LL-37, human beta-defensins, and S100A7 are produced and released by keratinocytes and immune cells [64][15]. This non-specific immunity is effective against a wide range of pathogens and contributes to the regulation of the skin microflora [65][16].

Altogether, this immune armada efficiently senses microbial danger signals via pathogen- and damage-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs and DAMPs) and specific pattern recognition receptors that include Toll-like receptor (TLR), Nod-like receptor (NLR), and C-type Lectin receptor (CLR). Initiation of an adequate immune response results in tissue inflammation and further barrier disruption aimed at clearing the xenobiotic invasion. Beyond this necessary but locally harmful action, resident immune cells subsequently contribute to skin barrier repair and re-establishment of homeostasis.

Several feedback mechanisms exist between various functional components of the skin barrier. The immune defense system is influenced by other skin barrier components and vice versa. AMP expression is thus regulated by the cutaneous microbiome. Activation of various TLRs enhances TJ barrier function by up-regulation of the expression of claudins, ZO-1, and occludin [66][17]. In contrast, proinflammatory cytokines like interleukin 1β and tumor necrosis factor alpha have been shown to differently modulate TJ function [67][18]. Furthermore, TJs together with the functional SC barrier are involved in the regulation of innate immunological barrier because they limit the contact of living epidermal cells expressing pattern recognition receptors with the external danger signals including pathogens [68][19].

5. Participation of the Sensory Neuronal System in the Barrier Function

The skin is a sensory organ that comprises a large range of sensory receptors associated with non-neuronal components (Figure 2), such as Meissner corpuscles, Pacini corpuscles, and Ruffini endings in the dermis or Merkel cell complexes in the epidermis [69,70][20][21]. Besides, intra-epidermal nerve fibers (IENF), classified as C- and Aδ-fibers, unmyelinated, and thickly myelinated, respectively transduce stimuli via specific receptors, in particular Transient Receptor Potential (TRP) ion channels [71][22]. Originally described as “touch corpuscles” by Friedrich Merkel in 1875, Merkel complexes are groups of specialized cells in the epidermis of glabrous skin that are innervated by sensory fibers, via synaptic junctions. Merkel cells are anchored within the epidermis by thin cytoplasmic protrusions projecting to keratinocytes and by desmosomes [70][21]. The IENF are not the exclusive transducers of pain and itch. While TRP is expressed both by sensory neurons and keratinocytes, its specific and selective activation on keratinocytes is sufficient to induce pain [71][22]. The entire epidermis may be thus considered as a sensory tissue [72][23]. IENF can communicate with different cell populations in the different layers of the skin by releasing various types of neuropeptides. Almost all cutaneous cells express functional receptors for neuropeptides, through which they receive signals from the nervous system. In turn, skin cells produce neuropeptides and neurotrophins, which stimulate nerve fibers. This exchange creates a positive bidirectional feedback loop. There is increasing evidence that the cutaneous nervous system modulates physiological and pathophysiological effects including cell growth and differentiation, immunity, and inflammation as well as tissue repair. Skin innervation is part of the peripheral nervous system. This cutaneous nervous system is constantly receiving and responding to various types of stimuli which can be either physical (thermal, mechanical, electrical, light), chemical, or produced by allergens, haptens, microbiological agents, trauma, or inflammation. Cutaneous nerves can also respond to stimuli from the blood stream and react to emotions. Moreover, the central nervous system can modulate a large number of functions within the skin including vasomotricity, thermoregulation, piloerection, gland and cell secretion, tissue growth and differentiation, wound healing, immune response, and inflammation [73,74][24][25]. This happens either directly, via efferent autonomic nerves and brain-derived mediators or indirectly, through the immune cells and adrenal glands relaying central signals.

The epidermis is thought to protect sensory nerves from overexposure to environmental stimuli, and epidermal barrier impairment leads to pathological conditions associated with itch, such as atopic dermatitis. Epidermal nerve endings are pruned through interactions with keratinocytes to stay below the TJ barrier, and disruption of this mechanism may lead to aberrant activation of epidermal nerves and pathological itch [75][26].

The epidermis closely interacts with nerve endings and both epidermis and nerves produce substances for mutual sustenance. Several factors including pH gradient, skin barrier integrity, irritant exposure, and the microbiome can modulate these interactions. Complex interplay exists between the immune and sensory nervous systems through the activation of protease-activated receptors (PARs) by endogenous and microbiome-derived proteases and the release of cytokines, neuropeptides, and neurotrophins by both keratinocytes and neurons [73,76][24][27]. Activation of PARs can be linked to downstream activation of transient receptor potential (TRP) of ion channels, e.g., ENaC that mediate neurogenic inflammation and pain and participates to the production and the secretion of lipids by the epidermis [77][28]. Furthermore, PAR2 might contribute to epidermal barrier impairment by compromising TJs integrity and claudin-1 expression [78][29].

References

- Elias, P.M. The how, why and clinical importance of stratum corneum acidification. Exp. Dermatol. 2017, 26, 999–1003.

- Bhattacharya, N.; Sato, W.J.; Kelly, A.; Ganguli-Indra, G.; Indra, A.K. Epidermal Lipids: Key Mediators of Atopic Dermatitis Pathogenesis. Trends Mol. Med. 2019, 25, 551–562.

- Haftek, M.; Teillon, M.H.; Schmitt, D. Stratum corneum, corneodesmosomes and ex vivo percutaneous penetration. Microsc Res Tech. 1998, 43, 242–249.

- Patrick, G.J.; Archer, N.K.; Miller, L.S. Which Way Do We Go? Complex Interactions in Atopic Dermatitis Pathogenesis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2021, 141, 274–284.

- Shiohara, T.; Mizukawa, Y.; Shimoda-Komatsu, Y.; Aoyama, Y. Sweat is a most efficient natural moisturizer providing protective immunity at points of allergen entry. Allergol. Int. 2018, 67, 442–447.

- Dai, X.; Okazaki, H.; Hanakawa, Y.; Murakami, M.; Tohyama, M.; Shirakata, Y. Eccrine sweat contains IL-1α, IL-1β and IL-31 and activates epidermal keratinocytes as a danger signal. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e67666.

- Murota, H.; Yamaga, K.; Ono, E.; Murayama, N.; Yokozeki, H.; Katayama, I. Why does sweat lead to the development of itch in atopic dermatitis? Exp. Dermatol. 2019, 28, 1416–1421.

- Byrd, A.; Belkaid, Y.; Segre, J. The human skin microbiome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 143–155.

- Brandwein, M.; Bentwich, Z.; Steinberg, D. Endogenous Antimicrobial Peptide Expression in Response to Bacterial Epidermal Colonization. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1637.

- Ohnemus, U.; Kohrmeyer, K.; Houdek, P.; Rohde, H.; Wladykowski, E.; Vidal, S.; Horstkotte, M.A.; Aepfelbacher, M.; Kirschner, N.; Behne, M.J.; et al. Regulation of epidermal tight-junctions during infection with exfoliative toxin-negative Staphylococcus strains. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2008, 128, 906–916.

- Belkaid, Y.; Segre, J.A. Dialogue between skin microbiota and immunity. Science 2014, 346, 954–959.

- Yang, G.; Seok, J.K.; Kang, H.C.; Cho, Y.Y.; Lee, H.S.; Lee, J.Y. Skin Barrier Abnormalities and Immune Dysfunction in Atopic Dermatitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2867.

- Nguyen, A.V.; Soulika, A.M. The Dynamics of the Skin’s Immune System. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1811.

- Nguyen, H.L.T.; Trujillo-Paez, J.V.; Umehara, Y.; Yue, H.; Peng, G.; Kiatsurayanon, C.; Chieosilapatham, P.; Song, P.; Okumura, K.; Ogawa, H.; et al. Role of Antimicrobial Peptides in Skin Barrier Repair in Individuals with Atopic Dermatitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7607.

- Clausen, M.L.; Agner, T. Antimicrobial Peptides, Infections and the Skin Barrier. Curr. Probl. Dermatol. 2016, 49, 38–46.

- Coates, M.; Blanchard, S.; MacLeod, A.S. Innate antimicrobial immunity in the skin: A protective barrier against bacteria, viruses, and fungi. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1007353.

- Kuo, I.H.; Carpenter-Mendini, A.; Yoshida, T.; McGirt, L.Y.; Ivanov, A.I.; Barnes, K.C.; Gallo, R.L.; Borkowski, A.W.; Yamasaki, K.; Leung, D.Y.; et al. Activation of epidermal toll-like receptor 2 enhances tight junction function: Implications for atopic dermatitis and skin barrier repair. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2013, 133, 988–998.

- Kirschner, N.; Poetzl, C.; von den Driesch, P.; Wladykowski, E.; Moll, I.; Behne, M.J.; Brandner, J.M. Alteration of tight junction proteins is an early event in psoriasis: Putative involvement of proinflammatory cytokines, Am. J. Pathol. 2009, 175, 1095–1106.

- Kuo, I.H.; Yoshida, T.; De Benedetto, A.; Beck, L.A. The cutaneous innate immune response in patients with atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013, 131, 266–278.

- Talagas, M.; Misery, L. Role of Keratinocytes in Sensitive Skin. Front. Med. 2019, 6, 108.

- Zimmerman, A.; Bai, L.; Ginty, D.D. The gentle touch receptors of mammalian skin. Science 2014, 346, 950–954.

- Pang, Z.; Sakamoto, T.; Tiwari, V.; Kim, Y.S.; Yang, F.; Dong, X.; Güler, A.D.; Guan, Y.; Caterina, M.J. Selective keratinocyte stimulation is sufficient to evoke nociception in mice. Pain 2015, 156, 656–665.

- Boulais, N.; Misery, L. The epidermis: A sensory tissue. Eur. J. Dermatol. 2008, 18, 119–127.

- Yosipovitch, G.; Misery, L.; Proksch, E.; Metz, M.; Ständer, S.; Schmelz, M. Skin Barrier Damage and Itch: Review of Mechanisms, Topical Management and Future Directions. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2019, 99, 1201–1209.

- Chiu, I.M.; von Hehn, C.A.; Woolf, C.J. Neurogenic inflammation—The peripheral nervous system’s role in host defense and immunopathology. Nat. Neurosci. 2012, 15, 1063–1067.

- Takahashi, S.; Ishida, A.; Kubo, A.; Kawasaki, H.; Ochiai, S.; Nakayama, M.; Koseki, H.; Amagai, M.; Okada, T. Homeostatic pruning and activity of epidermal nerves are dysregulated in barrier-impaired skin during chronic itch development. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 8625.

- Choi, J.E.; Di Nardo, A. Skin neurogenic inflammation. Semin. Immunopathol. 2018, 40, 249–259.

- Charles, R.P.; Guitard, M.; Leyvraz, C.; Breiden, B.; Haftek, M.; Haftek-Terreau, Z.; Stehle, J.C.; Sandhoff, K.; Hummler, E. Postnatal requirement of the epithelial sodium channel for maintenance of epidermal barrier function. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 2622–2630.

- Nadeau, P.; Henehan, M.; De Benedetto, A. Activation of protease-activated receptor 2 leads to impairment of keratinocyte tight junction integrity. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018, 142, 281–284.

More