Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Li Du and Version 3 by Dean Liu.

Strategies to enhance sulfur loading and utilization and compaction of the cathode are crucial objectives in accelerating the industrial realization of Li–S pouch cells.

- lithium–sulfur batteries

- pouch cells

- lithium anode

- polysulfide shuttling

1. Introduction

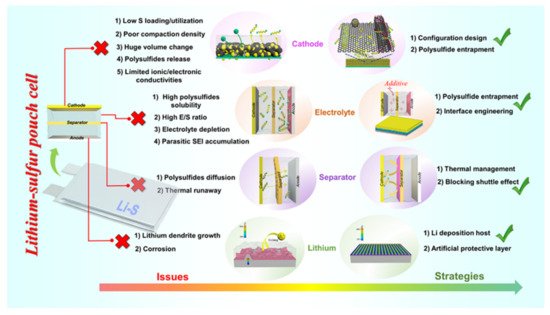

Li–S cells have many intrinsic limitations that have been elaborately investigated and reviewed in previous literature [1][2][9,10]. Specifically, the energy density and cyclability of Li–S coin cells are limited by (1) loading and utilization of sulfur active material in the cathode composite, (2) polysulfide dissolution and shuttling in liquid electrolytes, (3) electrolyte depletion and interfacial degradation, and (4) dendritic lithium growth and the evolution of “dead Li”. Furthermore, the gravimetric and volumetric energy densities of Li–S cells explored in the research community are restricted by excessive usage of electrolyte and lithium metal during experimentation. Studies on these issues bring new understanding to the drawbacks of scaling small-scale cells used in research laboratories to large industrial-scale Li–S pouch cells [3][4][11,12]. Many of the aforementioned difficulties of the Li–S system are exacerbated when moving to lean electrolyte (low E/S ratio) and limited Li anode reservoir conditions; Li–S pouch cells cycled under these protocols suffer from much faster capacity degradation (Table 1). Additionally, the gravimetric energy density and cycling stability of large-scale Li–S pouch cells are significantly affected by sulfur active material mass loading, volumetric cell expansion, electrolyte depletion, thermal release, and the Li metal anode during practical operation (Figure 1) [5][7].

2. Electrolytes for Li–S Pouch Cells

The electrolyte not only provides ionic transport between the two electrodes in a Li–S battery but also serves as a reaction medium for the conversion of the sulfur species within the cathode. Electrolyte decomposition at the cathode and anode interfaces is the most prominent cause of performance degradation in Li–S pouch cells; it can lead to poor sulfur active material utilization, low rate capability, and a short cycle life [9][51]. In Li–S pouch cells with excess electrolyte (high E/S ratio), the cathode material is completely wet and the cell has a prolonged cycle-life because electrolyte depletion takes longer to occur [10][19]. However, a high E/S ratio leads to relatively low gravimetric and volumetric energy densities in cells; as the areal sulfur loading of a cell increases, the impact of the E/S ratio of the cell on the gravimetric energy density increases [11][20]. Thus, to enhance the specific capacity of Li–S pouch cells, it is of the utmost importance to improve their cyclability under lean electrolyte conditions (low E/S ratio).

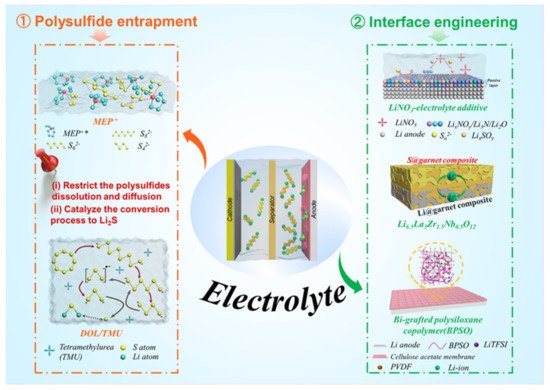

Generally, Li–S pouch cells operating under lean electrolyte conditions face three main challenges: (1) the kinetics of cathode redox reactions are slowed and cause uneven wetting of the active materials, (2) the dissolution of polysulfide species causes severe electrolyte depletion, and (3) the electrochemically induced interfacial reactions with Li metal consume electrolyte to form a solid–electrolyte interphase (SEI) [10][12][19,52]. Additionally, the effect of the E/S ratio on the energy density of the cathode composite varies with sulfur loading and compaction density, even at E/S ratios as low as 3.0 µL mg−1 [13][53]. For large-scale Li–S pouch cells, the E/S ratio should be calculated and chosen based upon the cathode/anode composition and configuration. To enhance the kinetics of the electrochemical processes of the cell and reduce the effects of side reactions under lean electrolyte conditions, additives or novel electrolyte compositions are suggested to catalyze sulfur conversion, suppress the shuttle effect, and/or enable the formation of a stable passivation layer on the lithium metal anode (Figure 23) [13][14][53,54].

Figure 23. Strategies and perspectives to enable Li–S pouch cells under lean electrolyte conditions. (1) Regulate polysulfide species generated during the conversion process. (2) Engineering the interface between the electrolyte and the lithium metal anode.

High-concentration electrolyte (HCE) systems can simultaneously inhibit the shuttle effect of lithium polysulfide and the growth of lithium dendrites. However, due to the use of a large amount of expensive Li salt, the cost of the electrolyte has always been high. In addition, the viscosity of the electrolyte will increase drastically, while the wettability will also decrease along with the high concentration of electrolyte. Accordingly, there will not be enough free solvent molecules to dissolve polysulfides, and the ion diffusion and reaction kinetics will be slowed [15][55]. This strategy does not seem to be the first choice for commercial Li–S batteries. Localized high-concentration electrolytes (LHCEs) show the advantages of high-concentration electrolytes and have the characteristics of low-concentration electrolytes with low viscosity and low cost [16][56]. Although LHCEs are promising candidates for the next generation of electrolytes, the ratio of various components in the electrolyte and the role of additives still require further research [17][57].

In addition, solid-state electrolytes are an alternative avenue of pursuit for Li–S pouch cells [18][19][58,59]. An all-solid-state Li–S pouch cell would negate any concern over polysulfide dissolution and shuttling. However, preliminary small-scale pouch cells with this approach have encountered dramatic problems [18][58]. Many of the solid-state electrolytes with sufficient ionic conductivity do not have an electrochemical stability window large enough to remain inert against lithium metal, causing sluggish Li+ transport across the lithium metal solid–electrolyte interface. The electrode–electrolyte interfaces also have poor mechanical integrality due to the nature of the solid–solid interface during charge/discharge cycling [7][20][17,60]. Attempts to accelerate the feasibility of solid-state electrolytes in Li–S pouch cells focus on interfacial engineering to avoid chemical and mechanical decomposition through such means as using thin-film solid-state electrolytes and softening interfacial contact during cycling (Figure 23) [21][22][23][61,62,63].

2.1. Strategies to Regulate Polysulfide Conversion under Lean Electrolytes

Uneven precipitation and accumulation of insulative sulfur/Li2S species can occur under lean electrolyte conditions, causing sluggish sulfur conversion in the cathode side. A high concentration of polysulfide species and a low electrolyte viscosity result in a charge carrier concentration gradient during cycling and cause a large voltage hysteresis [24][25][64,65]. This hysteresis limits the utilization of active material and the rate performance of the cell, making the mediation of polysulfide species in the electrolyte a greater challenge to overcome when a low E/S ratio is used. Electrolyte additives or organic solvents with a high donor number have been shown to increase the solvation of polysulfide species in the electrolyte and simultaneously trap high-order polysulfides to catalyze their conversion to Li2S, suppressing the shuttling effect.

Zhang and coworkers introduced a large size N-methyl-N-ethyl pyrrolidinium (MEP+) cation that binds and stabilizes polysulfide species in the electrolyte (Figure 3) [14][54]. From hard–soft acid–base theory (HSAB), MEP+ as a soft acid interacts strongly with soft bases—such as Sn2– species—which inhibits the disproportionation of polysulfides in the electrolyte. This addition of MEP+ to the electrolyte enabled a 5 Ah pouch-type LSB that showed a high initial energy density of over 300 Wh kg−1 and a cycle-life of 100 cycles. High-dielectric solvents are expected to enhance the solvation of sulfur species and improve sulfur utilization in the cathode. Modified ether electrolytes based on a high-ε aprotic solvent of tetramethylurea (TMU) (Figure 3) have been proposed to regulate the viscosity and polysulfide conversion in cells with a low E/S ratio [13][53]. Combined with DOL, a DOL/TMU electrolyte can efficiently solvate S3•– radicals, accelerate polysulfide conversion, and have good anodic stability against Li metal. A pouch cell using a TMU-based high-ε electrolyte delivered a sulfur utilization of 91% and a high energy density of 324 Wh kg−1 with an E/S ratio of 3 μL mg−1. Kaskel et al. combined tetramethylene sulfone (TMS) with a solvent blend of 1,1,2,2-tetrafluoroethyl-2,2,3,3-tetrafluoropropyl ether (TTE) to mediate polysulfide solubility within the cell [26][66]. This system (LiTFSI in TMS/TTE) had a reduced polysulfide concentration gradient during cycling and achieved a high Coulombic efficiency above 94% with an E/S ratio below 2.6 μL mg−1, offering a promising route toward practical high-energy Li–S pouch cells.

Li–S pouch cells with a high energy density can be obtained with a low E/S ratio by mediating the solvation of sulfur species and the conversion kinetics via the electrolyte. The compromise between high sulfur utilization and a low E/S ratio is also associated with the composition and compaction density of the cathode composite. Thus, although the electrolyte must be given careful consideration for optimum large-scale Li–S pouch cell performance, maximizing the cell’s energy density with a high sulfur loading and low E/S ratio needs further elucidation before it becomes a practically viable approach.

2.2. Interfacial Engineering

Li–S pouch cells with a high sulfur loading and a low E/S ratio can have a higher concentration of polysulfides within the electrolyte. This effect leads to more pronounced shuttling and severe chemomechanical reactions at the electrolyte–electrode interfaces that can form an unstable SEI [25][65]. An unstable SEI layer at the electrode–electrolyte interface allows polysulfides to penetrate the interior of the Li anode and form new SEI and “dead Li”, further depleting both the electrolyte and the lithium metal anode during extended cycling. Moreover, the thick SEI layer blocks Li+ and electron transfer to the lithium anode and can cause a localized current density higher than the critical current density for forming lithium dendrites. This high localized current density triggers the onset of lithium dendrite formation, which can ultimately short-circuit the cell. Interfacial engineering is essential in preventing these catastrophic outcomes in the practical operation of pouch cells with high sulfur loading under lean electrolyte conditions. The main electrolyte-tailoring strategies used to improve the performance of the anode–electrolyte interface in Li–S pouch cells are (1) in situ formation of a reinforced passivation layer on the Li anode surface via an electrolyte additive, (2) using a solid-state electrolyte to block polysulfide shuttling and suppress lithium dendrite growth, and (3) employing a polymer electrolyte with limited polysulfide species solubility and high stability against a Li metal anode.

2.2.1. Additives in Liquid Electrolyte for SEI Construction

Li–S cells typically employ ether-based electrolytes, in which lithium salts (LiTFSI) are dissolved in a combination of 1,3-dioxolane (DOL) and 1,2-dimethoxyethane (DME) solvents [27][67]. Lithium nitride (LiNO3) is a widely adopted additive for these liquid electrolytes (Figure 3) owing to its ability to effectively suppress the decomposition of the electrolytes and induce the polymerization of DOL to form a polymeric layer to passivate the lithium metal anode [28][68]. LiNO3 also aids in hindering the negative effects of dissolved polysulfide species on the Li metal anode by oxidizing the polysulfides to LixSOy. SEI layers formed in the presence of LiNO3 have been shown to have a more optimal composition for Li–S pouch cell performance. However, the exact composition of this SEI is yet to be identified, it is known to be a complex mixture of organic (e.g., ROLi, ROCOLi, RCOOLi, where R is the organic group) and inorganic compounds (e.g., LiF, Li2O, Li3N, Li2S, LiSxOy, LixNOy) [21][29][30][31][50,61,69,70]. Table 13 presents a performance comparison of Li–S pouch cells with and without LiNO3 additives in their electrolytes using various cathode architectures. The SEI layer formed with a LiNO3 additive effectively suppresses parasitic reactions of the polysulfides with lithium metal to prevent the formation of Li dendrites in the Li–S pouch cells during operation. Long-term galvanostatic cycling tests showed that pouch cells with a LiNO3 electrolyte additive maintained a stable capacity for up to 100 cycles with a sulfur loading of 6 mg cm−2 [32][71]. Other functional additives with a high donor number, such as salts containing the NO3− anion, have also been explored in Li–S cells to suppress electrolyte decomposition on the Li metal by regulating the Li+ solvation shell. This regulation enhances the cycling performance of the lean electrolyte Li–S pouch cells. Fluorinated solvents with lower viscosity can form a LiF-rich SEI on the lithium metal. LiF is regarded as a good SEI component for stabilizing the lithium metal surface and allowing Li-ion transfer while suppressing dendrite nucleation. This enhanced LiF-rich SEI is effective in yielding a safe and practical Li–S cell with improved cycle life [33][72].

Table 1. Electrochemical performance of Li–S pouch cells with liquid electrolytes.

| Cathode | Areal Sulfur Loading (mg cm−2) |

Electrolyte | Additive | Anode | C Rate | Specific Capacity (mAh g−1) |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S/Ketjenblack | ~1.3 | DOL/DME | – | LAGP/Li metal | 0.5 | ~1000 | [15] |

| S/Ketjenblack | ~4.0 | DOL/DME | – | Li3PS4/Li | 0.2 | ~1200 | [16] |

| S/CNTs | 2.5 | DOL/TMU | 0.3 M LiNO3 | Li metal | 0.05 | 1524 | [34] |

| S/Super C65 | ~3.9 | DOL/DME | 0.4 M LiNO3 | Li metal | 0.2 | 1205 | [2] |

| S/CNTs | 7.8 | DOL/DME | 1 wt% LiNO3 | Li metal | 0.1 | 1135 | [35] |

| S/CoNi@PNCFs | ~1.5 | DOL/DME | 0.1 M LiNO3 | Li/CoNi@PNCFs | 0.2 | ~1200 | [36] |

| RGO@S | 5.8 | DOL/DME | 0.2 wt% LiNO3 | Li metal | 0.1 | 1269 | [37] |

However, these functional additives are constantly consumed at both the anode and the cathode during cycling and cannot maintain a long cycle-life at the pouch cell level. Thus, exploring new electrolyte additives that can decrease parasitic side reactions and enhance the stability of the SEI layer in Li–S cells is a worthwhile endeavor for realizing industrially relevant Li–S pouch cells.

2.2.2. Inorganic Solid-State Electrolytes

Inorganic ceramic solid electrolytes do not solvate polysulfide species and are chemically/electrochemically stable with sulfide species, making them a prime candidate for Li–S cells with a high sulfur utilization. As shown in Figure 3, a porous–dense–porous trilayer garnet-type solid-state electrolyte was designed for a Li–S cell to block polysulfide shuttling and prevent lithium dendrite growth; the thick porous layer acts as a robust mechanical support and a sulfur host [22][62]. A 5 cm × 5 cm pouch cell with this trilayer garnet-type solid-state electrolyte showed a high energy density and stable cycling.

Sulfide-based solid electrolytes are easy to process, have high ionic conductivity, and have the lowest electronic conductivity at room temperature [38][75]. These characteristics allow them to be integrated into Li–S cells with limited volume and a soft interface contact. There are numerous techniques for obtaining optimal interfaces for Li+ transfer. Hot pressing, slurry coating, and the use of interfacial buffer layers are among the most popular methods for obtaining good interfacial compatibility in all-solid-state Li–S pouch cells with sulfide solid electrolytes [18][39][58,76]. Large-scale all-solid-state Li–S pouch cells with a sulfur cathode and Li10GeP2S12 electrolyte yield a high specific capacity of 1169 mAh g−1 and excellent cycling stability [40][77]. Although the sulfide solid electrolyte possesses high Li+ conductivity, its development is still hindered by many of its characteristics [18][58]. Narrow electrochemical window (1.5~2.5 V) and unstable electrode–electrolyte interface affect its long-term cycling performance.

Although the suppression of polysulfide shuttling and lithium dendrite growth in Li–S cells can be accomplished with solid-state electrolytes, there are still challenges in forming thin and dense electrolytes that maintain their mechanical integrity during cell packaging. This critical factor strongly hinders the practical feasibility of all-solid-state Li–S pouch cells.

2.2.3. Polymer-Based Solid Electrolytes

Polymer-based solid electrolytes are generally easy to process and have outstanding flexibility at room temperature [41][78]. Li–S pouch cells with a polymer-based electrolyte have been demonstrated to have negligible polysulfide shuttling while maintaining good interfacial contact with both electrodes. For polymer-based solid electrolytes, improving Li+ conductivity is of great significance for short-term cycling [42][79]. As for the long-term cycling of polymer-based solid electrolytes, determining how to suppress the growth of lithium dendrites is the first key point; for example, it could be improved by increasing mechanical strength [18][58]. Armand et al. introduced LiDFTFSI–PEO as a polymer electrolyte for LSBs [43][80]. In this system, a CF2H moiety is beneficial in strengthening the interaction between DFTFSI− and poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO). LiDFTFSI not only inhibits polysulfide shuttling but also induces the formation of a robust SEI on the lithium anode surface. Consequently, LiDFTFSI-based LSBs showed a high areal capacity and gravimetric energy density. Tao et al. integrated a ceramic Li-ion conductor (garnet-type Li7La3Zr2O12 (LLZO)) into PEO to form a composite solid-state electrolyte for all-solid-state Li–S cells that operate well at 37 °C [44][81]. Li–S pouch cells with a S@LLZO@C composite cathode and the PEO–LLZO composite electrolyte reached a specific capacity of 900 mAh g−1 and retained a capacity of 800 mAh g−1 after 200 cycles.

PVDF has a low donor number, which is proposed to restrain the formation of soluble polysulfides and manipulate the conversion of sulfur from a multistep “solid–liquid–solid” process to a single-step “solid–solid” reaction, making the PVDF electrolyte a competitive polymer electrolyte for Li–S cells (Figure 3) [19][59]. Fan et al. reported a composite polymer electrolyte (CPE) consisting of PVDF, bi-grafted polysiloxane copolymer (BPSO), and cellulose acetate (CA) [23][63]. This membrane delivers an ionic conductivity of 7 × 10−4 S cm−1 at 25 °C and forms a stable interface with a lithium anode, working well in an MCNT@S/90% (BPSO–150% LiTFSI)–10% PVDF+ CA/Li pouch cell.

The electrolyte is the most critical component of combating polysulfide shuttling and interfacial instability with the lithium metal anode in Li–S pouch cells. Bringing the E/S ratio to a commercially feasible value while circumventing the aforementioned issues only adds to the challenge. Additives and SEI reformation have been adopted to stabilize polysulfide species, decrease interfacial side reactions, and inhibit the nucleation of lithium dendrites in Li–S pouch cells. Thus, additives and progressive alternative electrolyte strategies are a promising route for discovering an optimal electrolyte composition that has moderate to low polysulfide solubility and good compatibility with lithium metal for fabricating competitive Li–S pouch cells.