Resection of the caudate lobe of the liver is considered a highly challenging type of liver resection due to the region’s intimacy with critical vascular structures and deep anatomic location inside the abdominal cavity. Laparoscopic resection of the caudate lobe is considered one of the most challenging laparoscopic liver procedures.

- caudate lobe

- spiegel lobe

- laparoscopic

- liver resection

1. Introduction

2. Safety and Efficacy of Laparoscopic Caudate Lobectomy

2.1. Long-Term Outcomes

Long-Term Outcomes

Though most of the studies reported a limited follow-up time of 90 days postoperatively, focusing solely on postoperative morbidity and not overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS), Oh et al. reported a median follow up time of 54.6 months, during which 2 out of 4 patients (50%) showed tumor recurrence. Patrikh et al. reported a rate of 42.9% of 5-year disease-free survival and a 76.2% of 5-year overall survival rate. There was one case of lesion recurrence at segment VIII 55 months following LCL, which was treated with radiofrequency ablation (RFA) and a case of carcinomatosis 9 months after the initial resection, treated with adjuvant systemic chemotherapy. The median follow-up time among other studies (Cheung, Wan et al., Dulucq et al., Ho et al., Li et al. and Chen et al.) reached 7.5 months during which no disease recurrence was detected (12, 6, 7, 1, 8 and 13), whereas Patrikh et al. reported the longer follow-up period extending up to 43 months. No deaths were reported in any of the studies in the postoperative observation period (Table 13).Comparative Studies

| Author | Follow-Up (Months) |

Adjuvant Chemotherapy (%) | Recurrence, N (%) | Overall Survival (Months) | Disease-Free Survival (Months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cheung [17] |

12 | 1 (100%) |

No | 12 | 12 |

| Wan et al. [18] |

6 | 1 (100%) |

No | 6 | 6 |

| Dulucq et al. [19] |

7 | 1 (100%) |

No | 7 | 7 |

| Ho et al. [20] |

1 | n/a | No | 1 | 1 |

| Oh et al. [21] |

54.6 (12.9–86.7) a |

1 (25%) |

2 (50%) |

54.6 (12.9–86.7) a |

32 (9–55) a |

| Li et al. [22] |

8 a | n/a | n/a | 8 a | 8 a |

| Chen et al. [23] |

13 (3–56) a |

n/a | n/a | 13 (3–56) a |

n/a |

| Kyriakides et al. [24] | n/a | No | No | n/a | n/a |

| Parikh et al. [25] | 43(4–149) a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Sun et al. [26] | n/a | n/a | 13.3% | n/a | n/a |

| Ruzzenente et al. [27] | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Capelle et al. [15] |

14(10–23) a | n/a | 129(54.5%) | 85% c | 10 |

2.2. Comparative Studies

All six studies reported a shorter length of stay for patients undergoing LCL compared to the OCL group. Only three studies reported comparison for R0 resection. In the first one (Xu et al.), though in every specimen the malignant lesion was totally removed, 8 out of 18 specimens in the LCL group had a surgical margin <1 cm compared to 28 out of 36 specimens for the OCL group having a surgical margin of <1 cm demonstrating a statistically significant difference between the two groups. This was not confirmed by Patrikh et al., who reported solely R0 resections in the LCL group and 8 out of 9 R0 resections in the OCL group, respectively. Ruzzenente et al. reported 26 out of 30 R0 resections for the LCL group compared to 27 out of 30 R0 resections for the OCL group after the propensity-matching score.3. Summary

LCL is a safe and efficient alternative to open resection for selected patients when performed by experienced hepatobiliary surgeons. This minimally invasive approach combines a low overall morbidity rate of 16.3%, as well as low mortality. Comparative studies also substantiate these outcomes, reporting lower morbidity between laparoscopic and open caudate lobectomy. Moreover, aside from being a safe alternative, is also efficient, with a 98% rate of R0 resections and a 3.1% rate of conversion to open.

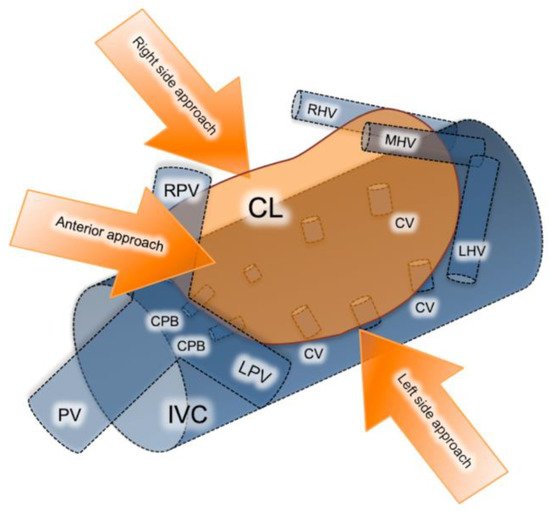

Resections of primary and metastatic lesions located within the caudate lobe are considered technically challenging, due to its deep intra-abdominal location and proximity to major vascular structures. The caudate lobe entails three distinct subsegments: (a) Spiegel’s lobe, located behind ligamentum venosum and on the left of the inferior vena cava (IVC); (b) the caudate process, extending to the left and useful in traction of the caudate lobe; and (c) the paracaval portion (Couinaud’s segment IX) corresponding to the dorsally located hepatic tissue in front of the inferior vena cava. Left and right portal veins, along with the hilar bifurcation area, provide the branches supplying the caudate lobe subregions, while short hepatic veins drain blood directly to the IVC [28][29][41,42].

Resection of the caudate lobe remains one of the most demanding resections, even through the open approach, while proper management of the short hepatic veins is of cardinal importance. Laparoscopy offers caudal-to-cephalad vision, which results in better exposure and control of the short hepatic veins. Other advantages include proper staging and determination of resectability since tumor seeding, and occult liver and lymph node metastases are identified intraoperatively [30][31][43,44]. However, laparoscopy poses a risk of massive intraoperative bleeding occurring from the anterior IVC, which may occur when dealing with tumors larger than 5cm, potentially invading the IVC and found close to the hilum or major hepatic veins [32][45]. In these situations, obtaining an adequate resection margin, despite laparoscopy’s aforementioned advantages, can be challenging.

There are three different approaches for isolated laparoscopic excision of the caudate lobe described in the literature including the left, right and anterior trans parenchymal, each chosen depending on the tumor size and location (Figure 12) [33][23]. Decision on which approach is more suitable is made based on tumor localization and size. The right-sided approach is usually reserved for bulky tumors. Taking into consideration that this approach requires a complete rotation of the right lobe to the left in order to expose the caudate hepatic veins, it is quite difficult to perform laparoscopically. The left-sided approach on the other hand is preferred for smaller-size tumors located in the Spiegel process or paracaval portion. Lastly, the anterior trans parenchymal approach includes the performance of retrohepatictransparenchymal resection and suspension of the right lobe [33][23]. It is furthermore recommended by several authors as a preferred alternative for lesions exceeding 4cm in diameter, or lesions involving critical vascular structures such as the inferior vena cava IVC and short hepatic veins. From a technical standpoint, it prevents hepatic rotation and subsequent venous rupture, making it feasible to dissect the liver parenchyma along the IVC [30][43].