You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Ming Dong and Version 1 by Ming Dong.

PFotential distribution areas of wide nicheur sympatric breadthOstrya species (O. japonicahave and O. trichocarpa) wifferent significantly widergeographic range sizes. O. multinervis and O. rehderiana are narrow-ranged species with narrow potential geographical distributions. O. japonica and O. trichocarpa, bothan those of narrow niche breadth species (O. multinervis of which have wide potential geographical distributions, and O. rehderiana).re wide-ranged species.

- climate change

- conservation management

- geographic range size

1. Introduction

Geographic range size, the area in which a species occurred, is determined by intrinsic (e.g., propagule or body size, dispersal ability, population density) and extrinsic (e.g., local environmental conditions, topographical features) factors [1,2]. Among those complex closely related factors, the dominant factors are usually changing and may vary among organisms and species [3,4,5,6,7]. Numerous hypotheses have been proposed to explain the diversification in geographical range size among species and across space, such as geometric constraint [8], habitat area [9], climatic variability [3], dispersal ability [6], niche breadth [10].

Among the mentioned above, niche breadth–range size hypothesis states that geographic range size is positively associated with environmental niche breadth and has been supported in some species (e.g., Gaston and Spicer [11], Boulangeat et al. [12]; Botts et al. [13], Carrillo-Angeles et al. [14]; Yu et al. [15]; Vincent et al. [16]). Species with broad niche may have better adaptation to various environmental types than those with narrow niche [17,18,19,20]. If this hypothesis holds true, it can be inferred that species having wide distribution range currently will further widen their distribution ranges, while species having narrow distribution range currently will further narrow their distribution ranges, under changed climate in the future [21]. However, the positive relationship is still uncertain in different taxonomic groups; additional evidence is required to support this hypothesis [22,23,24].

Moreover, geographic range size is usually used to predict the extinction vulnerability or invasion risk of a given species [25,26]. Predicting the potential geographic distribution range size and identifying the dominant factors would underlie biodiversity conservation and management [27,28,29]. Species distribution models (SDMs) are practical to predict the potential geographic distribution under different climate scenarios [30,31], which have been widely used for the conservation of rare species [14,32,33,34]. Maximum entropy (Maxent) modeling is one of the most commonly used predictive methods in SDMs [35], which can achieve greater predictive accuracy than other methods with presence-only and biased sampling data [33,36,37,38]. Benefiting from the statistical mechanics, the Maxent approach is powerful modeling for geographic distributions of rare species with narrow ranges and presence-only data [39,40,41,42]. The Maxent approach also performed well for distribution prediction of widespread species [33,43,44].

2. Study Species

Genus Ostrya Scopoli (Betulaceae) contains 8 tree species, commonly named hop-hornbeam or ironwood due to their hard and heavy wood texture [45,46,47,48]. Ostrya contains some species having been regarded as threatened species, similar to Carpinus of the same family [34,42,48,49,50]. Ostrya species are distributed in the subtropical and temperate forests of China with five species recorded in Flora of China (http://www.efloras.org (accessed on 15 June 2020)) [49], including O. japonica, O. multinervis, O. rehderiana, O. trichocarpa, and O. yunnanensis. Based on the latest phylogenetic analysis [51], O. yunnanensis was treated as O. trichocarpa in data processing. Thus, four sympatric species of Ostrya were included in this study, i.e., O. japonica, O. multinervis, O. rehderiana, and O. trichocarpa [51].

All of the Ostrya species are deciduous trees with scaly and rough barks. The male inflorescences would be formed from April to July, blooming in the spring of next year [49]. O. japonica is widespread from southwest to northeast China, while the other three Ostrya species have few occurrence records and narrow distributions in China. The Ostrya species differ in distribution regions, including O. japonica distributed in temperate deciduous forests (985–2800 m a.s.l.), O. multinervis in subtropical mixed forests (600–1300 m a.s.l.), O. rehderiana in subtropical evergreen broad-leaved forests (200–400 m a.s.l.), and O. trichocarpa in subtropical moist broadleaf forests (956–2600 m a.s.l.) [49,51]. O. rehderiana and O. multinervis had similar wild geographic distribution in the last glacial maximum (LGM), but then the habitat of the former was reduced dramatically while the latter maintained a stable population size [52]. Furthermore, O. rehderiana is on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN)’s Red List of Threatened Species as critically endangered [50]. It is also among the first-class state protection wild plants in China based on the latest report [53]. Ostrya species have different geographic range sizes, providing an opportunity to test the niche breadth–range size hypothesis through expectations of the models using narrowly distributed rare versus widespread congeneric species.

3. Predict the distribution of Ostrya species

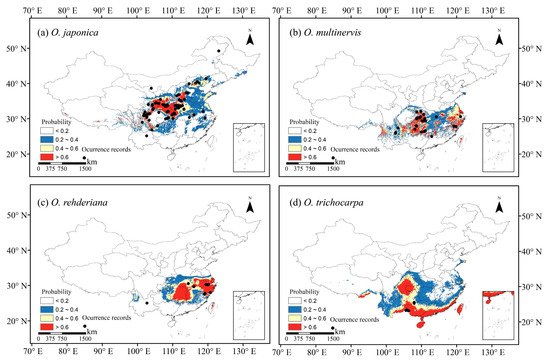

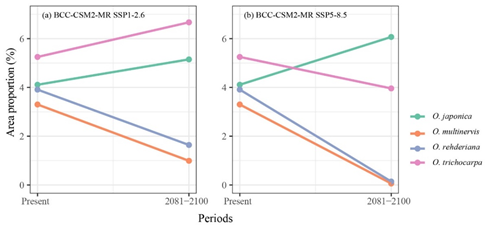

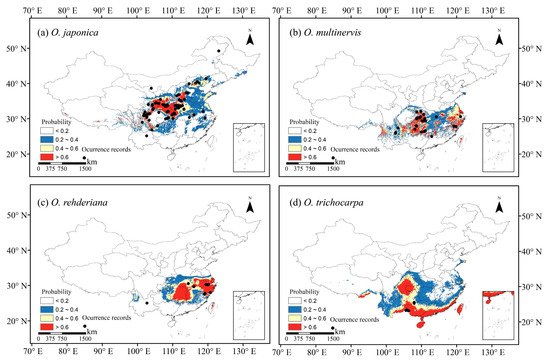

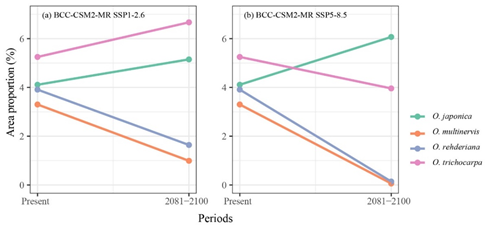

We collected occurrence records of four Ostrya species in China. We used Maxent to predict the potential distributions under present and future climate scenarios, and calculated the niche breadth of each species. Potential distribution areas of wide niche breadth species (O. japonica and O. trichocarpa) were significantly wider than those of narrow niche breadth species (O. multinervis and O. rehderiana)(Figure 1). In the future scenarios of global climate change, wide-ranged O. japonica would have wider potential distribution than in the current scenario, even expand their geographic range (Figure 2). Conversely, suitable habitats of narrow-ranged O. multinervis and O. rehderiana would be reduced strikingly in future scenarios as compared with in current scenario, might subjected to a high risk of extinction. Potential distribution range sizes of the Ostrya species would positively correlate with their niche breadths in future scenarios and their niche breadths would determine their distribution variation with climate change.

Figure 1. Occurrence records used in models and potential habitats in China of four species of Ostrya, i.e., O. japonica (a), O. multinervis (b), O. rehderiana (c), and O. trichocarpa (d), under present climate scenario. Note: Black dots represent the occurrence record locations of species in China. The values for species occurrence probability ranged between 0 and 1, i.e., least potential (<0.2), moderate potential (0.2–0.4), good potential (0.4–0.6), and high potential (>0.6).

Figure 2. Great probability habitat proportion shifts of four Ostrya species under climate scenarios, i.e., BCC-CSM2-MR SSP1-2.6 (a), and BCC-CSM2-MR SSP5-8.5 (b), between the present and 2081–2100 periods.

4. Contributions of Climate Variables

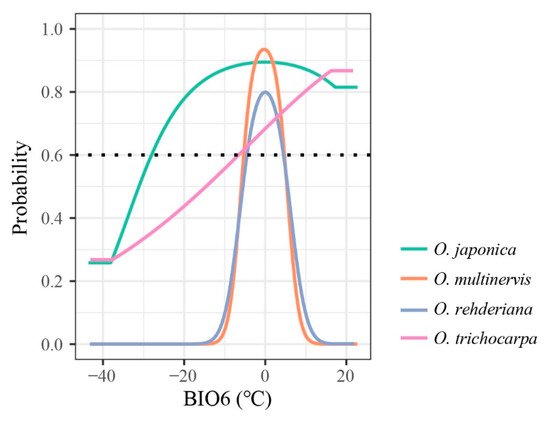

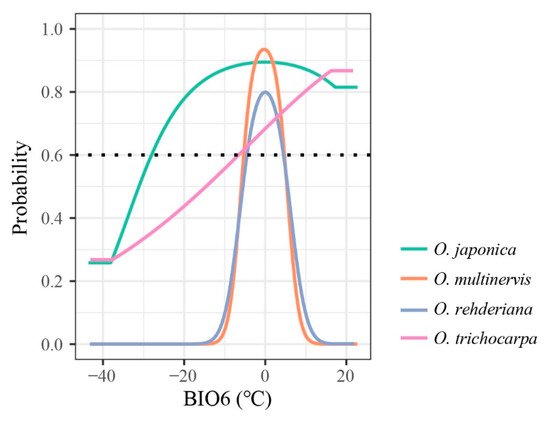

The minimum temperature of the coldest month (BIO6) was the principal temperature factor impacting the distributions of four Ostrya species, achieving 59.87% and 70.12% in the contributions of O. rehderiana and O. trichocarpa, respectively. The lowest temperature in winter around ±5 °C was suitable for the growth of O. multinervis and O. rehderiana, while the other two species could adopt a wider range of BIO6 (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Response curves of four Ostrya species, i.e., O. japonica, O. multinervis, O. rehderiana, and O. trichocarpa, presence probability affected by BIO6 (minimum temperature of coldest month, °C). The black dotted line represents that the probability of species existing is 0.6; species would archive high potential adaptation above this line.