Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Jae-Ku Oem and Version 2 by Amina Yu.

Avian influenza viruses (AIVs) are eight segmented, single-stranded negative-sense RNA viruses. Based on viral surface proteins, hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA), influenza viruses are classified into 18 HA and 11 NA subtypes. H1-16 and N1-9 have been detected in avian species, but H17-18 and N10-11 have been discovered only in bats. In particular, H5 and H7 are important subtypes because they have the potential to mutate into highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses (HPAIVs), causing severe clinical signs in poultry. According to previous research, the H7 low pathogenic avian influenza virus (LPAIV) is a precursor to the H7 HPAIV.

- avian influenza virus

- H7N7

- H7N9

- wild bird

1. Introduction

H7 LPAIVs have been detected in poultry farms worldwide, and wild birds are regarded as the origin of H7 LPAIVs [1][16]. In wild birds, all nine neuraminidase (N1–N9) are found in H7 AIVs, and H7N7 viruses are the subtypes reported in the largest number of countries geographically [2][17]. In South Korea, two LPAIVs, H7N3 and H7N8, were detected in domestic ducks in 2007 [3][18]. Since then, through active national surveillance, H7 LPAIVs have been isolated continuously from poultry farms and wild birds, and H7N7 viruses are the most common subtypes in wild birds [4][5][19,20]. Viruses isolated from poultry are closely related to wild bird isolates [4][19]. Moreover, some H7 LPAIVs isolated from wild birds showed pathogenicity in chickens in laboratory experiments.

AIVs can cause cross-species transmission from birds to mammals [6][21]. Avian-like H7N7 viruses have been detected in equines and pinnipeds [7][22]. In addition, there are many cases of H7 AIV infection in humans. The first case of H7N7 LPAIV directly transmitted from avian to human was reported in 1996 [8][23]. The infected woman had contact with a duck; she suffered from conjunctivitis and recovered naturally. In 2003, 89 cases of H7N7 HPAIV human infections occurred in the Netherlands [9][24]. One of the 89 patients died of acute respiratory distress syndrome, and three were confirmed to have contracted the virus through transmission between humans. A recent human infection of H7N7 AIVs was observed in three poultry workers in Italy in 2013, and they showed only conjunctivitis but no respiratory syndromes [10][25].

In 2013, the first case of human infection with H7N9 AIVs was reported in Shanghai, and since then, the H7N9 virus has shown five epidemic patterns in China [11][12][26,27]. The H7N9 viruses that occurred in 2013 were low pathogenic viruses but gradually mutated, resulting in high pathogenic strains in 2017 [13][14][6,28]. By 2019, 1568 cases of H7N9 human infections were confirmed worldwide, of which 616 deaths occurred [15][29]. However, after the introduction of H7N9 vaccine in poultry in 2017 in China, human infection with H7N9 virus has decreased dramatically [16][17][30,31]. Since September 2019, no human infection has been reported according to the FAO H7N9 situation update. Moreover, human infections related to other subtypes of H7 LPAIVs, such as H7N2 and H7N3, have often been reported since the 2000s [18][32]. Severe human infection with H7N4 originating from backyard poultry was reported in Jiangsu in 2018 [19][33].

In 2021, two AIVs, H7N7 and H7N9, were isolated from wild birds in South Korea. The molecular and phylogenetic characterizations of the two H7 Korean AIVs were analyzed in this study. In addition, pathogenicity in mammals was evaluated using a murine model.

2. Molecular Characterization of H7 AIV Isolates

The whole genomes of 20X-20 and 34X-2 viruses were obtained and deposited in GenBank with the accession numbers MZ803114-MZ803121 and MZ803125-MZ803132, respectively. The obtained full gene sequences of 20X-20 and 34X-2 were compared with four selected reference H7 viruses: A/chicken/Jiangsu/1/2018 (H7N4; chicken/1), A/Jiangsu/1/2018 (H7N4; Jiangsu/1), A/Anhui/1/2013 (H7N9; Anhui/1), and A/Italy/3/2013 (H7N7; Italy/3) (Table 1) (14, 15, 19). The Jiangsu/1, Anhui/1, and Italy/3 viruses originate from the H7 AIV and cause human infections. The chicken/1 virus was isolated from chickens in the backyard of humans infected with the Jiangsu/1 virus. The amino acid sequences of the HA cleavage sites of 20X-20 and 34X-2 were ELPKGR/GLF, indicating they are LPAIVs. The amino acids at positions 186, 190, 225, 226, 227, and 228 of the HA gene (numbering based on H3) are related to host receptor binding efficiency [20][21][22][43,44,45]. Except for 186V and 226L in Anhui/1, all H7 viruses had 186G, 190E, 225G, 226Q, 227S, and 228G, indicating that they prefer avian receptors over human receptors. NA stalk deletions (69–73) were not detected in any of the H7 viruses except for the Anhui/1 virus. However, drug resistance-associated mutations were identified at the 117 position in the NA genes of 20X-20 and 34X-2.

Table 1.

Molecular characterization of H7 avian influenza virus (AIV) isolates.

| Viral Protein | Amino Acid Residue | Virus Strains | Comments | Reference | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20X-20 (2021) | 34X-2 (2021) |

Chicken/1 (2018) |

Jiangsu/1 (2018) |

Anhui/1 (2013) |

Italy/3 (2013) |

||||||||

| HA | Cleavage site | ELPKGR/GLF | ELPKGR/GLF | ELPKGR/GLF | ELPKGR/GLF | ELPKGR/GLF | ETPKRRERR/GLF | LPAIV -monobasic |

[23] | [49] | |||

| A/red-crowned crane/South Korea/H1026/2017(H7N7) | 96.6% | G186V | G | G | G | G | V | G | Increased α2-6 binding | [22] | [45] | ||

| PB1 | A/red-crowned crane/South Korea/H1026/2017(H7N7) | 95% | A/wild_duck/South_Korea/KNU18-104/2018(H7N7) | 93.6% | E190D | E | E | E | E | E | |||

| PA | A/wild_duck/South_Korea/KNU18-106/2018(H7N7) | 99.1% | A/wild_bird/Eastern_China/1758/2017(H5N3) | 98.6% | E | [ | 20] | [43] | |||||

| Q/G225D | G | G | G | G | G | ||||||||

| HA | G | [ | A/wild_duck/South_Korea/KNU18-106/2018(H7N7) | 20 | ] | [ | 43] | ||||||

| 97.8% | A/wild_duck/South_Korea/KNU18-106/2018(H7N7) | 97.3% | Q226L | Q | Q | Q | Q | ||||||

| NP | A/common teal/Shanghai/NH110923/2019(H1N1) | 98.8% | A/duck/Mongolia/926/2019(H5N3) | L | Q | [ | 20] | [ | 99.3%43] | ||||

| S227N | S | S | S | S | S | S | |||||||

| NA | [ | 21 | ] | [ | 44 | ] | |||||||

| A/Anas platyrhynchos/South Korea/JB31-96/2019(H11N9) | G228S | G | G | G | G | G | G | [20] | [43] | ||||

| 98.2% | A/mallard/Korea/A15/2016(H7N7) | 97.4% | PB2 | L89V | V | V | V | V | V | V | Increased polymerase activity in mammalian cell lines and mice | [24] | [46] |

| I147T | I | I | I | I | I | T | [25] | [50] | |||||

| I292V | I | I | I | I | V | I | [26] | [51] | |||||

| G309D | D | D | D | D | D | D | [24] | [46] | |||||

| T339K | K | K | K | K | K | K | [24] | [46] | |||||

| K389R | R | R | R | R | K | R | [27] | [52] | |||||

| E627K | E | E | E | K | K | E | Increased virulence in mice | [28] | [53] | ||||

| D701N | D | D | D | D | D | D | [29][30] | [54,55] | |||||

| V598T/I | T | T | T | T | V | T | Increased polymerase activity in mammalian cell line | [27] | [52] | ||||

| PB1 | C38Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Increased polymerase activity in mammalian cell line and pathogenicity in chicken | [31] | [56] | |||

| D622G | G | G | G | G | |||||||||

| MP | A/duck/Mongolia/916/2018(H3N8) | 99.7% | A/northern pintail/Alaska/362/2013(H3N8) | 99.4% | |||||||||

| NS | A/duck/Bangladesh/37509/2019(H8N4) | 99.6% | A/duck/Bangladesh/37509/2019(H8N4) | 99.6% | G | G | Increased polymerase activity and virulence in mice | [32] | [57] | ||||

| PB1-F2 | N66S | S | S | N | N | N | N | Increased virulence in mice | [33] | [48] | |||

| PA | S37A | A | A | A | A | S | A | Increased polymerase activity in mammalian cell line | [34] | [58] | |||

| K142R | R | K | K | K | K | K | [30] | [55] | |||||

| N383D | D | D | D | D | D | D | Increased pathogenicity in ducks | [35] | [59] | ||||

| N409S | S | S | S | S | N | S | Increased polymerase activity in mammalian cell line | [34] | [58] | ||||

| NP | I41V | I | I | I | I | I | I | Increased polymerase activity in mammalian cell line | [36] | [60] | |||

| M105V | M | V | M | M | V | V | Increased virulence in chicken | [37] | [61] | ||||

| A184K | K | K | K | K | K | K | [38] | [62] | |||||

| F253I | I | I | I | I | I | I | Increased virulence in mice | [39] | [63] | ||||

| V286A | A | A | A | A | A | A | [40] | [64] | |||||

| M437T | T | T | T | T | T | T | |||||||

| NA | 69–73 deletion (QISNT) |

No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Increased virulence in mice | [41] | [65] | |||

| I117T | T | T | I | I | T | T | Increased resistance to antiviral drugs (oseltamivir and zanamivir) | [42] | [66] | ||||

| M1 | N30D | D | D | D | D | D | D | Increased virulence in mice | [25] | [50] | |||

| I43M | M | M | M | M | M | M | [43] | [67] | |||||

| T215A | A | A | A | A | A | A | [25] | [50] | |||||

| M2 | L26F | L | L | L | L | L | L | Increased resistance to antiviral drugs (amantadine and rimantadine) | [44] | [68] | |||

| S31N | S | S | S | S | N | S | [44] | [68] | |||||

| NS1 | P42S | S | S | S | S | S | S | Increased virulence in mice | [45] | [69] | |||

| D92E | D | D | D | D | D | D | Increased virulence in mice | [46] | [70] | ||||

| L103F | F | F | F | F | L | F | Increased replication and virulence in mice | [47] | [71] | ||||

| C138F | F | F | F | F | F | F | Increased replication in mammalian cell line | [48] | [72] | ||||

The amino acid mutations of the two H7 Korean AIVs were mostly similar, except for K142R in the PA gene of 20X-20 and M105V in the NP gene of 34X-2. The PA gene of the two H7 Korean AIVs was clustered in the same subgroup in the phylogenetic tree but showed a different amino acid mutation at the 142 position. The amino acid substitutions of E627K in the PB2 gene, known to increase virulence in mice and human adaptation markers, were observed in Jiangsu/1 but not in the two H7 Korean AIVs [24][49][46,47]. Additionally, the amino acid substitutions of I292V of the PB2 gene, which increase the polymerase activity in both and avian cells were not identified in the two H7 Korean AIVs. The amino acid substitutions of N66S in the PB1-F2 gene, which increased virulence in mice, were observed in the two H7 Korean AIVs compared to the chicken/1, which most recently caused human infections [33][48]. The other mutations related to the virulence of the virus and drug resistance are shown in Table 1.

3. Phylogenetic Analysis of H7 AIVs Isolates

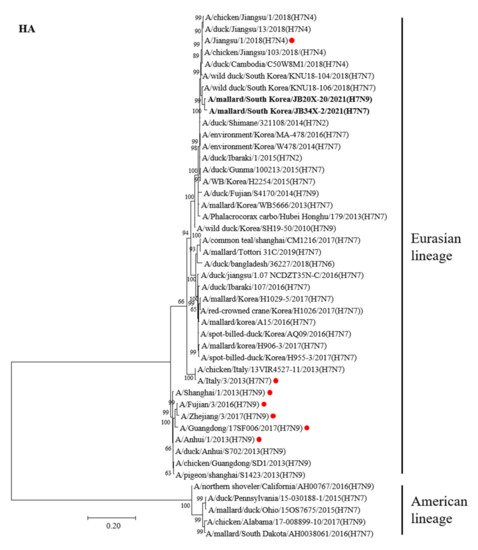

An ML tree analysis of the HA gene showed that the HA genes of 20X-20 and 34X-2 belonged to the Eurasian lineage (Figure 1). The HA genes of 20X-20 and 34X-2 showed 98.5% nucleotide identities with each other and were most closely related to A/wild duck/South Korea/KNU18-106/2018(H7N7), with identities of 97.8% and 98.5%, respectively (Table 2). Notably, the two H7 Korean AIVs showed high nucleotide similarity to the A/Jiangsu/1/2018(H7N4) virus (97.5% and 97%, respectively), which are human influenza viruses originating from AIVs. However, the HA genes of 20X-20 and 34X-2 viruses showed low nucleotide similarity to the HA gene of A/Italy/3/2013(H7N7) (90.2% each) and A/Anhui/1/2013(H7N9) (88.6% and 88.9%, respectively), which cause human infections.

Figure 1. Phylogenetic tree of the HA gene of the H7 avian influenza virus (AIV) nucleotides. The tree was analyzed using the maximum-likelihood (ML) method with 1000 bootstrap replication and only bootstrap values more than 50% are shown. The two H7 Korea AIVs isolated in this study are shown in bold. The human influenza viruses are indicated by red circles.

Table 2. Sequence identities of the A/mallard/South Korea/JB20X-20/2021 (20X-20) and A/mallard/South Korea/JB34X-2/2021 (34X-2) genome.

| Gene | 20X-20 | Genetic Identity | 34X-2 | Genetic Identity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PB2 | A/wild_duck/South_Korea/KNU18-106/2018(H7N7) | 98.3% |

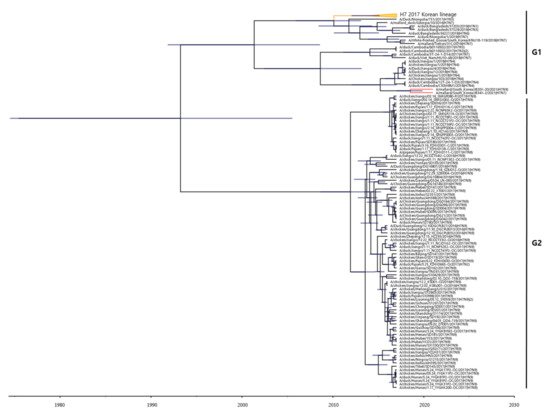

To estimate the times of origins of the HA gene of the two H7 Korean AIVs, the MCC tree was rewe reconstructed the MCC tree. As the HA gene of the two H7 Korean AIVs belonged to the Asian lineage, it was we reconstructed the MCC tree using the H7 gene of LPAIVs isolated between 2016 and 2021 in Asia. In the MCC tree analysis, HA genes formed two distinct genetic subgroups (G1 and G2) (Figure 2). The H7 LPAIV in the G1 subgroup was identified as the one circulating in South Korea in 2017, and the H7 LPAIVs in the G2 subgroup were closely related to the H7 LPAIV isolated in China between 2016 and 2017. The HA genes of 20X-20 and 34X-2 belonged to the G1 subgroup.

Figure 2. Maximum clade credibility (MCC) trees of the HA gene of H7 LPAIVs isolated between 2016 and 2021 in Asia. The MCC tree were constructed using the uncorrelated lognormal distribution relaxed clock method in BEAST v1.10.4. The ESS values were greater than 200. Posterior probabilities >0.8 are provided in the tree. The horizontal axis indicates the time scale, and the unit is 10 years. The two H7 Korean AIVs are shown in red. The H7 LPAIVs circulating in South Korea in 2017 are shown in orange.

The results of the phylogenetic tree of the NA gene showed that the NA gene of the two H7 Korean AIVs belonged to the Eurasian lineage (Supplementary Materials Figure S1). The NA genes of 20X-20 and 34X-2 showed the highest nucleotide identities with the NA gene of A/Anas platyrhynchos/South Korea/JB31/96/2019(H11N9) (98.2%) and A/mallard/Korea/A15/2016(H7N7) (97.4%), respectively. However, the NA gene of the two H7 Korean AIVs clustered distinct subgroups with human influenza viruses.

Most of the internal genes (PB2, PB1, PA, NP, M, and NS) of the two H7 Korean AIVs belonged to the Eurasian lineage, except for the M gene of 34X-2 (Supplementary Materials Figure S2). The PB2, PB1, PA, NP, M, and NS genes of 20X-20 and 34X-2 shared 95.1%. 95%, 96.7%, 94.1%, 93.9%, and 99.5% nucleotide identities, respectively. The NP and M genes, which showed less than 95% nucleotide similarity, were clustered into different subgroups. The PA gene of 20X-20 was clustered into the same subgroup as the PA gene of A/Mandarin duck/Korea/WB246/2016(H5N6), which is an internal gene of HPAIV.