Overall, transport consumes 94% of tourism-related energy use, compared to accommodation at 4%, and other activities at 2%. Almost 80% of tourism’s contribution to global warming is associated with leisure travel. In the near future, tourism will grow fast, and it seems necessary to introduce mechanisms to internalize leisure-travel-related CO2 emission costs, if climate change is to be managed. Drastic reductions in leisure travel would be needed to mitigate emissions worldwide. Excessive transport usage has led to high social costs and has caused a variety of negative externalities, such as traffic congestion; land consumption; accidents; air and noise pollution; destruction of the visual landscape; and waste in the use of resources such as raw materials, energy, and so on. However, tourism transport has become a crucial part of the tourism industry that generates substantial economic benefits worldwide. Therefore, the target should be to control the growth of tourism transport usage in order to make it environmentally sustainable, without compromising the ability of people to meet their need for mobility.

- sustainability

- road transport

- tourism activity

- carbon dioxide emission

1. Tourism Transport Energy Use

Overall, transport consumes 94% of tourism-related energy use, compared to accommodation at 4%, and other activities at 2% [1]. Almost 80% of tourism’s contribution to global warming is associated with leisure travel [1]. In the near future, tourism will grow fast, and it seems necessary to introduce mechanisms to internalize leisure-travel-related CO

emission costs, if climate change is to be managed. Drastic reductions in leisure travel would be needed to mitigate emissions worldwide. Excessive transport usage has led to high social costs and has caused a variety of negative externalities, such as traffic congestion; land consumption; accidents; air and noise pollution; destruction of the visual landscape; and waste in the use of resources such as raw materials, energy, and so on. However, tourism transport has become a crucial part of the tourism industry that generates substantial economic benefits worldwide. Therefore, the target should be to control the growth of tourism transport usage in order to make it environmentally sustainable, without compromising the ability of people to meet their need for mobility.

Road transport accounts for 81% of the total energy used by the transport sector [2]. The tourism road traffic segment is increasing rapidly without any sign of saturation. In addition, leisure traffic is highly correlated to private motorized vehicles [3]. In that sense, transport planning at tourist destinations should be focused on reducing private car usage for leisure purposes. However, the environmental impact of road transport related to tourism has been a neglected area of tourism transport research. Becken and Simmons [4] estimated that the contribution of private cars to tourism transport energy use at a West Coast tourist resort in New Zealand was about 79%. Dickinson et al. [5] found in Purbeck’s study that the car dominates (82%) as the modal choice in most European destinations; and that the bus was seen as the main alternative to the car, if improvements in the services had taken place in order to promote use.

Road transport is one of the most important factors responsible for air quality. In 2017, 23 out of 28 EU Member States’ air quality standards were still being exceeded—in more than 130 cities across Europe, in total—with NO

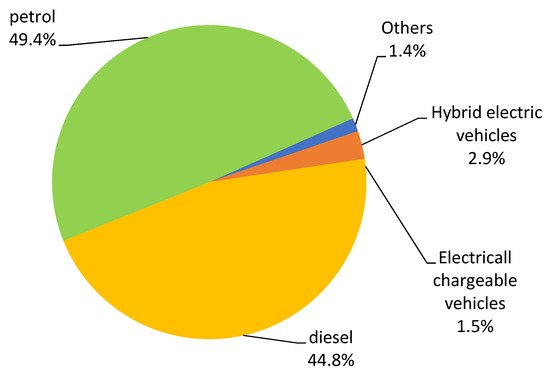

(nitrogen dioxide) and PM10 (particulate matter) the most problematic pollutants. Different policies have been adopted to regulate the situation, creating in some cases perverse effects due to the complexity of this issue. For this reason, the effect of the public policies on the sector are very important in economic and social terms. The economic valorization of emissions is outdated given the introduction of the electric vehicle; however, the widespread implementation of this type of vehicles will not be as widespread as may be believed, given the difficulties in logistics, facilities, price, etc. The pie chart (

) shows the new passenger cars (new registrations) in the EU15 countries by fuel type in percentage of categories in 2017. Some considerations in the pie chart become necessary. In the category Electrically Chargeable Vehicles are included battery electric vehicles (BEV), extended-range electric vehicles (EREV), plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEV), and fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEV). In the category Hybrid are included full and mild hybrids. In the category Others are included natural gas vehicles (NGV), LPG-fueled vehicles and ethanol (E85) vehicles [6].

New registration passenger car fleet by fuel type—EU15 countries in 2017. Source: ACEA.

Considering also the average age of the EU vehicle fleet, combustion vehicles will continue to have an important presence in the coming years, and the appearance of new technologies makes it necessary to review and improve the environmental policies in the sector to avoid possible perverse effects and optimize the transition to new and future technologies. As we can see, nowadays, we are still in a transition stage before new technologies can be applied in a general way. So, traditional public transport remains a good strategy for mitigation policy. This is clearer in the case of island destinations. The improvement of public transport services becomes more useful in terms of to mitigate pollutants and to facilitate tourist mobility at destinations. However, to foster more sustainable forms of tourist mobility, in the transition stage, some study becomes necessary to establish determinant variables of choosing transport mode at the destination. Gutiérrez and Miravet [7] point out that tourist mobility patterns at destinations depend on the socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of the tourist. Age, education level, social class, and country of origin affect their use of public transport.

2. Road Transport Emissions Mitigations Policy

Chapman (2007) [2] argues that fuel tax is a useful policy to curb road transport emissions. A fuel tax could be a more accurate approach, because a direct incentive on fuel efficiency arises that could encourage a modal shift. Storchmann [8] estimated the price elasticities for each mode of transport, and by motive for the trip. He found a high fuel price elasticity for leisure car travel (−0.120) compared to other reasons for traveling. He pointed out that travelers perceive car use as essential for work and business trips, but as unessential in the leisure segment. This means that if gasoline prices increase, using cars for leisure purpose tends to decrease. However, the implementation of a fuel tax for environmental purposes can be a hard task. According to the fuel price elasticity for leisure travel, there is a margin to try and shift from leisure car travel to a more sustainable mode of transport. Despite this, there are insurmountable difficulties. There are technical obstacles to implementing a leisure-related fuel tax. One is the fuel tax discrimination for the tourism segment. This means that a fuel tax applied to road usage for tourism-related activities would probably be impossible to apply, or it would incur high administrative costs.

Alternatively, the use of private cars to access tourism activities can be rationed by increasing passenger load factors (car sharing) or decreasing travel distance [1]. Forbidding the access of private cars with less than four travellers to National Parks could be a more reliable policy. Dickinson et al. (2009) [5] found there is some support for car restrictions and some willingness by visitors to use alternatives modes in rural tourist destinations. Thus, the focus is on minimizing the use of one particular mode of transport in favor of a more environmentally friendly one [9]. The latter study provides arguments for implementing new and attractive public transport supplies related to the leisure travel segment. Guiver et al [10] suggest that the rural tourism bus network needs to be reappraised by taking into account several attributes, such as social inclusion, traffic, and mileage reduction. The authors also point out that there are clear economic benefits associated with the development of an attractive bus network, which facilitates access opportunities for residents and visitors without cars. Moreover, there is evidence that identifies barriers to a modal shift from the private car to public transport alternatives. For instance, local residents do not want their car use restricted, and policies to achieve this modal shift have not succeeded [11]. Nevertheless, efforts must be made to allow for a more balanced use of the private car and public transport.

Following to Lumsdon [12] the provision of public transport in rural destinations is not usually sufficiently attractive to encourage any significant level of modal shift. The author emphasizes that it is necessary to find a new social construction for the bus travel model, where a multifaceted bus network plays an important role in encouraging people to enjoy their destination without a car. The case here is to choose between two design approaches. The former places the emphasis on the need to design a bus network to include tourism activities. The latter is a conventional approach that meets the needs of all users, but may be modified to accommodate the desires of tourists. A public transport service that provides a multifaceted service for residents without private cars and tourists, based on social inclusion, may improve social welfare; however, this approach shows also a trade-off between the need to serve a wide range of users and the reliability of services.

Alternatively, the introduction of the electric car could be a solution to mitigate emissions impacts on environment. However, the implementation of an electric car rental for tourism purposes requires high costs because an electric car has a short range (145–175 km) and this includes the cost of building a charging station in a rural zone. On the one hand, the cost of investment in the charging station depends on the cost of the station terminal and the length of the power cable. On the other hand, the sociodemographic features of the rural zone (e.g., population density and poor urbanization) could not justify such investment. Also, the optimal locations of such a docking station with charging system in areas with a low population density and high dispersion of habitats could be a serious difficulty to solve. In that sense, research about the assumption that the electric car could be an alternative to traditional transport for tourism in rural areas is not clear, despite technological advances [13].

3. Post-COVID-19 Stage

The post-COVID-19 pandemic stage perhaps provides an opportunity to adapt sustainability principles to transport for tourism [14]. Moreover, in the case of tourist destination mobility, there are two opposing forces in this process. On the one hand, the door-to-door feature of car transport helps us to avoid overcrowding. It creates a sense of safety in terms of limiting the spread of the virus, in contrast to collective transport. On the other hand, a sustainable mode of transport such as public road (collective) transport has been hit by the crisis and its offer reduced. Therefore, it seems that a change in tourist behavior to adopt a more sustainable transport mode is not clear-cut. However, in the post-COVID stage, the planning element is crucial to improve sustainability of transport for tourism at destinations. Local authorities can influence changes in tourist behavior through regulations that promote the development of sustainable tourism mobility at destination in consonance with COVID-restrictions. In that sense, the PASS study (Prepare-Protect-Provide-Avoid-Adjust Shift-Share Substitute-Stop) allows policymaking take into account for COVID-restrictions and, at the same time, to approach best practices in sustainable mobility [14].

As it was pointed out above, a multifaceted bus service can encourage tourists to use public transport at destinations more than private cars and, at the same time, serve a wide range of users, including rural area inhabitants. In addition, this transport model can also approach some of the environmental and social benefits of the sustainability requirements. Marek [14] emphasized that under post-COVID circumstances, the destination development model can point the way to adapt tourism transport policy to this new reality. He believes that more emphasis has to be placed on the possibility that the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic may transform tourist travel behavior in general and at destinations in particular. In that sense, the development of sustainable public transport policy at local level, generally well-developed in urban areas, has to be improved in rural areas to achieve social justice in terms of improving access to job opportunities, health care, and education. Therefore, it seems that the multifaceted bus service can offer more social and spatial justice. The challenge is to meet the requirements of COVID-19 and, at the same time, to promote the use of public transport. There is a need to research the adaptation elements.

References

- Gössling, S. Global environmental consequences of tourism. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2002, 12, 283–302.

- Chapman, L. Transport and climate change: A review. J. Transp. Geogr. 2007, 15, 354–367.

- Gronau, W.; Kagermeier, A. Key factors for successful leisure and tourism public transport provision. J. Transp. Geogr. 2007, 15, 127–135.

- Becken, S.; Simmons, D.G.; Frampton, C. Energy use associated with different travel choices. Tour. Manag. 2003, 24, 267–277.

- Dickinson, J.; Robbin, D.; Fletcher, J. Representation of transport: A rural destination analysis. Ann. Tour. Res. 2009, 36, 103–123.

- Directive 2008/50/EC. Policy Document: Ambient Air Quality and Cleaner Air for Europa 2008. 2019. Available online: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/ALL/?uri=CELEX:32008L0050 (accessed on 17 September 2021).

- Gutiérrez, A.; Miravet, D. The determinants of tourist use of public transport at the destination. Sustainability 2016, 8, 908.

- Storchmann, K.-H. The impact of fuel taxes on public transport—An empirical assessment for Germany. Transp. Policy 2001, 8, 19–28.

- Verbeek, D.; Mommaas, H. Transitions to sustainable mobility: The social practices approach. J. Sustain. Tour. 2008, 16, 629–644.

- Guiver, J.; Lumsdon, L.; Weston, R.; Ferguson, M. Do buses help meet tourism objectives? The contribution and potential of scheduled buses in rural destination areas. Transp. Policy 2007, 14, 275–282.

- Robbins, D.; Dickinson, J. Can domestic tourism growth and reduced car dependency be achieved simultaneously in the UK? In Tourism and Climate Change Mitigation: Methods, Greenhouse. Gas Reductions and Policies; Peeters, P., Ed.; Stichting NHTV Breda: Breda, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 169–188.

- Lumsdon, L.M. Factors affecting the design of tourism bus services. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 33, 748–766.

- Szymańska, E.; Panfiluk, E.; Kiryluk, H. Innovative solutions for the development of sustainable transport and improvement of the tourist accessibility of peripheral areas: The case of the Białowieża forest region. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2381.

- Marek, W. Will the consequences of COVID-19 trigger a redefining of the role of transport in the development of sustainable tourism? Sustainability 2021, 13, 1887.