Acne inversa, namely, Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), is a chronic inflammatory skin disease affecting ~1% of the global population. HS typically occurs after puberty, with the average age of onset in the second or third decades of life and with a female predominance. Approximately one third of patients are genetically predisposed. Moreover, lifestyle factors, such as smoking and obesity, play a crucial role in the clinical course of HS.

- hidradenitis suppurativa

- diagnosis

- pathogenesis

- treatments

- translational studies

1. Introduction

Due to its chronic nature and frequently occurring relapses, HS has a great impact on the patients’ quality of life, deeply affecting social, working, and psychological aspects [1][2][3][4]. Therefore, early diagnosis is very important for HS patients in order to ensure the best possible course of this stigmatizing and painful disease.

1.1. Clinical Aspects

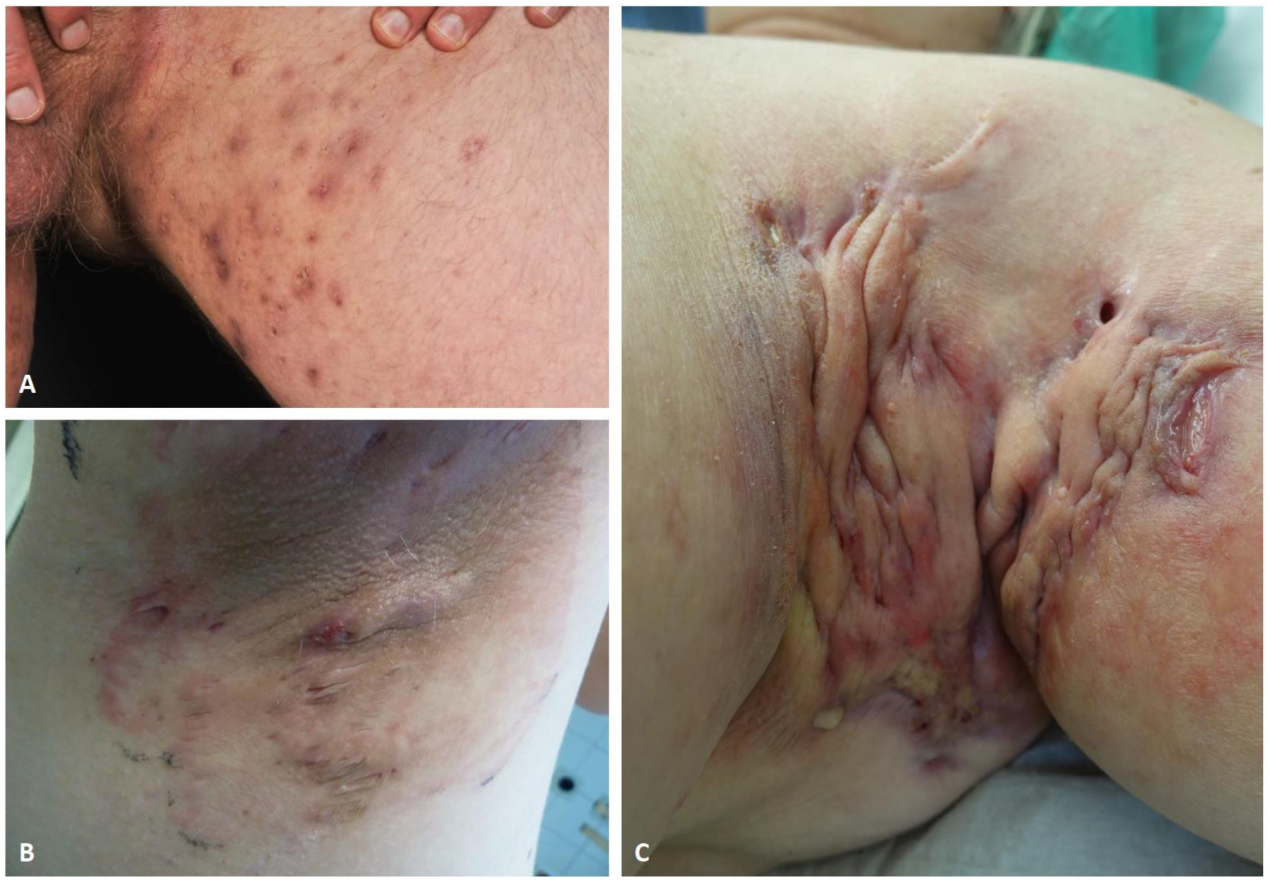

HS is usually localized in the apocrine gland-bearing areas ( Figure 1 ). According to the modified Dessau definition, three diagnostic criteria should be matched: presence of typical lesions, typical locations, and chronicity [5]. Deep-seated painful nodules, abscesses, suppurative sinus tracts or tunnels, bridged scars, and double- and multi-ended comedones (also known as “tombstone comedones”) are described as typical lesions. Commonly, patients experience pain, malodor, a burning sensation, and an itch [6]. Chronicity, defined as two recurrences within the period of six months, is based on a complex pathogenesis underlying the disease; nodules and abscesses can rupture, bleed, and produce purulent discharge. The role of bacteria, infections, and superinfections in HS is still debated and controversial, but they probably have a role in promoting the chronicity of HS [7]. The persistence of the pathology entails the occurrence of dermal contracture and fibrosis of lesional skin. Intertriginous anatomic locations are typically involved, particularly the axillary, infra- and intermammary, inguinal, perineal, perianal, and gluteal regions [8].

HS may less frequently occur in the lower abdomen, suprapubic, retroauricular, nape, eyelids, and scalp [9][10]. Since diagnosis of HS may typically be delayed for years, in order to enhance a correct diagnosis, other factors should be investigated; above all, a family history of HS and history of other follicular occlusion diseases [11]. Moreover, the identification of pathogenic microbes should be evaluated and it could be useful in the therapeutic management, even if a primary infection is not the principal cause of HS [12]. Considering the lack of knowledge to date on the exact pathogenetic mechanism underlying the onset of HS, the phenotypic variants available today still receive criticisms and proposals for change. Three clinical subtypes of HS have been described: axillary-mammary, follicular, and gluteal [13]. According to another classification by van der Zee et al. [14], there are six phenotypes of HS: (i) regular type; (ii) frictional furuncle type; (iii) scarring folliculitis type; (iv) conglobata type; (v) syndromic type; and (vi) ectopic type. Recently, it was suggested to distinguish between a follicular subtype and an inflammatory phenotype, which is usually associated with a worse course of HS [15].

Figure 1. Clinical images of typical HS lesions in groin (A), and axilla (B,C). Superficial papules, small abscesses without scarring or sinus tracts, Hurley stage I (A). Multiple, recurrent abscesses with initial sinus tracts and cicatrization, Hurley stage II (B). Diffuse involvement of the axillary region with large abscesses, interconnected tracts, and scarring, Hurley stage III (C).

1.2. Severity Assessment

The first severity classification of HS was proposed by Hurley in 1989, categorizing patients into three stages based mainly on the presence of sinus tracts and scarring. The Hurley scoring system is a simple tool, nevertheless it is non-quantitative and static. Indeed, the use of this method in clinical studies may have significant limitations [16]. A more complex and detailed severity scoring method, called the Sartorius Scoring system, better suited to assess disease severity and grade of inflammation, was later proposed. Even though it is more accurate and precise in defining the severity of the disease, the Sartorius score may be time-consuming in routine clinical practice. Still today, the Hurley staging and the Sartorius scoring, together with HS Physician Global Assessment systems are the most commonly used assessment tools [17][18]. In addition, the HS Clinical Response (HiSCR), defined as the reduction in at least 50% of total abscess and inflammatory nodule count, with no increase in abscess count and no increase in draining fistula count relative to baseline, is used mainly to assess treatment effects in trials [19]. Recently, several other clinical measures for assessing HS disease severity were described, including the recently proposed HS Severity Score System (IHS4), the Acne Inversa Severity Index, and the Severity Assessment of HS score, which need further validation [20][21][22]. Ultrasound (US) aids in the diagnosis and assessment of HS disease severity [23]. Different subclinical lesions have been identified and categorized using US, and their recognition is able to modify a therapeutic approach [24]. Wortsman and colleagues proposed a sonographic scoring system for HS (SOS-HS) that combined the results of parameters included in Hurley’s classification with the relevant sonographic findings [23]. Finally, it is well known how HS may have a significant impairment of patients’ quality of life (QoL). Therefore, specific QoL tools have been developed and validated for HS: HiSQOL [25], HSQoL-24 [26], and patient-reported outcome (PRO) questionnaires [27]. Recently, a new graphical tool able to better describe HS burden, the so-called HIDRAdisk, has been introduced [28][29].

2. Future Treatments and Personalized Therapies

| Intervention/Compound | Target | Type | Phase | Number of Studies | ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avacopan | C5a receptor | Systemic drug | 2 | 1 | NCT03852472 |

| Bimekizumab | IL-17A, IL-17F | Systemic drug | 3 | 2 | NCT04242446, NCT04242498 |

| Iscalimab (CFZ533), LYS006 | CD40, LTA4H (respectively) |

Systemic drug | 2 | 1 | NCT03827798 |

| CSL324 | G-CSF receptor | Systemic drug | 1 | 1 | NCT03972280 |

| Imsidolimab | IL-36 receptor | Systemic drug | 2 | 1 | NCT04856930 |

| INCB05470 | JAK-1 | Systemic drug | 2 | 1 | NCT04476043 |

| KT-474 | IRAK4 | Systemic drug | 1 | 1 | NCT04772885 |

| LY3041658 | ELR + CXC chemokines | Systemic drug | 2 | 1 | NCT04493502 |

| Metformin | unknown (anti-inflammatory) | Systemic drug | 3 | 1 | NCT04649502 |

| PF-06650833, PF-06700841, PF-06826647 |

IRAK4, TYK2+JAK1, TYK2 (respectively) |

Systemic drug | 2 | 1 | NCT04092452 |

| Risankizumab | IL-23p19 | Systemic drug | 2 | 1 | NCT03926169 |

| Secukinumab | IL-17A | Systemic drug | 3 | 3 | NCT04179175, NCT03713619, NCT03713632 |

| Spesolimab | IL-36 receptor | Systemic drug | 2 | 2 | NCT04876391, NCT04762277 |

| Tofacitinib | pan-JAK | Systemic drug | 2 | 1 | NCT04246372 |

| Upadacitinib | JAK-1 | Systemic drug | 2 | 1 | NCT04430855 |

| Local therapy (wound dressings, creams, gels, sclerotherapy, AMP, triamcinolone) | Local therapy | all | 9 | NCT04648631, NCT04194541, NCT04388163, NCT04354012, NCT04541550, NCT02805595, NCT04582669, NCT04756336, NCT04414514 | |

| Laser treatment | Laser | n.a. | 2 | NCT04508374, NCT03054155 | |

| Surgery (different procedures +/−ADA or NPWT+/−i) | Surgery | n.a. | 4 | NCT04526561, NCT04325607, NCT03784313, NCT03221621 | |

| Other (acupuncture, HS management, electronic reporting) | Other | n.a./4 | 3 | NCT04218422, NCT04200690, NCT04132388 |

3. Conclusions

References

- Napolitano, M.; Megna, M.; Timoshchuk, E.A.; Patruno, C.; Balato, N.; Fabbrocini, G.; Monfrecola, G. Hidradenitis suppurativa: From pathogenesis to diagnosis and treatment. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2017, 10, 105–115.

- Chernyshov, P.V.; Finlay, A.Y.; Tomas-Aragones, L.; Poot, F.; Sampogna, F.; Marron, S.E.; Zemskov, S.V.; Abeni, D.; Tzellos, T.; Szepietowski, J.C.; et al. Quality of Life in Hidradenitis Suppurativa: An Update. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6131.

- Weigelt, M.A.; Milrad, S.F.; Kirby, J.R.S.; Lev-Tov, H. Psychosocial impact of hidradenitis suppurativa: A practical guide for clinicians. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2021, 14, 1–23.

- Montero-Vilchez, T.; Diaz-Calvillo, P.; Rodriguez-Pozo, J.A.; Cuenca-Barrales, C.; Martinez-Lopez, A.; Arias-Santiago, S.; Molina-Leyva, A. The Burden of Hidradenitis Suppurativa Signs and Symptoms in Quality of Life: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6709.

- Revuz, J. Hidradenitis suppurativa. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2009, 23, 985–998.

- Lipsker, D.; Severac, F.; Freysz, M.; Sauleau, E.; Boer, J.; Emtestam, L.; Matusiak, Ł.; Prens, E.; Velter, C.; Lenormand, C.; et al. The ABC of Hidradenitis Suppurativa: A Validated Glossary on how to Name Lesions. Dermatology 2016, 232, 137–142.

- Marasca, C.; Tranchini, P.; Marino, V.; Annunziata, M.C.; Napolitano, M.; Fattore, D.; Fabbrocini, G. The pharmacology of antibiotic therapy in hidradenitis suppurativa. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020, 13, 521–530.

- Revuz, J.E.; Jemec, G.B.E. Diagnosing Hidradenitis Suppurativa. Dermatol. Clin. 2016, 34, 1–5.

- Agut-Busquet, E.; Romaní, J.; Ribera, M.; Luelmo, J. Hidradenitis suppurativa of the nape: Description of an atypical phenotype related to severe early-onset disease in men. J. Dermatol. 2019, 46, 149–153.

- Esmann, S.; Dufour, D.N.; Jemec, G.B. Questionnaire-based diagnosis of hidradenitis suppurativa: Specificity, sensitivity and positive predictive value of specific diagnostic questions. Br. J. Dermatol. 2010, 163, 102–106.

- Bettoli, V.; Pasquinucci, S.; Caracciolo, S.; Piccolo, D.; Cazzaniga, S.; Fantini, F.; Binello, L.; Pintori, G.; Naldi, L. The Hidradenitis suppurativa patient journey in Italy: Current status, unmet needs and opportunities. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2016, 30, 1965–1970.

- Bettoli, V.; Manfredini, M.; Massoli, L.; Carillo, C.; Barozzi, A.; Amendolagine, G.; Ruina, G.; Musmeci, D.; Libanore, M.; Curtolo, A.; et al. Rates of antibiotic resistance/sensitivity in bacterial cultures of hidradenitis suppurativa patients. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2019, 33, 930–936.

- Canoui-Poitrine, F.; Le Thuaut, A.; Revuz, J.E.; Viallette, C.; Gabison, G.; Poli, F.; Pouget, F.; Wolkenstein, P.; Bastuji-Garin, S. Identification of three hidradenitis suppurativa phenotypes: Latent class analysis of a cross-sectional study. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2013, 133, 1506–1511.

- van der Zee, H.H.; Jemec, G.B. New insights into the diagnosis of hidradenitis suppurativa: Clinical presentations and phenotypes. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2015, 73, S23–S26.

- Martorell, A.; Jfri, A.; Koster, S.B.L.; Gomez-Palencia, P.; Solera, M.; Alfaro-Rubio, A.; Hueso, L.; Sanz-Motilva, V. Defining hidradenitis suppurativa phenotypes based on the elementary lesion pattern: Results of a prospective study. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2020, 34, 1309–1318.

- Thorlacius, L. Severity staging of hidradenitis suppurativa: Is Hurley classification the answer? Br. J. Dermatol. 2019, 181, 243–244.

- Sartorius, K.; Emtestam, L.; Jemec, G.B.E.; Lapins, J. Objective scoring of hidradenitis suppurativa reflecting the role of tobacco smoking and obesity. Br. J. Dermatol. 2009, 161, 831–839.

- Sartorius, K.; Killasli, H.; Heilborn, J.; Jemec, G.B.E.; Lapins, J.; Emtestam, L. Interobserver variability of clinical scores in hidradenitis suppurativa is low: Hidradenitis suppurativa scoring variability. Br. J. Dermatol. 2010, 162, 1261–1268.

- Kimball, A.B.; Sobell, J.M.; Zouboulis, C.C.; Gu, Y.; Williams, D.A.; Sundaram, M.; Teixeira, H.D.; Jemec, G.B. HiSCR (Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response): A novel clinical endpoint to evaluate therapeutic outcomes in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa from the placebo-controlled portion of a phase 2 adalimumab study. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2016, 30, 989–994.

- Chiricozzi, A.; Faleri, S.; Franceschini, C.; Caro, R.D.; Chimenti, S.; Bianchi, L. AISI: A New Disease Severity Assessment Tool for Hidradenitis Suppurativa. Wounds 2015, 27, 258–264.

- Zouboulis, C.C.; Tzellos, T.; Kyrgidis, A.; Jemec, G.B.E.; Bechara, F.G.; Giamarellos-Bourboulis, E.J.; Ingram, J.R.; Kanni, T.; Karagiannidis, I.; Martorell, A.; et al. Development and validation of the International Hidradenitis Suppurativa Severity Score System (IHS4), a novel dynamic scoring system to assess HS severity. Br. J. Dermatol. 2017, 177, 1401–1409.

- Hessam, S.; Scholl, L.; Sand, M.; Schmitz, L.; Reitenbach, S.; Bechara, F.G. A Novel Severity Assessment Scoring System for Hidradenitis Suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2018, 154, 330–335.

- Wortsman, X.; Moreno, C.; Soto, R.; Arellano, J.; Pezo, C.; Wortsman, J. Ultrasound in-depth characterization and staging of hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol. Surg. 2013, 39, 1835–1842.

- Marasca, C.; Marasca, D.; Megna, M.; Annunziata, M.C.; Fabbrocini, G. Ultrasound: An indispensable tool to evaluate the outcome of surgical approaches in patients affected by hidradenitis suppurativa. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2020, 34, e413–e414.

- Kirby, J.; Thorlacius, L.; Villumsen, B.; Ingram, J.; Garg, A.; Christensen, K.; Butt, M.; Esmann, S.; Tan, J.; Jemec, G. The Hidradenitis Suppurativa Quality of Life (HiSQOL) score: Development and validation of a measure for clinical trials. Br. J. Dermatol. 2019, 183, 340–348.

- Marrón, S.; Gómez-Barrera, M.; Aragonés, L.T.; Díaz, R.D.; Rull, E.V.; Álvarez, M.M.; Puig, L. Development and Preliminary Validation of the HSQoL-24 Tool to Assess Quality of Life in Patients with Hidradenitis Suppurativa. Actas Dermo-Sifiliogr. 2019, 110, 554–560.

- Kimball, A.B.; Sundaram, M.; Banderas, B.; Foley, C.; Shields, A.L. Development and initial psychometric evaluation of patient-reported outcome questionnaires to evaluate the symptoms and impact of hidradenitis suppurativa. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2018, 29, 152–164.

- Chiricozzi, A.; Bettoli, V.; De Pità, O.; Dini, V.; Fabbrocini, G.; Monfrecola, G.; Musumeci, M.; Parodi, A.; Sampogna, F.; Pennella, A.; et al. HIDRAdisk: An innovative visual tool to assess the burden of hidradenitis suppurativa. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2018, 33, e24–e26.

- Fabbrocini, G.; Marasca, C.; Megna, M.; Peris, K.; HS Quality of Life Study Group. Age and gender influence on HIDRAdisk outcomes in adalimumab-treated hidradenitis suppurativa patients. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2019, 33, 25–27.

- van Straalen, K.R.; Schneider-Burrus, S.; Prens, E.P. Current and future treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa. Br. J. Dermatol. 2020, 183, e178–e187.

- Zouboulis, C.C.; Frew, J.W.; Giamarellos-Bourboulis, E.J.; Jemec, G.B.E.; Del Marmol, V.; Marzano, A.V.; Nikolakis, G.; Sayed, C.J.; Tzellos, T.; Wolk, K.; et al. Target molecules for future hidradenitis suppurativa treatment. Exp. Dermatol. 2021, 30, 8–17.

- Marasca, C.; Megna, M.; Balato, A.; Balato, N.; Napolitano, M.; Fabbrocini, G. Secukinumab and hidradenitis suppurativa: Friends or foes? JAAD Case Rep. 2019, 5, 184–187.

- Ribero, S.; Ramondetta, A.; Fabbrocini, G.; Bettoli, V.; Potenza, C.; Chiricozzi, A.; Licciardello, M.; Marzano, A.V.; Bianchi, L.; Rozzo, G.; et al. Effectiveness of Secukinumab in the treatment of moderate-severe hidradenitis suppurativa: Results from an Italian multicentric retrospective study in a real-life setting. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2021, 35, e441–e442.

- Kerdel, F.R.; Azevedo, F.A.; Kerdel Don, C.; Don, F.A.; Fabbrocini, G.; Kerdel, F.A. Apremilast for the Treatment of Mild-to-Moderate Hidradenitis Suppurativa in a Prospective, Open-Label, Phase 2 Study. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2019, 18, 170–176.

- Folkes, A.S.; Hawatmeh, F.Z.; Wong, A.; Kerdel, F.A. Emerging drugs for the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa. Expert Opin. Emerg. Drugs 2020, 25, 201–211.

- Holm, J.G.; Jørgensen, A.R.; Yao, Y.; Thomsen, S.F. Certolizumab pegol for hidradenitis suppurativa: Case report and literature review. Dermatol. Ther. 2020, 2, e14494.

- Wohlmuth-Wieser, I.; Alhusayen, R. Treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa with certolizumab pegol during pregnancy. Int. J. Dermatol. 2020, 60, e140–e141.

- Esme, P.; Akoglu, G.; Caliskan, E. Rapid Response to Certolizumab Pegol in Hidradenitis Suppurativa: A Case Report. Skin Appendage Disord. 2021, 7, 58–61.

- Kok, Y.; Nicolopoulos, J.; Dolianitis, C. Tildrakizumab as a potential long-term therapeutic agent for severe Hidradenitis Suppurativa: A 15 months experience of an Australian institution. Australas. J. Dermatol. 2021, 62, e313–e316.

- Megna, M.; Ruggiero, A.; Di Guida, A.; Patrì, A.; Fabbrocini, G.; Marasca, C. Ixekizumab: An efficacious treatment for both psoriasis and hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol. Ther. 2020, 33, e13756.

- Yoshida, Y.; Oyama, N.; Iino, S.; Shimizu, C.; Hasegawa, M. Long-standing refractory hidradenitis suppurativa responded to a brodalumab monotherapy in a patient with psoriasis: A possible involvement of Th17 across the spectrum of both diseases. J. Dermatol. 2021, 48, 916–920.

- Tricarico, P.M.; Boniotto, M.; Genovese, G.; Zouboulis, C.C.; Marzano, A.V.; Crovella, S. An Integrated Approach to Unravel Hidradenitis Suppurativa Etiopathogenesis. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 892.