Review of the effect of COVID-19 on pulmonary circulation

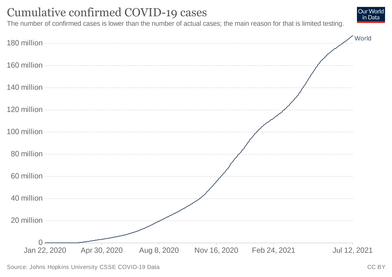

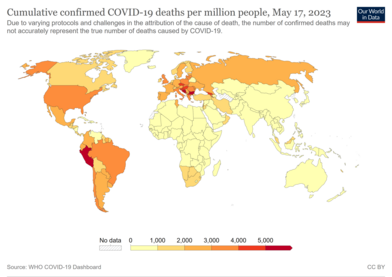

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an infectious disease caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). It was first identified in December 2019 in Wuhan, Hubei, China, and has resulted in an ongoing pandemic. The first confirmed case has been traced back to 17 November 2019 in Hubei. As of 30 December 2021, more than 285 million cases have been reported across countries and territories, resulting in more than 5.42 million deaths. More than people have recovered. Common symptoms include fever, cough, fatigue, shortness of breath, and loss of smell and taste. While the majority of cases result in mild symptoms, some progress to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) possibly precipitated by cytokine storm, multi-organ failure, septic shock, and blood clots. The time from exposure to onset of symptoms is typically around five days, but may range from two to fourteen days. The virus is primarily spread between people during close contact,[lower-alpha 1] most often via small droplets produced by coughing,[lower-alpha 2] sneezing, and talking. The droplets usually fall to the ground or onto surfaces rather than travelling through air over long distances. Transmission may also occur through smaller droplets that are able to stay suspended in the air for longer periods of time. Less commonly, people may become infected by touching a contaminated surface and then touching their face. It is most contagious during the first three days after the onset of symptoms, although spread is possible before symptoms appear, and from people who do not show symptoms. The standard method of diagnosis is by real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) from a nasopharyngeal swab. Chest CT imaging may also be helpful for diagnosis in individuals where there is a high suspicion of infection based on symptoms and risk factors; however, guidelines do not recommend using CT imaging for routine screening. Recommended measures to prevent infection include frequent hand washing, maintaining physical distance from others (especially from those with symptoms), quarantine (especially for those with symptoms), covering coughs, and keeping unwashed hands away from the face. The use of cloth face coverings such as a scarf or a bandana has been recommended by health officials in public settings to minimise the risk of transmissions, with some authorities requiring their use. Health officials also stated that medical-grade face masks, such as N95 masks, should only be used by healthcare workers, first responders, and those who directly care for infected individuals. There are no vaccines nor specific antiviral treatments for COVID-19. Management involves the treatment of symptoms, supportive care, isolation, and experimental measures. The World Health Organization (WHO) declared the COVID‑19 outbreak a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) on 30 January 2020 and a pandemic on 11 March 2020. Local transmission of the disease has occurred in most countries across all six WHO regions. thumb|thumbtime=0:02|upright=1.4|Video summary (script)- Pulmonary arterial hypertension

- chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension

- COVID-19

- pulmonary circulation

1. Introduction

The coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) is an infectious disease that emerged in the Chinese city of Wuhan in December 2019 [1] and rapidly extended worldwide, leading to its declaration as a pandemic disease by the World Health Organization on 11 March 2020 [2]. By 30 June 2020, the rapid spread of the virus has caused more than 10,000,000 cases and more than 500,000 deaths all over the world (source: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/).

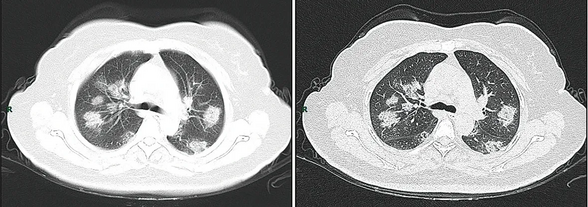

COVID-19 is caused by the severe acute respiratory coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV2), an RNA virus of the family Coronaviridae. Common symptoms include fever, cough, sore throat, and dyspnea [1][3], while the most severe cases develop pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARSD), requiring admission to the intensive care unit in up to 20% of hospitalized patients [4]. Reported data suggest an overall mortality rate ranging from 0.3 per 1000 cases in patients aged under 18 to 305 per 1000 cases in elderly people (>85-year-old) [4].

Precapillary pulmonary hypertension (PH) includes a variety of diseases leading to increased pulmonary artery pressure (≥25 mmHg) in the presence of normal pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (<15 mmHg) and a pulmonary vascular resistance >3 Wood units at rest [5]. Among them, pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) constitute a particular group due to its relation to poor quality of life and shortened survival [6]:

-

PAH is a rare, noncurable disease characterized by an aberrant pulmonary vascular remodeling that may be either idiopathic or related to different clinical conditions [6]. PAH-related histological changes include endothelial damage and dysfunction, vasoconstriction, vascular cell proliferation leading to vascular obliteration and wall thickening, and, eventually, to the formation of plexiform lesions [7]. Furthermore, there is a marked component of perivascular inflammation and microthrombosis [8].

-

CTEPH constitutes a different group of precapillary PH secondary to the obstruction of the pulmonary arteries by organized thrombus after a pulmonary embolism. These pulmonary vascular changes induce small-vessel vasculopathy consisting of altered vascular remodeling initiated or potentiated by a combination of defective angiogenesis, impaired fibrinolysis, and endothelial dysfunction [9].

The resultant increased pulmonary arterial pressures in PAH and CTEPH contribute to a further increase of the right ventricular afterload, thus leading to right ventricular dysfunction and reducing survival among affected patients, being heart failure the most common cause of death [10]. Hospitalizations for cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular diseases are common in these groups of patients and carry a high mortality risk, being especially high in patients admitted to the intensive care unit [11][12].

Patients with previous cardiovascular risk factors or a cardiovascular disease seem to be at a higher risk of developing severe forms of SARS-CoV-2, with higher rates of mortality described in this population [1][13][14]. Moreover, the shortage of equipment needed to care for critically ill patients in some areas has led to difficult decisions, and the patient’s short-term likelihood of surviving the acute medical episode has remained the rationale for rationing. As physicians, bearing this reality in mind, it seemed straightforward to assume that PAH and CTEPH patients were at a higher risk of developing severe forms of the disease and that their chances of recovering from such an insult were scarce.

Noteworthy, some case-series have repeatedly presented the unexpected favorable outcome of COVID-19 infection in this population, suggesting that these patients could be somehow protected against severe forms of the disease [15][16][17]. However, whether this protection is due to receiving therapy, to their special awareness about their particular risk factor or any other physiological condition related to the disease is still a remaining question.

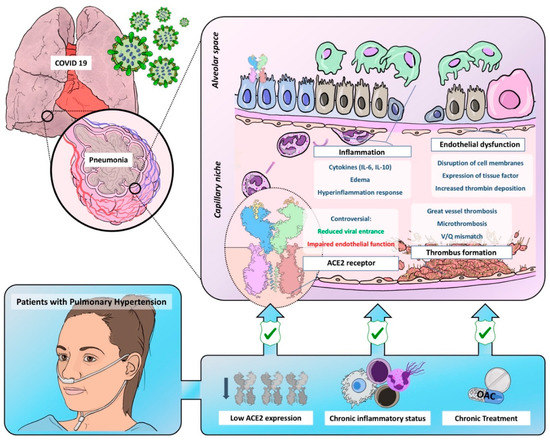

With this comprehensive review, we aim to describe the effects of SARS-COV-2 in the pulmonary circulation and the possible differential features in patients exhibiting pulmonary microvasculopathy, such as PAH and CTEPH patients, since we believe it will help to further understand COVID-19 and its pulmonary consequences ((Figure 1).

Figure 1. Graphic representation of common pathobiological characteristics between Coronavirus Disease of 2019 and pulmonary hypertension and the possible mechanisms leading to reduced virulence and severity in this population. ACE2 = angiotensin-converter enzyme 2; OAC = oral anticoagulant.

2. Endothelial dysfunction, inflammatory response, and thrombosis in COVID-19

Severe COVID-19 is characterized by a disproportional inflammatory response to an initial acute lung insult, which aggravates the lung injury and leads to a severe hypoxemic respiratory failure and, ultimately, to death [18][19][20][21][22][23]. Thus, in severe cases, the initial adaptive immune response necessary to eliminate the virus is followed by a severe and persistent inflammatory reaction, which appears to govern the clinical picture at this point, leading to further lung destruction and, therefore, ARDS. This exaggerated inflammation is mediated by several cytokines (IL-6, IL10, TNF-α, INF-γ), as well as mononuclear cells and neutrophils [18][19]. IL-6 is the central element of this cytokine storm by stimulating the expression of other cytokines and promoting edema [20]. The level of cytokines is higher in those patients who require admission to intensive care units in whom their lymphocyte count is lower. This finding suggests that the low absolute lymphocyte count observed in COVID-19 patients could be a consequence of the high serum cytokines concentrations that negatively regulate T-cell survival and proliferation [21]. Furthermore, T cells in COVID-19 express high levels of programmed cell death-1, an indicator of T-cell exhaustion [21]. Thus, it seems that the severe clinical picture described in COVID-19 patients is mediated by this inflammatory response responsible for both lung injury and impaired cellular immunity, which hampers the fight against the viral infection [21].

This immune response to the SARS-Cov-2 infection is more severe than that produced in other viral infections [22]. Older patients and those with previous comorbidities, which may present a chronic subclinical inflammatory status, could be at a higher risk of developing this cytokine storm. This could explain, at least in part, the worse prognosis described in these groups [14][22][23].

On histology, the lungs of COVID-19 patients present diffuse alveolar damage with “necrosis of alveolar lining cells, pneumocyte type 2 hyperplasia, and linear intra-alveolar fibrin deposition” [24]. The inflammatory infiltrates described in COVID-19 lungs differs from that described in H1N1 influenza lungs, with a predominant infiltration of CD4-positive T cells and a lower number of CD8-positive T cells and neutrophils in COVID-19 lungs [24]. Furthermore, there is also an extensive macrophagic infiltration contributing to the alveolar damage [25]

These inflammatory and the above-described procoagulant statuses are not isolated phenomena. The mechanisms leading to the activation of a coagulation cascade in COVID-19 are not well-defined but seem to be related to the inflammatory response also responsible for the endothelial damage and include the releasing of procoagulant factors [18][26]. COVID-19 pneumonia has some clinical, analytic, and histological similarities with macrophage activation syndrome (MAS), including the cytokine storm and high ferritin levels [25][27]. This is the rationale for the use of anti-cytokine therapies and corticosteroids in severe COVID-19 patients [27][28][29][30]. This MAS-like inflammatory response triggers the expression of the active tissue factor, which leads to a massive coagulation cascade activation, with the ulterior development of thrombotic events and widespread pulmonary microangiopathy [25]. These endothelial damages and coagulation activations are enhanced by local hypoxia constituting a deleterious vicious circle [25][31].

Furthermore, the detection of serum marker-specific neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) in COVID-19 patients suggests a pivotal role of these structures in the marked inflammatory and prothrombotic responses. NETs are extracellular webs of chromatin, microbicidal proteins, and oxidative agents released by neutrophils to contain infections. The uncontrolled release of NETs leads to a procoagulant status and widespread inflammation [32]. Thus, an increased neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is related to a severe COVID-19 course due to a disproportionate innate immune response leading to the release of cytokines and inflammatory infiltrates with tissue necrosis [33].

Thus, it seems that severe ARDS and widespread thrombosis are complementary phenomena leading to the severe clinical course described in COVID-19 patients [24].

3. Pulmonary Hypertension: A Paradigm of Endothelial Dysfunction

We have described how SARS-Cov-2 has an affinity for endothelial cells affecting not only pulmonary circulation but to other vascular territories (heart, gut, brain, and kidney). This becomes even more evident in patients with previous endothelial dysfunctions, such as hypertension or diabetes mellitus [18].

Endothelial dysfunction is one of the most relevant hallmarks and a critical contributor determining the onset and progression of PH. Pulmonary vascular endothelium controls the blood barrier integrity, the vascular tone by producing vasodilator and vasoconstrictor molecules and, also, optimizes the gas exchange in different conditions, being the main player in maintaining the vasomotor balance and vascular-tissue homeostasis. Also, the integrity of the endothelial barrier is essential for controlling an inflammatory and thrombosis-free surface. Therefore, an alteration of the endothelium leads to a pro-edematous, pro-vasoconstriction, prothrombotic and proinflammatory phenotype, which eventually alters the cell metabolism and oxidative stress, leading to a pro-proliferative and antiapoptotic phenotype all responsible in the last instance of the PH phenotype [24][34][35].

Pulmonary vascular remodeling in PAH and CTEPH is not only caused by the proliferation of different cells in the arterial wall but by the loss of precapillary arteries and by a severe chronic perivascular inflammatory infiltrate [8]. These conditions constitute a paradigm of endothelial dysfunction with a propensity to vasoconstriction; thrombosis; the production of reactive oxygen species; the expression of adhesion molecules (E-selectin, ICAM-1 and VCAM-1) and a massive release of cytokines and growth factors [8]. Thus, a devastating effect of COVID-19 would be expectable in these patients.

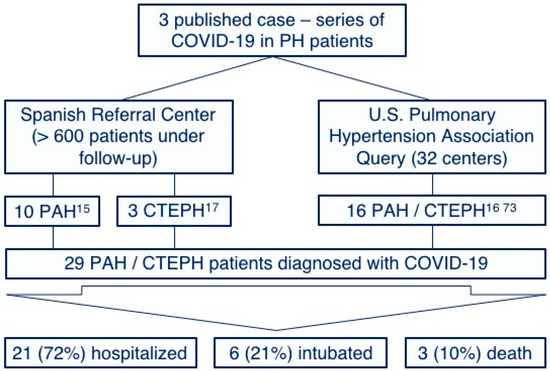

Few cases of COVID-19 in PAH and CTEPH patients have been reported. This observation may be explained by the low prevalence of these diseases and by the increased awareness of chronic patients with a special emphasis on social-distancing measure compliances [36][37]. However, we have recently published our surprisingly positive experience with COVID-19 in our PAH [15] and CPTEH [17] populations without any of them requiring intensive care and any deaths reported. Furthermore, a similar benign course has been observed in other centers [16][38], with no published reports suggesting particularly adverse outcomes [39] (Figure 2). Although the proportion of patients requiring intubation is similar to that described for the global COVID-19 population [4], it must be highlighted that these case-series represent a very biased population constituted only by those symptomatic patients who required hospitalization. We hypothesize that a high proportion of PAH and CTEPH patients infected by SARS-Cov-2 might have developed a mild or even an asymptomatic course and were not tested for SARS-Cov-2. Thus, the low prevalence of COVID-19 in PH patients might also be explained by this low proportion of patients with severe symptoms requiring medical attention (and, subsequently, being tested for SARS-Cov-2). The Spanish pulmonary hypertension registry is currently collecting information about all PAH and CTEPH patients diagnosed with COVID-19, aiming to improve our knowledge of the prognostic implications of the disease in this population.

Figure 2. Reported cases and outcomes of the coronavirus disease of 2019 among pulmonary arterial hypertension and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension patients. PH: Pulmonary hypertension, PAH: Pulmonary arterial hypertension and CTEPH: Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension.

The chronic pathological findings in PAH and CTEPH somehow remind of those found in COVID-19 specimens. In fact, some experimental treatments tested for PAH such as recombinant ACE2, synthetic vasoactive intestinal peptide or IL-6 antagonists are already being tested in clinical trials for COVID-19 pneumonia, which support the hypothesis of pathophysiological similarities between both conditions [40]. This makes this population extremely vulnerable to acute conditions, especially to those causing severe respiratory failure [11]. In fact, infectious conditions are a common cause of decompensated right heart failure and death in these patients [39].

Although our observations of a benign course in PAH and CTEPH patients require caution, we described some pathophysiological characteristics that could explain this benign course [15][17].

4. Conclusions

Pulmonary damage associated to COVID-19 is a complex merge of different interrelated physiopathological processes in which endothelial dysfunction seems to play a pivotal role, leading to the development of thrombosis and vasomotor disturbances responsible for severe respiratory failure.

Although the scarcity of available data requires caution, the reported lethality of COVID-19 among PAH and CTEPH patients is low. The epidemiologic and prognostic impacts of COVID-19 in this population should be evaluated through international registries.

The role of chronic anticoagulation and specific PH therapies as protective measures against the described endothelial dysfunctions requires further investigation with placebo-controlled randomized trials, avoiding futile or even harmful interventions.

Last, due to severe endothelial dysfunctions, the higher incidences of thrombotic events and possible residual lung fibrosis, COVID-19 patients may require tight follow-ups to discard the possibility of PH as a chronic sequela of the disease.

1. Signs and Symptoms

| Symptom | Range |

|---|---|

| Fever | 83–99% |

| Cough | 59–82% |

| Loss of appetite | 40–84% |

| Fatigue | 44–70% |

| Shortness of breath | 31–40% |

| Coughing up sputum | 28–33% |

| Muscle aches and pains | 11–35% |

Fever is the most common symptom of COVID-19,[13] but is highly variable in severity and presentation, with some older, immunocompromised, or critically ill people not having fever at all.[39][40] In one study, only 44% of people had fever when they presented to the hospital, while 89% went on to develop fever at some point during their hospitalization.[41] Other common symptoms include cough, loss of appetite, fatigue, shortness of breath, sputum production, and muscle and joint pains.[13][1][5][42] Symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhoea have been observed in varying percentages.[43][44][45] Less common symptoms include sneezing, runny nose, sore throat, and skin lesions.[46] Some cases in China initially presented with only chest tightness and palpitations.[47] A decreased sense of smell or disturbances in taste may occur.[48][49] Loss of smell was a presenting symptom in 30% of confirmed cases in South Korea.[14][50] As is common with infections, there is a delay between the moment a person is first infected and the time he or she develops symptoms. This is called the incubation period. The typical incubation period for COVID‑19 is five or six days, but it can range from one to fourteen days[6][51] with approximately ten percent of cases taking longer.[52][53][54] An early key to the diagnosis is the tempo of the illness. Early symptoms may include a wide variety of symptoms but infrequently involves shortness of breath. Shortness of breath usually develops several days after initial symptoms. Shortness of breath that begins immediately along with fever and cough is more likely to be anxiety than COVID-19. The most critical days of illness tend to be those following the development of shortness of breath.[55] A minority of cases do not develop noticeable symptoms at any point in time.[56] These asymptomatic carriers tend not to get tested, and their role in transmission is not fully known.[57][58] Preliminary evidence suggested they may contribute to the spread of the disease.[59] In June 2020, a spokeswoman of WHO said that asymptomatic transmission appears to be "rare," but the evidence for the claim was not released.[60] The next day, WHO clarified that they had intended a narrow definition of "asymptomatic" that did not include pre-symptomatic or paucisymptomatic (weak symptoms) transmission and that up to 41% of transmission may be asymptomatic. Transmission without symptoms does occur.[56]

2. Cause

Transmission

<section begin="Transmission"/> alt=Cough/sneeze droplets visualised in dark background using Tyndall scattering|thumb|Respiratory droplets produced when a man sneezes, visualised using Tyndall scattering COVID‑19 is a new disease, and many of the details of its spread are still under investigation.[6][20][22] It spreads easily between people—easier than influenza but not as easily as measles.[20] People are most infectious when they show symptoms (even mild or non-specific symptoms), but may be infectious for up to two days before symptoms appear (pre-symptomatic transmission).[22] They remain infectious an estimated seven to twelve days in moderate cases and an average of two weeks in severe cases.[22] People can also transmit the virus without showing any symptom (asymptomatic transmission), but it is unclear how often this happens.[6][20][22] A June 2020 review found that 40–45% of infected people are asymptomatic.[61] COVID-19 spreads primarily when people are in close contact and one person inhales small droplets produced by an infected person (symptomatic or not) coughing, sneezing, talking, or singing.[22][62] The WHO recommends 1 metre (3 ft) of social distance;[6] the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends 2 metres (6 ft).[20] Transmission may also occur through aerosols, smaller droplets that are able to stay suspended in the air for longer periods of time.[24] Experimental results show the virus can survive in aerosol up to three hours.[63] Some outbreaks have also been reported in crowded and inadequately ventilated indoor locations where infected persons spend long periods of time (such as restaurants and nightclubs).[64] Aerosol transmission in such locations has not been ruled out.[24] Some medical procedures performed on COVID-19 patients in health facilities can generate those smaller droplets,[65] and result in the virus being transmitted more easily than normal.[6][22] When the contaminated droplets fall to floors or surfaces they can, though less commonly, remain infectious if people touch contaminated surfaces and then their eyes, nose or mouth with unwashed hands.[6] On surfaces the amount of viable active virus decreases over time until it can no longer cause infection,[22] and surfaces are thought not to be the main way the virus spreads.[20] It is unknown what amount of virus on surfaces is required to cause infection via this method, but it can be detected for up to four hours on copper, up to one day on cardboard, and up to three days on plastic (polypropylene) and stainless steel (AISI 304).[22][66][67] Surfaces are easily decontaminated with household disinfectants which destroy the virus outside the human body or on the hands.[6] Disinfectants or bleach are not a treatment for COVID‑19, and cause health problems when not used properly, such as when used inside the human body.[68] Sputum and saliva carry large amounts of virus.[6][20][22][69] Although COVID‑19 is not a sexually transmitted infection, direct contact such as kissing, intimate contact, and fecal–oral routes are suspected to transmit the virus.[70][71] The virus may occur in breast milk, but it's unknown whether it's infectious and transmittable to the baby.[72][73] Estimates of the number of people infected by one person with COVID-19, the R0, have varied. The WHO's initial estimates of R0 were 1.4–2.5 (average 1.95), however an early April 2020 review found the basic R0 (without control measures) to be higher at 3.28 and the median R0 to be 2.79.[74]<section end="Transmission" />

Virology

thumb|Illustration of SARSr-CoV virion Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus, first isolated from three people with pneumonia connected to the cluster of acute respiratory illness cases in Wuhan.[75] All features of the novel SARS-CoV-2 virus occur in related coronaviruses in nature.[76] Outside the human body, the virus is destroyed by household soap, which bursts its protective bubble.[26] SARS-CoV-2 is closely related to the original SARS-CoV.[77] It is thought to have an animal (zoonotic) origin. Genetic analysis has revealed that the coronavirus genetically clusters with the genus Betacoronavirus, in subgenus Sarbecovirus (lineage B) together with two bat-derived strains. It is 96% identical at the whole genome level to other bat coronavirus samples (BatCov RaTG13).[46] In February 2020, Chinese researchers found that there is only one amino acid difference in the binding domain of the S protein between the coronaviruses from pangolins and those from humans; however, whole-genome comparison to date found that at most 92% of genetic material was shared between pangolin coronavirus and SARS-CoV-2, which is insufficient to prove pangolins to be the intermediate host.[78]

3. Pathophysiology

The lungs are the organs most affected by COVID‑19 because the virus accesses host cells via the enzyme angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), which is most abundant in type II alveolar cells of the lungs.[79] The virus uses a special surface glycoprotein called a "spike" (peplomer) to connect to ACE2 and enter the host cell.[80] The density of ACE2 in each tissue correlates with the severity of the disease in that tissue and some have suggested decreasing ACE2 activity might be protective,[81][82] though another view is that increasing ACE2 using angiotensin II receptor blocker medications could be protective.[83] As the alveolar disease progresses, respiratory failure might develop and death may follow.[82] SARS-CoV-2 may also cause respiratory failure through affecting the brainstem as other coronaviruses have been found to invade the central nervous system (CNS). While virus has been detected in cerebrospinal fluid of autopsies, the exact mechanism by which it invades the CNS remains unclear and may first involve invasion of peripheral nerves given the low levels of ACE2 in the brain.[84][85] The virus also affects gastrointestinal organs as ACE2 is abundantly expressed in the glandular cells of gastric, duodenal and rectal epithelium[86] as well as endothelial cells and enterocytes of the small intestine.[87] The virus can cause acute myocardial injury and chronic damage to the cardiovascular system.[88] An acute cardiac injury was found in 12% of infected people admitted to the hospital in Wuhan, China,[44] and is more frequent in severe disease.[89] Rates of cardiovascular symptoms are high, owing to the systemic inflammatory response and immune system disorders during disease progression, but acute myocardial injuries may also be related to ACE2 receptors in the heart.[88] ACE2 receptors are highly expressed in the heart and are involved in heart function.[88][90] A high incidence of thrombosis (31%) and venous thromboembolism (25%) have been found in ICU patients with COVID‑19 infections, and may be related to poor prognosis.[91][92] Blood vessel dysfunction and clot formation (as suggested by high D-dimer levels) are thought to play a significant role in mortality, incidences of clots leading to pulmonary embolisms, and ischaemic events within the brain have been noted as complications leading to death in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2. Infection appears to set off a chain of vasoconstrictive responses within the body, constriction of blood vessels within the pulmonary circulation has also been posited as a mechanism in which oxygenation decreases alongside the presentation of viral pneumonia.[93] Another common cause of death is complications related to the kidneys.[93] Early reports show that up to 30% of hospitalized patients in both China and New York have experienced some injury to their kidneys, including some persons with no previous kidney problems.[94] Autopsies of people who died of COVID‑19 have found diffuse alveolar damage (DAD), and lymphocyte-containing inflammatory infiltrates within the lung.[95]

Immunopathology

Although SARS-CoV-2 has a tropism for ACE2-expressing epithelial cells of the respiratory tract, patients with severe COVID‑19 have symptoms of systemic hyperinflammation. Clinical laboratory findings of elevated IL-2, IL-7, IL-6, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), interferon-γ inducible protein 10 (IP-10), monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1), macrophage inflammatory protein 1-α (MIP-1α), and tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) indicative of cytokine release syndrome (CRS) suggest an underlying immunopathology.[44] Additionally, people with COVID‑19 and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) have classical serum biomarkers of CRS, including elevated C-reactive protein (CRP), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), D-dimer, and ferritin.[96] Systemic inflammation results in vasodilation, allowing inflammatory lymphocytic and monocytic infiltration of the lung and the heart. In particular, pathogenic GM-CSF-secreting T-cells were shown to correlate with the recruitment of inflammatory IL-6-secreting monocytes and severe lung pathology in COVID‑19 patients. Lymphocytic infiltrates have also been reported at autopsy.[95]

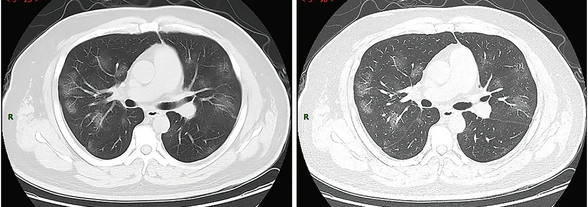

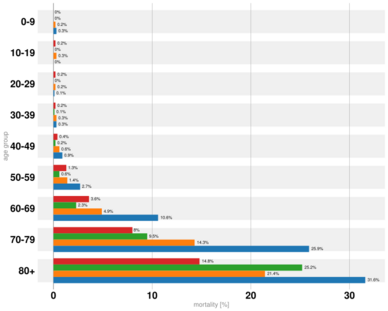

4. Diagnosis

thumb|US CDC rRT-PCR test kit for COVID-19[97] The WHO has published several testing protocols for the disease.[98] The standard method of testing is real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR).[99] The test is typically done on respiratory samples obtained by a nasopharyngeal swab; however, a nasal swab or sputum sample may also be used.[25][100] Results are generally available within a few hours to two days.[101][102] Blood tests can be used, but these require two blood samples taken two weeks apart, and the results have little immediate value.[103] Chinese scientists were able to isolate a strain of the coronavirus and publish the genetic sequence so laboratories across the world could independently develop polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests to detect infection by the virus.[10][104][105] (As of April 2020), antibody tests (which may detect active infections and whether a person had been infected in the past) were in development, but not yet widely used.[106][107][108] Antibody tests may be most accurate 2–3 weeks after a person's symptoms start.[109] The Chinese experience with testing has shown the accuracy is only 60 to 70%.[110] The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first point-of-care test on 21 March 2020 for use at the end of that month.[111] The absence or presence of COVID-19 signs and symptoms alone is not reliable enough for an accurate diagnosis.[112] Diagnostic guidelines released by Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University suggested methods for detecting infections based upon clinical features and epidemiological risk. These involved identifying people who had at least two of the following symptoms in addition to a history of travel to Wuhan or contact with other infected people: fever, imaging features of pneumonia, normal or reduced white blood cell count, or reduced lymphocyte count.[113] A study asked hospitalised COVID‑19 patients to cough into a sterile container, thus producing a saliva sample, and detected the virus in eleven of twelve patients using RT-PCR. This technique has the potential of being quicker than a swab and involving less risk to health care workers (collection at home or in the car).[69] Along with laboratory testing, chest CT scans may be helpful to diagnose COVID‑19 in individuals with a high clinical suspicion of infection but are not recommended for routine screening.[26][27] Bilateral multilobar ground-glass opacities with a peripheral, asymmetric, and posterior distribution are common in early infection.[26] Subpleural dominance, crazy paving (lobular septal thickening with variable alveolar filling), and consolidation may appear as the disease progresses.[26][114] In late 2019, the WHO assigned emergency ICD-10 disease codes U07.1 for deaths from lab-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection and U07.2 for deaths from clinically or epidemiologically diagnosed COVID‑19 without lab-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection.[115]

Pathology

Few data are available about microscopic lesions and the pathophysiology of COVID‑19.[116][117] The main pathological findings at autopsy are:

- Macroscopy: pleurisy, pericarditis, lung consolidation and pulmonary oedema

- Four types of severity of viral pneumonia can be observed:

- minor pneumonia: minor serous exudation, minor fibrin exudation

- mild pneumonia: pulmonary oedema, pneumocyte hyperplasia, large atypical pneumocytes, interstitial inflammation with lymphocytic infiltration and multinucleated giant cell formation

- severe pneumonia: diffuse alveolar damage (DAD) with diffuse alveolar exudates. DAD is the cause of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and severe hypoxemia.

- healing pneumonia: organisation of exudates in alveolar cavities and pulmonary interstitial fibrosis

- plasmocytosis in BAL[118]

- Blood: disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC);[119] leukoerythroblastic reaction[120]

- Liver: microvesicular steatosis

5. Prevention

thumb|upright=1.5|Progressively stronger mitigation efforts to reduce the number of active cases at any given time—"[[flattening the curve"—allows healthcare services to better manage the same volume of patients.[122][123][124] Likewise, progressively greater increases in healthcare capacity—called raising the line—such as by increasing bed count, personnel, and equipment, helps to meet increased demand.[125]]] thumb|upright=1.5|Mitigation attempts that are inadequate in strictness or duration—such as premature relaxation of distancing rules or stay-at-home orders—can allow a resurgence after the initial surge and mitigation.[123][126] A COVID-19 vaccine is not expected until 2021 at the earliest.[127] The US National Institutes of Health guidelines do not recommend any medication for prevention of COVID‑19, before or after exposure to the SARS-CoV-2 virus, outside the setting of a clinical trial.[128][129] Without a vaccine, other prophylactic measures, or effective treatments, a key part of managing COVID‑19 is trying to decrease and delay the epidemic peak, known as "flattening the curve".[123] This is done by slowing the infection rate to decrease the risk of health services being overwhelmed, allowing for better treatment of current cases, and delaying additional cases until effective treatments or a vaccine become available.[123][126] Preventive measures to reduce the chances of infection include staying at home, wearing a mask in public, avoiding crowded places, keeping distance from others, washing hands with soap and water often and for at least 20 seconds, practising good respiratory hygiene, and avoiding touching the eyes, nose, or mouth with unwashed hands.[130][131][132][133] The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO) recommend individuals wear non-medical face coverings in public settings where there is an increased risk of transmission and where social distancing measures are difficult to maintain.[134][30][135] This recommendation is meant to reduce the spread of the disease by asymptomatic and pre-symtomatic individuals and is complementary to established preventive measures such as social distancing.[30][136] Face coverings limit the volume and travel distance of expiratory droplets dispersed when talking, breathing, and coughing.[30][136] Many countries and local jurisdictions encourage or mandate the use of face masks or cloth face coverings by members of the public to limit the spread of the virus.[137][138][139][140] Masks are also strongly recommended for those who may have been infected and those taking care of someone who may have the disease.[141] When not wearing a mask, the CDC recommends covering the mouth and nose with a tissue when coughing or sneezing and recommends using the inside of the elbow if no tissue is available.[131] Proper hand hygiene after any cough or sneeze is encouraged.[131] Social distancing strategies aim to reduce contact of infected persons with large groups by closing schools and workplaces, restricting travel, and cancelling large public gatherings.[142] Distancing guidelines also include that people stay at least 6 feet (1.8 m) apart.[143] After the implementation of social distancing and stay-at-home orders, many regions have been able to sustain an effective transmission rate ("Rt") of less than one, meaning the disease is in remission in those areas.[144] The CDC also recommends that individuals wash hands often with soap and water for at least 20 seconds, especially after going to the toilet or when hands are visibly dirty, before eating and after blowing one's nose, coughing or sneezing. The CDC further recommends using an alcohol-based hand sanitiser with at least 60% alcohol, but only when soap and water are not readily available.[131] For areas where commercial hand sanitisers are not readily available, the WHO provides two formulations for local production. In these formulations, the antimicrobial activity arises from ethanol or isopropanol. Hydrogen peroxide is used to help eliminate bacterial spores in the alcohol; it is "not an active substance for hand antisepsis". Glycerol is added as a humectant.[145] Those diagnosed with COVID‑19 or who believe they may be infected are advised by the CDC to stay home except to get medical care, call ahead before visiting a healthcare provider, wear a face mask before entering the healthcare provider's office and when in any room or vehicle with another person, cover coughs and sneezes with a tissue, regularly wash hands with soap and water and avoid sharing personal household items.[32][146] Sanitizing of frequently touched surfaces is also recommended or required by regulation for businesses and public facilities; the United States Environmental Protection Agency maintains a list of products expected to be effective.[147] On 7 July 2020, the WHO said in a press conference that it will issue new guidelines about airborne transmission in settings with close contact and poor ventilation.[148] For health care professionals who may come into contact with COVID-19 positive bodily fluids, using personal protective coverings on exposed body parts improves protection from the virus.[149] Breathable personal protective equipment improves user-satisfaction and may offer a similar level of protection from the virus.[149] In addition, adding tabs and other modifications to the protective equipment may reduce the risk of contamination during donning and doffing (putting on and taking off the equipment).[149] Implementing an evidence-based donning and doffing protocol such as a one-step glove and gown removal technique, giving oral instructions while donning and doffing, double gloving, and the use of glove disinfection may also improve protection for health care professionals.[149]

6. Management

People are managed with supportive care, which may include fluid therapy, oxygen support, and supporting other affected vital organs.[150][151][152] The CDC recommends those who suspect they carry the virus wear a simple face mask.[32] Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) has been used to address the issue of respiratory failure, but its benefits are still under consideration.[153] Personal hygiene and a healthy lifestyle and diet have been recommended to improve immunity.[154] Supportive treatments may be useful in those with mild symptoms at the early stage of infection.[155] The WHO, the Chinese National Health Commission, and the United States' National Institutes of Health have published recommendations for taking care of people who are hospitalised with COVID‑19.[128][156][157] Intensivists and pulmonologists in the US have compiled treatment recommendations from various agencies into a free resource, the IBCC.[158][159]

7. Prognosis

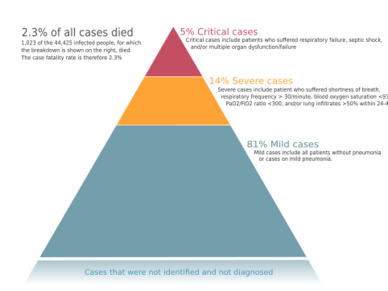

The severity of COVID‑19 varies. The disease may take a mild course with few or no symptoms, resembling other common upper respiratory diseases such as the common cold. Mild cases typically recover within two weeks, while those with severe or critical diseases may take three to six weeks to recover. Among those who have died, the time from symptom onset to death has ranged from two to eight weeks.[46] Children make up a small proportion of reported cases, with about 1% of cases being under 10 years and 4% aged 10–19 years.[22] They are likely to have milder symptoms and a lower chance of severe disease than adults. In those younger than 50 years the risk of death is less than 0.5%, while in those older than 70 it is more than 8%.[166][167][168] Pregnant women may be at higher risk of severe COVID‑19 infection based on data from other similar viruses, like severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), but data for COVID‑19 is lacking.[169][170] According to scientific reviews smokers are more likely to require intensive care or die compared to non-smokers,[171][172] air pollution is similarly associated with risk factors,[172] and obesity contributes to an increased health risk of COVID-19.[172][173][174] A European multinational study of hospitalized children published in The Lancet on June 25, 2020 found that about 8% of children admitted to a hospital needed intensive care. 4 out of 582 children (0.7%) died, although the actual mortality rate could be “substantially lower” since milder cases that did not seek medical help were not included in the study.[175]

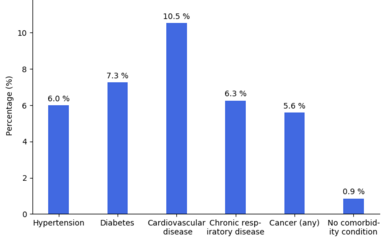

Comorbidities

Most of those who die of COVID‑19 have pre-existing (underlying) conditions, including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease.[176] The Istituto Superiore di Sanità reported that out of 8.8% of deaths where medical charts were available, 97% of people had at least one comorbidity with the average person having 2.7 diseases.[177] According to the same report, the median time between the onset of symptoms and death was ten days, with five being spent hospitalised. However, people transferred to an ICU had a median time of seven days between hospitalisation and death.[177] In a study of early cases, the median time from exhibiting initial symptoms to death was 14 days, with a full range of six to 41 days.[178] In a study by the National Health Commission (NHC) of China, men had a death rate of 2.8% while women had a death rate of 1.7%.[179] In 11.8% of the deaths reported by the National Health Commission of China, heart damage was noted by elevated levels of troponin or cardiac arrest.[47] According to March data from the United States, 89% of those hospitalised had preexisting conditions.[180] Most critical respiratory comorbidities according to the CDC, are: moderate or severe Asthma, pre-existing COPD, pulmonary fibrosis, cystic fibrosis.[181] Current evidence stemming from meta - analysis of several smaller research papers, also suggest that smoking can be assosiated with worse patient outcomes [182][183] When someone with existing respiratory problems is infected with COVID-19, they might be at greater risk for severe symptoms.[184] COVID-19 also poses a greater risk to people who misuse opioids and methamphetamines, insofar as their drug use may have caused lung damage.[185]

Complications and long-term effects

Complications may include pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), multi-organ failure, septic shock, and death.[10][16][186][187] Cardiovascular complications may include heart failure, arrhythmias, heart inflammation, and blood clots.[188] Approximately 20–30% of people who present with COVID‑19 have elevated liver enzymes reflecting liver injury.[189][129] Neurologic manifestations include seizure, stroke, encephalitis, and Guillain–Barré syndrome (which includes loss of motor functions).[190] Following the infection, children may develop paediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome, which has symptoms similar to Kawasaki disease, which can be fatal.[191][192] Concerns have been raised about long-term sequelae of the disease. The Hong Kong Hospital Authority found a drop of 20% to 30% in lung capacity in some people who recovered from the disease, and lung scans suggested organ damage.[193] This may also lead to post-intensive care syndrome following recovery.[194]

Immunity

It is unknown (as of April 2020) if past infection provides effective and long-term immunity in people who recover from the disease.[195][196] Some of the infected have been reported to develop protective antibodies, so acquired immunity is presumed likely, based on the behaviour of other coronaviruses.[197] Cases in which recovery from COVID‑19 was followed by positive tests for coronavirus at a later date have been reported.[198][199][200][201] However, these cases are believed to be lingering infection rather than reinfection,[201] or false positives due to remaining RNA fragments.[202] An investigation by the Korean CDC of 285 individuals who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 in PCR tests administered days or weeks after recovery from COVID-19 found no evidence that these individuals were contagious at this later time.[203] Some other coronaviruses circulating in people are capable of reinfection after roughly a year.[204][205]

8. History

The virus is thought to be natural and has an animal origin,[76] through spillover infection.[206] The first known human infections were in China. A study of the first 41 cases of confirmed COVID‑19, published in January 2020 in The Lancet, reported the earliest date of onset of symptoms as 1 December 2019.[207][208][209] Official publications from the WHO reported the earliest onset of symptoms as 8 December 2019.[210] Human-to-human transmission was confirmed by the WHO and Chinese authorities by 20 January 2020.[211][212] According to official Chinese sources, these were mostly linked to the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market, which also sold live animals.[213] In May 2020, George Gao, the director of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, said animal samples collected from the seafood market had tested negative for the virus, indicating that the market was the site of an early superspreading event, but it was not the site of the initial outbreak.[214] Traces of the virus have been found in wastewater that was collected from Milan and Turin, Italy, on 18 December 2019.[215] There are several theories about where the very first case (the so-called patient zero) originated.[216] According to an unpublicised report from the Chinese government, the first case can be traced back to 17 November 2019; the person was a 55-year old citizen in the Hubei province. There were four men and five women reported to be infected in November, but none of them were "patient zero".[12] By December 2019, the spread of infection was almost entirely driven by human-to-human transmission.[161][217] The number of coronavirus cases in Hubei gradually increased, reaching 60 by 20 December[218] and at least 266 by 31 December.[219] On 24 December, Wuhan Central Hospital sent a bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BAL) sample from an unresolved clinical case to sequencing company Vision Medicals. On 27 and 28 December, Vision Medicals informed the Wuhan Central Hospital and the Chinese CDC of the results of the test, showing a new coronavirus.[220] A pneumonia cluster of unknown cause was observed on 26 December and treated by the doctor Zhang Jixian in Hubei Provincial Hospital, who informed the Wuhan Jianghan CDC on 27 December.[221] On 30 December, a test report addressed to Wuhan Central Hospital, from company CapitalBio Medlab, stated an erroneous positive result for SARS, causing a group of doctors at Wuhan Central Hospital to alert their colleagues and relevant hospital authorities of the result. That evening, the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission issued a notice to various medical institutions on "the treatment of pneumonia of unknown cause".[222] Eight of these doctors, including Li Wenliang (punished on 3 January),[223] were later admonished by the police for spreading false rumours, and another, Ai Fen, was reprimanded by her superiors for raising the alarm.[224] The Wuhan Municipal Health Commission made the first public announcement of a pneumonia outbreak of unknown cause on 31 December, confirming 27 cases[225][226][227]—enough to trigger an investigation.[228] During the early stages of the outbreak, the number of cases doubled approximately every seven and a half days.[229] In early and mid-January 2020, the virus spread to other Chinese provinces, helped by the Chinese New Year migration and Wuhan being a transport hub and major rail interchange.[230] On 20 January, China reported nearly 140 new cases in one day, including two people in Beijing and one in Shenzhen.[231] Later official data shows 6,174 people had already developed symptoms by then,[232] and more may have been infected.[233] A report in The Lancet on 24 January indicated human transmission, strongly recommended personal protective equipment for health workers, and said testing for the virus was essential due to its "pandemic potential".[234][235] On 30 January, the WHO declared the coronavirus a public health emergency of international concern.[233] By this time, the outbreak spread by a factor of 100 to 200 times.[236] On 31 January 2020, Italy had its first confirmed cases, two tourists from China.[237] As of 13 March 2020, the WHO considered Europe the active centre of the pandemic.[238] On 19 March 2020, Italy overtook China as the country with the most deaths.[239] By 26 March, the United States had overtaken China and Italy with the highest number of confirmed cases in the world.[240] Research on coronavirus genomes indicates the majority of COVID-19 cases in New York came from European travellers, rather than directly from China or any other Asian country.[241] Retesting of prior samples found a person in France who had the virus on 27 December 2019[242][243] and a person in the United States who died from the disease on 6 February 2020.[244] On 11 June 2020, after 55 days without a locally transmitted case,[245] Beijing reported the first COVID-19 case, followed by two more cases on 12 June.[246] By 15 June, 79 cases were officially confirmed.[247] Most of these patients went to Xinfadi Wholesale Market.[245][248]

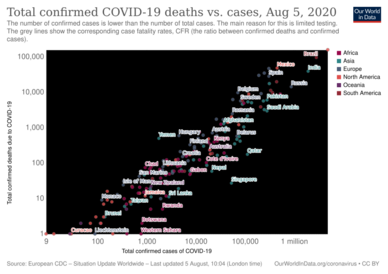

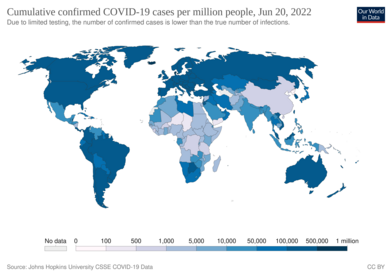

9. Epidemiology

Several measures are commonly used to quantify mortality.[249] These numbers vary by region and over time and are influenced by the volume of testing, healthcare system quality, treatment options, time since the initial outbreak, and population characteristics such as age, sex, and overall health.[250] The death-to-case ratio reflects the number of deaths divided by the number of diagnosed cases within a given time interval. Based on Johns Hopkins University statistics, the global death-to-case ratio is 1.90% (5,425,817/285,043,163) as of 30 December 2021.[8] The number varies by region.[251] Other measures include the case fatality rate (CFR), which reflects the percent of diagnosed individuals who die from a disease, and the infection fatality rate (IFR), which reflects the percent of infected individuals (diagnosed and undiagnosed) who die from a disease. These statistics are not time-bound and follow a specific population from infection through case resolution. Many academics have attempted to calculate these numbers for specific populations.[252] Outbreaks have occurred in prisons due to crowding and an inability to enforce adequate social distancing.[253][254] In the United States, the prisoner population is aging and many of them are at high risk for poor outcomes from COVID‑19 due to high rates of coexisting heart and lung disease, and poor access to high-quality healthcare.[253]

Infection fatality rate

Infection fatality rate (or infection fatality ratio) is distinguished from case fatality rate. The case fatality rate ("CFR") for a disease is the proportion of deaths from the disease compared to the total number of people diagnosed with the disease (within a certain period of time). The infection fatality ratio ("IFR"), in contrast, is the proportion of deaths among all the infected individuals. IFR, unlike CFR, attempts to account for all asymptomatic and undiagnosed infections. Our World in Data states that, as of 25 March 2020, the infection fatality rate (IFR) for coronavirus cannot be accurately calculated.[257] In February, the World Health Organization reported estimates of IFR between 0.33% and 1%.[258][259] On 2 July, The WHO's Chief Scientist reported that the average IFR estimate presented at a two-day WHO expert forum was about 0.6%.[260][261] The CDC estimates for planning purposes that the infection fatality rate is 0.65% and that 40% of infected individuals are asymptomatic, suggesting a fatality rate among those who are symptomatic of 1.08% (.65/60) (as of 10 July).[262][263] According to the University of Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM), random antibody testing in Germany suggested a national IFR of 0.37% (0.12% to 0.87%).[264][265][266] To get a better view on the number of people infected, (As of April 2020), initial antibody testing had been carried out, but peer-reviewed scientific analyses had not yet been published.[267][268] On 1 May antibody testing in New York City suggested an IFR of 0.86%.[269] Firm lower limits of infection fatality rates have been established in a number of locations such as New York City and Bergamo in Italy since the IFR cannot be less than the population fatality rate. As of 10 July, in New York City , with a population of 8.4 million, 23,377 individuals (18,758 confirmed and 4,619 probable) have died with COVID-19 (0.28% of the population).[270] In Bergamo province, 0.57% of the population has died.[271]

Sex differences

Early reviews of epidemiologic data showed greater impact of the pandemic and a higher mortality rate in men in China and Italy.[272][1][273] The Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention reported the death rate was 2.8 percent for men and 1.7 percent for women.[274] Later reviews in June 2020 indicated that there is no significant difference in susceptibility or in CFR between genders.[275][276] One review acknowledges the different mortality rates in Chinese men, suggesting that it may be attributable to lifestyle choices such as smoking and drinking alcohol rather than genetic factors.[277] Sex-based immunological differences, lesser prevalence of smoking in women and men developing co-morbid conditions such as hypertension at a younger age than women could have contributed to the higher mortality in men.[278] In Europe, 57% of the infected people were men and 72% of those died with COVID-19 were men.[279] As of April 2020, the US government is not tracking sex-related data of COVID-19 infections.[280] Research has shown that viral illnesses like Ebola, HIV, influenza and SARS affect men and women differently.[280]

| Percent of infected people who are hospitalized | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–19 | 20–29 | 30–39 | 40–49 | 50–59 | 60–69 | 70–79 | 80+ | Total | |

| Female | Template:Shade (0.1–0.3) | Template:Shade (0.3–0.9) | Template:Shade (0.7–1.8) | Template:Shade (0.9–2.4) | Template:Shade (1.9–4.9) | Template:Shade (3.7–9.6) | Template:Shade (5.7–14.8) | Template:Shade (14.0–36.4) | Template:Shade (1.9–5.0) |

| Male | Template:Shade (0.1–0.3) | Template:Shade (0.4–1.1) | Template:Shade (0.9–2.2) | Template:Shade (1.1–3.0) | Template:Shade (2.3–6.1) | Template:Shade (4.8–12.6) | Template:Shade (8.0–20.7) | Template:Shade (27.3–70.9) | Template:Shade (2.4–6.2) |

| Total | Template:Shade (0.1–0.3) | Template:Shade (0.4–1.0) | Template:Shade (0.8–2.0) | Template:Shade (1.0–2.7) | Template:Shade (2.1–5.4) | Template:Shade (4.2–11.0) | Template:Shade (6.7–17.5) | Template:Shade (19.0–49.4) | Template:Shade (2.1–5.6) |

| Percent of hospitalized people who go to Intensive Care Unit | |||||||||

| 0–19 | 20–29 | 30–39 | 40–49 | 50–59 | 60–69 | 70–79 | 80+ | Total | |

| Female | Template:Shade (14.4–19.2) | Template:Shade (7.5–9.9) | Template:Shade (10.9–13.0) | Template:Shade (15.6–17.7) | Template:Shade (19.8–21.7) | Template:Shade (22.2–24.0) | Template:Shade (18.0–19.5) | Template:Shade (4.0–4.5) | Template:Shade (13.9–14.7) |

| Male | Template:Shade (23.2–31.0) | Template:Shade (12.2–15.9) | Template:Shade (17.6–20.9) | Template:Shade (25.3–28.5) | Template:Shade (32.0–34.8) | Template:Shade (36.0–38.6) | Template:Shade (29.2–31.3) | Template:Shade (6.5–7.2) | Template:Shade (22.6–23.6) |

| Total | Template:Shade (19.2–25.5) | Template:Shade (10.1–13.2) | Template:Shade (14.6–17.3) | Template:Shade (21.0–23.5) | Template:Shade (26.5–28.7) | Template:Shade (29.8–31.8) | Template:Shade (24.1–25.8) | Template:Shade (5.3–5.9) | Template:Shade (18.7–19.44) |

| Percent of hospitalized people who die | |||||||||

| 0–19 | 20–29 | 30–39 | 40–49 | 50–59 | 60–69 | 70–79 | 80+ | Total | |

| Female | Template:Shade (0.2–1.1) | Template:Shade (0.5–1.3) | Template:Shade (1.2–1.9) | Template:Shade (2.3–3.0) | Template:Shade (4.8–5.6) | Template:Shade (9.5–10.6) | Template:Shade (16.0–17.4) | Template:Shade (24.4–26.0) | Template:Shade (14.0–14.9) |

| Male | Template:Shade (0.3–1.5) | Template:Shade (0.8–1.9) | Template:Shade (1.7–2.7) | Template:Shade (3.4–4.4) | Template:Shade (7.0–8.2) | Template:Shade (14.1–15.6) | Template:Shade (23.7–25.6) | Template:Shade (36.1–38.2) | Template:Shade (20.8–21.7) |

| Total | Template:Shade (0.3–1.3) | Template:Shade (0.7–1.6) | Template:Shade (1.5–2.3) | Template:Shade (2.9–3.7) | Template:Shade (6.0–7.0) | Template:Shade (12.0–13.2) | Template:Shade (20.3–21.8) | Template:Shade (30.9–32.4) | Template:Shade (17.8–18.4) |

| Percent of infected people who die – infection fatality rate (IFR) | |||||||||

| 0–19 | 20–29 | 30–39 | 40–49 | 50–59 | 60–69 | 70–79 | 80+ | Total | |

| Female | Template:Shade (<0.001–0.002) | Template:Shade (0.002–0.009) | Template:Shade (0.01–0.03) | Template:Shade (0.02–0.07) | Template:Shade (0.1–0.3) | Template:Shade (0.4–1.0) | Template:Shade (1.0–2.5) | Template:Shade (3.5–9.2) | Template:Shade (0.3–0.7) |

| Male | Template:Shade (<0.001–0.003) | Template:Shade (0.004–0.02) | Template:Shade (0.02–0.05) | Template:Shade (0.04–0.1) | Template:Shade (0.2–0.5) | Template:Shade (0.7–1.9) | Template:Shade (2.0–5.1) | Template:Shade (10.1–26.3) | Template:Shade (0.5–1.3) |

| Total | Template:Shade (<0.001–0.002) | Template:Shade (0.003–0.01) | Template:Shade (0.01–0.04) | Template:Shade (0.03–0.09) | Template:Shade (0.1–0.36) | Template:Shade (0.5–1.4) | Template:Shade (1.4–3.7) | Template:Shade (6.0–15.6) | Template:Shade (0.4–1.0) |

| Numbers in parentheses are 95% credible intervals for the estimates. | |||||||||

Ethnic differences

In the US, a greater proportion of deaths due to COVID-19 have occurred among African Americans.[282] Structural factors that prevent African Americans from practicing social distancing include their concentration in crowded substandard housing and in "essential" occupations such as public transit and health care. Greater prevalence of lacking health insurance and care and of underlying conditions such as diabetes, hypertension and heart disease also increase their risk of death.[283] Similar issues affect Native American and Latino communities.[282] According to a US health policy non-profit, 34% of American Indian and Alaska Native People (AIAN) non-elderly adults are at risk of serious illness compared to 21% of white non-elderly adults.[284] The source attributes it to disproportionately high rates of many health conditions that may put them at higher risk as well as living conditions like lack of access to clean water.[285] Leaders have called for efforts to research and address the disparities.[286] In the U.K., a greater proportion of deaths due to COVID-19 have occurred in those of a Black, Asian, and other ethnic minority background.[287][288][289] Several factors such as poverty, poor nutrition and living in overcrowded properties, may have caused this.

10. Society and Culture

Name

During the initial outbreak in Wuhan, China, the virus and disease were commonly referred to as "coronavirus" and "Wuhan coronavirus",[290][291][292] with the disease sometimes called "Wuhan pneumonia".[293][294] In the past, many diseases have been named after geographical locations, such as the Spanish flu,[295] Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, and Zika virus.[296]

In January 2020, the World Health Organisation recommended 2019-nCov[297] and 2019-nCoV acute respiratory disease[298] as interim names for the virus and disease per 2015 guidance and international guidelines against using geographical locations (e.g. Wuhan, China), animal species or groups of people in disease and virus names to prevent social stigma.[299][300][301] The official names COVID‑19 and SARS-CoV-2 were issued by the WHO on 11 February 2020.[302] WHO chief Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus explained: CO for corona, VI for virus, D for disease and 19 for when the outbreak was first identified (31 December 2019).[303] The WHO additionally uses "the COVID‑19 virus" and "the virus responsible for COVID‑19" in public communications.[302]

Misinformation

After the initial outbreak of COVID‑19, misinformation and disinformation regarding the origin, scale, prevention, treatment, and other aspects of the disease rapidly spread online.[304][305][306]

Other health issues

The pandemic has had many impacts on global health beyond those caused by the COVID-19 disease itself. It has led to a reduction in hospital visits for other reasons. There have been 38% fewer hospital visits for heart attack symptoms in the United States and 40% fewer in Spain.[307] The head of cardiology at the University of Arizona said, "My worry is some of these people are dying at home because they're too scared to go to the hospital."[308] There is also concern that people with strokes and appendicitis are not seeking timely treatment.[308] Shortages of medical supplies have impacted people with various conditions.[309] In several countries there has been a marked reduction of spread of sexually transmitted infections, including HIV, attributable to COVID-19 quarantines and social distancing measures.[310][311] Similarly, in some places, rates of transmission of influenza and other respiratory viruses significantly decreased during the pandemic.[312][313][314] The pandemic has also negatively impacted mental health globally, including increased loneliness resulting from social distancing.[315]

11. Other Animals

Humans appear to be capable of spreading the virus to some other animals. A domestic cat in Liège, Belgium, tested positive after it started showing symptoms (diarrhoea, vomiting, shortness of breath) a week later than its owner, who was also positive.[316] Tigers and lions at the Bronx Zoo in New York, United States, tested positive for the virus and showed symptoms of COVID‑19, including a dry cough and loss of appetite.[317] Minks at two farms in the Netherlands also tested positive for COVID-19.[318] A study on domesticated animals inoculated with the virus found that cats and ferrets appear to be "highly susceptible" to the disease, while dogs appear to be less susceptible, with lower levels of viral replication. The study failed to find evidence of viral replication in pigs, ducks, and chickens.[319] In March 2020, researchers from the University of Hong Kong have shown that Syrian hamsters could be a model organism for COVID-19 research.[320]

12. Research

No medication or vaccine is approved with the specific indication to treat the disease.[321] International research on vaccines and medicines in COVID‑19 is underway by government organisations, academic groups, and industry researchers.[322][323] In March, the World Health Organisation initiated the "Solidarity Trial" to assess the treatment effects of four existing antiviral compounds with the most promise of efficacy.[324] The World Health Organization suspended hydroxychloroquine from its global drug trials for COVID-19 treatments on 26 May 2020 due to safety concerns. It had previously enrolled 3,500 patients from 17 countries in the Solidarity Trial.[325] France, Italy and Belgium also banned the use of hydroxychloroquine as a COVID-19 treatment.[326] There has been a great deal of COVID-19 research, involving accelerated research processes and publishing shortcuts to meet the global demand. To minimise the harm from misinformation, medical professionals and the public are advised to expect rapid changes to available information, and to be attentive to retractions and other updates.[327]

Vaccine

There is no available vaccine, but various agencies are actively developing vaccine candidates. Previous work on SARS-CoV is being used because both SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 use the ACE2 receptor to enter human cells.[328] Six vaccination strategies are being investigated. Four of these, as of early July 2020, are being tested in clinical trials.[329] First, researchers aim to build a whole virus vaccine. The use of such inactive virus aims to elicit a prompt immune response of the human body to a new infection with COVID‑19. A second strategy, subunit vaccines, aims to create a vaccine that sensitises the immune system to certain subunits of the virus. In the case of SARS-CoV-2, such research focuses on the S-spike protein that helps the virus intrude the ACE2 enzyme receptor. A third strategy is that of the nucleic acid vaccines (DNA or RNA vaccines, a novel technique for creating a vaccination). Fourthly, scientists are attempting to use viral vectors to deliver the SARS-CoV-2 antigen gene into the cell.[330] These can be replicating or non-replicating. As of early July 2020, only non-replicating viral vectors are in clinical trials. Viral vectors in clinical trials include Chimpanzee Adenovirus 63,[330] Adenovirus type-5,[329] and Adenovirus type-26.[331] Scientists are also working to develop an attenuated COVID-19 vaccine and a COVID-19 vaccine using virus-like particles, but these are still in preclinical research.[329] Experimental vaccines from any of these strategies would have to be tested for safety and efficacy.[332] Antibody-dependent enhancement has been suggested as a potential challenge for vaccine development for SARS-COV-2, but this is controversial.[333]

Medications

At least 29 phase II–IV efficacy trials in COVID‑19 were concluded in March 2020, or scheduled to provide results in April from hospitals in China.[334][335] There are more than 300 active clinical trials underway as of April 2020.[129] Seven trials were evaluating already approved treatments, including four studies on hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine.[335] Repurposed antiviral drugs make up most of the research, with nine phase III trials on remdesivir across several countries due to report by the end of April.[334][335] Other candidates in trials include vasodilators, corticosteroids, immune therapies, lipoic acid, bevacizumab, and recombinant angiotensin-converting enzyme 2.[335] The COVID‑19 Clinical Research Coalition has goals to 1) facilitate rapid reviews of clinical trial proposals by ethics committees and national regulatory agencies, 2) fast-track approvals for the candidate therapeutic compounds, 3) ensure standardised and rapid analysis of emerging efficacy and safety data and 4) facilitate sharing of clinical trial outcomes before publication.[336][337] Several existing medications are being evaluated for the treatment of COVID‑19,[321] including remdesivir, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, lopinavir/ritonavir, and lopinavir/ritonavir combined with interferon beta.[324][338] There is tentative evidence for efficacy by remdesivir, and on 1 May 2020, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) gave the drug an emergency use authorization for people hospitalized with severe COVID‑19.[339] Phase III clinical trials for several drugs are underway in several countries, including the US, China, and Italy.[321][334][340] There are mixed results as of 3 April 2020 as to the effectiveness of hydroxychloroquine as a treatment for COVID‑19, with some studies showing little or no improvement.[341][342] One study has shown an association between hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine use with higher death rates along with other side effects.[343][344] A retraction of this study by its authors was published by The Lancet on 4 June 2020.[345] The studies of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine with or without azithromycin have major limitations that have prevented the medical community from embracing these therapies without further study.[129] On 15 June 2020, the FDA updated the fact sheets for the emergency use authorization of remdesivir to warn that using chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine with remdesivir may reduce the antiviral activity of remdesivir.[346] In June, initial results from a randomised trial in the United Kingdom showed that dexamethasone reduced mortality by one third for patients who are critically ill on ventilators and one fifth for those receiving supplemental oxygen.[347] Because this is a well tested and widely available treatment this was welcomed by the WHO that is in the process of updating treatment guidelines to include dexamethasone or other steroids.[348][349] Based on those preliminary results, dexamethasone treatment has been recommended by the National Institutes of Health for patients with COVID-19 who are mechanically ventilated or who require supplemental oxygen but not in patients with COVID-19 who do not require supplemental oxygen.[350]

Cytokine storm

A cytokine storm can be a complication in the later stages of severe COVID‑19. There is preliminary evidence that hydroxychloroquine may be useful in controlling cytokine storms in late-phase severe forms of the disease.[351] Tocilizumab has been included in treatment guidelines by China's National Health Commission after a small study was completed.[352][353] It is undergoing a phase 2 non-randomised trial at the national level in Italy after showing positive results in people with severe disease.[354][355] Combined with a serum ferritin blood test to identify a cytokine storm (also called cytokine storm syndrome, not to be confused with cytokine release syndrome), it is meant to counter such developments, which are thought to be the cause of death in some affected people.[356][357][358] The interleukin-6 receptor antagonist was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to undergo a phase III clinical trial assessing its effectiveness on COVID‑19 based on retrospective case studies for the treatment of steroid-refractory cytokine release syndrome induced by a different cause, CAR T cell therapy, in 2017.[359] To date, there is no randomised, controlled evidence that tocilizumab is an efficacious treatment for CRS. Prophylactic tocilizumab has been shown to increase serum IL-6 levels by saturating the IL-6R, driving IL-6 across the blood-brain barrier, and exacerbating neurotoxicity while having no effect on the incidence of CRS.[360] Lenzilumab, an anti-GM-CSF monoclonal antibody, is protective in murine models for CAR T cell-induced CRS and neurotoxicity and is a viable therapeutic option due to the observed increase of pathogenic GM-CSF secreting T-cells in hospitalised patients with COVID‑19.[361] The Feinstein Institute of Northwell Health announced in March a study on "a human antibody that may prevent the activity" of IL-6.[362]

Passive antibodies

Transferring purified and concentrated antibodies produced by the immune systems of those who have recovered from COVID‑19 to people who need them is being investigated as a non-vaccine method of passive immunisation.[363][364] The safety and effectiveness of convalescent plasma as a treatment option requires further research.[364] This strategy was tried for SARS with inconclusive results.[363] Viral neutralisation is the anticipated mechanism of action by which passive antibody therapy can mediate defence against SARS-CoV-2. The spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 is the primary target for neutralizing antibodies.[365] It has been proposed that selection of broad-neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV might be useful for treating not only COVID-19 but also future SARS-related CoV infections.[365] Other mechanisms, however, such as antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity and/or phagocytosis, may be possible.[363] Other forms of passive antibody therapy, for example, using manufactured monoclonal antibodies, are in development.[363] Production of convalescent serum, which consists of the liquid portion of the blood from recovered patients and contains antibodies specific to this virus, could be increased for quicker deployment.[366]