The pivotal role of childhood nutrition has always roused a growing interest from the scientific community. Plant extracts play a significant role in the maintenance of human health and wellness, with the potential to modulate risk factors and manage symptoms for a large number of common childhood disorders such as memory impairment, respiratory illnesses, gastrointestinal disorders, metabolic derangements, and pathologies related to the oral cavity.

- childhood disorders

- plant extracts

- childhood supplementation

1. Introduction

The use of dietary supplements worldwide has increased in the last 30 years [1]. Dietary supplements are used in the age group ranging from birth to 18 years of age, by 31% of the population, to improve overall health (41%), maintain health (37%), supplement the diet (23%), prevent health problems (20%), and “boost immunity” (14%) [2]. From data by the World Health Organization (WHO), around 80% of the adult population in developing countries uses plant extracts for their health needs [3][4][5]. Plant extracts are also used for children, although their use must be regulated by the awareness that children differ from adults in terms of physical size, body composition, and physiology. Medicinal plants can be used to treat winter problems in a preventive context, and thus to strengthen the immune system and improve the body’s adaptation to seasonal disturbances, but they can also be used as a treatment for various symptomatic connotations. It is necessary to know how to regulate the use of such supplements according to a child’s body weight to avoid reaching toxic doses [6]. In a German study, 85% of children used one or more herbal supplement products [5]. Another study reported that 16% of Japanese pediatric surgical patients use herbal supplement products [7].

About 9% of newborns, from the first month of life, have been treated with herbal supplements, in particular, for mild neonatal ailments such as flatulence, teething, or colds. The extracts used are based on chamomile, mint, echinacea, fennel, catnip, and anise [8]. The belief that natural herbal products are safe, culturally significant, cheaper than some medical treatment options, and easily accessible, are some of the reasons why these products are being used [9].

Given that the correct use of food supplements is safe, it is important to rely on a trusted pediatrician in order to verify the existence of a real need to take supplements and subsequently to assess the correct dosage and identify the presence of any contraindications (some plant extracts/supplements cannot be used in children) both in situations of simple nutritional support and in conjunction with the intake of drugs for intercurrent or chronic pathological conditions.

2. Food Supplements and Childhood Illnesses

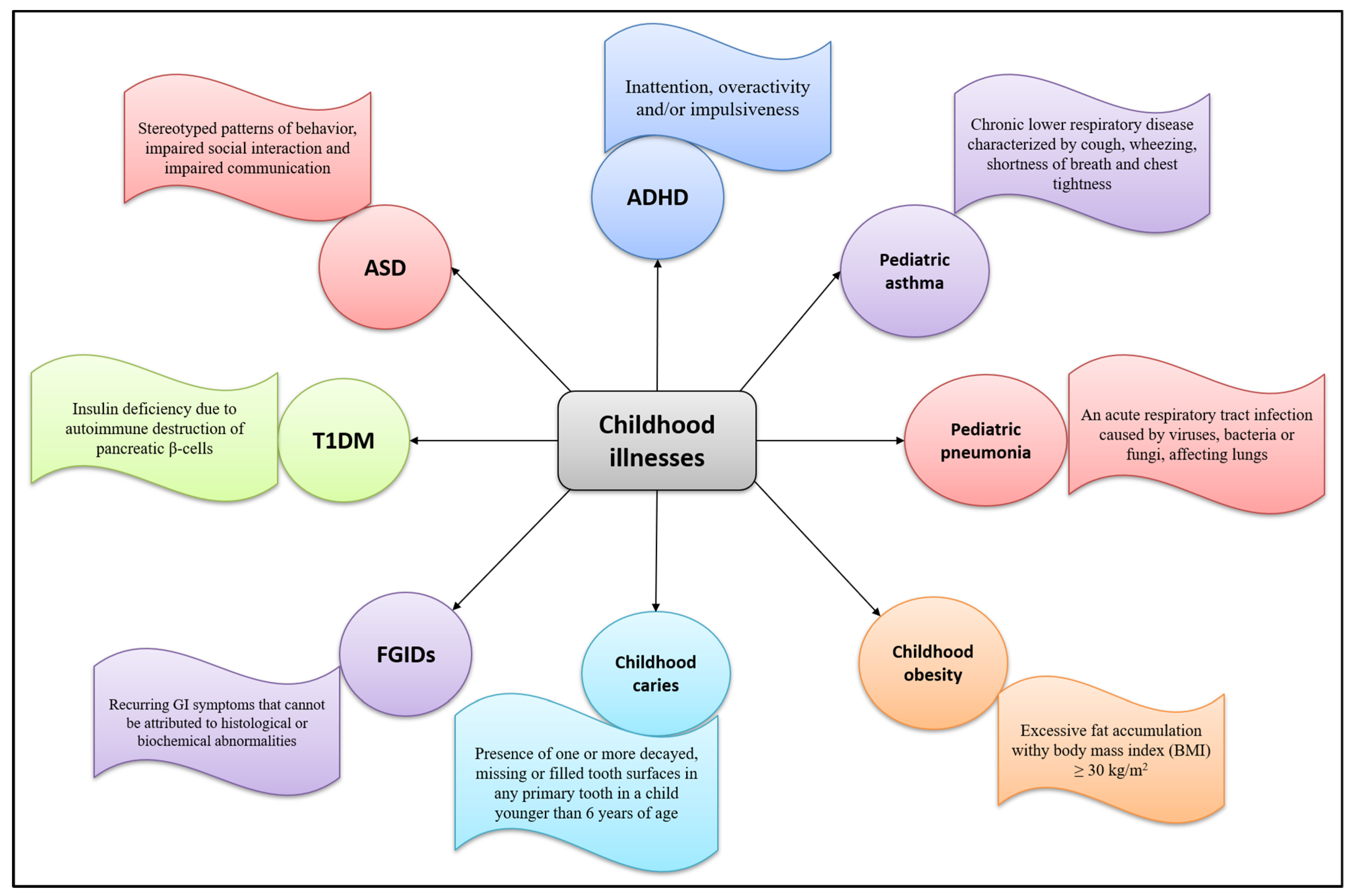

A food supplement is a product intended to supplement the diet in particular conditions of deficiency. Children with correct and balanced eating styles rarely need supplements, except for particular cases in the first year of life or in the presence of certain disorders or diseases. During childhood, plant extracts are used to treat symptoms of upper respiratory tract infections, sleeping problems, gastrointestinal disorders, or occasional and common ailments such as cough, cold, and sore throat. Figure 1 2 summarizes common childhood pathologies and their defining features.

2.1. Botanical Extracts

| Botanical Extract | Study Design | Intervention | Main Results | Reference | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound herbal preparation ( | M. officinalis, | | W. somnifera | , | B. monnieri | , | A. platensis | , and | C. asiatica | ) | Randomized controlled trial, 120 children with ADHD (mean age: 9.82 years for treatment group and 9.36 years for control group) were recruited. |

Three mL of compound herbal preparation 3 times a day in 50–60 mL water. | Significant improvement of TOVA scores, attention, cognition, and impulse control in intervention group. | [10] | ||||||

| M. officinalis | and | P. decandra | Crossover randomized triple-blinded controlled trial, 52 children with sleep bruxism with mean age of 6.62 years were selected. |

The study included 4 phases of 30-day treatment (placebo, | M. officinalis | 12 c, | P. decandra | 12c and | M. officinalis | 12c + | P. decandra | 12c) with a washout period of 15 days between treatments. | Significant decrease in VAS in | M. officinalis | treated phase. No improvement of results was seen in combination of | M. officinalis | with | P. decandra | . | [11] |

| F. vulgare | Double blind, placebo-controlled study, 125 infants with 2–12 weeks of age, diagnosed with infantile colic were selected for the trial. |

A mixture of 0.1% of | F. vulgare | oil emulsion and 0.4% polysorbate in water. Five to twenty milliliters of mixture administered 4 times a day before meal at a maximum dose of 12 mL/kg/day. |

Significant recovery of the colic symptoms in | F. vulgare | treated group. | [12] | ||||||||||||

| M. chamomilla | and | M. officinalis | Multicenter, randomized controlled trial, Children with infantile colic were recruited. |

Patients were treated with mixture of | M. chamomilla | , | M. officinalis | and tyndallized | Lactobacillus acidophilus | HA122 or | Lactobacillus reuteri | DSM 17,938 for 28 days. | One hundred and seventy-six children completed the study. The symptoms of infantile colic relieved with a significant decrease in mean daily crying in both groups. |

[13] | ||||||

| Herbal mixture of | M. chamomilla | , | A. officinalis | , | H. officinalis | , | M. sylvestris | , | A. capillus-veneris | , | Z. jujube | , and | G. glabra | Double-blind randomized clinical trial, 46 children aged 7–12 years old diagnosed with intermittent asthma were selected. |

Children were treated with herbal mixture (5 mL three times a day) or placebo for 5 days. | Significant reduction in the severity of cough and nighttime awakenings in the treatment group. No improvement of wheezing, respiratory distress, tachypnea, peak expiratory flow rate, asthma exacerbations, outpatient visits, oral administration of prednisone or β-agonists and hospitalization. |

[14] | |||

| Boswellic acid ( | B. serrata | ) | Nineteen children and adolescents (mean age of 8.4 years) with progressive or relapsed brain tumors were selected for trial. | Patients received boswellic acid at a maximum dose of 126 mg/kg/day for duration of 1–26 months (median 9 months). | Improvement of general status of patients and neurological symptoms (parses and ataxia), increased muscular strength, regression of peritumoral edema and regression of the volume of a tumor cyst. | [15] | ||||||||||||||

| V. officinalis | and | M. officinalis | Multicenter observational study, 918 children with restlessness and dyssomnia were recruited for the study. |

Each patient received a maximum of 2 × 2 tablets per day for 4 weeks, where each tablet contains valerian root dry extract (160 mg) and lemon balm extract (80 mg). | Improvement of symptoms associated with restlessness and dyssomnia in intervention group. | [16] | ||||||||||||||

| V. officinalis | Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial, 30 children with ADHD (age: 5–11 years) were selected. |

Patients were treated with | V. officinalis | mother tincture (MT) or | V. officinalis | 3X three times a day for 2 weeks. | A significant improvement in ADHD symptoms in patients treated with | V. officinalis | MT or 3X in reference to sustained attention, impulsivity, hyperactivity and anxiety. | [17] | ||||||||||

| Pediatric syrup Grintuss | ® | ( | G. robusta | , | H. italicum | , | P. lanceolata | , and honey) | Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial, 102 children aged 3–6 years, with persistent cough for at least 7 days up to 3 weeks and not treated with any antitussive agent were recruited. |

Patients were treated with placebo ( | n | = 51) or Grintuss | ® | syrup ( | n | = 51) 4 doses/day, 5 mL each dose for 8 days. | Significant improvement in daytime and night-time cough scores. | [18] | ||

| Polysaccharide-resin-honey (PRH)-based cough syrup ( | G. robusta | , | H. italicum | and | P. lanceolata | ) | Randomized, single-blind multicenter study, 150 children aged 2–5 years with upper respiratory tract infection, nocturnal and daytime cough and illness duration of ≤ 7 days were participated. |

Patients were treated with PRH cough syrup (20 mL/day) or carbocysteine based syrup (control, 25 mg/kg/day) in three divided doses for 3 consecutive days. | PRH cough syrup showed more rapid and greater improvement in all clinical cough symptoms measured compared to carbocysteine based syrup. | [19] | ||||||||||

| KalobaTUSS | ® | pediatric cough syrup (Acacia honey, | I. helenium | , | M. sylvestris | , | H. stoechas | , and | P. major | ) | Randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 106 children with persistent cough are recruited in the study. |

Patients were treated with cough syrup or placebo 4 doses daily, 5 mL each for 8 days. | Cough syrup significantly reduces the severity and duration of cough as compared to placebo. | [20] | ||||||

| Herbal triplet ( | V. officinalis | , | H. perforatum | and | P. incarnata | ) | Multicenter, prospective, observational study, 115 children aged 6–12 years with history of nervousness and agitation (including agitated depression) due to affective disorders were selected for the study. |

Dry extract of herbal triplet administered in tablet form via oral route, containing | V. officinalis | (28 mg/tablet), | H. perforatum | (60 mg/tablet) and | P. incarnate | (32 mg/tablet). Patients were accessed at baseline, after 2 weeks of treatment and then after 4 weeks of treatment. |

Herbal triplet showed a distinct improvement in children with attention problems, social withdrawal, and mood troubles (anxiety and depression). | [21] | ||||

| P. incarnata | Double-blind randomized clinical trial, 34 children with ADHD were recruited in an 8-week clinical trial. |

Children were treated with | P. incarnata | (0.04 mg/kg/day) or methylphenidate (control, 1 mg/kg/day) tablets, two times a day. The patients were examined at baseline and14, 28, 42, and 56 days after the start of treatment. |

Both groups were clinically effective in the improvement of ADHD. However, | P. incarnata | was inferior to methylphenidate in decreasing anxiety and nervousness. | [22] | ||||||||||||

| Aromatherapy essential oils ( | M. spicata | , | M. piperita | , | Z. officinale | , and | L. angustifolia | ) | Pilot randomized controlled trial, 39 patients with age range of 4–16 years with postoperative nausea and vomiting were selected for the trial. |

Children were treated with a single placebo or aromatherapy. | Non-significant improvement of postoperative nausea and vomiting with aromatherapy. Though the preparation has been recommended for large-scale randomized clinical trials. |

[23] |

3. Safety Aspects of Childhood Supplementation

Safety Aspects of Childhood Supplementation

43. Conclusions

References

- Dwyer, J.; Nahin, R.L.; Rogers, G.T.; Barnes, P.M.; Jacques, P.M.; Sempos, C.T.; Bailey, R. Prevalence and predictors of children’s dietary supplement use: The 2007 National Health Interview Survey. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 97, 1331–1337.

- Bailey, R.L.; Gahche, J.J.; Thomas, P.R.; Dwyer, J.T. Why US children use dietary supplements. Pediatr. Res. 2013, 74, 737–741.

- Robinson, M.M.; Zhang, X. Traditional medicines: Global situation, issues and challenges. World Med. Situat. 2011, 3, 1–14.

- Wegener, T. Herbal medicinal products in the paediatric population—Status quo and perspectives. Wien. Med. Wochenschr. 2013, 163, 46–51.

- Çiftçi, S.; Samur, F.G. Use of botanical dietary supplements in infants and children and their effects on health. Hacet. Üniv. Sağlık Bilim. Fak Derg. 2017, 4, 30–45.

- Kamboj, V.P. Herbal medicine. Curr. Sci. 2000, 78, 35–39.

- Uchida, K.; Inoue, M.; Otake, K.; Koike, Y.; Kusunoki, M. Complementary and alternative medicine use by Japanese children with pediatric surgical diseases. Open J. Pediatr. 2013, 3, 49–53.

- Zhang, Y.; Fein, E.B.; Fein, S.B. Feeding of dietary botanical supplements and teas to infants in the United States. Pediatrics 2011, 127, 1060–1066.

- Pitetti, R.; Singh, S.; Hornyak, D.; Garcia, S.E.; Herr, S. Complementary and alternative medicine use in children. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2001, 17, 165–169.

- Katz, M.; Adar Levine, A.; Kol-Degani, H.; Kav-Venaki, L. A compound herbal preparation (CHP) in the treatment of children with ADHD: A randomized controlled trial. J. Atten. Disord. 2010, 14, 281–291.

- Tavares-Silva, C.; Holandino, C.; Homsani, F.; Luiz, R.R.; Prodestino, J.; Farah, A.; de Paula Lima, J.; Simas, R.C.; Castilho, C.V.V.; Leitão, S.G. Homeopathic medicine of Melissa officinalis combined or not with Phytolacca decandra in the treatment of possible sleep bruxism in children: A crossover randomized triple-blinded controlled clinical trial. Phytomedicine 2019, 58, 152869.

- Alexandrovich, I.; Rakovitskaya, O.; Kolmo, E.; Sidorova, T.; Shushunov, S. The effect of fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) seed oil emulsion in infantile colic: A randomized, placebo-controlled study. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 2003, 9, 58.

- Martinelli, M.; Ummarino, D.; Giugliano, F.; Sciorio, E.; Tortora, C.; Bruzzese, D.; De Giovanni, D.; Rutigliano, I.; Valenti, S.; Romano, C. Efficacy of a standardized extract of Matricariae chamomilla L., Melissa officinalis L. and tyndallized Lactobacillus acidophilus (HA 122) in infantile colic: An open randomized controlled trial. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2017, 29, e13145.

- Javid, A.; Haghi, N.M.; Emami, S.A.; Ansari, A.; Zojaji, S.A.; Khoshkhui, M.; Ahanchian, H. Short-course administration of a traditional herbal mixture ameliorates asthma symptoms of the common cold in children. Avicenna J. Phytomed. 2019, 9, 126.

- Janssen, G.; Bode, U.; Breu, H.; Dohrn, B.; Engelbrecht, V.; Göbel, U. Boswellic acids in the palliative therapy of children with progressive or relapsed brain tumors. Klin. Padiatr. 2000, 212, 189–195.

- Müller, S.; Klement, S. A combination of valerian and lemon balm is effective in the treatment of restlessness and dyssomnia in children. Phytomedicine 2006, 13, 383–387.

- Razlog, R.; Pellow, J.; White, S.J. A pilot study on the efficacy of Valeriana officinalis mother tincture and Valeriana officinalis 3X in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Health SA Gesondheid 2012, 17, 1–7.

- Canciani, M.; Murgia, V.; Caimmi, D.; Anapurapu, S.; Licari, A.; Marseglia, G.L. Efficacy of Grintuss® pediatric syrup in treating cough in children: A randomized, multicenter, double blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2014, 40, 56.

- Cohen, H.A.; Hoshen, M.; Gur, S.; Bahir, A.; Laks, Y.; Blau, H. Efficacy and tolerability of a polysaccharide-resin-honey based cough syrup as compared to carbocysteine syrup for children with colds: A randomized, single-blinded, multicenter study. World J. Pediatr. 2017, 13, 27–33.

- Carnevali, I.; La Paglia, R.; Pauletto, L.; Raso, F.; Testa, M.; Mannucci, C.; Sorbara, E.E.; Calapai, G. Efficacy and safety of the syrup “KalobaTUSS®” as a treatment for cough in children: A randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. BMC Pediatr. 2021, 21, 29.

- Trompetter, I.; Krick, B.; Weiss, G. Herbal triplet in treatment of nervous agitation in children. Wien. Med. Wochenschr. 2013, 163, 52–57.

- Akhondzadeh, S.; Mohammadi, M.; Momeni, F. Passiflora incarnata in the treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Clin. Pract. 2005, 2, 609.

- Kiberd, M.B.; Clarke, S.K.; Chorney, J.; d’Eon, B.; Wright, S. Aromatherapy for the treatment of PONV in children: A pilot RCT. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 16, 450.

- Gardiner, P. Dietary supplement use in children: Concerns of efficacy and safety. Am. Fam. Physician 2005, 71, 1068.

- Misra, S.M. Integrative therapies and pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: The current evidence. Children 2014, 1, 149–165.

- Woolf, A.D. Herbal remedies and children: Do they work? Are they harmful? Pediatrics 2003, 112, 240–246.

- Saper, R.B.; Kales, S.N.; Paquin, J.; Burns, M.J.; Eisenberg, D.M.; Davis, R.B.; Phillips, R.S. Heavy metal content of ayurvedic herbal medicine products. JAMA 2004, 292, 2868–2873.

- Bianco, M.I.; Lúquez, C.; de Jong, L.I.; Fernández, R.A. Presence of Clostridium botulinum spores in Matricaria chamomilla (chamomile) and its relationship with infant botulism. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2008, 121, 357–360.

- Bagheri, H.; Broué, P.; Lacroix, I.; Larrey, D.; Olives, J. Fulminant hepatic failure after herbal medicine ingestion in children. Thérapie 1998, 53, 82–83.