Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 3 by Beatrix Zheng and Version 2 by Beatrix Zheng.

Adaptive behaviour is defined as “the effectiveness with which the individual copes with the natural and social demands of his environment”. Such skills in daily functioning are essential for personal and social autonomy and are particularly crucial for individuals with intellectual disabilities, (ID) when cognitive testing is difficult, allowing us to evaluate their mastery of the daily environment.

- Down syndrome

- adaptive behaviour

- surplus effect

- Vineland Adaptive Behaviour Scales

- inclusive schooling

- early treatment programmes

- parental education

1. Introduction

Vianello et al. [1] defined the “surplus effect” as performance above the average compared to the expected potential on the basis of mental age. However, daily life performance in ID is not only determined by intrinsic factors such as cognitive and linguistic abilities, as motivation and efficacy are also influenced by external factors. The presence of strangers, for example, and the dependence on a familiar adult person have been found to exert a negative influence [2], whereas educational programmes and inclusive schooling have been shown to foster the surplus effect [1][3][4][5].

For genetic syndromes such as DS, a large variability in adaptive behaviour exists [6], indicating that development is not only determined by genetics, but also by other factors (e.g., early, tailored rehabilitative programs, schooling, and occupational programmes [7]). Adaptive behaviour in individuals with Down syndrome (DS) typically shows a specific phenotypic profile with points of strength in self-care, daily living skills, and socialisation, and a point of weakness in reception [8]: adaptive skills are generally higher than cognitive and language abilities, and they continued to improve with age [9][10], even past the time when cognitive abilities have usually reached a plateau [11].

The few previous studies that examined the effect of early treatment programmes in childhood [12] on DS outcomes showed no early change in adaptive skills in childhood, and slowly increasing adaptive skills until middle adulthood [11]. In September 1978 (Legge no. 517/1977), inclusive schooling started to become mandatory for all children in Italy, obliging teachers to develop specific and individual treatment and educational programmes for each child with ID. Furthermore, the presence of a support teacher with the child in class also became mandatory.

In the current analysis, we sought to study the impact of inclusive schooling, parental educational levels, and early treatment programmes on adaptive functioning in DS adulthood. We hypothesised that school inclusion promotes the surplus effect of adaptive behaviour in DS adulthood. Secondarily, we hypothesised that age, early treatment programmes, and parental educational levels would additionally enhance the surplus effect.

2. Analysis on Results

2.1. Participants’ Characteristics

Fifty-four DS individuals were included (22 females) with a mean age of 28.6 ± 8.8 (min. 19 to max. 52.3 years). Thirty-five individuals were under 30 years old, while the remaining 19 participants were all above 30 years of age. All individuals showed the clinical phenotype of DS; in 51 individuals, clinical diagnosis was confirmed by cytogenetic analysis where 43 individuals (79.6%) showed complete Trisomy 21, and eight individuals (14.8%) showed mosaic DS. Cytogenetic analysis could not be performed on the three remaining individuals (5.6%) because of their refusal of blood withdrawal.

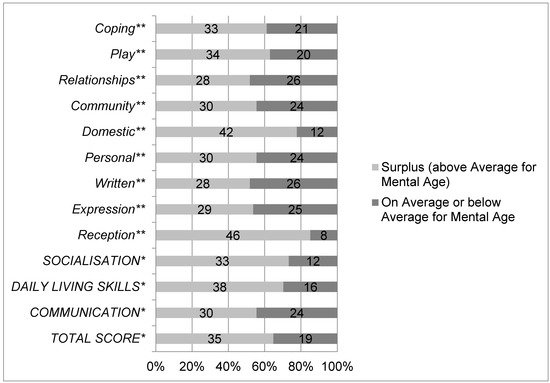

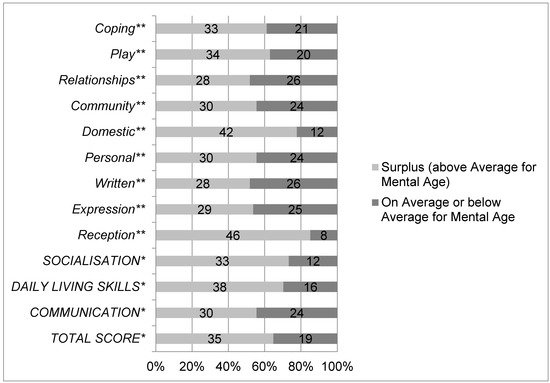

The majority of individuals showed a surplus effect regarding their overall level of adaptive behaviour (35/54, 65%) as well as in all the main domains and subdomains (Figure 1). The main domain of socialisation showed the highest mean equivalent age (Table 1). Within the subdomains, the highest mean equivalent ages were seen in domestic skills and coping strategies (mean 9.9 ± 3.3, min. 3.3–max. 16.9; mean 8.3 ± 3.6, min. 3.0–max. 15.3, respectively). Cognitive testing by CPM (in one individual with Leiter Scales) could be performed in 48 individuals. The remaining six participants were not testable by CPM or Leiter Scales and were classified as profound ID. By virtue of the small numbers in the profound and severe ID groups, these two groups were put together. Individuals were hence divided into three groups of ID (mild, moderate, and severe ID). The mean intelligence quotient (IQ) was 51.3 ± 12.2 (min. 30.0, max. 80.0); mean equivalent mental age at the 50th percentile was 5.2 ± 1.8 (min. 3.0; max 10.0 years). Seventeen individuals belonged to the mild ID-group (32%), 19 (35%) to the moderate ID-group, and 18 (33%) to the severe ID-group.

Figure 1. Proportion of individuals with DS (n = 52) who do (light grey) or do not (dark grey) exhibit a surplus effect on main domains * (communication, daily living skills, socialisation) and subdomains ** of adaptive behaviour (reception, expression, written, personal, domestic, community, relationships, play, and coping) and the adaptive behaviour composite * (total score). * Main domains and total score are written in capital letters. ** Subdomains are written in italic letters.

Table 1. Mean equivalent ages of adaptive behaviour in DS individuals on main domains, total score and mean mental age (in years).

| Mean Age * | Standard Deviation | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|

shows the primary and secondary endpoints comparing participants with inclusive schooling with participants without inclusive schooling.

Table 3. Proportion of DS individuals with a surplus effect * in adaptive behaviour divided by inclusive and non-inclusive schooling (adjusted for gender and maternal education by regression).

| Number of Individuals with SURPLUS *, n (%) | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p-Value | Odds Ratio MODEL 1 (gender) | 95% CI | p-Value | Odds Ratio MODEL 3 (Gender & Maternal Education) | 95% CI | p-Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adaptive Skills | ||||||||||||||

| Adaptive Behaviour | Inclusive schooling Yes (n = 46)/ No (n = 8) | |||||||||||||

| Communication | 7.0 | 3.4 | 1.0 | 13.0 | ||||||||||

| Total Score | 32 (70%)/3 (28%) | 3.8 | 0.8–18 | 0.090 | 16.4 | 1.3–206 | 0.030 | Daily Living Skills | 7.3 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 13.0 | ||

| Socialisation | 7.3 | 4.3 | 1.7 | 16.9 | ||||||||||

| 14.9 | 1.1–194 | 0.039 | ||||||||||||

| Main Domains | Total score | 7.1 | 3.2 | 1.7 | 13.9 | |||||||||

| Mental age | 5.2 | 1.8 | 3.0 | 10.0 |

* Mean age in years. Bold numbers highlight the highest level of equivalent age in the domain socialisation.

In total, 46/54 (85%) participants attended inclusive schools: 42/54 (77%) with immediate inclusion at school start, and 4/54 (7%) children during the last two years of elementary school. The remaining 8/54 (15%) did not attend inclusive schools: five (9%) never attended any school or treatment program, and three (6%) attended special schools.

Table 2 shows the relevant baseline characteristics split for groups with and without inclusive schooling. Statistically significant differences were observed for age, mental age, total school years, years of maternal and paternal schooling, and the duration of speech and of psychomotor therapy. With respect to these factors, participants with inclusive schooling were significantly younger, showing a substantially higher mental age and a remarkably higher number of attended school years for themselves as well as for both parents, and a significantly higher number of years of speech and psychomotor therapy (Table 2).

Table 2. Patient characteristics in DS individuals who attended (light grey) or did not attend (white) inclusive schooling.

| Communication | ||||||||||

| 27 (59%)/3 (38%) | 2.4 | 0.5–11 | 0.443 | 4.1 | 0.5–35.5 | 0.203 | 3.6 | 0.4–32.9 | 0.256 | |

| Daily Living Skills | 33 (72%)/5 (63%) | 1.5 | 0.3–7 | 0.682 | 3.9 | 0.4–40.8 | 0.255 | 3.9 | 0.4–41.9 | 0.682 |

| Socialisation | 31 (68%)/2 (25%) | 6.2 | 1.1–34 | 0.045 | 8.9 | 0.8–100 | 0.077 | 7.7 | 0.6–91.6 | 0.106 |

| Subdomains | ||||||||||

| Reception | 40 (87%)/6 (75%) | 2.2 | 0.3–13 | 0.588 | 0.9 | 0.1–12.2 | 0.908 | 0.8 | 0.06–11.6 | 0.873 |

| Expression | 26 (57%)/3 (38%) | 2.2 | 0.9–10 | 0.449 | 1.7 | 0.2–13.9 | 0.629 | 1.1 | 0.1–11.2 | 0.449 |

| Written | 27 (59%)/1 (13%) | 9.9 | 1.1–87 | 0.022 | 9.1 | 0.6–129 | 0.102 | 7.4 | 0.5–114 | 0.150 |

| Personal Skills | 26 (57%)/4 (50%) | 1.3 | 0.3–6 | 1.000 | 1.8 | 0.2–14.5 | 0.596 | 1.6 | 0.2–13.6 | 0.656 |

| Domestic Skills | 35 (76%)/7 (88%) | 0.5 | 0.5–4 | 0.667 | 0.5 | 0.03–7.4 | 0.583 | 0.4 | 0.02–6.6 | 0.520 |

| Community | 29 (63%)/1 (13%) | 11.9 | 1.3–105 | 0.016 | 28.4 | 1.6–506 | 0.023 | 27.7 | 1.5–500 | 0.016 |

| Interpersonal Relations | 26 (57%)/4 (50%) | 3.9 | 0.7–21 | 0.135 | 3.3 | 0.3–30.8 | 0.328 | 2.7 | 0.3–27.5 | 0.401 |

| Play | 31 (67%)/3 (38%) | 3.4 | 0.7–16 | 0.130 | 14.4 | 1.2–172 | 0.036 | 12.9 | 1.0–169 | 0.050 |

| Coping skills | 29 (63%)/4 (50%) | 1.7 | 0.4–7 | 0.697 | 1.3 | 0.2–10.4 | 0.823 | 0.9 | 0.1–8.4 | 0.943 |

| Inclusive Schooling Yes ( |

|---|

| n | = 46) | Inclusive Schooling No (n = 8) |

Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, in years * | 26.2 ± 6.3 | 43 ± 7.3 | <0.001 |

| Female ** | 17 (37%) | 5 (63%) | 0.248 |

| Mental age, in years * | 5.5 ± 1.8 | 3.6 ± 0.8 | 0.020 |

| Total school years *, *** | 11.4 ± 2.3 | 1.5 ± 3 | <0.001 |

| Years of inclusive school * | 10.3 ± 3.4 | 0 ± 0.0 | <0.001 |

| Mother’s years of schooling * | 8.8 ± 4.7 | 2.6 ± 3.8 | 0.001 |

| Father’s years of schooling * | 8.8 ± 4.6 | 2.9 ± 2.5 | 0.001 |

| Duration of speech therapy * | 5.4 ± 4.2 | 0.3 ± 0.7 | 0.001 |

| Duration of psychomotor therapy * | 3.8 ± 4.2 | 0.5 ± 1.4 | 0.034 |

| Duration of pedagogic therapy * | 2.4 ± 4.4 | 0.6 ± 1.8 | 0.262 |

| Current day time activity outside of home, days/week * | 4.4 ± 1.5 | 4.4 ± 1.8 | 0.919 |

| Living in a city > 100.000 dwellers ** | 19 (41%) | 2 (25%) | 0.383 |

| Living in a city < 100.000 dwellers ** | 27 (59%) | 6 (75%) | 0.383 |

* mean, SD. ** n, %; For frequencies with Chi-square and Fisher’s exact test were used. *** Including, inclusive, and “special” school years. Bold numbers highlight significance level p < 0.001.

Table 3

* Surplus has been defined as the effect when an individual performs above the average as compared to the expected potential on the basis of mental age (Vianello et al. 2006). Proportions were calculated by Fisher’s exact test. Bold numbers highlight significance level p < 0.050. Light grey indicate percentages of inclusive schooling. Description: The primary endpoint was adjusted in a multivariate logistic regression model for (1) gender (model 1), (2) gender and paternal education (model 2) (data not shown), and (3) gender and maternal education (model 3). Adjusted for gender, DS individuals with inclusive schooling showed 16.4 times higher odds for a surplus effect on the total score of adaptive behaviour (primary endpoint); adjusted for gender and maternal education DS individuals with inclusive schooling showed 14.9 higher odds. Adjusted for gender, DS individuals with inclusive schooling showed 28.4 times higher odds for a surplus effect in the subdomain community and 14.4 times higher odds in the subdomain play. This was also observed when adjusted for gender and paternal education in the subdomain community (OR 22.3) and when adjusted for gender and maternal education (Table 3) in the subdomains community and play (Table 3).

2.2. Primary Endpoint

For the overall level of adaptive behaviour, we observed a higher percentage of participants with a surplus in individuals with inclusive schooling as opposed to those without inclusive schooling (69.5% vs. 37.5%; p = 0.090), probably not significant due to the small sample size (Table 3).

The percentage of the surplus effect was higher in females than in males (73% versus 59%; p = 0.391, odds ratio 0.548 CI 0.17–1.8), however, not significantly. When looking at participants without inclusive schooling (five females and three males), three females showed a surplus effect in adaptive behaviour, while no male participant displayed this characteristic (p = 0.196). However, the significance can be interpreted ambiguously due to the small sample size. When comparing males with inclusive schooling to males without inclusive schooling, 65% of males with inclusive schooling showed a surplus effect while none of the males without inclusive schooling adhered to the pattern (p = 0.058).

Therefore, we adjusted the multivariate logistic regression model for (1) gender, (2) gender and paternal education (data not shown), and (3) gender and maternal education (Table 3).

The surplus effect in the DS individuals with inclusive schooling reached statistical significance adjusted for gender (p = 0.03) and adjusted for gender and for maternal educational level (p = 0.039), and showed a trend adjusted for gender and for paternal education (p = 0.085).

2.3. Secondary Endpoints

Secondary endpoints were the proportions of a surplus effect in the main domains and subdomains of adaptive behaviour in DS individuals with and without inclusive schooling. Individuals with inclusive schooling showed higher proportions of a surplus effect in all main domains and subdomains except in domestic skills. Significantly higher percentages of the surplus effect were observed for individuals with inclusive schooling in the main domain socialisation (p = 0.045), and in the subdomains written (p = 0.022) and community (p = 0.016).

After adjustment (Table 3) in the multivariate logistic regression model, the surplus effect in the domain socialisation showed a trend pertaining to gender (p = 0.077), and was significant in the subdomain community adjusted for gender (p = 0.023), for gender and paternal educational level (p = 0.039), and for gender and maternal educational level (p = 0.025). In the subdomain written, no significant differences were observed in the multivariate regression model. However, after adjustment, a higher percentage of surplus effect was observed in the subdomain play when adjusted for gender (p = 0.036) as well as for gender and maternal education (p = 0.051).

3. Current Insights

In our study, we investigated the influence of inclusive schooling in childhood on the surplus effect of adaptive behaviour in DS adults as well as factors promoting this surplus effect. Adaptive behaviour in DS has been described as being higher than could be expected from cognitive abilities [3][13][14]. This phenomenon, first defined by Vianello and co-workers [3][13] as the surplus effect, does not only indicate a syndrome-specific phenotype, but also reveals how appropriate educational interventions and therapy programmes facilitate above average individual performance [1].

In the past, we found that DS-individuals with mild to moderate levels of ID performed significantly more often above the average than individuals with severe ID [11]. However, age equivalents of adaptive behaviour were higher than mental age in all age-groups. To study adaptive behaviour without the effect of cognition, the comparison of adaptive levels above the average (surplus effect) were referenced within their own ID-group.

The majority of DS individuals attended inclusive schools and showed a surplus effect in adaptive behaviour on the overall adaptive behaviour level as well as on all the main domains and subdomains. DS adults with inclusive schooling were significantly younger, showed a higher mental age, had attended school for a longer period of time, and had attended a higher number of years in early treatment programmes than DS adults having attended no inclusive schooling (i.e., special schooling) or even no schooling at all. Moreover, parental educational levels were significantly higher in individuals with inclusive schooling. Furthermore, female gender and parental, especially maternal educational levels significantly enhanced the surplus effect.

References

- Vianello, R.; Lanfranchi, S. Positive effects of the placement of students with intellectual developmental disabilities in typical class. Life Span Disabil. 2011, 14, 75–84.

- Zigler, E.; Benett-Gates, D. Personality Development in Individuals with Mental Retardation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999.

- Vianello, R.; Lanfranchi, S. Genetic syndromes causing mental retardation: Deficit and surplus in school performance and social adaptability compared to cognitive functioning. Life Span Disabil. 2009, 12, 41–52.

- Hardiman, S.; Guerin, S.; Fitzsimons, E. A comparison of the social competence of children with moderate intellectual disability in inclusive versus segregated school settings. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2009, 30, 397–407.

- Scruggs, T.E.; Michaud, K. The “Surplus” Effect in Developmental Disability: A Function of Setting or Training (or Both)? Life Span Disabil. 2009, 2, 141–149.

- Hodapp, R.M. Direct and indirect behavioural effects of different genetic disorders of mental retardation. Am. J. Ment. Retard. 1997, 102, 67–79.

- Hines, S.A.; Bennett, F. Effectiveness of early intervention for children with Down syndrome. Ment. Retard. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 1996, 2, 96–101.

- Dykens, E.M.; Hodapp, R.M.; Evans, D.W. Profiles and development of adaptive behavior in children with Down syndrome. Am. J. Ment. Retard. 1994, 98, 580–587.

- Rondal, J.A. Cases of exceptional language in mental retardation and Down syndrome: Explanatory perspectives. Downs Syndr. Res. Pr. 1998, 5, 1–15.

- Hodapp, R.M.; Urbano, R.C.; So, S.A. Using an epidemiological approach to examine outcomes affecting young children with Down syndrome and their families. Downs Syndr. Res. Pr. 2006, 10, 83–93.

- Dressler, A.; Perelli, V.; Feucht, M.; Bargagna, S. Adaptive behaviour in Down syndrome: A cross-sectional study from childhood to adulthood. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2010, 122, 673–680.

- Iarocci, G.; Virji-Babul, N.; Reebye, P. The Learn at Play Program (LAPP): Merging Family, Developmental Research, Early Intervention, and Policy Goals for Children with Down Syndrome. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 2006, 3, 11–21.

- Vianello, R. La Sindrome di Down. Sviluppo Psicologico e Integrazione Dalla Nascita All’età Senile; Junior: Bergamo, Italy, 2006.

- Dressler, A.; Bozza, M.; Perelli, V.; Tinelli, F.; Guzzetta, A.; Cioni, G.; Bargagna, S. Vision problems in Down syndrome adults do not hamper communication, daily living skills and socialisation. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2015, 127, 594–600.

More