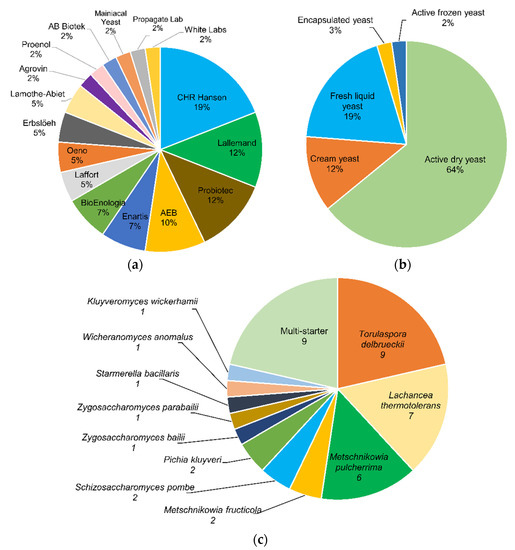

About 42 commercial products based on non-Saccharomyces yeasts are estimated as available on the market, being mostly pure cultures (79%), with a predominance of Torulaspora delbrueckii, Lachancea thermotolerans, and Metschnikowia pulcherrima. The others are multi-starter consortia that include non-Saccharomyces/Saccharomyces mixtures or only non-Saccharomyces species. Several commercial yeasts have shown adequate biocompatibility with S. cerevisiae in mixed fermentations, allowing an increased contribution of metabolites of oenological interest, such as glycerol, esters, higher alcohols, acids, thiols, and terpenes, among others, in addition to a lower production of acetic acid, volatile phenols, biogenic amines, or urea. The studies conducted to date demonstrate the potential of these yeasts to improve the properties of wine as an alternative and complement to the traditional S. cerevisiae.

- commercial non-Saccharomyces yeasts

- winemaking

- biocompatibility

- wine quality

Note: The entry will be online only after author check and submit it.

1. Introduction

2. Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts Available on the Market

| Yeast Species | Commercial Brand | Providing Company (Country) | Format |

|---|---|---|---|

| Torulaspora delbrueckii | Biodiva TD291 | Lallemand (Canada) | ADY |

2.2. Lachancea Thermotolerans

| Commercial Yeast | Level | Fermentation | TYPE OF WINE | Changes with Respect to | S. cerevisiae | Sensory Impact with Respect to | S. cerevisiae | Reference | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Torulaspora delbrueckii | Biodiva TD291 (Lallemand, Montreal, QC, Canada) |

Semi-industrial (Two wineries: 150 and 250 L) |

Sequential and simultaneous | + | S. cerevisiae | Lalvin EC1118 (Lallemand, Montreal, QC, Canada) | Amarone (Corvina, Rondinella, and Corvinone red grapes) |

↑ 2-phenylethanol; ethyl butyrate, ethyl lactate, isoamyl lactate; 4-carbethoxy-γ-butyrolactone, sherry lactones; α-terpineol, Ho-diendiol I, and endiol ↓ isoamyl acetate |

Higher aroma intensity, fruitiness, sweetness, ripe red fruit (cherry) | [9] | [8] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Torulaspora delbrueckii | Prelude | Biodiva TD291 (Lallemand, Montreal, QC, Canada) | CHR Hansen (Denmark) | Laboratory | Sequential | + | S. cerevisiae | 734 * | ADY | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gewürztraminer | ↑ linalool (OAV ≈ 1.0) | ↓ citronellol and geraniol | Higher overall score (balance between terpenes) | [ | 20] | [19] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Torulaspora delbrueckii | Zymaflore Alpha | Zymaflore Alpha | Laffort (France) | (Laffort, Bordeaux, France) | Torulaspora delbrueckii | ADY | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Biodiva TD291 (Lallemand, Montreal, QC, Canada) |

Semi-industrial (150 L) |

Sequential | + | S. cerevisiae | Lalvin EC1118 (Lallemand, Montreal, QC, Canada) | Soave (Garganega white grape) and Chardonnay |

↑ 2-phenylethanol; diethyl succinate ↓ 4-vinylguaiacol and 4-vinylphenol: with Alpha in both wines (4-vinylguaiacol OAV < 1.0) ↓ isoamyl acetate: Soave wine with Alpha; Chardonnay wine with Alpha and Biodiva) |

Both wines: higher aroma intensity and persistence, complexity, and body Better floral and tropical fruit attributes (especially in Soave wine) |

[10] | [9] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Torulaspora delbrueckii | Viniferm NSTD | Biodiva TD291 (Lallemand, Montreal, QC, Canada) | Agrovin (Spain) | Laboratory (500 mL) |

Sequential | + | ADY | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| S. cerevisiae | Lalvin EC1118 (Lallemand, Montreal, QC, Canada) | Santo | (Sweet white wine from Nosiola grape) |

↑ 2-phenylethanol; ethyl lactate; sherry lactones ↓ 4-vinylphenol and 4-vinylguaiacol ↓ isoamyl acetate ↑ 3-methylthio-1-propanol |

Sensory analysis not performed | EnartisFerm Qτ | Enartis (Italy) | ADY | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [ | 10 | ] | [ | 9 | ] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Torulaspora delbrueckii | Zymaflore Alpha (Laffort, Bordeaux, France) |

Laboratory (1.2 L) |

Sequential and simultaneous | + | S. cerevisiae | Zymaflore X5 (Laffort, Bordeaux, France) | Sauvignon Blanc | ↑ isoamyl acetate (OAV > 1.0), isobutyl acetate, 2-phenylethyl acetate, ethyl isobutyrate, ethyl propanoate, ethyl dihydroxycinnamate | Sensory analysis not performed | [11] | [10] | EnartisFerm Qτ Liquido | Enartis (Italy) | CRY | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Torulaspora delbrueckii | Zymaflore Alpha (Laffort, Bordeaux, France) |

Semi-industrial (150 L) |

Sequential | + | S. cerevisiae | Zymaflore FX10 (Laffort, Bordeaux, France) | Merlot | ↑ isoamyl acetate (OAV > 1.0), ethyl isobutyrate (OAV > 1.0), isobutyl acetate, ethyl propanoate, ethyl dihydroxycinnamate | Higher complexity and fruity notes (interaction between esters) | [11] | [10] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Torulaspora delbrueckii | Biodiva TD291 (Lallemand, Montreal, QC, Canada) | Lachancea thermotolerans | Concerto (CHR Hansen, Hørsholm, Denmark) | Metschnikowia | pulcherrima | Flavia MP346 | Oenovin Torulaspora BIO | Oeno (Italy) | ADY | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (Lallemand, Montreal, QC, Canada) | Laboratory (60 mL) |

Monoculture | Must/wine analyzed in the initial stages of the fermentation (2.0–3.0% | v/v | ethanol) | Sauvignon Blanc and Syrah |

Wines produced with T. delbrueckii: | ↑ phenethyl propanoate (>50 times in both wines); linalool (both wines), β-damascenone (Sauvignon Blanc wine) | Wines produced with L. thermotolerans: | ↑ in both wines: 2-phenylethanol; phenethyl propanoate, other esters; nerol, terpinen-4-ol ↑ in both wines: 3-methylthio-1-propanol | Wines produced with M. pulcherrima: | ↑ phenethyl propanoate, phenethyl butyrate, isoeugenil phenylacetate (Syrah wine); linalool (Syrah wine); β-damascenone (Sauvignon Blanc wine) ↑ 2-methoxy-4-vinylphenol (both wines), 3-methylthio-1-propanol (Syrah wine) |

Sensory analysis not performed | [21] | [20] | Torulaspora delbrueckii | Probiotec (Italy) | FLY | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Torulaspora delbrueckii | Biodiva TD291 (Lallemand, Montreal, QC, Canada) | Metschnikowia pulcherrima | Flavia MP346 (Lallemand, Montreal, QC, Canada) |

Semi-industrial (100 L) |

Sequential | + | S. cerevisiae | QA23 (Lallemand, Montreal, QC, Canada) | Base wine for Cava (Macabeo grape) |

Wine produced with T. delbrueckii: | ↑ glycerol ↑ foamability: Hm > 17%, foam persistence: Hs > 20% ↓ volatile acidity ↑ 4-ethylguaiacol, 4-ethylphenol, 4-vinylphenol | Wine produced with M. pulcherrima: | ↑ foam persistence: Hs > 35% ↓ esters ↑ 4-ethylguaiacol, 4-vinylphenol, 2-methoxyphenol, 2,6-dimethoxyphenol (2,6-dimethoxyphenol: OAV > 1.0, smoky aroma) |

Higher preference for wine produced with | T. delbrueckii | (more similar to the control) Higher smoky and floral notes in wine produced with | M. pulcherrima | [12] | [11] | Torulaspora delbrueckii 12.2 | Probiotec (Italy) | FLY | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Lachancea thermotolerans | Concerto (CHR Hansen, Hørsholm, Denmark) | Metschnikowia | pulcherrima | Flavia MP346 (Lallemand, Montreal, QC, Canada) | Pichia kluyveri | FrootZen (CHR Hansen, Hørsholm, Denmark) |

Laboratory (5 L) |

Sequential | + | S. cerevisiae | Lalvin EC1118 (Lallemand, Montreal, QC, Canada) | Riesling | Wine produced with L. thermotolerans: | ↑ lactic acid; ethyl esters; terpenes |

Lachancea thermotolerans | Laktia | Lallemand (Canada) | ADY | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Concerto | CHR Hansen (Denmark) | ADY | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 22 | ] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lachancea thermotolerans | Octave | Viniflora Concerto (CHR Hansen, Hørsholm, Denmark) | CHR Hansen (Denmark) | Laboratory | ADY | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (5 L) | Sequential | + | Schizosaccharomyces pombe | V2 * or | Sequential | + | S. cerevisiae | 88 * | Tempranillo | ↑ lactic acid and pyruvic acid (>2.0 and >3.7, respectively, respect to AF + MLF) ↑ vitisin A and vitisin B (>1.5 and >2.6, respectively, respect to AF + MLF) ↑ total anthocyanins (>1.6 respect to AF + MLF) | S. pombe | : residual urea (97% lower than AF + MLF) | L. thermotolerans/S. pombe | Higher acidity Higher aroma intensity and quality, sensory acceptability |

[17] | [16] | EnartisFerm Qƙ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Metschnikowia pulcherrima | AWRI Obsession (AB Biotek, London, United Kingdom) |

Semi-industrial | Enartis (Italy) | (50 kg of grape) | Simultaneous | CRY | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| + | S. cerevisiae | AWRI838 | Merlot | ↓ alcohol degree ( < 1.0% | v/v | ) ↑ total esters; higher alcohols ↑ sulfur compounds: H | 2 | S (>22 times), dimethyl sulfide (>2.1 times), ethanethiol, methanethiol | High score: red fruits aroma and flavor and fruit in general Low score: vegetal, meat, and barnyard aromas |

[24] | [23] | Excellence X’Fresh | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Torulaspora delbrueckii | Zymaflore Alpha (Laffort, Bordeaux, France) | Torulaspora delbrueckii | Biodiva TD291 (Lallemand, Montreal, QC, Canada) | Torulaspora delbrueckii | Prelude (CHR Hansen, Hørsholm, Denmark) | Lamothe-Abiet (France) | Lachancea thermotolerans | Viniflora Concerto (CHR Hansen, Hørsholm, Denmark) | Metschnikowia | pulcherrima | Flavia MP346 (Lallemand, Montreal, QC, Canada) Melody ( | Torulaspora delbrueckii/Lachancea thermotolerans/Saccharomyces cerevisiae | ) | ADY | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

(CHR Hansen, Hørsholm, Denmark) |

Laboratory (20 L) |

Sequential | + | S. cerevisiae | PDM (Maurivin, Australia) and | Multi-starter | Melody |

Shiraz (Two different ripeness level: 24 and 29 °Brix) |

Wine produced from must of 24 °Brix: | ↓ alcohol degree: <0.6% | v/v | (multi-starter Melody) ↑ glycerol: >0.85 g/L (Concerto), >1.84 g/L (Flavia) ↑ isoamyl acetate (Prelude, Melody), 2-phenylethyl acetate and ethyl isobutyrate (Alpha, Biodiva, Prelude), isobutyl acetate (Prelude, Concerto, Melody) ↑ terpenes: Alpha, Biodiva, Prelude ↓ tannins: Alpha, Biodiva, Prelude, Concerto, Flavia | Wine produced from must of 29 °Brix: | ↑ 2-phenylethanol (mainly Alpha, Biodiva, Prelude; and to a lesser extent Concerto, Flavia, Melody) ↑ terpenes: Alpha, Biodiva, Prelude Residual sugars: >5 g/L (Alpha, Biodiva, Prelude) |

Wine produced from must of 24 °Brix: | Better aroma intensity, floral attribute, perception of red fruit (Melody, Biodiva, Alpha, Flavia) | Wine produced from must of 29 °Brix: | Sweetness (Alpha, Biodiva, Prelude) |

[2] | LEVULIA Alcomeno | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Metschnikowia | pulcherrima | AEB Group (Italy) | NS-EM-34 | ADY | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (Reported as pre-commercial strain by authors) | Laboratory (5 L) |

Sequential | + | S. cerevisiae | Viniferm Diana (Agrovin, Alcázar de San Juan, Spain) or | Sequential | + | S. cerevisiae | Viniferm Revelacion (Agrovin, Alcázar de San Juan, Spain) | Verdejo | M. pulcherrima/S. cerevisiae Diana: | ↓ alcohol degree: <0.62% | v/v | ↑ 4MSP (≈28 ng/L vs. ≈4 ng/L in | S. cerevisiae | Kluyveromyces thermotolerans | Probiotec (Italy) | FLY | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Metschnikowia pulcherrima | Flavia MP346 | Lallemand (Canada) | ADY | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oenoferm MProtect | Erbslöeh (Germany) | ADY | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| AWRI Obsession | AB Biotek (United Kingdom) | ADY | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| LEVULIA Pulcherrima | AEB Group (Italy) | ADY | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Primaflora VB BIO | AEB Group (Italy) | ADY | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Excellence B-Nature | Lamothe-Abiet (France) | ADY | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Metschnikowia fructicola | Levia Nature | Oeno (Italy) | ADY | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gaïa | Lallemand (Canada) | ADY | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Schizosaccharomyces pombe | Atecrem 12H | BioEnologia (Italy) | CRY | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Promalic | Proenol (Portugal) | ENY | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wicheranomyces anomalus | Anti Brett 1 | Probiotec (Italy) | FLY | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kluyveromyces wickerhamii | Anti Brett 2 | Probiotec (Italy) | FLY | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Starmerella bacillaris | Atecrem 11H | BioEnologia (Italy) | CRY | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ↓ 2-phenylethyl acetate; acetaldehyde | Wine produced with | M. pulcherrima | : | ↓ 2-phenylethanol, other higher alcohols; acetate esters; acetaldehyde | Wine produced with P. kluyveri: | ↑ 2-phenylethyl acetate ↓ isoamyl acetate; acetaldehyde |

All wines: higher preference and Riesling typicity; lower oxidation, acetaldehyde, and ethyl acetate perception Higher perception peach/apricot ( | L. thermotolerans | and | P. kluyveri | ), citrus/grapefruit ( | M. pulcherrima | ) | [16] | [15] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanseniaspora vineae | T02/5AF (from Uruguayan vineyards) |

Semi-industrial (100 L) |

Monoculture | Control: | S. cerevisiae | QA23 (Lallemand, Montreal, QC, Canada) | Macabeo | ↑ 2-phenylethyl acetate (50 times higher than | S. cerevisiae | ), isobutyl acetate, ethyl lactate; α-terpineol ↓ acetoin (73% lower than | S. cerevisiae | ) ↓ higher alcohols Synthesis of N-acetiltiramine and 1H-indole-3-ethanol acetate (not synthesized by | S. cerevisiae | ) | Higher preference, fruity, and floral scores | [22] | [21] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Torulaspora delbrueckii | Zymaflore Alpha (Laffort, Bordeaux, France) |

Laboratory (1.2 L) |

Sequential and simultaneous | control) ↑ glycerol (>0.72 g/L) ↓ higher alcohols | M. pulcherrima/S. cerevisiae Revelacion: | ↓ alcohol degree: <0.63% | v/v | ↑ 4MSP (≈28 ng/L vs. 0 ng/L in | S. cerevisiae | control) ↑ glycerol (>0.52 g/L) ↓ higher alcohols |

Both wines: highest scores in Verdejo typicity, fruity, intensity, and aromatic quality | [25] | [24] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanseniaspora vineae | (Currently under evaluation by Oenobrands, Montpellier, France) |

Semi-industrial (120 L) |

Monoculture | Control: | S. cerevisiae | Fermivin 3C (Oenobrands, Montpellier, France) | Albillo | ↑ esters, especially 2-phenylethyl acetate (OAV = 31.84) | Sensory analysis not performed | [26] | [25] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Torulaspora delbrueckii | Oenoferm Wild & Pure (Erbslöh, Geisenheim, Germany) | Metschnikowia | pulcherrima | Flavia MP346 (Lallemand, Montreal, QC, Canada) |

Laboratory (10 L) |

Sequential | + | S. cerevisiae | Oenoferm Bouquet (Erbslöh, Geisenheim, Germany) + | S. bayanus | LittoLevure CHA (Erbslöh, Geisenheim, Germany) | Sila | Decrease in alcohol degree | M. pulcherrima/S. bayanus/S. cerevisiae | : <0.91% | v/v | M. pulcherrima/S. bayanus | : <0.62% | v/v | Glycerol production | ( | S. cerevisiae | control: 5.7 g/L) | T. delbrueckii/S. bayanus | : 7.0 g/L | M. pulcherrima/S. bayanus/S. cerevisiae | : 6.7 g/L | Higher score of aroma and overall flavor: | M. pulcherrima/S. bayanus | and | T. delbrueckii/S. bayanus | Higher score: citrus flavor ( | M. pulcherrima/S. bayanus | ), melon and banana flavor ( | M. pulcherrima/S. cerevisiae | ) | [13] | [12] | ||||

| Torulaspora delbrueckii | Biodiva TD291 (Lallemand, Montreal, QC, Canada) | Metschnikowia pulcherrima | Flavia MP346 (Lallemand, Montreal, QC, Canada) |

Semi-industrial (50 L) |

Monoculture | Control: 3 commercial strains of | S. cerevisiae | Base wine for Cava (Chardonnay and Xarel.lo) |

Base wines with M. pulcherrima | High content of proteins. High foamability (Hm) and foam persistence (Hs) | Cava wines with T. delbrueckii | Highest concentrations of esters, especially ethyl isovalerate (120–126 µg/L) in both wines |

Cava wines | Better fruity and fresh aromatic profiles, especially with T. | delbrueckii | [8] | [7] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Torulaspora delbrueckii | Biodiva TD291 (Lallemand, Montreal, QC, Canada) | Metschnikowia pulcherrima | Flavia MP346 (Lallemand, Montreal, QC, Canada) | Hanseniaspora vineae | (Currently under evaluation by Oenobrands, Montpellier, France) | Lachancea thermotolerans | L31 * | Laboratory (1 L) |

Simultaneous at the beginning of fermentation | L. thermotolerans | + | T. delbrueckii | ; | L. thermotolerans | + | M. pulcherrima | ; | L. thermotolerans | + | H. vineae | + Addition on day 8: | S. cerevisiae | 7VA * | Airén | L. thermotolerans/M. pulcherrima | + | S. cerevisiae | ↑ lactic acid: up to 3.27 g/L ↓ pH: reduction to 3.42 (grape must 3.84) ↓ alcohol degree: <0.66% | v/v | (residual sugars = 0) ↑ higher alcohols; esters |

L. thermotolerans/M. pulcherrima | + | S. cerevisiae | Higher overall score Higher acidity |

[27] | [ | Zygosaccharomyces bailii | Fructoferm W3 | Lallemand (Canada) | ADY | ||

| Zygosaccharomyces parabailii | Hardened Spaniard | Mainiacal Yeast (United States) | FLY | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 26 | ] | Pichia kluyveri | Frootzen | CHR Hansen (Denmark) | AFY | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pichia kluveri MIP-001 | Propagate Lab (United States) | FLY | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pichia kluyveri + Kazachastania servazzii | Trillyeast | BioEnologia (Italy) | CRY | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Torulaspora delbrueckii + Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Oenoferm Wild & Pure | Erbslöeh (Germany) | ADY | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Torulaspora delbrueckii + Saccharomyces cerevisiae | New Nordic Ale Yeast | White Labs (United States) | FLY | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Torulaspora delbrueckii + Metschnikowia pulcherrima | Zymaflore Égide | Laffort (France) | ADY | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Metschnikowia pulcherrima + Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Primaflora VR BIO | AEB Group (Italy) | ADY | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lachancea thermotolerans + Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Symphony | CHR Hansen (Denmark) | ADY | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lachancea thermotolerans + Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Rhythm | CHR Hansen (Denmark) | ADY | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lachancea thermotolerans + Torulaspora delbrueckii + Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Harmony | CHR Hansen (Denmark) | ADY | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lachancea thermotolerans + Torulaspora delbrueckii + Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Melody | CHR Hansen (Denmark) | ADY |

2.1. Torulaspora Delbrueckii

| + | ||

| S. cerevisiae | ||

| Zymaflore X5 (Laffort, Bordeaux, France) | ||

| Sauvignon Blanc | ||

| ↑ aromatic thiols: 3SH and 3SHA | ||

| Sensory analysis not performed | ||

| [ | ||

| 23 | ] | [ |

2.3. Metschnikowia Pulcherrima

2.4. Pichia Kluyveri

2.5. Schizosaccharomyces Pombe

2.6. Hanseniaspora Vineae

3. Improvement in Fermentative Aromatic Profile Regarding Saccharomyces

3.1. Torulaspora Delbrueckii

3.2. Lachancea Thermotolerans

3.3. Metschnikowia Pulcherrima

3.4. Pichia Kluyveri

3.5. Hanseniaspora Vineae

3.6. Commercial Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts in Sparkling Wines

References

- Jolly, N.P.; Varela, C.; Pretorius, I.S. Not your ordinary yeast: Non-Saccharomyces yeasts in wine production uncovered. FEMS Yeast Res. 2014, 14, 215–237.

- Hranilovic, A.; Li, S.; Boss, P.K.; Bindon, K.; Ristic, R.; Grbin, P.R.; Van der Westhuizen, T.; Jiranek, V. Chemical and sensory profiling of Shiraz wines co-fermented with commercial non-Saccharomyces inocula. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2018, 24, 166–180.

- Petruzzi, L.; Capozzi, V.; Berbegal, C.; Corbo, M.R.; Bevilacqua, A.; Spano, G.; Sinigaglia, M. Microbial resources and enological significance: Opportunities and benefits. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 995.

- Morata, A.; Escott, C.; Bañuelos, M.A.; Loira, I.; Del Fresno, J.M.; González, C.; Suárez-lepe, J.A. Contribution of non-Saccharomyces yeasts to wine freshness. A review. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 34.

- Roudil, L.; Russo, P.; Berbegal, C.; Albertin, W.; Spano, G.; Capozzi, V. Non-Saccharomyces commercial starter cultures: Scientific trends, recent patents and innovation in the wine sector. Recent Pat. Food. Nutr. Agric. 2020, 11, 27–39.

- van Breda, V.; Jolly, N.; van Wyk, J. Characterisation of commercial and natural Torulaspora delbrueckii wine yeast strains. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2013, 163, 80–88.

- Mislata, A.M.; Puxeu, M.; Andorrà, I.; Espligares, N.; de Lamo, S.; Mestres, M.; Ferrer-Gallego, R. Effect of the addition of non-Saccharomyces at first alcoholic fermentation on the enological characteristics of Cava wines. Fermentation 2021, 7, 64.

- Azzolini, M.; Fedrizzi, B.; Tosi, E.; Finato, F.; Vagnoli, P.; Scrinzi, C.; Zapparoli, G. Effects of Torulaspora delbrueckii and Saccharomyces cerevisiae mixed cultures on fermentation and aroma of Amarone wine. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2012, 235, 303–313.

- Azzolini, M.; Tosi, E.; Lorenzini, M.; Finato, F.; Zapparoli, G. Contribution to the aroma of white wines by controlled Torulaspora delbrueckii cultures in association with Saccharomyces cerevisiae. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 31, 277–293.

- Renault, P.; Coulon, J.; de Revel, G.; Barbe, J.C.; Bely, M. Increase of fruity aroma during mixed T. delbrueckii/S. cerevisiae wine fermentation is linked to specific esters enhancement. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2015, 207, 40–48.

- González-Royo, E.; Pascual, O.; Kontoudakis, N.; Esteruelas, M.; Esteve-Zarzoso, B.; Mas, A.; Canals, J.M.; Zamora, F. Oenological consequences of sequential inoculation with non-Saccharomyces yeasts (Torulaspora delbrueckii or Metschnikowia pulcherrima) and Saccharomyces cerevisiae in base wine for sparkling wine production. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2015, 240, 999–1012.

- Puškaš, V.S.; Miljić, U.D.; Djuran, J.J.; Vučurović, V.M. The aptitude of commercial yeast strains for lowering the ethanol content of wine. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 1489–1498.

- Beckner Whitener, M.E.; Stanstrup, J.; Panzeri, V.; Carlin, S.; Divol, B.; Du Toit, M.; Vrhovsek, U. Untangling the wine metabolome by combining untargeted SPME-GCxGC-TOF-MS and sensory analysis to profile Sauvignon blanc co-fermented with seven different yeasts. Metabolomics 2016, 12, 53.

- Benito, Á.; Calderón, F.; Palomero, F.; Benito, S. Quality and composition of Airén wines fermented by sequential inoculation of Lachancea thermotolerans and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2016, 54, 135–144.

- Benito, S.; Hofmann, T.; Laier, M.; Lochbühler, B.; Schüttler, A.; Ebert, K.; Fritsch, S.; Röcker, J.; Rauhut, D. Effect on quality and composition of Riesling wines fermented by sequential inoculation with non-Saccharomyces and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2015, 241, 707–717.

- Benito, Á.; Calderón, F.; Benito, S. The combined use of Schizosaccharomyces pombe and Lachancea thermotolerans—Effect on the anthocyanin wine composition. Molecules 2017, 22, 739.

- Morata, A.; Gómez-Cordovés, M.C.; Calderón, F.; Suárez-Lepe, J.A. Effects of pH, temperature and SO2 on the formation of pyranoanthocyanins during red wine fermentation with two species of Saccharomyces. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2006, 106, 123–129.

- Vejarano, R.; Morata, A.; Loira, I.; González, M.C.; Suárez-Lepe, J.A. Theoretical considerations about usage of metabolic inhibitors as possible alternative to reduce alcohol content of wines from hot areas. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2013, 237, 281–290.

- Čuš, F.; Jenko, M. The influence of yeast strains on the composition and sensory quality of Gewürztraminer wine. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2013, 51, 547–553.

- Beckner Whitener, M.E.; Carlin, S.; Jacobson, D.; Weighill, D.; Divol, B.; Conterno, L.; Du Toit, M.; Vrhovsek, U. Early fermentation volatile metabolite profile of non-Saccharomyces yeasts in red and white grape must: A targeted approach. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 64, 412–422.

- Lleixà, J.; Martín, V.; del C. Portillo, M.; Carrau, F.; Beltran, G.; Mas, A. Comparison of fermentation and wines produced by inoculation of Hanseniaspora vineae and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 338.

- Renault, P.; Coulon, J.; Moine, V.; Thibon, C.; Bely, M. Enhanced 3-sulfanylhexan-1-ol production in sequential mixed fermentation with Torulaspora delbrueckii/Saccharomyces cerevisiae reveals a situation of synergistic interaction between two industrial strains. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 293.

- Varela, C.; Barker, A.; Tran, T.; Borneman, A.; Curtin, C. Sensory profile and volatile aroma composition of reduced alcohol Merlot wines fermented with Metschnikowia pulcherrima and Saccharomyces uvarum. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2017, 252, 1–9.

- Ruiz, J.; Belda, I.; Beisert, B.; Navascués, E.; Marquina, D.; Calderón, F.; Rauhut, D.; Santos, A.; Benito, S. Analytical impact of Metschnikowia pulcherrima in the volatile profile of Verdejo white wines. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 8501–8509.

- Del Fresno, J.M.; Escott, C.; Loira, I.; Herbert-Pucheta, J.E.; Schneider, R.; Carrau, F.; Cuerda, R.; Morata, A. Impact of Hanseniaspora vineae in alcoholic fermentation and ageing on lees of high-quality white wine. Fermentation 2020, 6, 66.

- Vaquero, C.; Loira, I.; Heras, J.M.; Carrau, F.; González, C.; Morata, A. Biocompatibility in ternary fermentations with Lachancea thermotolerans, other non-Saccharomyces and Saccharomyces cerevisiae to control pH and improve the sensory profile of wines from warm areas. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 656262.

- Vicente, J.; Calderón, F.; Santos, A.; Marquina, D.; Benito, S. High potential of Pichia kluyveri and other Pichia species in wine technology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1196.

- Mylona, A.E.; Del Fresno, J.M.; Palomero, F.; Loira, I.; Bañuelos, M.A.; Morata, A.; Calderón, F.; Benito, S.; Suárez-Lepe, J.A. Use of Schizosaccharomyces strains for wine fermentation⁻Effect on the wine composition and food safety. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016, 232, 63–72.

- Benito, S.; Palomero, F.; Calderón, F.; Palmero, D.; Suárez-Lepe, J.A. Selection of appropriate Schizosaccharomyces strains for winemaking. Food Microbiol. 2014, 42, 218–224.

- Vejarano, R. Non-Saccharomyces in winemaking: Source of mannoproteins, nitrogen, enzymes, and antimicrobial compounds. Fermentation 2020, 6, 76.

- Slaghenaufi, D.; Boscaini, A.; Prandi, A.; Cin, A.D.; Zandonà, V.; Luzzini, G.; Ugliano, M. Influence of different modalities of grape withering on volatile compounds of young and aged Corvina wines. Molecules 2020, 25, 2141.

- Mecca, D.; Benito, S.; Beisert, B.; Brezina, S.; Fritsch, S.; Semmler, H.; Rauhut, D. Influence of nutrient supplementation on Torulaspora delbrueckii wine fermentation aroma. Fermentation 2020, 6, 35.

- Guth, H. Quantitation and sensory studies of character impact odorants of different white wine varieties. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1997, 45, 3027–3032.

- Moreira, N.; Mendes, F.; Pereira, O.; Guedes De Pinho, P.; Hogg, T.; Vasconcelos, I. Volatile sulphur compounds in wines related to yeast metabolism and nitrogen composition of grape musts. Anal. Chim. Acta 2002, 458, 157–167.

- Harbertson, J.F.; Mireles, M.S.; Harwood, E.D.; Weller, K.M.; Ross, C.F. Chemical and sensory effects of saignée, water addition, and extended maceration on high brix must. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2009, 60, 450–460.

- Lleixà, J.; Manzano, M.; Mas, A.; Portillo, M.C. Saccharomyces and non-Saccharomyces competition during microvinification under different sugar and nitrogen conditions. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1959.