Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ) is a serious adverse reaction of antiresorptive and antiangiogenic agents, and it is also a potentially painful and debilitating condition.

- ONJ

- osteonecrosis

- treatment

- therapy

- surgery

- staging

1. Introduction

Whilst different treatments (therapeutic or palliative) have been described for MRONJ management, it is still a matter of controversy in the oral and maxillofacial communities that a gold standard has not yet been defined. In brief, this standard would involve the three main categories of MRONJ: (a) non-invasive procedures (ranging from pharmacological to laser treatment) [8[1][2],9], (b) invasive techniques (i.e., conservative or aggressive surgical approaches) [10][3] and (c) a combination of (a) and (b) (i.e., surgery plus one of the aforementioned non-invasive procedures) [11][4]. Non-invasive procedures include: medical treatment, intraoral vacuum-assisted treatment [12][5], the use of pentoxifylline (associated or not with tocopherol [13,14][6][7]), Er:YAG laser ablation, and Nd: YAG/diode laser biostimulation [15,16,17][8][9][10] and teriparatide [18,19,20,21][11][12][13][14]. Only partial and delayed healing has been reported with non-invasive techniques, to the exclusion of low-level laser treatment (LLLT) and, in certain cases, teriparatide. Furthermore, there is a paucity of high-impact studies in the literature, which would demonstrate effective positive outcomes [22][15].

Surgical treatments comprise: (i) conservative approaches, such as bone debridement, and sequestrectomy, and (ii) invasive, more aggressive procedures, such as re-sectioning the affected bone and jawbone reconstruction, where indicated. Several studies have yielded very positive results for surgical treatment in MRONJ treatment, especially if performed in the early stages of the disease [23,24,25,26][16][17][18][19].

Many in the field consider that the term ‘treatment’ is often used inappropriately, in that it is not possible for the disease to heal completely or for the majority of MRONJ patients to arrive at a state of remission. Thus, and as documented in the MRONJ literature, treatment goals are mainly concerned with managing pain, controlling for any infection of the soft and hard tissues and reducing the progression or occurrence of bone necrosis [11][4]. Over and above every consideration, the authors of this paper hold that maximizing a patient’s quality of life has to be a key feature of every protocol requiring MRONJ treatment.

2. Materials and Methods

In order to be included in the systematic review outlined in this paper, studies had to include results from: prospective, non-randomized and randomized clinical trials, retrospective cohort studies and case series ( n ≥ 10), which investigated the role of surgical (conservative or aggressive) techniques with or without combined procedures (surgery plus a non-invasive one) and with a follow-up ≥ 6 months. Studies were excluded if they constituted a Commentary, Review, Editorial or Protocol. Case series ( n < 10) or case reports were excluded from the pooled analysis, and the studies were limited to research regarding human beings.

Furthermore, other data sources (from international meetings and indexed dentistry journals such as Journal of Dentistry, Journal of Oral Maxillofacial Surgery, Journal of Dental Research) were scanned as a source of grey literature.

Screening and eligibility were assessed independently by two reviewers (F.C. and O.D.F.), who were in agreement regarding the results. The Titles of papers and Abstracts were initially screened for relevance and possible eligible results, and thereafter full texts were retrieved. Finally, the reviewers combined their results to create a corpus of selected papers to assess for final eligibility. According to the aim of this review, the resulting papers were allocated to four experimental categories: (1) conservative surgery, (2) aggressive surgery, (3) a conservative plus non-invasive procedure and (4) aggressive surgery plus non-invasive protocols. Table 1 and Table 2 summarize the eligible studies.

Table 1. Summary of the characteristics and the results of the studies concerning MRONJ surgical therapies.

| Treatment | Study | Study Type | Pts | Intervention | Outcome | Follow-Up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative Surgery | De Souza Povoa et al., 2016 | Case report | N = 1 Onc Stage 1 |

Removal of the exposed necrotic bone and primary wound closure | Complete healing and new bone formation in the surgical site | 26 months |

| Ribeiro et al., 2015 | Case report | N = 1 Ost Stage unspecified |

Surgical removal of whole necrotic bone, extraction of all compromised teeth | Complete healing | 12 months | |

| De Souza Faloni et al., 2011 | Case report | N = 1 Ost Stage 2 |

Conservative debridement of the necrotic bone and of part of the surrounding healthy bone, as a margin of safety | Complete healing | 8 months | |

| Pechalova et al., 2011 | Case series | N = 3 Onc Stage unspecified |

Conservative surgical debridement | Complete healing | Average of 4 months | |

| Martins et al., 2012 | Retrospective clinical study | N = 5 Onc Stage 1,2 |

Sequestrectomy and/or ostectomy and/or osteoplasty until bone marrow bleeding | 60% patients completely healed | 6 months | |

| Jung et al., 2017 | Case series | N = 7 Ost Stage 2,3 |

Patient underwent conventional surgery, and the bone defects were filled with absorbable collagen plugs. | Complete healing and new bone formation in the surgical site | 3 months | |

| Atalay et al., 2011 | Retrospective clinical study | N = 10 Onc Stage |

The affected bony tissues were curetted from the surface of the bone using bone curettes and round tungsten carbide burs. The necrotic bone was completely removed until the vital bone tissues and vessel spots appeared | 40% patients completely healed | 6 months | |

| Vescovi et al., 2012 | Retrospective clinical study | N = 17 Onc + Ost Stage 1,2,3 |

Conservative surgical treatments consisted of sequestrectomy of necrotic bone, superficial debridement/curettage, or corticotomy/surgical removal of alveolar and/or cortical bone | 53% patients completely healed | 9 months | |

| Vescovi et al., 2011 | Prospective clinical study | N = 17 Onc + Ost Stage 1,2,3 |

Conservative surgical treatments included sequestrectomies, superficial debridement/curettage and corticotomies/surgical removal of surrounding alveolar and/or cortical bone | 65% patients completely healed | 12 months | |

| Freiberger et al., 20125 | Randomized control trial | N = 19 Onc + Ost Stage 1,2,3 |

Surgical debridement of the necrotic bone | 33% patients completely healed | 24 months | |

| Fortuna et al., 2012 | Single-center prospective open-label clinical trial | N = 26 Onc Stage 2,3 |

Systemic and topical antibiotic therapy following by sequestrectomy | 73% patients completely healed | Average of 10 months | |

| Lee et al., 2014 | Case series | N = 30 Ost + Onc Stage 1,2,3 |

Minor surgical debridement was performed after irrigation, in which the necrotic bone fragments were removed | Complete healing | Average of 16 months | |

| Schubert et al., 2012 | Prospective study | N = 54 Onc + Ost Stage 1,2,3 |

Complete electrical or manual removal of the osteonecrosis until points of bleeding from the bone can be macroscopically detected. | 88.8% patients completely healed | 6 months (72%) | |

| Graziani et al., 2012 | Retrospective cohort multicenter study | N = 227 Ost + Onc Stage 1,2,3 |

Local debridement was comprised of all surgical interventions, such as sequestrectomy, soft tissue debridement and curettage, that did not require bone surgery beyond the regular margins | 49% patients completely healed |

6 months | |

| Conservative Surgery with Buccal Fat Pad Closure | Duarte et al., 2015 | Case report | N = 1 Onc Stage 2 |

The extensive necrotic bone area was surgically removed, resulting in oral sinus communication. A buccal fat pad was used to cover the defect | Complete healing | 3 months |

| Gallego et al., 2012 | Case series | N = 3 Onc + Ost Stage 1,2,3 |

Sequestrectomy and bone debridement. The overlying mucosa was sutured over the defect with reconstruction with buccal fat pad. | Complete healing | Average of 12 months | |

| Berrone et al., 2015 | Case series | N = 5 Onc Stage 3 |

Removal of the necrotic bone and primary closure of the oroantral communication using a buccal fat pad flap. | Complete healing | Average of 12 months | |

| Lopes et al., 2015 | Retrospective observational cohort study | N = 46 Onc + Ost Stage 2,3 |

Removal of all necrotic bone until bleeding was obtaining at the bony margins, conscious smoothing of all sharp bone edges and primary closure of the wound. | 87% patients completely healed |

10 months | |

| Hayashida et al., 2017 | Multicenter retrospective study | N = 38 Onc + Ost Stage 1,2,3 |

One group received conservative surgery, removal of only the necrotic bone and extensive surgery, defined as removal of the necrotic and surrounding bone (marginal mandibulectomy or partial maxillectomy). | 76.7% patients completely healed |

Average of 15 months | |

| Aggressive Surgery | Hewson et al., 2012 | Case report | N = 1 Onc Stage 3 |

Radical surgical excision of all diseased bone and nasio-labial flap reconstruction. | Complete healing | 6 months |

| Ghazali et al., 2013 | Case report | N = 1 Ost Stage 3 |

Hemimandibulectomy and an osteocutaneous fibula flap reconstruction | Complete healing | 24 months | |

| Shintani et al., 2015 | Cohort study | N = 4 Ost + Onc Stage 1,2,3 |

Segmental resection and immediate reconstruction with a reconstruction plate were performed. | 3/4 patients completely healed |

12 months | |

| Lee et al., 2014 | Case report | N = 10 Ost + Onc Stage 1,2,3 |

Large necrotic bone segment was removed by an ultrasonic bone saw. A bone file or rongeur was used for rounding the sharp bone edge. Then, the bone defect was closed by sutures or COE pack. | Complete healing | Average of 8 months | |

| Hanasono et al., 2013 | Case series | N = 13 Onc Stage2, 3 |

Segmental mandibulectomy and microvascular free flap reconstruction. | Complete healing | Average of 15 months | |

| Graziani et al., 2012 | Retrospective cohort multicenter study | N = 120 Ost + Onc Stage 1,2,3 |

Re-sective procedures were defined as corticotomy, surgical removal of the lesion and extended bone removal without prejudice for the continuity of the mandible/maxilla. | 68% patients completely healed |

6 months | |

| Hayashida et al., 2017 | Multicenter retrospective study | N = 121 Onc + Ost Stage 1,2,3 |

Extensive surgery, defined as removal of the necrotic and surrounding bone (marginal mandibulectomy or partial maxillectomy). | 86.8% patients completely healed |

Average of 15 months |

Table 2. Summary of the characteristics and the results of the studies on MRONJ surgery plus non-invasive procedures.

| Study | Study Type | Population | Intervention | Outcome | Follow-Up | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative surgery plus (+) non-invasive procedures | ||||||

| 1. Surgery + Blood Component | Gönen et al., 2017 | Case report | N = 1 Onc Stage 3 |

Sequestrectomy + PRF | Complete resolution | 18 months |

| Soydan et al., 2014 | Case report | N = 1 Onc Stage unspecified |

Curettage + PRF | Complete resolution | 6 months | |

| Maluf et al., 2016 | Case series | N = 2 Onc Stage 2 |

Resection of the necrotic tissues, curettage and osteotomy + L-PRF | Partial healing | 6 months | |

| Dincă et al., 2014 | Retrospective clinical study | N = 10 Onc Stage 2 |

Sequestrectomy or curettage + PRF | Complete resolution | 1 month | |

| Nørholt et al., 2016 | Prospective study | N = 15 Onc + Ost Stage 2,3 |

Curettage + L-PRF | 93.3% patients completely healed | 20 months | |

| Anitua et al., 2013 | Case report | N = 1 Onc Stage unspecified |

Curettage + PRGF | Complete resolution | 12 months | |

| Bocanegra-Pérez et al., 2012 | Prospective descriptive study | N = 8 Onc + Ost Stage 2 |

Curettage + PRP | Complete resolution | 14 months | |

| Mozzati et al., 2012 | Retrospective clinical study | N = 32 Onc Stage 2 |

Conservative surgery + PRFG | Complete resolution | From 48 to 50 months | |

| Tsai et al., 2016 | Case report | N = 1 Ost Stage 3 |

Surgical debridement, sequestrectomy + PRF | Complete resolution | 10 months | |

| Pelaz et al., 2014 | Cohort study | N = 5 Ost Stage 3 |

Sequestrectomy and curettage + PRF | Complete resolution | An average of 20 months | |

| Park et al., 2017 | Prospective study | N = 25 Onc + Ost Stage 1,2,3 |

Conservative surgery + L-PRF | 36% patients completely healed | 4 months | |

| Fernando de Almeida Barros Mourao C et al., 2020 | Case series | N = 11 Ost Stage 2 |

Surgical removal of necrotic bone + PRF membranes | Complete healing | 24 months | |

| Giudice A et al., 2020 | Case report | N = 1 Ost Stage 3 |

Surgical removal of necrotic bone + PRF membranes | Complete healing | 60 months | |

| Bouland C et al., 2020 | Case report | N = 2 Ost + Onc Stage 2 and 3 |

Surgical removal of necrotic bone + SVF and L-PRF membranes | Complete healing | 18 months | |

| 2. Surgery + Blood Component + Photodynamic Therapy | De Castro et al., 2016 | Case series | N = 2 Ost Stage 2,3 |

Surgical debridement + PDT + PRF | Complete resolution | An average of 12 months |

| 3. Surgery + Blood Component + Bone Morphogenetic Protein |

Park et al., 2017 | Prospective study | N = 30 Onc + Ost Stage 1,2,3 |

Conservative surgery + combined L-PRF and recombinant human BMP-2 (rhBMP-2) | 60% patients completely healed | 4 months |

| 4. Surgery + Teriparatide | Lee et al., 2010 | Case report | N = 1 Ost Stage 2 |

Sequestrectomy + teriparatide | Complete resolution | 6 months |

| 5. Surgery + Teriparatide + Bone Morphogenetic Protein | Jung et al., 2017 | Cohort study | N = 6 Ost Stage 2,3 |

Conservative surgery and absorbable collagen plugs soaked by rhBMP-2 into the bone defect plus daily subcutaneous injection of 20 mg teriparatide for 1–4 months. | Complete resolution | 3 months |

| 6. Surgery + Bone Morphogenetic Protein | Jung et al., 2017 | Cohort study | N = 4 Ost Stage 2,3 |

Conservative surgery and absorbable collagen plugs soaked by rhBMP-2 into the bone defect. | Complete resolution | 3 months |

| 7. Surgery + Blood Component + Autolugus Bone Marrow Stem Cells | Gonzálvez-García et al., 2013 | Case report | N = 1 Onc Stage 2 |

Removal of the necrotic bone+ bone marrow stem cells + beta tricalcium phosphate + demineralized bone matrix + PRP | Complete resolution | 6 months |

| De Santis et al., 2020 | Case report | N = 2 Onc Stage 2 |

Debridement of the exposed necrotic bone followed by bone marrow stem cells injection | Complete healing and new bone formation in the surgical site. | 13 months | |

| 8. Surgery + LLLT | Da Guarda et al., 2012 | Case report | N = 1 Onc Stage unspecified |

GaAlAs diode laser every 48 h for 10 days + antibiotic therapy + curettage | Complete resolution | 6 months |

| 9. Surgery + Blood Component + Laser Phototherapy | Altay et al., 2014 |

Retrospective clinical study | N = 11 Onc Stage2,3 |

Pre- and post-operative antibiotic administrations + GaA-lAs diode laser | Complete resolution | 12 months |

| Atalay et al., 2011 |

Retrospective clinical study | N = 10 Onc Stage 1,2 |

Conservative surgery + low-level laser therapy application (Er:YAG and Nd:YAG) | 70% patients completely healed | 12 months | |

| Vescovi et al., 2012 | Retrospective clinical study | N = 45 Onc + Ost Stage 1,2,3 |

Conservative surgery + laser Nd:YAG | 89% patients completely healed | 6 months | |

| Vescovi et al., 2011 |

Prospective clinical study | N = 62 Onc + Ost Stage 1,2,3 |

Conservative surgery + laser LLLT | 73% patients completely healed | 17 months. | |

| Martins et al., 2012 |

Retrospective clinical study | N = 14 Onc Stage 1,2,3 |

Conservative surgery + continuous indium-gallium-aluminum-phosphide diode laser. The LPT treatment started on the first visit and continued daily until mucosal healing was observed. | 86% patients completely healed | 12 months | |

| 10. Surgery + Ozone | Agrillo et al., 2012 |

Retrospective study | N = 94 Onc + Ost Stage unspecified |

Curettage or sequestrectomy + Ozone therapy (3 min sessions 2/week) + pharmacological therapy | 90% patients completely healed | An average of 6 months |

| 11. HBO + Surgery * | Fatema et al., 2013 |

Case report | N = 1 Onc Stage 2 |

Antibiotics therapy, irrigation, pre-operative HBO therapy for 20 sessions, conservative minor surgical debridement and again post-operative HBO therapy for ten sessions. | Complete resolution | Unspecified |

| Al-Zoman et al., 2013 |

Case series | N = 3 Onc Stage2,3 |

HBO therapy, oral/parenteral antibiotic, analgesics, conservative surgery (debridement of bone sequestra) and daily rinsing with chlorhexidine mouthwash. | Complete resolution | 12 months | |

| Freiberger et al., 2012 | Randomized control trial | N = 24 Onc + Ost Stage 1,2,3 |

40 HBO treatments at 2.0 atm for 2 h twice per day and conservative surgical debridement of the necrotic bone. | 52% patients completely healed | 24 months | |

| 12. Ozone + Surgery* | Ripamonti et al., 2012 | Case report | N = 1 Onc Stage unspecified |

Antibiotic + antimycotic therapy for 10 days. Local ozone gas (total of 15 applications). Conservative surgery (sequestrectomy). | Complete resolution | 36 months |

| Brozoski et al., 2020 | Case series | N = 2 Onc + Ost Stage 2 |

Weekly irrigation with aqueous ozone solution on bone-exposed region + daily mouthwashes of ozone solution. After 3 and 6 months: conservative surgery (debridement and sequestrectomy) | Complete resolution | An average of 24 months | |

| 13. Teriparatide + Surgery * | Doh et al., 2015 | Case report | N = 1 Ost Stage 2 |

After 4 months of daily teriparatide therapy conservative surgery (sequestrectomy). The TPTD therapy was terminated 6 months after the initial treatment. | Complete resolution | 20 months |

| Kwon et al., 2012 | Case series | N = 6 Ost Stage 2,3 |

Daily Teriparatide (20 μg/day) 1–3 months + conservative sequestrectomy/marginal/aggressive segmental resection | Complete resolution | 3 months | |

| Kakehashi et al., 2015 | Case series | N = 10 Ost Stage 2,3 |

Daily teriparatide (20 μg/day) ranged from 4 to 24 months. In some cases, surgery was performed to obtain the healing. | Partial resolution | From 4 to 24 months (duration of teriparatide therapy until mucosal healing) | |

| Aggressive surgery plus non-invasive procedures | ||||||

| 1. Surgery + Bone Graft + Bone Morphogenetic Protein | Rahim I 2015 |

Case report | N = 1 Ost Stage 3 |

Partial mandibulectomy + bone graft from the iliac crest + rhBMP-7 | Complete resolution | 60 months |

| 2. AF-Guided Surgery + LLLT | Vescovi P 2015 |

Case report | N = 1 Onc Stage 3 |

Osteotomy with Er:YAG laser + AF visualization to guide the osteoplasty. Intraoral irrigations with povidone iodine solution + application of Nd:YAG laser + weekly applications of LLLT for 3 weeks after intervention | Complete resolution | 7 months |

Data collection was independently performed by two authors (F.C. and A.G.), and their results were reviewed by a third author (O.D.F.) to check for accuracy.

3. Results

Aggressive surgery plus non-invasive procedures (auxiliary treatment): only two papers (case reports) discussed the results of aggressive surgery protocols with auxiliary treatment [49,60][20][21].

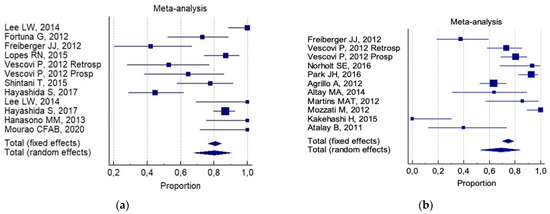

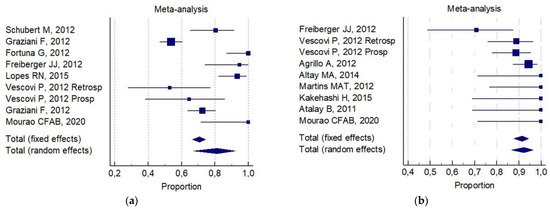

The overall 6-month total resolution rate (a) and the 6-month improvement rate (b) were: 74% (CI 95%; 64–83%) and 87% (CI 95%; 78–94%), respectively. The following was reported for (a): 80% (CI 95%; 68–90%) for invasive surgery alone ( Figure 2 a). 69% (95% CI; 53–84%) for invasive surgery plus non-invasive procedures ( Figure 2 b).

The following was reported for (b): 81% (CI 95%; 67–92%) for invasive surgery alone ( Figure 3 a). 92% (CI 95%; 88–94%) for invasive surgery plus non-invasive procedures ( Figure 3 b).

Of interest, a significant statistical difference was observed in the 6-month improvement rate, on comparing combined conservative surgery (mean = 91%) versus only surgical (conservative alone and aggressive alone) techniques (mean 77%, p = 0.05). There was no significant difference for any group with respect to the 6-month total resolution rate (82% versus 72%, respectively). No reliable data were available for an analysis of aggressive surgery plus a non-invasive procedure with respect to all the selected indicators.

4. Discussion

Referring to the systematic review described herein, the associations between conservative surgery plus blood components, and laser or photodynamic therapy, appear to contribute much to: newly formed bone, the full coverage of bone tissue with healthy mucosa and the absence of symptoms and other signs of necrotic progression. This is due to the analgesic, anti-inflammatory and biomodulatory effects of blood components, and this protocol has been shown to be effective on average over a 6-month follow-up period with a success rate of 86%.

The association of autologous bone marrow stem cells with conservative surgery and blood components has been reported only in one case study, with a success rate of 100% on average over a 6-month follow-up period. The CT scan revealed the diminution of osteolytic lesions with complete bone regeneration of the medial cortex of the lower jaw and a total resolution of symptoms.

The use of surgery has also been associated with teriparatide (TPTD) treatment (prior to or after conventional surgical treatment) for MRONJ in osteoporotic patients. TPTD stimulates trabecular and cortical thickness, and trabecular connectivity and bone size bone formation by increasing osteoblast number and activity. Although successful results using TPTD treatment have been reported in the literature, its safety and efficacy are currently awaiting comprehensive evaluation. The treatment time during which it can be safely administered is strictly limited to less than 2 years in one lifespan [57,58,59][22][23][24]. A success rate of 83% on average over an 11-month follow-up period has been reported for the surgical treatment plus TPTD treatment (or vice versa) of MRONJ: any surgical wound completely healed with X-rays indicating stable alveolar bone. No inflammatory signs and symptoms have been reported to date.

As a pre-surgical treatment, HBO has successfully treated MRONJ lesions, thereby: improving the quality of life of afflicted patients [52,53,54][25][26][27], increasing wound healing, and reducing edema, inflammation and pain. HBO followed by surgical treatment had a success rate of 84% on average over an 18-month follow-up period, with: the complete healing of MRONJ lesion, total mucosal coverage, a cessation in the signs of infection and notable symptomatic relief.

References

- Gómez-Moreno, G.; Arribas-Fernández, M.C.; Fernández-Guerrero, M.; Castro, A.B.; Aguilar-Salvatierra, A.; Guardia, J.; Botticelli, D.; Calvo-Guirado, J.L. Bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw 2 years after teeth extractions: A case report solved with non-invasive treatment. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2014, 18, 1391–1397.

- Moretti, F.; Pelliccioni, G.A.; Montebugnoli, L.; Marchetti, C. A prospective clinical trial for assessing the efficacy of a minimally invasive protocol in patients with bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaws. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endodontology 2011, 112, 777–782.

- Bedogni, A.; Saia, G.; Bettini, G.; Tronchet, A.; Totola, A.; Bedogni, G.; Ferronato, G.; Nocini, P.F.; Blandamura, S. Long-term outcomes of surgical resection of the jaws in cancer patients with bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis. Oral Oncol. 2011, 47, 420–424.

- Beth-Tasdogan, N.H.; Mayer, B.; Hussein, H.; Zolk, O. Interventions for managing medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 10, CD012432.

- Laimer, J.; Steinmassl, O.; Hechenberger, M.; Rasse, M.; Pikula, R.; Bruckmoser, E. Intraoral Vacuum-Assisted Closure Therapy—A Pilot Study in Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 75, 2154–2161.

- Owosho, A.A.; Estilo, C.L.; Huryn, J.M.; Yom, S.K. Pentoxifylline and tocopherol in the management of cancer patients with medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: An observational retrospective study of initial case series. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2016, 122, 455–459.

- Magremanne, M.; Reychler, H. Pentoxifylline and Tocopherol in the Treatment of Yearly Zoledronic Acid–Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw in a Corticosteroid-Induced Osteoporosis. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2014, 72, 334–337.

- Porcaro, G.; Amosso, E.; Scarpella, R.; Carini, F. Doxycycline fluorescence-guided Er:YAG laser ablation combined with Nd:YAG/diode laser biostimulation for treating bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2015, 119, e6–e12.

- Luomanen, M.; Alaluusua, S. Treatment of bisphosphonate-induced osteonecrosis of the jaws with Nd:YAG laser biostimulation. Lasers Med. Sci. 2011, 27, 251–255.

- Heggendorn, F.L.; Leite, T.C.; Cunha, K.S.G.; Júnior, A.S.; Gonçalves, L.S.; Da Costa, K.B.F.F.; Dias, E.P. Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws: Report of a case using conservative protocol. Spéc. Care Dent. 2016, 36, 43–47.

- Yoshiga, D.; Yamashita, Y.; Nakamichi, I.; Tanaka, T.; Yamauchi, K.; Yamamoto, N.; Nogami, S.; Kaneuji, T.; Mitsugi, S.; Sakurai, T.; et al. Weekly teriparatide injections successfully treated advanced bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws. Osteoporos. Int. 2013, 24, 2365–2369.

- Ohbayashi, Y.; Miyake, M.; Sawai, F.; Minami, Y.; Iwasaki, A.; Matsui, Y. Adjunct teriparatide therapy with monitoring of bone turnover markers and bone scintigraphy for bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2013, 115, e31–e37.

- Yamachika, E.; Matsubara, M.; Ikeda, A.; Matsumura, T.; Moritani, N.; Iida, S. Treatment of Osteonecrosis of the Jaw. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2015, 26, e575–e577.

- Thumbigere-Math, V.; Michalowicz, B.S.; Hodges, J.S.; Tsai, M.L.; Swenson, K.K.; Rockwell, L.; Gopalakrishnan, R. Periodontal disease as a risk factor for bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. J. Periodontol. 2014, 85, 226–233.

- Mauceri, R.; Panzarella, V.; Maniscalco, L.; Bedogni, A.; Licata, M.E.; Albanese, A.; Toia, F.; Cumbo, E.M.G.; Mazzola, G.; Di Fede, O.; et al. Conservative Surgical Treatment of Bisphosphonate-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw with Er,Cr:YSGG Laser and Platelet-Rich Plasma: A Longitudinal Study. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 1–10.

- Hayashida, S.; Soutome, S.; Yanamoto, S.; Fujita, S.; Hasegawa, T.; Komori, T.; Kojima, Y.; Miyamoto, H.; Shibuya, Y.; Ueda, N.; et al. Evaluation of the Treatment Strategies for Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaws (MRONJ) and the Factors Affecting Treatment Outcome: A Multicenter Retrospective Study with Propensity Score Matching Analysis. J. Bone Min. Res. 2017, 32, 2022–2029.

- Aljohani, S.; Troeltzsch, M.; Hafner, S.; Kaeppler, G.; Mast, G.; Otto, S. Surgical treatment of medication-related osteonecrosis of the upper jaw: Case series. Oral Dis. 2019, 25, 497–507.

- Schiodt, M.; Vadhan-Raj, S.; Chambers, M.S.; Nicolatou-Galitis, O.; Politis, C.; Coropciuc, R.; Fedele, S.; Jandial, D.; Zhang, J.; Ma, H.; et al. A multicenter case registry study on medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients with advanced cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2018, 26, 1905–1915.

- Ristow, O.; Rückschloß, T.; Müller, M.; Berger, M.; Kargus, S.; Pautke, C.; Engel, M.; Hoffmann, J.; Freudlsperger, C. Is the conservative non-surgical management of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw an appropriate treatment option for early stages? A long-term single-center cohort study. J. Cranio-Maxillofacial Surg. 2019, 47, 491–499.

- Vescovi, P.; Giovannacci, I.; Otto, S.; Manfredi, M.; Merigo, E.; Fornaini, C.; Nammour, S.; Meleti, M. Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw: An Autofluorescence-Guided Surgical Approach Performed with Er:YAG Laser. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2015, 33, 437–442.

- Rahim, I.; Salt, S.; Heliotis, M. Successful long-term mandibular reconstruction and rehabilitation using non-vascularised autologous bone graft and recombinant human BMP-7 with subsequent endosseous implant in a patient with bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2015, 53, 870–874.

- Kwon, Y.-D.; Lee, D.-W.; Choi, B.-J.; Lee, J.-W.; Kim, D.-Y. Short-term teriparatide therapy as an adjunctive modality for bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws. Osteoporos. Int. 2012, 23, 2721–2725.

- Doh, R.-M.; Park, H.-J.; Rhee, Y.; Kim, H.S.; Huh, J.; Park, W. Teriparatide Therapy for Bisphosphonate-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw Associated With Dental Implants. Implant. Dent. 2015, 24, 222–226.

- Kakehashi, H.; Ando, T.; Minamizato, T.; Nakatani, Y.; Kawasaki, T.; Ikeda, H.; Kuroshima, S.; Kawakami, A.; Asahina, I. Administration of teriparatide improves the symptoms of advanced bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: Preliminary findings. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2015, 44, 1558–1564.

- Al-Zoman, K.H.; Albazie, S.; Robert, A.A.; Baskaradoss, J.K.; Alsuwyed, A.S.; Ciancio, S.; Al-Mubarak, S. Surgical management of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: Report of three cases. J. Palliat. Care 2013, 29, 52–57.

- Fatema, C.N.; Sato, J.; Yamazaki, Y.; Hata, H.; Hattori, N.; Shiga, T.; Tamaki, N.; Kitagawa, Y. FDG-PET may predict the effectiveness of hyperbaric oxygen therapy in a patient with bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: Report of a case. Odontology 2013, 103, 105–108.

- Freiberger, J.J.; Padilla-Burgos, R.; McGraw, T.; Suliman, H.B.; Kraft, K.H.; Stolp, B.W.; Moon, R.E.; Piantadosi, C.A. What Is the Role of Hyperbaric Oxygen in the Management of Bisphosphonate-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw: A Randomized Controlled Trial of Hyperbaric Oxygen as an Adjunct to Surgery and Antibiotics. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2012, 70, 1573–1583.