The aim of the article is to discuss the development of calcium channel blocker (CCB) influenced gingival enlargement.

- drug-influenced gingival enlargement

- calcium channel blockers

- adverse drug reactions

- side effect

- nifedipine

- amlodipine

Note: The entry will be online only after author check and submit it.

1. Introduction

| CALCIUM CHANNEL BLOCKERS | Amlodipine, Benidipine, Diltiazem, Felodipine, Manidipine Nitrendipine, Nicardipine, Nifedipine, Nisoldipine, Nimodipine, Verapamil |

| ANTI-EPILEPTIC DRUGS | Carbamezepine, Clobazam, Diazepam, Ethosuximide, Ethotoin, Gabapentin, Lamotrigine, Levitiracetam, Methosuxinimide, Mepenytoin, Phenytoin, Phenobarbitone, Primidone, Sodium Valproate *, Topiramate, Vigabatrin, Zonisamide |

| IMMUNOSUPPRESSIVE DRUGS | Cyclosporine, Everolimus, Mycophenolate mofetil, Sirolimus, Tacrolimus |

| MISCELLANEOUS | Erythromycin *, Ethinyl Estradiol, and Lynestrenol (oral contraceptives, in high doses), Lisinopril *, Atenolol *, Propanolol * |

2. Prevalence

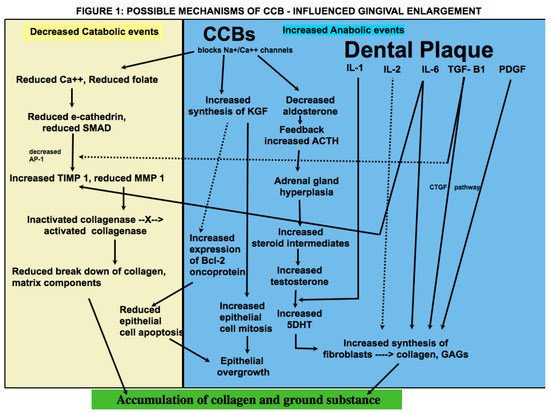

3. Pathophysiology

Effect of Dose on Pathogenesis

Conclusions

4. Conclusions

When enlargement of an organ occurs due to an increase in the number of cells, the condition is referred to as hyperplasia, whereas when enlargement occurs due to increase in the size of the cells, it is referred to as hypertrophy. What was termed as drug-induced gingival hyperplasia is now known as drug-influenced gingival enlargement, categorized under “dental biofilm induced gingivitis” in the most recent classification scheme for periodontal diseases [30]. This change in terminology reflects an evolution in understanding of the pathogenesis and development of DIGE. Whereas earlier studies focused on the theory that DIGE is caused by an increase in connective tissue elements, more recent studies suggest that it is a result of an imbalance between catabolic and anabolic mechanisms that are necessary for regulating the periodontium [9]. Historically, the pathogenesis of DIGE has been described as being caused by inflammatory and noninflammatory mechanisms; however, they are not distinct or separate; rather, the pathways appear to be confluent in various steps of the disease. In addition, there is insurmountable evidence that dental plaque is necessary for the development and progress of the condition and that the offending drug mainly alters the response of the periodontium to plaque bacteria. It is also important to remember that plaque-induced gingival inflammation does not only contribute to the occurrence of DIGE but is also a consequence of it due to limited access for oral hygiene. The literature involving pathogenesis of CCB-influenced GE, treatment and clinical outcome of various treatment modalities is conflicting. Nevertheless, the subject is of great relevance due to the widespread use of the drugs that cause it, the pervasiveness of the systemic diseases that require their use, and the functional and cosmetic implications of DIGE. Within the limitation of this article, it may be inferred that genetic makeup, plaque induced gingival inflammation, type of drug used, duration of drug use, lifestyle and oral hygiene habits, treatment modalities utilized, and patient compliance are important prognostic factors that affect the prevalence and severity of the condition, long-term clinical outcome, and risk of recurrence following periodontal treatment. More studies that focus on predisposing factors should be undertaken that will aid in identifying individuals who are at greater risk for developing DIGE. Patients taking these drugs must be forewarned about this side effect so that they take adequate oral hygiene measures that will help prevent or at least minimize the condition. Longitudinal studies on causes of recurrence will help shed light on why periodontal therapy is successful in some patients, whereas in others, there is recrudescence of gingival enlargement.

1. Bharti, V.; Bansal, C. Drug-induced gingival overgrowth: The nemesis of gingiva unravelled. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 2013, 17, 182–187. [CrossRef]

2. Hatahira, H.; Abe, J.; Hane, Y.; Matsui, T.; Sasaoka, S.; Motooka, Y.; Hasegawa, S.; Fukuda, A.; Naganuma, M.; Ohmori, T.; et al. Drug-induced gingival hy will helperplasia: A retrospective study using spontaneous reporting system databases. J. Pharm. Health Care Sci. 2017, 3, 1–11. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

3. Prachi, S.; Jitensheder, S.; Rahul, C.; Jitendra, K.; Priyanka, M.; Disha, S. Impact of oral contraceptives on periodontal health. Afr. Health Sci. 2019, 19, 1795–1800. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

4. McKeever, R.G.; Hamilton, R.J. Calcium Channel Blockers. 2019. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482473/ (accessed on 1 July 2021).

5. Bloch, M.J.; Basile, J. Major Side Effects and Safety of Calcium Channel Blockers. 2019. Available online: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/major-sideeffects-and-safety-of-calciumchannel-blockers (accessed on 1 July 2021).

6. Kimball, O.P. The treatment of epilepsy with sodium diphenyl hydantoinate. JAMA 1939, 112, 1244–1245. [CrossRef]

7. Pasupuleti, M.K.; Musalaiah, S.V.; Naligasree, M.; Kumar, P.A. Combination of inflammatory and amlodipine induced gingival overgrowth in a patient with cardiovascular disease. Avicenna J. Med. 2013, 3, 68–72. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

8. Ganesh, P.R. Immunoexpression of interleukin-6 in drug-induced gingival overgrot on wth patients. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 2016, 7, 140–145. [CrossRef]

9. Brown, R.S.; Arany, P. Mechanism of drug-induced gingival overgrowth revisited: A unifying hypothesis. Oral Dis. 2014, 21, e51–e61. [CrossRef]

10. Ramperion, Y.; Behar, S.; Kishon, Y.; Engelberg, I.S. Gingival hyperplasia caused by nifedipine—A preliminary report. Int. J. Cardiol. 1984, 5, 195–204. [CrossRef]

11. Lederman, D.; Lumerman, H.; Reuben, S.; Freedman, P.D. Gingival hyperplasia associaontal ted with nifedipine therapy. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1984, 57, 620–622. [CrossRef]

12. Seymour, R.A.; Ellerapy is, J.; Thomason, J.M.; Monkman, S.; Idle, J.R. Amlodipine-induced gingival overgrowth. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1994, 21, 281–283. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

13. Gaur, S.; Agnihotri, R. Is dental plaque the only etiologisuccal factor in Amlodipine induced gingival overgrowth? A systematic review of evidence. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2018, 10, e610–e619. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

14. Thomason, J.M.; Seymossfur, R.A.; Ellis, J.S.; Kelly, P.J.; Parry, G.; Dark, J.; Wilkinson, R.J.; Ilde, J.R. Determinants of gingival overgrowth severity in organ transplant patients. An examination of the role of HLA phenotype. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1996, 23, 628–634. [CrossRef]

15. Pernu, H.E.; Pernu, L.M.H.; Knuuttil in some pa, M.L. Effect of periodontal treatment on gingival overgrowth among Cyclosproine A treated renal transplant recipients. J. Periodontol. 1993, 64, 1098–1100. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

16. Daley, T.D.; Wysocki, G.P. Cyclosporine Therapy: Its Significance toients, the Periodontist. J. Periodontol. 1984, 55, 708–712. [CrossRef]

17. Tahamtan, S.; Shirban, F.; Bagherniya, M.; Johnston, T.P.; Sahebkar, A. The effects of statins on dental and oral health: A review of preclinical and clinical studies. J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 1–42. [CrossRef]

18. Khzam, N.; Bailey, D.; Yie, H.S.; Bakr, M.M. Gingival Enlargement Induced by Felodipine Resolves with a Conventional Periodontal Treatment and Drug Modification. Case Rep. Dent. 2016, 2016, 1–6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

19. Nyska, A.; Shemesh, M.; Tal,reas H.; Dayan, D. Gingival hyperplasia induced by calcium channel blockers: Mode of action. Med. Hypotheses 1994, 43, 115–118. [CrossRef]

20. Soo otheriyamoorthy, M.; Gower, D.B.; Eley, B.M. Androgen metabolism in gingival hyperplasia induced by nifedipine and cyclosporin. J. Periodontal. Res. 1990, 25, 25–30. [CrossRef]

21. Nishikawa, S.; Tada, H.; Hamasaki, A.; Kasahara, S.; Kido, J.-I.; Naga, ta, T.; Ishida, H.; Wakano, Y. Nifedipine-Induced Gingival Hyperplasia: A Clinical and In Vitro Study. J. Periodontol. 1991, 62, 30–35. [CrossRef]

22. Aldemere ir, N.M.; Begenik, H.; Emre, H.; Erdur, F.M.; Soyoral, Y. Amlodipine-induced gingival hyperplasia in chronic renal failure: A case report. Afr. Heal. Sci. 2013, 12, 576–578. [CrossRef]

23. S recrubramani, T.; Rathnavelu, V.; Alitheen, N.B. The Possible Potential Therapeutic Targets for Drug Induced Gingival Overgrowth. Mediat. Inflamm. 2013, 2013, 1–9. [CrossRef]

24. Kaesasa, S.; Soory, M. The effect of interleukin-1 (IL-1) on androgen metabolism in human gingival tissue (HGT) and periodontal ligament (PDL). J. Clin. Periodontol. 1996, 23, 419–424. [CrossRef]

25. Ramírez-Rámiz, A.; Brunet-Llobet, L.; Lahor-Soler, E.; Miranda-Rius, J. Oen the Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Drug-Induced Ge of gingival Overgrowth. Open Dent. J. 2017, 11, 420–435. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

26. Seymour, R.A.; Elenlis, J.S.; Thomason, J.M. Risk factors for induced gingival over growth. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2000, 27, 217–223. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

27. Thorgemason, J.M.; Ellis, J.S.; Jovanovski, V.; Corson, M.; Lynch, E.; Seymour, R.A. Analysis of changes in gingival contour from three-dimensional co-ordinate data insubjects with drug-induced gingival overgrowth. Jnt. Clin. Periodontol. 2005, 32, 1069–1075. [CrossRef] Oral 2021, 1 249

28. Tejnani, A.; Gandevivala, A.; Bhanushali, D.; Gourkhede, S. Combined treatment for a combined enlargement. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 2014, 18, 516–519. [CrossRef]

29. Ikawa, K.; Ikawa, M.; Shimauchi, H.; Iwakura, M.; Sakamot, S. Treatment of gingival overgrowth induced by Manidipine administration. A case report. J. Periodontol. 2002, 73, 115–122. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

30. Caton, J.G.; Armitage, G.; Berglundh, T.; Chapple, I.L.; Jepsen, S.; Kornman, K.S.; Mealey, B.L.; Papapanou, P.N.; Sanz, M.;Tonetti, M.S. A new classification scheme for periodontal and peri-implant diseases and conditions-Introduction and key changes from the 1999 classification. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2018, 45, S1–S8. [CrossRef]

References

- Caton, J.G.; Armitage, G.; Berglundh, T.; Chapple, I.L.; Jepsen, S.; Kornman, K.S.; Mealey, B.L.; Papapanou, P.N.; Sanz, M.; Tonetti, M.S. A new classification scheme for periodontal and peri-implant diseases and conditions-Introduction and key changes from the 1999 classification. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2018, 45, S1–S8.

- Brown, R.S.; Arany, P. Mechanism of drug-induced gingival overgrowth revisited: A unifying hypothesis. Oral Dis. 2014, 21, e51–e61.

- Prachi, S.; Jitender, S.; Rahul, C.; Jitendra, K.; Priyanka, M.; Disha, S. Impact of oral contraceptives on periodontal health. Afr. Health Sci. 2019, 19, 1795–1800.

- McKeever, R.G.; Hamilton, R.J. Calcium Channel Blockers. 2019. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482473/ (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Bloch, M.J.; Basile, J. Major Side Effects and Safety of Calcium Channel Blockers. 2019. Available online: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/major-sideeffects-and-safety-of-calciumchannel-blockers (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Kimball, O.P. The treatment of epilepsy with sodium diphenyl hydantoinate. JAMA 1939, 112, 1244–1245.

- Pasupuleti, M.K.; Musalaiah, S.V.; Nagasree, M.; Kumar, P.A. Combination of inflammatory and amlodipine induced gingival overgrowth in a patient with cardiovascular disease. Avicenna J. Med. 2013, 3, 68–72.

- Ganesh, P.R. Immunoexpression of interleukin-6 in drug-induced gingival overgrowth patients. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 2016, 7, 140–145.

- Brown, R.S.; Arany, P. Mechanism of drug-induced gingival overgrowth revisited: A unifying hypothesis. Oral Dis. 2014, 21, e51–e61.

- Ramon, Y.; Behar, S.; Kishon, Y.; Engelberg, I.S. Gingival hyperplasia caused by nifedipine—A preliminary report. Int. J. Cardiol. 1984, 5, 195–204.

- Lederman, D.; Lumerman, H.; Reuben, S.; Freedman, P.D. Gingival hyperplasia associated with nifedipine therapy. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1984, 57, 620–622.

- Seymour, R.A.; Ellis, J.; Thomason, J.M.; Monkman, S.; Idle, J.R. Amlodipine-induced gingival overgrowth. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1994, 21, 281–283.

- Gaur, S.; Agnihotri, R. Is dental plaque the only etiological factor in Amlodipine induced gingival overgrowth? A systematic review of evidence. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2018, 10, e610–e619.

- Thomason, J.M.; Seymour, R.A.; Ellis, J.S.; Kelly, P.J.; Parry, G.; Dark, J.; Wilkinson, R.J.; Ilde, J.R. Determinants of gingival overgrowth severity in organ transplant patients. An examination of the role of HLA phenotype. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1996, 23, 628–634.

- Pernu, H.E.; Pernu, L.M.H.; Knuuttila, M.L. Effect of periodontal treatment on gingival overgrowth among Cyclosproine A treated renal transplant recipients. J. Periodontol. 1993, 64, 1098–1100.

- Daley, T.D.; Wysocki, G.P. Cyclosporine Therapy: Its Significance to the Periodontist. J. Periodontol. 1984, 55, 708–712.

- Tahamtan, S.; Shirban, F.; Bagherniya, M.; Johnston, T.P.; Sahebkar, A. The effects of statins on dental and oral health: A review of preclinical and clinical studies. J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 1–42.

- Khzam, N.; Bailey, D.; Yie, H.S.; Bakr, M.M. Gingival Enlargement Induced by Felodipine Resolves with a Conventional Periodontal Treatment and Drug Modification. Case Rep. Dent. 2016, 2016, 1–6.

- Nyska, A.; Shemesh, M.; Tal, H.; Dayan, D. Gingival hyperplasia induced by calcium channel blockers: Mode of action. Med. Hypotheses 1994, 43, 115–118.

- Sooriyamoorthy, M.; Gower, D.B.; Eley, B.M. Androgen metabolism in gingival hyperplasia induced by nifedipine and cyclosporin. J. Periodontal. Res. 1990, 25, 25–30.

- Nishikawa, S.; Tada, H.; Hamasaki, A.; Kasahara, S.; Kido, J.-I.; Nagata, T.; Ishida, H.; Wakano, Y. Nifedipine-Induced Gingival Hyperplasia: A Clinical and In Vitro Study. J. Periodontol. 1991, 62, 30–35.

- Aldemir, N.M.; Begenik, H.; Emre, H.; Erdur, F.M.; Soyoral, Y. Amlodipine-induced gingival hyperplasia in chronic renal failure: A case report. Afr. Heal. Sci. 2013, 12, 576–578.

- Subramani, T.; Rathnavelu, V.; Alitheen, N.B. The Possible Potential Therapeutic Targets for Drug Induced Gingival Overgrowth. Mediat. Inflamm. 2013, 2013, 1–9.

- Kasasa, S.; Soory, M. The effect of interleukin-1 (IL-1) on androgen metabolism in human gingival tissue (HGT) and periodontal ligament (PDL). J. Clin. Periodontol. 1996, 23, 419–424.

- Ramírez-Rámiz, A.; Brunet-Llobet, L.; Lahor-Soler, E.; Miranda-Rius, J. On the Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Drug-Induced Gingival Overgrowth. Open Dent. J. 2017, 11, 420–435.

- Seymour, R.A.; Ellis, J.S.; Thomason, J.M. Risk factors for induced gingival over growth. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2000, 27, 217–223.

- Thomason, J.M.; Ellis, J.S.; Jovanovski, V.; Corson, M.; Lynch, E.; Seymour, R.A. Analysis of changes in gingival contour from three-dimensional co-ordinate data insubjects with drug-induced gingival overgrowth. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2005, 32, 1069–1075.

- Tejnani, A.; Gandevivala, A.; Bhanushali, D.; Gourkhede, S. Combined treatment for a combined enlargement. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 2014, 18, 516–519.

- Ikawa, K.; Ikawa, M.; Shimauchi, H.; Iwakura, M.; Sakamot, S. Treatment of gingival overgrowth induced by Manidipine administration. A case report. J. Periodontol. 2002, 73, 115–122.