The fast growth of Entrepreneurship Education (EE) in universities reflects the underlying assumption that EE fosters increased levels of entrepreneurship . Nowadays, EE is related to much more than economic activities and business creation. Policymakers support EE for unlocking personal potential and its contribution to developing key competencies for lifelong learning. European Union defined entrepreneurship competence as “the capacity to act upon opportunities and ideas and to transform them into values for others”. The most important barriers to youth business creation and self-employment are the lack of knowledge and skills for entrepreneurship and the fear of failure, which highlights the importance of building entrepreneurship competencies and confidence for youth in a multidisciplinary environment and “embedding entrepreneurship teaching at all levels of education”.

- student’s entrepreneurship

- entrepreneurship education

1. Introduction

Universities are well situated for building youth’s entrepreneurial competencies. Fostering entrepreneurial awareness and incorporating entrepreneurial mindsets into students’ attitudes through EE are increasingly recognized as part of a university’s role [1][2][3].

Universities are encouraging students to consider entrepreneurship as a potential career path mainly by the provision of theoretically oriented courses which teach ‘about’ entrepreneurial traits, awareness, the impact of courses or impact of different cultures on entrepreneurship [4] and provide training in conventional management-related subjects such as business plans, marketing, financial management or small business management [5].

Of all outcomes of EE, EI is considered the best single predictor of entrepreneurship behavior [4][6][7][8]. This assumption is embedded in a large body of research in the field focusing on EI (51%, according to Nabi et al. [9]). In most empirical research, EI is simply defined as “the intention to start a new business” [7] at some point in the future that might be imminent, indeterminate, although it may never be reached [10]. Another popular approach considers EI as the intention to become self-employed [11].

In our analysis, we draw on Souitaris et al. [12] to define the benefits for students of EE: learning, program-derived entrepreneurial inspiration, and incubation resources. Learning covers the entrepreneurship knowledge acquired by students during the EE program. Inspiration is seen as a change of heart and mind, or a change of emotion and motivation provoked by the EE program and oriented towards considering becoming an entrepreneur [12]. Finally, the incubator resources cover advice from faculty members and from a pool of entrepreneurial-minded classmates from building a team. We also emphasize that the benefits of EE are being built in an entrepreneurship program, which includes a portfolio of activities complementing the traditional teaching.

2. Empirical Approaches to Estimations of Entrepreneurial Intentions

A large body of empirical estimations of EI has been guided by two models: Shapero and Sokol’s Model of Entrepreneurial Event [13] and Azjen’s Theory of Planned Behavior [14].

A large body of empirical estimations of EI has been guided by two models: Shapero and Sokol’s Model of Entrepreneurial Event [31] and Azjen’s Theory of Planned Behavior [32].Shapero and Sokol’s Model of Entrepreneurial Event (SEE) considers that EI is predicting actual entrepreneurship behavior. As factors that control an individual’s EI, SEE is focusing on perceived desirability, feasibility, and propensity to act. In the context of EI, perceived desirability refers to how attracting is the entrepreneurship endeavor for a person. Perceived feasibility quantifies the degree to which one feels capable of starting a business [15], and perceived propensity to act reflects the volitional aspects of intention [11].

Shapero and Sokol’s Model of Entrepreneurial Event (SEE) considers that EI is predicting actual entrepreneurship behavior. As factors that control an individual’s EI, SEE is focusing on perceived desirability, feasibility, and propensity to act. In the context of EI, perceived desirability refers to how attracting is the entrepreneurship endeavor for a person. Perceived feasibility quantifies the degree to which one feels capable of starting a business [33], and perceived propensity to act reflects the volitional aspects of intention [29].Starting from SEE and due to the integration of major social psychology theories: the social cognitive theory (SCT) [16][17] and the theory of planned behavior (TPB) [14][18], empirical analyses of the EI are increasingly common, most of them have developed their own models. Integrated and mixed versions of SEE, SCT, and TPB have served as major theoretical grounds for these models.

Starting from SEE and due to the integration of major social psychology theories: the social cognitive theory (SCT) [34,35] and the theory of planned behavior (TPB) [32,36], empirical analyses of the EI are increasingly common, most of them have developed their own models. Integrated and mixed versions of SEE, SCT, and TPB have served as major theoretical grounds for these models.Although it was not developed specifically for EI, it has become popular in modeling EI after its empirical validation [19]. In the context of EI, TPB states that intentions are determined by attitudes toward entrepreneurship, subjective norms (or perceived social pressure to engage or not in entrepreneurship), and perceived behavioral control.

Although it was not developed specifically for EI, it has become popular in modeling EI after its empirical validation [37]. In the context of EI, TPB states that intentions are determined by attitudes toward entrepreneurship, subjective norms (or perceived social pressure to engage or not in entrepreneurship), and perceived behavioral control.Obviously, TPB and SEE models have overlapping mechanisms of EI formation. In an effort to integrate both theories, Krueger et al. [15] argue that subjective norms overlap with desirability and feasibility and that feasibility overlaps with perceived behavioral control. In their turn, Iakovleva and Kolvereid [11] show that perceived desirability and feasibility, integrated into one construct, mediate the influence of attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control on EI.

Obviously, TPB and SEE models have overlapping mechanisms of EI formation. In an effort to integrate both theories, Krueger et al. [33] argue that subjective norms overlap with desirability and feasibility and that feasibility overlaps with perceived behavioral control. In their turn, Iakovleva and Kolvereid [29] show that perceived desirability and feasibility, integrated into one construct, mediate the influence of attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control on EI.In sum, the TPB models have been developed to improve the estimation of intentions and, when applied to estimating the EI, they successfully explain from 40% to 60% in the variation of the EI construct, which represent a significant improvement over the initial estimations of EI which were only controlling for personal traits [11].

In sum, the TPB models have been developed to improve the estimation of intentions and, when applied to estimating the EI, they successfully explain from 40% to 60% in the variation of the EI construct, which represent a significant improvement over the initial estimations of EI which were only controlling for personal traits [29].Nevertheless, improvements to the general framework of the TBP and SEE model have been proposed in EI empirical research. Efforts have been made in search of an individual characteristic specific to entrepreneurship. Consequently, the Entrepreneurial Self Efficacy (ESE) concept was introduced for the study of EI [19][20]. ESE refers to the belief in an individual’s ability to succeed in entrepreneurial endeavors [21]. The same research points out that ESE is a task-specific construct, addressing the lack of specificity problem, specific to previous research which controls for personality traits in EI estimations. Moreover, empirical research in the field documents the statistically significant relationship between ESE and EI, with studies even considering ESE as closest to actual entrepreneurship behavior [20]. In this respective, ESE acts upon the EI and entrepreneurial emotions. From here, the benefits of ESE lead to actual entrepreneurial behavior, venture creation, and entrepreneurial performance [22].

Nevertheless, improvements to the general framework of the TBP and SEE model have been proposed in EI empirical research. Efforts have been made in search of an individual characteristic specific to entrepreneurship. Consequently, the Entrepreneurial Self Efficacy (ESE) concept was introduced for the study of EI [37,38]. ESE refers to the belief in an individual’s ability to succeed in entrepreneurial endeavors [39]. The same research points out that ESE is a task-specific construct, addressing the lack of specificity problem, specific to previous research which controls for personality traits in EI estimations. Moreover, empirical research in the field documents the statistically significant relationship between ESE and EI, with studies even considering ESE as closest to actual entrepreneurship behavior [38]. In this respective, ESE acts upon the EI and entrepreneurial emotions. From here, the benefits of ESE lead to actual entrepreneurial behavior, venture creation, and entrepreneurial performance [40].3. Transmission Mechanisms of the Benefits of Entrepreneurship Education to Entrepreneurial Intentions

We can draw on Human Capital Theory (HCT) to understand the mechanism that enables EE to enhance entrepreneurship. Building on the THC, many studies [23][24][25] have argued that human capital attributes are the main determinants of entrepreneurial success. Of course, human capital encompasses not only knowledge and skills related to formal or non-formal EE but also aspects related to previous work experience and role models [26][27][28][29][30][31].

We can draw on Human Capital Theory (HCT) to understand the mechanism that enables EE to enhance entrepreneurship. Building on the THC, many studies [41,42,43] have argued that human capital attributes are the main determinants of entrepreneurial success. Of course, human capital encompasses not only knowledge and skills related to formal or non-formal EE but also aspects related to previous work experience and role models [44,45,46,47,48,49].Also, the socio-cognitive models have been a suitable approach to analyze the mechanism of the benefits of EE to EI. ESE is essential in the context of measuring the EI as an output of EE, providing an important theoretical perspective linking the two concepts. According to Bandura’s SCT [16][17], there are four processes influencing self-efficacy development: mastery experiences, role modeling and vicarious experience, social persuasion, and judgments of one’s own physiological states. Zhao et al. [6] analyze the specific configuration of ESE as an antecedent of EI. They argue that the pedagogical practices specific to entrepreneurship courses impact, without exception, all these processes: “enactive mastery (simulated business exercises, best business case competition, the provision of venture capital to entrepreneurship students), role modeling and vicarious experience (successful local entrepreneurs invited to lecture, case studies of prestigious entrepreneurs presented, project work with an entrepreneur, etc.), social persuasion (students’ projects evaluation, students’ career mentoring, etc.), judgments of one’s physiological states (helping students to develop their psychological coping strategies through examples of the lifestyles and working styles of successful entrepreneurs, etc.).”

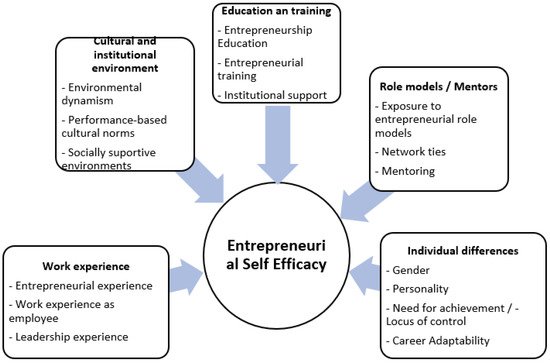

Also, the socio-cognitive models have been a suitable approach to analyze the mechanism of the benefits of EE to EI. ESE is essential in the context of measuring the EI as an output of EE, providing an important theoretical perspective linking the two concepts. According to Bandura’s SCT [34,35], there are four processes influencing self-efficacy development: mastery experiences, role modeling and vicarious experience, social persuasion, and judgments of one’s own physiological states. Zhao et al. [25] analyze the specific configuration of ESE as an antecedent of EI. They argue that the pedagogical practices specific to entrepreneurship courses impact, without exception, all these processes: “enactive mastery (simulated business exercises, best business case competition, the provision of venture capital to entrepreneurship students), role modeling and vicarious experience (successful local entrepreneurs invited to lecture, case studies of prestigious entrepreneurs presented, project work with an entrepreneur, etc.), social persuasion (students’ projects evaluation, students’ career mentoring, etc.), judgments of one’s physiological states (helping students to develop their psychological coping strategies through examples of the lifestyles and working styles of successful entrepreneurs, etc.).” AsFigure 1

shows, firm characteristics and cultural and institutional environment also contribute to the development of the ESE construct.

Figure 1. The antecedents of Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy. Source: Adapted from Newman et al., 2019 [22].

HCT and SCT provide thereby the two theoretical perspective linking EE to EI and further on to entrepreneurship behavior. Accordingly, the TPB models have been used to analyses the influence of EE on students’ EI [8].

HCT and SCT provide thereby the two theoretical perspective linking EE to EI and further on to entrepreneurship behavior. Accordingly, the TPB models have been used to analyses the influence of EE on students’ EI [27].4. Cross Campus Entrepreneurship Education Approach

Numerous empirical studies that explore the efficiency of entrepreneurial university supply worldwide, including Romania [32][33][34][35][36][37], show that the EI is significantly positively related to the entrepreneurial orientation of the university [28]. It is widely recognized that business orientation is a significant determinant of students’ attitude toward entrepreneurship [32][38][39], and entrepreneurial education should be extended outside the business school [40], especially at engineering programs [33][41].

EE expansion beyond economics faculties and business schools has given entrepreneurship education increased flexibility and greater applications [42]. Cross-campus EE [42][43][44] or radiant university-wide model in EE [45][46] is focusing on the specific context of non-Economics students with entrepreneurship courses outside the Faculty of Economics. A cross-campus approach to EE is considered “extremely appealing to students” [46] because it allows the formation of entrepreneurial competencies within the faculty and customized on the specialization followed, but it has two major disadvantages: high cost and administrative difficulties.

If these obstacles are overcome, the cross-campus EE approach opens the perspective of a broad rethinking of entrepreneurship education in universities outside the Economics faculties and Business schools [47][48]. The advantages of this model of entrepreneurship education are much greater from the perspective of customizing entrepreneurial education in the students’ field of study. This model simulates the students’ EI in their field of study and allows EE to connect with self-employment and employability.

As Decker-Lange [49] recently showed, “employability and entrepreneurship skills overlap”, this is the reason why cross-campus EE is helpful in nurturing not only entrepreneurship and self-employment but also employability.

5. Entrepreneurship Education and Its Contribution to Inclusive Entrepreneurship

The origin and practice of inclusive entrepreneurship are linked to a project having the same name led by Syracuse University in partnership with the Burton Blatt Institute. The program has fostered a better understanding of the entrepreneurial ecosystem and the skills needed for successful entrepreneurs, providing participants with opportunities to channel their creativity, develop the skills and the drives for entrepreneurial pursuits [50].

The concept of inclusive entrepreneurship was quickly adopted by policymakers throughout the world. OECD approaches inclusive entrepreneurship from a mixed perspective: business creation for disadvantaged or under-represented groups in entrepreneurship and self-employment for people at risk [51] (pp. 18–19). Inclusive entrepreneurship has also been addressed within the European Union’s strategy for more and better jobs through the Community for Practice on Inclusive Entrepreneurship (COPIE) project led to developing specific tools for under-represented groups in entrepreneurship.

In recent years, youth have been a typical target group for inclusive entrepreneurship policy in European Union and OECD countries. European Commission has included entrepreneurship competence as a key competence that all individuals need for personal fulfillment and social inclusion [52]. Consequently, EE also serves the objective of inclusiveness through its contribution to increasing the human capital of students. Among the best practices in Romanian higher education, we mention that already Romanian universities are using EE as a tool for increasing the attractiveness of its educational content, contributing to alleviating the school dropout phenomenon, which, in Romania, is considered a social risk [53][54][55][56].

Within the framework of inclusive entrepreneurship, extensive research is focusing on gender differences in entrepreneurship. Research has documented the existence of a gender gap in entrepreneurship, with women being less successful entrepreneurs than men [57][58][59]. Some studies directly associate entrepreneurial intention with masculine traits [60][61][62].