Brain injuries are devastating conditions, representing a global cause of mortality and morbidity, with no effective treatment to date. Increased evidence supports the role of neuroinflammation in driving several forms of brain injuries. High mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) protein is a pro-inflammatory-like cytokine with an initiator role in neuroinflammation that has been implicated in Traumatic brain injury (TBI) as well as in early brain injury (EBI) after subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). Herein, we discuss the implication of HMGB1-induced neuroinflammatory responses in these brain injuries, mediated through binding to the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE), toll-like receptor4 (TLR4) and other inflammatory mediators. Moreover, we provide evidence on the biomarker potential of HMGB1 and the significance of its nucleocytoplasmic translocation during brain injuries along with the promising neuroprotective effects observed upon HMGB1 inhibition/neutralization in TBI and EBI induced by SAH. Overall, this review addresses the current advances on neuroinflammation driven by HMGB1 in brain injuries indicating a future treatment opportunity that may overcome current therapeutic gaps.

- high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1)

- traumatic brain injury (TBI)

- subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH)

- neuroinflammation

- biomarker

1. Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a devastating disorder associated with a major cause of morbidity and mortality leading to significant direct and indirect costs to society. TBI refers to a complex disorder associated with several degrees of contusion, diffuse axonal injury (DAI), hemorrhage, and hypoxia [1]. These effects cumulatively initiate biochemical and metabolic changes causing gradual tissue damage and cell death [2]. Although several agents have shown promising neuroprotective effects against TBI in pre-clinical settings, they failed to improve outcome in clinical trials [3][4]. These poor effects may be attributed to the disparate nature of TBI, with differences in clinical variables such as tissue biomechanics site and severity of injury [5][6].

Despite the extensive advances in clinical and pre-clinical research, the pathomechanism underlying TBI are still elusive. However, there is evidence on the contribution of neuroinflammation and blood–brain barrier (BBB) disruption in driving the secondary damage after brain injury [7]. Improved neurological effects have been reported in experimental TBI upon inhibition of post-traumatic neuroinflammatory response [8][9].

Targeting neuroinflammation to inhibit the secondary damage post-TBI represents an effective strategy in recent days. One of the inflammatory mediators that seem to be implicated in brain injury is the high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) protein, a pro-inflammatory-like cytokine released actively after activation of other cytokines and passively during cell death [10]. HMGB1 released from stressed and dying brain cells acts as an effective neuroinflammatory mediator [11]. HMGB1 is mainly expressed in all cell types, including neurons and glial cells. Overexpression of extracellular HMGB1 was observed in several neuroinflammatory conditions, including TBI [12], Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) [13], Epilepsy [14], Alzheimer’s diseases (AD) [15], Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) [16][17] Parkinson’s diseases (PD) [18], etc.

Furthermore, HMGB1-mediated neuroinflammatory response has been implicated in several types of brain injury including TBI [19] and early brain injury (EBI) after SAH [13] as well as in cerebral ischemia-induced and hypoxic ischemic (HI)-induced brain injuries [20].

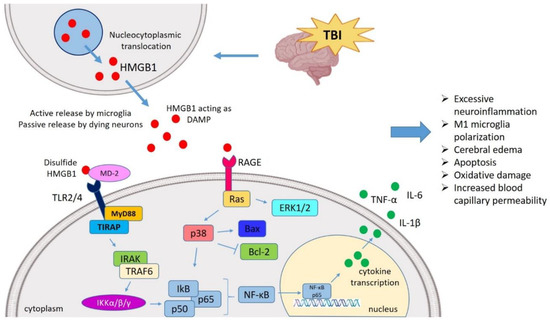

HMGB1 was demonstrated to drive the neuroinflammatory response after TBI leading to secondary damage as evident by its up-regulated expression and release after experimental TBI induction (Figure 1) [21][22]. Similarly, HMGB1-mediated neuroinflammatory response contributes to early brain injury (EBI) after SAH [13]. Active HMGB1 translocation from nuclei to the extracellular space after TBI and SAH was shown to activate neuroinflammatory cascades and rupture the BBB. Of interest, HMGB1-targeted therapies such as an anti-HMGB1 monoclonal antibody (mAb) and the pharmacological inhibitor Glycyrrhizin were effective experimentally in inhibiting the neuroinflammatory response post-TBI and in minimizing the EBI after SAH. This reflects that HMGB1 might be a promising extracellular target against these conditions leading to new treatment opportunities.

Figure 1. HMGB1 mediated neuroinflammatory response in TBI. TBI induces nucleocytoplasmic translocation of HMGB1 resulting into the release of HMGB1 in extracellular milieu. The extracellular HMGB1 may be partially oxidized at the two cysteine residues generating the disulfide form of HMGB1. The disulfide HMGB1 further binds to its prominent receptor system such as TLR4 and RAGE which in turn interacts with MD-2 and initiates the MyD88 dependent pathway. It also binds to Ras to initiate the ERK pathway, respectively. HMGB1-TLR4 axis can activate NF-κB signaling both directly and through TRAF6. These pathways ultimately interact with the NF-κB lead to the generation of neuroinflammatory response by producing several pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6). In this way, HMGB1 might mediate the TBI-induced secondary injury where HMGB1 is understood to amplify vicious neuroinflammation, M1 polarization, apoptosis, oxidative damage, cerebral edema, increased BBB permeability. TBI, Traumatic brain injury; HMGB1, High mobility group box 1; TLR4, Toll-like receptor 4; MD-2, Myeloid differentiation factor-2; MyD88, Myeloid differentiation response protein 88; ERK, Extracellular signal-related kinase; NF-κB, Nuclear factor κ light chain enhancer of activated B cells; TNF-α, Tumor necrosis factor-α; IL, Interleukin; BBB, Blood–brain barrier; TRAF6, TNF receptor-associated factor 6.

Herein, we address the role of HMGB1-mediated neuroinflammatory response as a mechanism of secondary injury after TBI and HMGB1-mediated neuroinflammation in EBI after SAH. Moreover, we discuss the emerging preclinical findings of HMGB1-targeting studies demonstrating inhibition of both TBI-induced secondary damage and EBI after SAH.

2. Insights into the HMGB1 Biology

HMGB1 is a 25-kDa DNA-binding protein composed of 215 amino acids, consisting of two DNA bindings sites (Box A and Box B) and a negatively charged C-terminal [23][24]. HMGB1 can be secreted extracellularly through active and passive release that occurs in both somatic and immune cells [25]. After reaching to the extracellular milieu, HMGB1 serves as a damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) protein and exerts a compelling inflammatory response, engaging several inflammatory mediators. Upon release from neurons and astrocytes, HMGB1 begins the production of several inflammatory markers, including TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β [26]. Extracellular HMGB1 interacts with several pathogen recognition receptors (PRRs), namely the toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) and the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE), to initiate cell migration and production of cytokines [27]. The ability of HMGB1 to interact with several receptors depends on the post-translational redox modifications (PTMs) of the three cysteine residues (at positions 23, 45, and 106 in the box A and B domains of HMGB1) [28].

Moreover, three isoforms of HMGB1 have been identified: the fully reduced HMGB1, the disulfide HMGB1, and the sulphonyl HMGB1. The fully reduced isoform of HMGB1 binds to CXCL12, which further interacts with a great affinity to CXCR4. The extracellular TLR4 adaptor myeloid differentiation factor-2 (MD-2) forms a complex only with the disulfide isoform of HMGB1 (not to any other redox forms) and aggravates the expression of chemokines and cytokines [29] at a comparable level to lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced production of pro-inflammatory cytokines [30]. Disulfide HMGB1 signaling through TLR4 enhances the activation of nuclear factor-κ light chain enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) and consequently the transcription of pro-inflammatory cytokines [31]. Due to its cytokine-inducing potential, HMGB1 has gained increased attention in recent days and was extensively studied in several inflammatory diseases [23].

3. HMGB1 Targeted Therapies against Brain Injuries

In recent days, HMGB1 has emerged as an extracellular target against a diverse range of CNS disorders with HMGB1 involvement, including AD [15], PD [18], MS [32], Epilepsy [33], TBI [12], SAH [13], etc. Moreover, HMGB1 targeted therapy conferred neuroprotective effects against these diseases mainly by inhibiting its expression and release, blocking its translocation, and down-regulating the expression of inflammatory molecules. Common HMGB1 targeting strategies in experimental studies include the use of anti-HMGB1 mAb and the natural HMGB1 inhibitors Glycyrrhizin with its derivatives, and Ethyl pyruvate [34][35] which have recently gained increasing attention as potential therapeutic strategies against several diseases of CNS and of the peripheral nervous system (PNS) [36][37]. In the following sections, the promising outcomes of HMGB1 inhibition by the anti-HMGB1 mAb and Glycyrrhizin in TBI and SAH are discussed.

3.1. HMGB1 Neutralization against TBI

In FPI-induced TBI, treatment with anti-HMGB1 mAb was shown to significantly suppress the HMGB1 translocation in neurons and retain its immunoreactivity in the nuclei. The anti-HMGB1 mAb attenuated neuronal cell death as evidenced by the intact nissl-positive pyramidal neurons and protected BBB integrity based on the significant inhibition of Evans blue leakage (by 88%), impeding the leakage area to the primary lesion area. Moreover, treatment with anti-HMGB1 mAb improved motor functions as evident from the rotarod and cylinder test and suppressed the activation of inflammatory molecules (TNF-α, iNOS, HIF-1α, COX-2, VEGF-A189, and VEGF-A165) [12].

The anti-HMGB1 mAb treatment in the FPI-induced TBI model also suppressed microglia as evident by reduced CD68-positive cells, ameliorated neuronal cell death in the hippocampus based on low TUNEL positivity, inhibited HMGB1 translocation and reduced plasma HMGB1 levels. Moreover, anti-HMGB1 mAb exerted beneficial effects on the impairment of motor and cognitive functions that were present for 14 days post-TBI [38].

Similarly, in a model of intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH)-induced brain injury, the anti-HMGB1 mAb inhibited its translocation into the extracellular space, decreased its serum levels and reduced brain edema while it maintained the permeability of BBB. Moreover, the anti-HMGB1 mAb reduced microglial activation, reduced oxidative stress, ameliorated behavioral performance and down-regulated the expression of inflammation-related mediators (TNF-α, iNOS, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8R, COX-2, MMP2, MMP9 and VEGF 121) [39]. All these promising findings indicate that anti-HMGB1 mAb therapy might be beneficial against TBI.

The natural small molecule Glycyrrhizin binds directly to both HMG boxes, inhibiting its chemoattractant and mitogenic properties [34] and exerting protective effects against experimental TBI. Glycyrrhizin treatment ameliorated TBI-induced brain edema and beam walking distance, inhibited the translocation of HMGB1 and down-regulated TBI-induced up-regulation of HMGB1, RAGE, TLR4, and NF-κB. It further inhibited cell apoptosis and reduced TBI-induced up-regulation of inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6) [40]. Glycyrrhizin conferred neuroprotection in a preclinical model of pediatric TBI by decreasing brain HMGB1 levels, edema, and preventing impairment of spatial and motor learning [21]. Thus, targeting HMGB1 by Glycyrrhizin might reduce the inflammatory cascades and ameliorate the motor function after TBI.

Please note that binding of Glycyrrhizin to HMGB1 is concentration-dependent with an equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd) value of 4.03 µM. Glycyrrhizin blocks HMGB1 binding to its receptor RAGE and inhibits TBI. In turn it inhibits the TBI-induced HMGB1 translocation and suppresses the reduction of HMGB1 from the site of injury. It further inhibits the BBB permeability and down-regulates the expression of inflammatory molecules (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6) [41]. It is worth noting that Glycyrrhizin has a wide therapeutic window, as shown by the fact that it is effective even at 6 h post-TBI [41].

It further affects microglial polarization, exerting a neuroprotective effect. In a preclinical model, Glycyrrhizin treatment inhibited HMGB1 expression and release after TBI as evident by the presence of scarce HMGB1 in several nuclei which was completely lost in the injured area of TBI rats. Moreover, it inhibited M1 phenotype and induce M2 phenotype activation of microglia/macrophages (5 days post-TBI) as evident by the reduction in CD86, iNOS, TNF-α, and IL-1β (M1 phenotype markers and functional cytokine mRNA levels) and up-regulation in the markers and the functional cytokine mRNA levels of the M2 phenotype (CD206, Arg1, Ym1, and IL-10) [42].

Ethyl pyruvate is an aliphatic ester developed from an endogenous metabolite [43] that can counteract HMGB1 and neutralize it, further exhibiting biological effects in several diseases [44][45][46]. Its therapeutic potential against experimental TBI relies mainly on HMGB1 inhibition. In a modified Feeney’s weight drop model of TBI, treatment with ethyl pyruvate was shown to inhibit TBI-induced up-regulation of HMGB1 and TLR4 expression. Moreover, it inhibited NF-κB DNA-binding activity, reduced expression of inflammatory molecules (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6) and ameliorated locomotor function as evident by beam walking performance, along with cerebral edema and cortical apoptotic cell death [47].

Immunohistochemical findings and western blot analysis from the TBI model in rodents revealed that Ethyl pyruvate treatment reduced HMGB1, TLR4 and RAGE expression after TBI in the pericontusional cerebral tissue. Moreover, the treatment protected BBB permeability as evidenced by increased Occludin, Claudin-5, and ZO-1 levels of BBB tight junction binding proteins, increased total antioxidant status, decreased total oxidant status and oxidative stress index [48].

Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid (ω-3 PUFA) possess a neuroprotective effect which is attributed to the modulation of inflammatory pathways [49]. Supplements of ω-3 PUFA have exerted beneficial effects against clinical [50] and experimental model of TBI [51]. Recently, ω-3 PUFA were shown to exert neuroprotective effects against experimental TBI mainly through the modulation of HMGB1 pathway. In an experimental Feeney DM TBI model, ω-3 PUFA supplementation inhibited TBI-induced activation of microglia by fostering a change from the M1 to the M2 phenotype and decreased the inflammatory response (as evident by down-regulation of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IFN-γ). It also reduced neuronal apoptosis post-TBI and enabled neuronal recovery mainly by inhibiting HMGB1 release and translocation as well as HMGB1-mediated stimulation of the TLR4/NF-κB signaling axis [52][51].

Altogether these studies indicate that HMGB1 inhibition by the anti-HMGB1 mAb, Glycyrrhizin, Ethyl pyruvate and ω-3 PUFA exhibit promising effects in experimental TBI mainly by inhibiting the secondary damage. However, the safety profile of these HMGB1-targeted therapies needs to be further explored since mAb treatment has been associated with immunotoxicity and difficult penetration of BBB [53], thus limiting its translational implication. The studies of HMGB1 targeting therapies in TBI are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Studies targeting HMGB1 in TBI.

| S.N. | Study Model | Intervention and Dosing Schedule | Observations | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | FPI-induced TBI in adult male Wistar rats | Anti-HMGB1 mAb (1 mg/kg, I.V.) was administered at 5 min and 6 h after TBI |

|

[38] |

| 2 | ICH-induced brain injury in male Wistar rats | Anti-HMGB1 mAb (1 mg/kg, I.V.) was administered immediately and 6 h after ICH. |

|

[39] |

| 3 | FPI-induced TBI in adult male Wistar rats | Anti-HMGB1 mAb (1 mg/kg, I.V.) was administered at 5 min and 6 h after TBI |

|

[12] |

| 4 | CCI-induced TBI in male C57Bl/6 mice | GL (for acute recovery study) (50 mg/kg, I.P.) was administered 1 h, 6 h, 1 d and 2 d post-injury, plus 1 h pre-injury. GL (for chronic recovery study) was administered 1 h pre-injury, at 1 h, 6 h post-injury, plus once daily for 7 added days for 1 week. |

|

[21] |

| 5 | TBI induced by modified Feeney’s free weight drop method in male SD rats | GL (10 mg/kg, I.V.) administered 30 min after TBI |

|

[40] |

| 6 | FPI-induced TBI in adult male Wistar rats | GL (0.25, 1.0 or 4.0 mg/kg, I.V.) was administered 5 min after injury |

|

[41] |

| 7 | ICH-induced injury in male SD rats | GL (50 mg/kg) was administered 20 min post-ICH, and then once daily for 3 days. |

|

[54] |

| 8 | DAI-induced brain injury in adult SD rats | Glycyrrhizic acid (GA) (10 mg/kg, I.V.) administered 30 min before DAI |

| |

| Feeney DM TBI model in adult male SD rats | ||||

| ω-3 PUFA (2 mL/kg, I.P.) was administered 30 min after TBI, each day for 1 week. | ||||

|

[52] | |||

| 13 | Feeney DM TBI model in adult male SD rats | ω-3 PUFA (2 mL/kg, I.P.) was administered 30 min post-TBI, each day for 1 week. |

|

[51] |

TBI, Traumatic brain injury, HMGB1, High mobility group box-1; ω-3 PUFA, Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid; FPI, Fluid percussion injury, Anti-HMGB1 mAb, Anti-HMGB1 monoclonal antibody; SD, Sprague-Dawley; TNF-α, Tumor necrosis factor-alpha; NF-κB, Nuclear factor κ-light chain enhancer of activated B cells; IL, Interleukin; IFN-γ, Interferon-gamma; I.P., Intraperitoneal; I.V., Intravenous; BBB, Blood–brain barrier; VEGF, Vascular endothelial growth factor, HIF-1α, Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 α; COX-2, Cyclooxygenase-2; iNOS, Inducible nitric oxide synthase; CCI, Controlled cortical impact; ICH, Intracerebral hemorrhage; DAI, Diffuse axonal injury; MMP, Matrix metalloproteinase; EP, Ethyl Pyruvate; GL, Glycyrrhizin; SIRT, Sirtuin; MWM, Morris water maze.

3.2. HMGB1-Targeted Therapy Attenuates EBI Post-SAH

Of importance, EBI after SAH leads to neuroinflammation, brain edema, increased permeability of BBB, apoptosis, and neuronal degeneration [57]. This indicates that attenuating EBI induced by SAH might ameliorate neurological damage and improve the outcome. Also, several pre-clinical findings have reported that inhibition of neuroinflammation exerted significant protection against EBI after SAH [58][59]. Hence, therapeutic inhibition of post-SAH inflammatory cascades might prevent EBI.

Exploring and developing therapeutic agents that reduce EBI and delay cerebral vasospasm (CVS) post-SAH have emerged as effective therapeutic strategies. The anti-HMGB1 mAb attenuated the progression of delayed cerebral vasospasm (CVS) mainly by inhibiting HMGB1 translocation in the VSMCs and reducing SAH up-regulated plasma HMGB1 levels. Also, it suppressed the up-regulation of vasoconstriction-mediating molecules (PAR1, TXA2, AT1, ETA). Moreover, the anti-HMGB1 mAb treatment reduced SAH-induced up-regulation of inflammatory molecules (TLR4, IL-6, TNF-α, and iNOS) and ameliorated the neurological symptoms [13], indicating that anti-HMGB1 mAb interrupts the CVS and brain injury after SAH.

In a preclinical model, Glycyrrhizin was shown to suppress the inflammatory response post-SAH mainly by inhibiting the expression of HMGB1. Other mechanisms underlying Glycyrrhizin treatment include reduction of SAH-induced neuronal apoptosis, reduction of inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α and IL-1β), inhibition of BBB permeability post-SAH and reduction of SAH-induced neuronal degeneration [60]. These findings indicate that Glycyrrhizin protects the brain injury of SAH and may present a potential therapy against HMGB1-induced brain inflammation and injury.

In a double-hemorrhage model of SAH, Glycyrrhizic acid ameliorated neurological outcome, inhibited CVS as evident by the increased diameter of BA, and reduced the thickness of the vascular wall. It reduced HMGB1 expression in the BA, and down-regulated the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α) [61], further suggesting that Glycyrrhizic acid exerted neuroprotection on CVS post-SAH, mainly through inhibition of HMGB1 expression and release, and reduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines.

Several other molecules also demonstrated beneficial effects in experimental SAH, including Resveratrol, Purpurogallin, Melatonin, Rhinacanthin-C, and AG490 (inhibitor of JAK/STAT3). These agents mainly inhibit HMGB1 expression and release, as well as its nuclear to cytosolic translocation, further ameliorating neural apoptosis, brain edema and down-regulating SAH-induced inflammatory markers (TLR4, MyD88, and NF-κB, TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β) [62][63][64][65][66] (Table 2). It is, therefore, suggested that HMGB1-targeted therapy might regulate a complex series of inflammatory responses contributing to EBI post-SAH, mainly through suppression of the TLR4/NF-κB signaling cascade.

Table 2. Summaries of studies targeting HMGB1 against EBI induced by SAH.

| S.N. | Study Model | Intervention and Dosing Schedule | Observations | References | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Endovascular puncture model of SAH adult male Wistar rats | Anti-HMGB1 mAb (1 mg/kg, I.V.) was administered post-SAH, twice at an interval of 24 h. |

|

[13] | ||||

| 2 | Endovascular perforation model of SAH adult male SD rats | Anti-HMGB1 mAb (1 mg/kg, I.V.) was administered post-SAH, twice at an interval of 24 h. |

|

[67] | ||||

| 3 | Prechiasmatic cistern SAH model in male SD rats | Glycyrrhizin (GL) (15 mg/kg, I.P.) was administered immediately and then 6, 12 and 18 h post-SAH. |

|

[60] | ||||

| 4 | SAH in male SD rats | GL (5 mg/kg/day) was administered 24 h prior (precondition) and 1 h post-SAH (treatment). |

|

[68] | ||||

| 5 | Modified double-hemorrhage SAH model in male SD rats | Glycyrrhizic acid (GA) (10 mg/kg, I.P.) was administered immediately after SAH and was continued for three consecutive days. |

|

[61] | ||||

| 6 | Endovascular perforation induced SAH in male SD rats | AG490 (inhibitor of JAK2/STAT3) (2 mL, I.V.) was administered 30 min before SAH |

|

[62] | ||||

| 7 | Prechiasmatic cistern SAH model in male SD rats | Resveratrol (60 mg/kg, I.P.) was administered at 2 and 12 h post-SAH. |

|

[59] | ||||

| [ | 55 | ] | ||||||

| 8 | Double-hemorrhage SAH model in male SD rats | Purpurogallin (100, 200 and 600 mg/kg/day) was administered 1 h after SAH. |

|

[64] | 9 | Weight-dropping TBI model in male adult SD rats | Ethyl pyruvate (EP) (75 mg/kg, I.P.) prepared at 30 min, 1.5 h, and 6 h |

|

| 9 | Prechiasmatic cistern SAH model in SD rats |

|

Melatonin (150 mg/kg, I.P.) was administered 2 and 24 h after SAH. |

| [48] | |||

| [ | 66 | ] | 10 | Feeney’s weight drop model in male SD rats | EP (75 mg/kg, I.P.) administered 5 min, 1 h, and 6 h post-TBI |

|

[47] | |

| 10 | Rodents SAH model in male SD rats | Rhinacanthin-C (RCT-C) (100, 200, and 400 µmol/kg/day) was administered orally 1 h after SAH and every 12 h. |

|

[65] | 11 | CCI-induced TBI in male SD rats | Minocycline (90 mg/kg, I.P.) was administered 10 min and 20 h after injury |

|

| 11 | Double-hemorrhage SAH model in male SD rats | 4OGOMV (100, 200 and 400 µg/kg/day) was administered 1 h post-SAH. |

| [56] | ||||

| [ | 69 | ] | 12 |

SAH, Subarachnoid hemorrhage; HMGB1, high mobility group box-1; TLR4, Toll-like receptor-4; Anti-HMGB1 mAb, Anti-HMGB1 monoclonal antibody; SD, Sprague-Dawley; VSMC, vascular smooth muscle cell; I.P., Intraperitoneal; I.V., Intravenous; BBB, Blood–brain barrier; iNOS, Inducible nitric oxide synthase; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; TNF-α, Tumor necrosis factor-alpha; IL, Interleukin; NF-κB, Nuclear factor κ-light chain enhancer of activated B cells; MyD88, Myeloid differentiation factor 88; TXA2, Thromboxane A2; PAR1, Protease-activated receptor-1; AT1, Angiotensin II type 1; ETA, Endothelin type A; PPAR, Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ; GL, Glycyrrhizin; GA, Glycyrrhizic acid; MWM, Morris water maze; 4OGOMV, 4′-O-β-D-glucosyl-5-O-methylvisamminol; MDI, Motor deficit index; MCP-1, Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; JAK2, Janus kinase 2; STAT3, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3.

4. Discussion and Future Suggestions

Current research directions in TBI are mainly focused on preventing the secondary damage and on inhibiting the neuroinflammation that contributes to both acute and chronic stages. HMGB1 has been suggested to participate in the progression of TBI and might represent a promising target. During TBI, cellular damage/death might cause HMGB1 to translocate from the nucleus to extracellular space resulting in microglial activation and leading to further release of HMGB1 [39]. Elucidation of HMGB1 translocation and release process along with HMGB1-driven activation of the TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway post-TBI may prove beneficial in understanding the mechanism of TBI-induced secondary brain damage [51].

HMGB1-based agents (anti-HMGB1 mAb and Glycyrrhizin) have been shown to exert neuroprotective effects in experimental TBI models including amelioration of neurological outcome, inhibition of translocation of HMGB1, down-regulation of TBI-induced neuroinflammatory responses, prevention of BBB breakdown and reduction of microglial activation [12][41]. Similarly, HMGB1 neutralization inhibited SAH-induced EBI mainly by protecting BBB permeability, blocking HMGB1 expression, release, and translocation, and down-regulating SAH-induced neuroinflammatory response. These findings suggest that HMGB1 might represent an extracellular target against several forms of brain injury such as TBI and EBI induced by SAH. Nevertheless, when evaluating the beneficial therapeutic effect of HMGB1, it will be important to assess its effect on long-term cognitive function. The prolonged absence of HMGB1 might impair the cognitive function despite its beneficial effects on preventing secondary injury [70]. Moreover, assessment of the duration of beneficial effects upon HMGB1 neutralization/inhibition must be determined [12][38].

Despite the compelling findings from experimental studies, no clinical data reporting beneficial effects of HMGB1-targeted therapies against TBI and SAH-induced EBI are available. Moreover, extensive investigation of HMGB1 targeting agents against brain injuries is warranted since the degree, the location, and the duration of HMGB1 neutralization might be complex and variable due to different insult etiologies [70]. HMGB1 has therefore emerged as an attractive therapeutic target against several HMGB1-mediated inflammatory diseases [23][71]. A future challenge for the clinical translation of HMGB1-based therapies is the development of isoform-specific HMGB1 inhibitors that could suppress the damage without inhibiting tissue regeneration because the thiol-HMGB1 isoform may possess a tissue protecting role in inflammation, injury, and regeneration. All currently available HMGB1 antagonists bind to all the three redox forms of HMGB1 [23] and therefore future studies should be focused on blocking the harmful disulfide-HMGB1 isoform that exerts inflammatory role [23][25].

5. Conclusions

Altogether HMGB1 protein is a key mediator of neuroinflammatory response and contributes to the pathogenesis of TBI as well as to the secondary damage post-TBI and in the EBI following SAH. Moreover, HMGB1 can be used as a biomarker to predict functional outcome after TBI and EBI after SAH while its therapeutic neutralization may prove beneficial in inhibiting the secondary damage following these injuries.

References

- Saatman, K.E.; Duhaime, A.-C.; Bullock, R.; Maas, A.I.; Valadka, A.; Manley, G.T. Classification of traumatic brain injury for targeted therapies. J. Neurotrauma 2008, 25, 719–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Saatman, K.E.; Duhaime, A.-C.; Bullock, R.; Maas, A.I.; Valadka, A.; Manley, G.T. Classification of traumatic brain injury for targeted therapies. J. Neurotrauma 2008, 25, 719–738.

- McIntosh, T.K.; Smith, D.H.; Meaney, D.F.; Kotapka, M.J.; Gennarelli, T.A.; Graham, D.I. Neuropathological sequelae of traumatic brain injury: Relationship to neurochemical and biomechanical mechanisms. Lab. Investig. A J. Tech. Methods Pathol. 1996, 74, 315–342. [Google Scholar]McIntosh, T.K.; Smith, D.H.; Meaney, D.F.; Kotapka, M.J.; Gennarelli, T.A.; Graham, D.I. Neuropathological sequelae of traumatic brain injury: Relationship to neurochemical and biomechanical mechanisms. Lab. Investig. A J. Tech. Methods Pathol. 1996, 74, 315–342.

- Bragge, P.; Synnot, A.; Maas, A.I.; Menon, D.K.; Cooper, D.J.; Rosenfeld, J.V.; Gruen, R.L. A state-of-the-science overview of randomized controlled trials evaluating acute management of moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 2016, 33, 1461–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Bragge, P.; Synnot, A.; Maas, A.I.; Menon, D.K.; Cooper, D.J.; Rosenfeld, J.V.; Gruen, R.L. A state-of-the-science overview of randomized controlled trials evaluating acute management of moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 2016, 33, 1461–1478.

- Hawryluk, G.W.; Bullock, M.R. Past, present, and future of traumatic brain injury research. Neurosurg. Clin. 2016, 27, 375–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Hawryluk, G.W.; Bullock, M.R. Past, present, and future of traumatic brain injury research. Neurosurg. Clin. 2016, 27, 375–396.

- McKee, A.C.; Daneshvar, D.H. The neuropathology of traumatic brain injury. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; Volume 127, pp. 45–66. [Google Scholar]McKee, A.C.; Daneshvar, D.H. The neuropathology of traumatic brain injury. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; Volume 127, pp. 45–66.

- Werner, C.; Engelhard, K. Pathophysiology of traumatic brain injury. BJA Br. J. Anaesth. 2007, 99, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Werner, C.; Engelhard, K. Pathophysiology of traumatic brain injury. BJA Br. J. Anaesth. 2007, 99, 4–9.

- Sulhan, S.; Lyon, K.A.; Shapiro, L.A.; Huang, J.H. Neuroinflammation and blood–brain barrier disruption following traumatic brain injury: Pathophysiology and potential therapeutic targets. J. Neurosci. Res. 2020, 98, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Sulhan, S.; Lyon, K.A.; Shapiro, L.A.; Huang, J.H. Neuroinflammation and blood–brain barrier disruption following traumatic brain injury: Pathophysiology and potential therapeutic targets. J. Neurosci. Res. 2020, 98, 19–28.

- Henry, R.J.; Doran, S.J.; Barrett, J.P.; Meadows, V.E.; Sabirzhanov, B.; Stoica, B.A.; Loane, D.J.; Faden, A.I. Inhibition of miR-155 limits neuroinflammation and improves functional recovery after experimental traumatic brain injury in mice. Neurotherapeutics 2019, 16, 216–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Henry, R.J.; Doran, S.J.; Barrett, J.P.; Meadows, V.E.; Sabirzhanov, B.; Stoica, B.A.; Loane, D.J.; Faden, A.I. Inhibition of miR-155 limits neuroinflammation and improves functional recovery after experimental traumatic brain injury in mice. Neurotherapeutics 2019, 16, 216–230.

- Long, X.; Yao, X.; Jiang, Q.; Yang, Y.; He, X.; Tian, W.; Zhao, K.; Zhang, H. Astrocyte-derived exosomes enriched with miR-873a-5p inhibit neuroinflammation via microglia phenotype modulation after traumatic brain injury. J. Neuroinflamm. 2020, 17, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Long, X.; Yao, X.; Jiang, Q.; Yang, Y.; He, X.; Tian, W.; Zhao, K.; Zhang, H. Astrocyte-derived exosomes enriched with miR-873a-5p inhibit neuroinflammation via microglia phenotype modulation after traumatic brain injury. J. Neuroinflamm. 2020, 17, 1–15.

- Sims, G.P.; Rowe, D.C.; Rietdijk, S.T.; Herbst, R.; Coyle, A.J. HMGB1 and RAGE in inflammation and cancer. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2009, 28, 367–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Sims, G.P.; Rowe, D.C.; Rietdijk, S.T.; Herbst, R.; Coyle, A.J. HMGB1 and RAGE in inflammation and cancer. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2009, 28, 367–388.

- Aucott, H.; Lundberg, J.; Salo, H.; Klevenvall, L.; Damberg, P.; Ottosson, L.; Andersson, U.; Holmin, S.; Harris, H.E. Neuroinflammation in response to intracerebral injections of different HMGB1 redox isoforms. J. Innate Immun. 2018, 10, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Aucott, H.; Lundberg, J.; Salo, H.; Klevenvall, L.; Damberg, P.; Ottosson, L.; Andersson, U.; Holmin, S.; Harris, H.E. Neuroinflammation in response to intracerebral injections of different HMGB1 redox isoforms. J. Innate Immun. 2018, 10, 215–227.

- Okuma, Y.; Liu, K.; Wake, H.; Zhang, J.; Maruo, T.; Date, I.; Yoshino, T.; Ohtsuka, A.; Otani, N.; Tomura, S. Anti–high mobility group box-1 antibody therapy for traumatic brain injury. Ann. Neurol. 2012, 72, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Okuma, Y.; Liu, K.; Wake, H.; Zhang, J.; Maruo, T.; Date, I.; Yoshino, T.; Ohtsuka, A.; Otani, N.; Tomura, S. Anti–high mobility group box-1 antibody therapy for traumatic brain injury. Ann. Neurol. 2012, 72, 373–384.

- Haruma, J.; Teshigawara, K.; Hishikawa, T.; Wang, D.; Liu, K.; Wake, H.; Mori, S.; Takahashi, H.K.; Sugiu, K.; Date, I. Anti-high mobility group box-1 (HMGB1) antibody attenuates delayed cerebral vasospasm and brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 37755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Haruma, J.; Teshigawara, K.; Hishikawa, T.; Wang, D.; Liu, K.; Wake, H.; Mori, S.; Takahashi, H.K.; Sugiu, K.; Date, I. Anti-high mobility group box-1 (HMGB1) antibody attenuates delayed cerebral vasospasm and brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 37755.

- Fu, L.; Liu, K.; Wake, H.; Teshigawara, K.; Yoshino, T.; Takahashi, H.; Mori, S.; Nishibori, M. Therapeutic effects of anti-HMGB1 monoclonal antibody on pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus in mice. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Fu, L.; Liu, K.; Wake, H.; Teshigawara, K.; Yoshino, T.; Takahashi, H.; Mori, S.; Nishibori, M. Therapeutic effects of anti-HMGB1 monoclonal antibody on pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus in mice. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–13.

- Fujita, K.; Motoki, K.; Tagawa, K.; Chen, X.; Hama, H.; Nakajima, K.; Homma, H.; Tamura, T.; Watanabe, H.; Katsuno, M. HMGB1, a pathogenic molecule that induces neurite degeneration via TLR4-MARCKS, is a potential therapeutic target for Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Fujita, K.; Motoki, K.; Tagawa, K.; Chen, X.; Hama, H.; Nakajima, K.; Homma, H.; Tamura, T.; Watanabe, H.; Katsuno, M. HMGB1, a pathogenic molecule that induces neurite degeneration via TLR4-MARCKS, is a potential therapeutic target for Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 1–15.

- Coco, D.L.; Veglianese, P.; Allievi, E.; Bendotti, C. Distribution and cellular localization of high mobility group box protein 1 (HMGB1) in the spinal cord of a transgenic mouse model of ALS. Neurosci. Lett. 2007, 412, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Coco, D.L.; Veglianese, P.; Allievi, E.; Bendotti, C. Distribution and cellular localization of high mobility group box protein 1 (HMGB1) in the spinal cord of a transgenic mouse model of ALS. Neurosci. Lett. 2007, 412, 73–77.

- Paudel, Y.N.; Angelopoulou, E.; Piperi, C.; Othman, I.; Shaikh, M.F. Implication of HMGB1 signaling pathways in Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS): From molecular mechanisms to pre-clinical results. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 156, 104792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Paudel, Y.N.; Angelopoulou, E.; Piperi, C.; Othman, I.; Shaikh, M.F. Implication of HMGB1 signaling pathways in Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS): From molecular mechanisms to pre-clinical results. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 156, 104792.

- Sasaki, T.; Liu, K.; Agari, T.; Yasuhara, T.; Morimoto, J.; Okazaki, M.; Takeuchi, H.; Toyoshima, A.; Sasada, S.; Shinko, A. Anti-high mobility group box 1 antibody exerts neuroprotection in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease. Exp. Neurol. 2016, 275, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Sasaki, T.; Liu, K.; Agari, T.; Yasuhara, T.; Morimoto, J.; Okazaki, M.; Takeuchi, H.; Toyoshima, A.; Sasada, S.; Shinko, A. Anti-high mobility group box 1 antibody exerts neuroprotection in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease. Exp. Neurol. 2016, 275, 220–231.

- Gao, T.-L.; Yuan, X.-T.; Yang, D.; Dai, H.-L.; Wang, W.-J.; Peng, X.; Shao, H.-J.; Jin, Z.-F.; Fu, Z.-J. Expression of HMGB1 and RAGE in rat and human brains after traumatic brain injury. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012, 72, 643–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Gao, T.-L.; Yuan, X.-T.; Yang, D.; Dai, H.-L.; Wang, W.-J.; Peng, X.; Shao, H.-J.; Jin, Z.-F.; Fu, Z.-J. Expression of HMGB1 and RAGE in rat and human brains after traumatic brain injury. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012, 72, 643–649.

- Chen, X.; Zhang, J.; Kim, B.; Jaitpal, S.; Meng, S.S.; Adjepong, K.; Imamura, S.; Wake, H.; Nishibori, M.; Stopa, E.G. High-mobility group box-1 translocation and release after hypoxic ischemic brain injury in neonatal rats. Exp. Neurol. 2019, 311, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Chen, X.; Zhang, J.; Kim, B.; Jaitpal, S.; Meng, S.S.; Adjepong, K.; Imamura, S.; Wake, H.; Nishibori, M.; Stopa, E.G. High-mobility group box-1 translocation and release after hypoxic ischemic brain injury in neonatal rats. Exp. Neurol. 2019, 311, 1–14.

- Webster, K.M.; Shultz, S.R.; Ozturk, E.; Dill, L.K.; Sun, M.; Casillas-Espinosa, P.; Jones, N.C.; Crack, P.J.; O’Brien, T.J.; Semple, B.D. Targeting high-mobility group box protein 1 (HMGB1) in pediatric traumatic brain injury: Chronic neuroinflammatory, behavioral, and epileptogenic consequences. Exp. Neurol. 2019, 320, 112979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Webster, K.M.; Shultz, S.R.; Ozturk, E.; Dill, L.K.; Sun, M.; Casillas-Espinosa, P.; Jones, N.C.; Crack, P.J.; O’Brien, T.J.; Semple, B.D. Targeting high-mobility group box protein 1 (HMGB1) in pediatric traumatic brain injury: Chronic neuroinflammatory, behavioral, and epileptogenic consequences. Exp. Neurol. 2019, 320, 112979.

- Webster, K.M.; Sun, M.; Crack, P.J.; O’Brien, T.J.; Shultz, S.R.; Semple, B.D. Age-dependent release of high-mobility group box protein-1 and cellular neuroinflammation after traumatic brain injury in mice. J. Comp. Neurol. 2019, 527, 1102–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Webster, K.M.; Sun, M.; Crack, P.J.; O’Brien, T.J.; Shultz, S.R.; Semple, B.D. Age-dependent release of high-mobility group box protein-1 and cellular neuroinflammation after traumatic brain injury in mice. J. Comp. Neurol. 2019, 527, 1102–1117.

- Andersson, U.; Yang, H.; Harris, H. Extracellular HMGB1 as a therapeutic target in inflammatory diseases. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2018, 22, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Andersson, U.; Yang, H.; Harris, H. Extracellular HMGB1 as a therapeutic target in inflammatory diseases. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2018, 22, 263–277.

- Paudel, Y.N.; Angelopoulou, E.; Piperi, C.; Balasubramaniam, V.R.; Othman, I.; Shaikh, M.F. Enlightening the role of high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) in inflammation: Updates on receptor signalling. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 858, 172487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, U.; Yang, H.; Harris, H. High-mobility group box 1 protein (HMGB1) operates as an alarmin outside as well as inside cells. Semin. Immunol. 2018, 38, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Andersson, U.; Yang, H.; Harris, H. High-mobility group box 1 protein (HMGB1) operates as an alarmin outside as well as inside cells. Semin. Immunol. 2018, 38, 40–48.

- O’Connor, K.A.; Hansen, M.K.; Pugh, C.R.; Deak, M.M.; Biedenkapp, J.C.; Milligan, E.D.; Johnson, J.D.; Wang, H.; Maier, S.F.; Tracey, K.J. Further characterization of high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) as a proinflammatory cytokine: Central nervous system effects. Cytokine 2003, 24, 254–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]O’Connor, K.A.; Hansen, M.K.; Pugh, C.R.; Deak, M.M.; Biedenkapp, J.C.; Milligan, E.D.; Johnson, J.D.; Wang, H.; Maier, S.F.; Tracey, K.J. Further characterization of high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) as a proinflammatory cytokine: Central nervous system effects. Cytokine 2003, 24, 254–265.

- Hori, O.; Brett, J.; Slattery, T.; Cao, R.; Zhang, J.; Chen, J.X.; Nagashima, M.; Lundh, E.R.; Vijay, S.; Nitecki, D. The receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) is a cellular binding site for amphoterin mediation of neurite outgrowth and co-expression of rage and amphoterin in the developing nervous system. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 25752–25761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Hori, O.; Brett, J.; Slattery, T.; Cao, R.; Zhang, J.; Chen, J.X.; Nagashima, M.; Lundh, E.R.; Vijay, S.; Nitecki, D. The receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) is a cellular binding site for amphoterin mediation of neurite outgrowth and co-expression of rage and amphoterin in the developing nervous system. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 25752–25761.

- Yang, H.; Lundbäck, P.; Ottosson, L.; Erlandsson-Harris, H.; Venereau, E.; Bianchi, M.E.; Al-Abed, Y.; Andersson, U.; Tracey, K.J.; Antoine, D.J. Redox modification of cysteine residues regulates the cytokine activity of high mobility group box-1 (HMGB1). Mol. Med. 2012, 18, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Yang, H.; Lundbäck, P.; Ottosson, L.; Erlandsson-Harris, H.; Venereau, E.; Bianchi, M.E.; Al-Abed, Y.; Andersson, U.; Tracey, K.J.; Antoine, D.J. Redox modification of cysteine residues regulates the cytokine activity of high mobility group box-1 (HMGB1). Mol. Med. 2012, 18, 250–259.

- Yang, H.; Wang, H.; Ju, Z.; Ragab, A.A.; Lundbäck, P.; Long, W.; Valdes-Ferrer, S.I.; He, M.; Pribis, J.P.; Li, J. MD-2 is required for disulfide HMGB1–dependent TLR4 signaling. J. Exp. Med. 2015, 212, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Yang, H.; Wang, H.; Ju, Z.; Ragab, A.A.; Lundbäck, P.; Long, W.; Valdes-Ferrer, S.I.; He, M.; Pribis, J.P.; Li, J. MD-2 is required for disulfide HMGB1–dependent TLR4 signaling. J. Exp. Med. 2015, 212, 5–14.

- Palmblad, K.; Schierbeck, H.; Sundberg, E.; Horne, A.-C.; Harris, H.E.; Henter, J.-I.; Antoine, D.J.; Andersson, U. High systemic levels of the cytokine-inducing HMGB1 isoform secreted in severe macrophage activation syndrome. Mol. Med. 2014, 20, 538–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Palmblad, K.; Schierbeck, H.; Sundberg, E.; Horne, A.-C.; Harris, H.E.; Henter, J.-I.; Antoine, D.J.; Andersson, U. High systemic levels of the cytokine-inducing HMGB1 isoform secreted in severe macrophage activation syndrome. Mol. Med. 2014, 20, 538–547.

- Venereau, E.; Casalgrandi, M.; Schiraldi, M.; Antoine, D.J.; Cattaneo, A.; De Marchis, F.; Liu, J.; Antonelli, A.; Preti, A.; Raeli, L. Mutually exclusive redox forms of HMGB1 promote cell recruitment or proinflammatory cytokine release. J. Exp. Med. 2012, 209, 1519–1528.

- Uzawa, A.; Mori, M.; Taniguchi, J.; Masuda, S.; Muto, M.; Kuwabara, S. Anti-high mobility group box 1 monoclonal antibody ameliorates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2013, 172, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Uzawa, A.; Mori, M.; Taniguchi, J.; Masuda, S.; Muto, M.; Kuwabara, S. Anti-high mobility group box 1 monoclonal antibody ameliorates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2013, 172, 37–43.

- Zhao, J.; Wang, Y.; Xu, C.; Liu, K.; Wang, Y.; Chen, L.; Wu, X.; Gao, F.; Guo, Y.; Zhu, J. Therapeutic potential of an anti-high mobility group box-1 monoclonal antibody in epilepsy. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2017, 64, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Zhao, J.; Wang, Y.; Xu, C.; Liu, K.; Wang, Y.; Chen, L.; Wu, X.; Gao, F.; Guo, Y.; Zhu, J. Therapeutic potential of an anti-high mobility group box-1 monoclonal antibody in epilepsy. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2017, 64, 308–319.

- Mollica, L.; De Marchis, F.; Spitaleri, A.; Dallacosta, C.; Pennacchini, D.; Zamai, M.; Agresti, A.; Trisciuoglio, L.; Musco, G.; Bianchi, M.E. Glycyrrhizin binds to high-mobility group box 1 protein and inhibits its cytokine activities. Chem. Biol. 2007, 14, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Mollica, L.; De Marchis, F.; Spitaleri, A.; Dallacosta, C.; Pennacchini, D.; Zamai, M.; Agresti, A.; Trisciuoglio, L.; Musco, G.; Bianchi, M.E. Glycyrrhizin binds to high-mobility group box 1 protein and inhibits its cytokine activities. Chem. Biol. 2007, 14, 431–441.

- Davé, S.H.; Tilstra, J.S.; Matsuoka, K.; Li, F.; DeMarco, R.A.; Beer-Stolz, D.; Sepulveda, A.R.; Fink, M.P.; Lotze, M.T.; Plevy, S.E. Ethyl pyruvate decreases HMGB1 release and ameliorates murine colitis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2009, 86, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Davé, S.H.; Tilstra, J.S.; Matsuoka, K.; Li, F.; DeMarco, R.A.; Beer-Stolz, D.; Sepulveda, A.R.; Fink, M.P.; Lotze, M.T.; Plevy, S.E. Ethyl pyruvate decreases HMGB1 release and ameliorates murine colitis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2009, 86, 633–643.

- Nishibori, M.; Mori, S.; Takahashi, H.K. Anti-HMGB1 monoclonal antibody therapy for a wide range of CNS and PNS diseases. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2019, 140, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Nishibori, M.; Mori, S.; Takahashi, H.K. Anti-HMGB1 monoclonal antibody therapy for a wide range of CNS and PNS diseases. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2019, 140, 94–101.

- Paudel, Y.N.; Angelopoulou, E.; Semple, B.; Piperi, C.; Othman, I.; Shaikh, M.F. Potential neuroprotective effect of the HMGB1 inhibitor Glycyrrhizin in neurological disorders. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2020, 11, 485–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Paudel, Y.N.; Angelopoulou, E.; Semple, B.; Piperi, C.; Othman, I.; Shaikh, M.F. Potential neuroprotective effect of the HMGB1 inhibitor Glycyrrhizin in neurological disorders. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2020, 11, 485–500.

- Okuma, Y.; Wake, H.; Teshigawara, K.; Takahashi, Y.; Hishikawa, T.; Yasuhara, T.; Mori, S.; Takahashi, H.K.; Date, I.; Nishibori, M. Anti–High Mobility Group Box 1 Antibody Therapy May Prevent Cognitive Dysfunction After Traumatic Brain Injury. World Neurosurg. 2019, 122, e864–e871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Okuma, Y.; Wake, H.; Teshigawara, K.; Takahashi, Y.; Hishikawa, T.; Yasuhara, T.; Mori, S.; Takahashi, H.K.; Date, I.; Nishibori, M. Anti–High Mobility Group Box 1 Antibody Therapy May Prevent Cognitive Dysfunction After Traumatic Brain Injury. World Neurosurg. 2019, 122, e864–e871.

- Wang, D.; Liu, K.; Wake, H.; Teshigawara, K.; Mori, S.; Nishibori, M. Anti-high mobility group box-1 (HMGB1) antibody inhibits hemorrhage-induced brain injury and improved neurological deficits in rats. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 46243.

- Xiangjin, G.; Jin, X.; Banyou, M.; Gong, C.; Peiyuan, G.; Dong, W.; Weixing, H. Effect of glycyrrhizin on traumatic brain injury in rats and its mechanism. Chin. J. Traumatol. 2014, 17, 1–7.

- Okuma, Y.; Liu, K.; Wake, H.; Liu, R.; Nishimura, Y.; Hui, Z.; Teshigawara, K.; Haruma, J.; Yamamoto, Y.; Yamamoto, H. Glycyrrhizin inhibits traumatic brain injury by reducing HMGB1–RAGE interaction. Neuropharmacology 2014, 85, 18–26.

- Gao, T.; Chen, Z.; Chen, H.; Yuan, H.; Wang, Y.; Peng, X.; Wei, C.; Yang, J.; Xu, C. Inhibition of HMGB1 mediates neuroprotection of traumatic brain injury by modulating the microglia/macrophage polarization. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 497, 430–436.

- Qiu, X.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, J.; Yuan, C.; Zhao, M.; Yang, X. Ethyl pyruvate confers protection against endotoxemia and sepsis by inhibiting caspase-11-dependent cell pyroptosis. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2020, 78, 106016.

- Zhang, T.; Guan, X.-W.; Gribben, J.G.; Liu, F.-T.; Jia, L. Blockade of HMGB1 signaling pathway by ethyl pyruvate inhibits tumor growth in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Zhang, T.; Guan, X.-W.; Gribben, J.G.; Liu, F.-T.; Jia, L. Blockade of HMGB1 signaling pathway by ethyl pyruvate inhibits tumor growth in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 1–15.

- Bhat, S.M.; Massey, N.; Karriker, L.A.; Singh, B.; Charavaryamath, C. Ethyl pyruvate reduces organic dust-induced airway inflammation by targeting HMGB1-RAGE signaling. Respir. Res. 2019, 20, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Bhat, S.M.; Massey, N.; Karriker, L.A.; Singh, B.; Charavaryamath, C. Ethyl pyruvate reduces organic dust-induced airway inflammation by targeting HMGB1-RAGE signaling. Respir. Res. 2019, 20, 27.

- Ji, J.; Fu, T.; Dong, C.; Zhu, W.; Yang, J.; Kong, X.; Zhang, Z.; Bao, Y.; Zhao, R.; Ge, X. Targeting HMGB1 by ethyl pyruvate ameliorates systemic lupus erythematosus and reverses the senescent phenotype of bone marrow-mesenchymal stem cells. Aging 2019, 11, 4338.

- Su, X.; Wang, H.; Zhao, J.; Pan, H.; Mao, L. Beneficial effects of ethyl pyruvate through inhibiting high-mobility group box 1 expression and TLR4/NF-B pathway after traumatic brain injury in the rat. Mediat. Inflamm. 2011, 2011.

- Evran, S.; Calis, F.; Akkaya, E.; Baran, O.; Cevik, S.; Katar, S.; Gurevin, E.G.; Hanimoglu, H.; Hatiboglu, M.A.; Armutak, E.I. The effect of high mobility group box-1 protein on cerebral edema, blood-brain barrier, oxidative stress and apoptosis in an experimental traumatic brain injury model. Brain Res. Bull. 2020, 154, 68–80。

- Calder, P.C. Omega-3 fatty acids and inflammatory processes: From molecules to man. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2017, 45, 1105–1115.

- Bailes, J.E.; Abusuwwa, R.; Arshad, M.; Chowdhry, S.A.; Schleicher, D.; Hempeck, N.; Gandhi, Y.N.; Jaffa, Z.; Bokhari, F.; Karahalios, D. Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation in severe brain trauma: Case for a large multicenter trial. J. Neurosurg. 2020, 1, 1–5.

- Chen, X.; Wu, S.; Chen, C.; Xie, B.; Fang, Z.; Hu, W.; Chen, J.; Fu, H.; He, H. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation attenuates microglial-induced inflammation by inhibiting the HMGB1/TLR4/NF-κB pathway following experimental traumatic brain injury. J. Neuroinflamm. 2017, 14, 143.

- Chen, X.; Chen, C.; Fan, S.; Wu, S.; Yang, F.; Fang, Z.; Fu, H.; Li, Y. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid attenuates the inflammatory response by modulating microglia polarization through SIRT1-mediated deacetylation of the HMGB1/NF-κB pathway following experimental traumatic brain injury. J. Neuroinflamm. 2018, 15, 116.

- Descotes, J. Immunotoxicity of monoclonal antibodies. MAbs 2009, 1, 104–111.

- Ohnishi, M.; Katsuki, H.; Fukutomi, C.; Takahashi, M.; Motomura, M.; Fukunaga, M.; Matsuoka, Y.; Isohama, Y.; Izumi, Y.; Kume, T. HMGB1 inhibitor glycyrrhizin attenuates intracerebral hemorrhage-induced injury in rats. Neuropharmacology 2011, 61, 975–980.

- Pang, H.; Huang, T.; Song, J.; Li, D.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, X. Inhibiting HMGB1 with glycyrrhizic acid protects brain injury after DAI via its anti-inflammatory effect. Mediat. Inflamm. 2016, 2016.

- Simon, D.W.; Aneja, R.K.; Alexander, H.; Bell, M.J.; Bayır, H.; Kochanek, P.M.; Clark, R.S. Minocycline attenuates high mobility group box 1 translocation, microglial activation, and thalamic neurodegeneration after traumatic brain injury in post-natal day 17 rats. J. Neurotrauma 2018, 35, 130–138.

- Sehba, F.A.; Hou, J.; Pluta, R.M.; Zhang, J.H. The importance of early brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Prog. Neurobiol. 2012, 97, 14–37.

- Sun, X.; Ji, C.; Hu, T.; Wang, Z.; Chen, G. Tamoxifen as an effective neuroprotectant against early brain injury and learning deficits induced by subarachnoid hemorrhage: Possible involvement of inflammatory signaling. J. Neuroinflamm. 2013, 10, 920.

- Zhang, X.-S.; Li, W.; Wu, Q.; Wu, L.-Y.; Ye, Z.-N.; Liu, J.-P.; Zhuang, Z.; Zhou, M.-L.; Zhang, X.; Hang, C.-H. Resveratrol attenuates acute inflammatory injury in experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats via inhibition of TLR4 pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1331.

- Ieong, C.; Sun, H.; Wang, Q.; Ma, J. Glycyrrhizin suppresses the expressions of HMGB1 and ameliorates inflammative effect after acute subarachnoid hemorrhage in rat model. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2018, 47, 278–284.

- Li, Y.; Sun, F.; Jing, Z.; Wang, X.; Hua, X.; Wan, L. Glycyrrhizic acid exerts anti-inflammatory effect to improve cerebral vasospasm secondary to subarachnoid hemorrhage in a rat model. Neurol. Res. 2017, 39, 727–732.

- An, J.Y.; Pang, H.G.; Huang, T.Q.; Song, J.N.; Li, D.D.; Zhao, Y.L.; Ma, X.D. AG490 ameliorates early brain injury via inhibition of JAK2/STAT3-mediated regulation of HMGB1 in subarachnoid hemorrhage. Exp. Ther. Med. 2018, 15, 1330–1338.

- Zhang, X.-S.; Li, W.; Wu, Q.; Wu, L.-Y.; Ye, Z.-N.; Liu, J.-P.; Zhuang, Z.; Zhou, M.-L.; Zhang, X.; Hang, C.-H. Resveratrol attenuates acute inflammatory injury in experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats via inhibition of TLR4 pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Zhang, X.-S.; Li, W.; Wu, Q.; Wu, L.-Y.; Ye, Z.-N.; Liu, J.-P.; Zhuang, Z.; Zhou, M.-L.; Zhang, X.; Hang, C.-H. Resveratrol attenuates acute inflammatory injury in experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats via inhibition of TLR4 pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1331.

- Chang, C.-Z.; Lin, C.-L.; Wu, S.-C.; Kwan, A.-L. Purpurogallin, a natural phenol, attenuates high-mobility group box 1 in subarachnoid hemorrhage induced vasospasm in a rat model. Int. J. Vasc. Med. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Chang, C.-Z.; Lin, C.-L.; Wu, S.-C.; Kwan, A.-L. Purpurogallin, a natural phenol, attenuates high-mobility group box 1 in subarachnoid hemorrhage induced vasospasm in a rat model. Int. J. Vasc. Med. 2014.

- Chang, C.-Z.; Wu, S.-C.; Kwan, A.-L.; Lin, C.-L. Rhinacanthin-C, a fat-soluble extract from Rhinacanthus nasutus, modulates high-mobility group box 1-related neuro-inflammation and subarachnoid hemorrhage-induced brain apoptosis in a rat model. World Neurosurg. 2016, 86, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Chang, C.-Z.; Wu, S.-C.; Kwan, A.-L.; Lin, C.-L. Rhinacanthin-C, a fat-soluble extract from Rhinacanthus nasutus, modulates high-mobility group box 1-related neuro-inflammation and subarachnoid hemorrhage-induced brain apoptosis in a rat model. World Neurosurg. 2016, 86, 349–360.

- Wang, Z.; Wu, L.; You, W.; Ji, C.; Chen, G. Melatonin alleviates secondary brain damage and neurobehavioral dysfunction after experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage: Possible involvement of TLR 4-mediated inflammatory pathway. J. Pineal Res. 2013, 55, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Wang, Z.; Wu, L.; You, W.; Ji, C.; Chen, G. Melatonin alleviates secondary brain damage and neurobehavioral dysfunction after experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage: Possible involvement of TLR 4-mediated inflammatory pathway. J. Pineal Res. 2013, 55, 399–408.

- Wang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Liang, L.; Wu, Y.; Zhong, J.; Sun, X. Anti-high mobility group box-1 antibody attenuated vascular smooth muscle cell phenotypic switching and vascular remodelling after subarachnoid haemorrhage in rats. Neurosci. Lett. 2019, 708, 134338.

- Chang, C.-Z.; Wu, S.-C.; Kwan, A.-L. Glycyrrhizin attenuates proinflammatory cytokines through a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ-dependent mechanism and experimental vasospasm in a rat model. J. Vasc. Res. 2015, 52, 12–21.

- Chang, C.-Z.; Wu, S.-C.; Kwan, A.-L.; Lin, C.-L. 4′-O-β-d-glucosyl-5-O-methylvisamminol, an active ingredient of Saposhnikovia divaricata, attenuates high-mobility group box 1 and subarachnoid hemorrhage-induced vasospasm in a rat model. Behav. Brain Funct. 2015, 11, 28.

- Aneja, R.K.; Alcamo, A.M.; Cummings, J.; Vagni, V.; Feldman, K.; Wang, Q.; Dixon, C.E.; Billiar, T.R.; Kochanek, P.M. Lack of benefit on brain edema, blood–brain barrier permeability, or cognitive outcome in global inducible high mobility group box 1 knockout mice despite tissue sparing after experimental traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 2019, 36, 360–369.

- Yang, H.; Tracey, K.J. Targeting HMGB1 in inflammation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Gene Regul. Mech. 2010, 1799, 149–156.