This manuscript reviews the impact of tumor biology and molecular profiles on the management paradigm for BM patients and critically analyzes the current landscape of SRS, with a specific focus on integration with systemic therapy. We also discuss emerging treatment strategies combining SRS and ICIs, the impact of timing and the sequencing of these therapies around SRS, the effect of corticosteroids, and review post-treatment imaging findings, including pseudo-progression and radiation necrosis.

- stereotactic radiosurgery

- chemotherapy

- targeted therapy

- immunotherapy

- brain metastases

1. Introduction

Brain metastases (BM) represent the most common intracranial neoplasm in adults and occur in approximately 20–40% of all cancer patients [1]. The most common primary tumors in patients with BM are lung, breast, melanoma, colorectal, and renal, and these tumors are associated with a median survival time of 6–12 months [1]. BMs are distributed along regions of the brain with rich blood flow, with 80% occurring in the cerebral hemispheres, primarily at the grey-white junctional border [2]. Patients often develop symptoms consequential to the location of the tumor, either by direct tumor infiltration of critical functional regions, or due to the associated mass effect. Radiation therapy (RT), in the form of stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) or whole-brain radiotherapy (WBRT) is considered a mainstay anticancer modality in the treatment of BM from solid tumors [3]. However, the management of BM is based on patient and tumor-specific variables, such as tumor histology, performance status, prognosis, extent of extracranial disease, presence of targetable actionable mutations, number of lesions, volume of disease, symptoms, and patient preference [3].

The role of systemic therapy in the treatment of BM is evolving. Previously, its role was restricted due to variable CNS penetration of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and limited activity [4]. Targeted therapies with greater CNS penetration and improved efficacy have emerged in parallel with the identification of driver mutations, which have led to advances in drug discovery and development [5]. Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) represent another significant advancement in systemic therapy options for BM, as they have shown promising CNS activity in subsets of patients [5]. As a result, BM can now be managed with systemic therapy either prior to, concomitantly, or after RT, and various combinations of RT with systemic therapies are being explored to improve both local and extracranial disease control, as well as overall survival (OS). This necessitates effective management strategies from multidisciplinary teams, as treatment decisions must balance the risk of recurrence/progression with treatment-related side effects. Previous reviews have compiled data from retrospective and prospective studies of combination approaches [5][6]. However, in this review, we summarize the data from recent studies and clinical trials supporting the use of BM-directed systemic therapies, such as chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy, that have been completed or are currently being investigated, and their integration with SRS for the treatment of BM.

2. Modern Role for Stereotactic Radiosurgery

SRS is commonly utilized for patients with a disease-specific graded prognostic assessment (DS-GPA) [7] score over 2, low intracranial disease burden, and minimal neurological symptoms. When compared to WBRT, a phase III study reported that SRS produces a similar OS with less decline in neurocognitive function (WBRT plus SRS 53% vs. 20% SRS alone), but with a significantly increased risk of intracranial relapse [8]. SRS is preferred for patients with a limited number of BM (4 or fewer lesions) based on the results from randomized trials [9][10]. The radiation doses are based on tumor dimension, <2 cm, 2.1–3 cm and >3 cm are 24 Gy, 18 Gy and 15 Gy, respectively, based on the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) 90-05 study [11]. The efficacy of SRS appears to be independent of the primary tumor type, as radioresistant tumors (i.e., renal cell carcinoma and melanoma) have similar control rates as radiosensitive tumors (i.e., breast cancer and lung cancer) [12][13]. Single fraction SRS is not recommended for lesions > 4 cm due to an unacceptable level of toxicity [14]. However, hypofractionated SRS (HF-SRS) or staged SRS can be considered for larger lesions [14]. Fractionated SRS is typically delivered to 25–30 Gy over 3–5 fractions and is considered for lesions close to critical structures, such as the brainstem or the optic apparatus. Some centers utilize the concept of low overall intracranial disease burden based on total volume of all brain metastases (<15–30 cc) to select patients to be treated with SRS; however, this parameter has not been defined adequately and requires prospective validation [4].

In the context of post-operative RT, SRS has replaced WBRT in most instances, but the issue of the optimal interval between surgery and SRS remains ill-defined [15][16]. Further, several reports suggest that pre-operative SRS reduces the risk of meningeal metastases and symptomatic radiation necrosis (RN) compared to post-operative SRS [17][18]. Pre-operative SRS allows for better target volume delineation, as opposed to a poorly-defined irregularly shaped surgical cavity in the post-operative setting. It also allows for better tumor control by reducing the intra-operative seeding of viable tumor cells outside the treated cavity, hence decreasing the risk of leptomeningeal disease [19]. The rate of symptomatic RN may be reduced with pre-operative SRS as target delineation is better, less normal brain is irradiated, and the majority of the irradiated tissue is resected after SRS [18]. One major limitation of pre-operative SRS is the lack of pathological confirmation prior to SRS. Moreover, select reports demonstrate that pre-operative SRS has the potential to lead to increased wound healing complications [20].

In the post-operative setting, high dose HF-SRS provided greater local control (LC)—defined as radiographic evidence of stable disease, partial response, or complete response, as compared to lower biological effective dose (BED) regimens (95% vs. 59%) [21]. For example, 25 Gy in 5 fractions (BED10 of 37.5 Gy) was not adequate to control microscopic disease as compared to 30 Gy in 5 fractions (BED10 > 48 Gy) which had excellent tumor bed control. Similarly, another study reported that HF-SRS after resection of BM was well tolerated and had improved LC with BED10 ≥ 48 (i.e., 30 Gy/5 fractions and 27 Gy/3 fractions) [22].

The LC rates following SRS for 5 or more intracranial lesions are comparable to those for fewer lesions [23]; however, these patients continue to experience a high rate of distant intracranial failure, and therefore alternative treatment strategies, such as hippocampal-avoidant whole brain radiotherapy (HA-WBRT), should be considered. There is evolving evidence that primary SRS alone can be used in select patients with >10 lesions [24]. A phase III randomized trial of SRS vs. WBRT in 72 patients with 4–15 BMs (NCT01592968) has also been presented, and demonstrated that SRS was associated with a reduced risk of neurocognitive deterioration relative to WBRT without compromising OS, but clearly with higher risk of intracranial relapse [25]. A prospective phase III trial (NCT03550391) will compare stereotactic radiosurgery with HA-WBRT plus memantine for 5–15 brain metastases.

3. Stereotactic Radiosurgery and Systemic Therapies

There are limited data on the outcomes of concurrent chemotherapy with SRS for the treatment of BM. Cagney et al. reported the outcomes of patients treated with pemetrexed and SRS for lung cancer BM, and found that the combination was associated with a reduced likelihood of developing new brain metastases ( p = 0.006) and a reduced need for brain-directed salvage RT ( p = 0.005) [26]. However, the combination of pemetrexed and SRS was found to be associated with increase in radiographic RN (HR 2.70, 95% CI 1.09–6.70, p = 0.03). The authors concluded that patients who receive pemetrexed after brain-directed SRS tend to benefit from increased intracranial disease control at the potential cost of radiation-related RN. Shen and colleagues also demonstrated the safety of concurrent chemotherapy and SRS in 193 patients, of whom 37% were delivered with concurrent systemic therapy [27]. Kim and colleagues evaluated the outcomes in 1650 patients who presented with 2843 intracranial metastases [28]; among these, 445 patients (27%) were treated with SRS and concurrent systemic therapy. The risk of RN in those treated with SRS and concurrent systemic therapy was not increased as compared to SRS alone (6.6% and 5.3%); however, concurrent systemic therapy was linked to a higher rate of radiographic RN in lesions treated with upfront SRS and WBRT (8.7 vs. 3.7%, p = 0.04). Further study is warranted to explore whether symptomatic RN occurs more frequently in patients receiving pemetrexed along with SRS, and detailed analyses of other systemic therapy combinations are clearly needed to inform clinical practice.

The use of targeted therapies in patients with actionable alterations represents a popular topic in BM research. Patients with these specific molecular subtypes respond to targeted therapies at higher rates than to chemotherapeutic agents or ICIs. As patients with BM have traditionally been excluded from clinical trials assessing systemic therapies in BM patients, the role of these systemic treatments, particularly when used in conjunction with SRS for BM, is unclear. This section summarizes the data regarding the combination of various targeted therapies with SRS.

The experience with small numbers of patients suggests that combining SRS with trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) might result in high rates of RN. In one study, SRS was given concurrently with T-DM1 in 4 patients, and sequentially in 8 patients [29]. The concurrent group had a 50% rate of RN while the sequential group had a 28.6% rate of RN. In a separate report, RN was observed in 40% of patients that received T-DM1 [30]. In contrast, Mills et al. reported that the combination of SRS and T-DM1 was well tolerated, with only 3% of patients reporting RN [31]. Hence, prospective studies to evaluate the ideal dose of SRS and timing of T-DM1 are warranted.

Several clinical trials are currently ongoing to evaluate and study the combination of SRS with various targeted agents for patients with BM, as summarized in Table 1 .

| Trial Registration No. | Study Location | Tumor Type | Study Design | Systemic Therapy Agent | n | Primary Endpoint | Study Start Date | Estimated Completion Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT04147728 | Peking University Third Hospital | NSCLC | Phase II | Anlotinib | 50 | EI | Dec 2019 | Dec 2022 |

| NCT04643847 | First People’s Hospital of Hangzhou | NSCLC | Phase II | Almonertinib | 47 | DOR | Nov 2020 | Nov 2023 |

| NCT02726568 | Betta Pharmaceuticals Co., Ltd. | NSCLC | Phase II | Icotinib | 30 | PFS | Mar 2016 | Dec 2022 |

| NCT03535363 | Case Comprehensive Cancer Center | NSCLC | Phase I | Osimertinib | 6 | MTD | Oct 2018 | Aug 2021 |

| NCT03769103 | British Columbia Cancer Agency | NSCLC | Phase II | Osimertinib | 76 | PFS | Mar 2019 | April 2025 |

| NCT03497767 | Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group | NSCLC | Phase II | Osimertinib | 80 | PFS | Aug 2019 | March 2024 |

| NCT04856475 | Jules Bordet Institute | Breast | Phase II | Neratinib | 104 | ORR | July 2021 | July 2025 |

| NCT03190967 | National Cancer Institute (NCI) | Breast | Phase I/II | T-DM1 and Metronomic Temozolomide | 125 | MTD | April 2018 | June 2023 |

| NCT04585724 | Emory University | Breast | Phase I | Abemaciclib, Ribociclib, or Palbociclib | 25 | AE | June 2020 | Oct 2021 |

| NCT04074096 | UNICANCER | Melanoma | Phase II | Binimetinib and Encorafenib | 150 | PFS | Sep 2021 | Sep 2028 |

| NCT03898908 | Grupo Español Multidisciplinar de Melanoma | Melanoma | Phase II | Binimetinib and Encorafenib | 38 | ORR | July 2019 | Oct 2023 |

| NCT03430947 | Technische Universität Dresden | Melanoma | Phase II | Vemurafenib and Cobimetinib | 20 | ORR | July 2018 | July 2022 |

| NCT02974803 | Canadian Cancer Trials Group | Melanoma | Phase II | Dabrafenib and Trametinib | 6 | ORR | Nov 2016 | June 2021 |

Abbreviations: n = number; NSCLC = non-small cell lung cancer; EI = edema index; DOR = duration of response; PFS = progression-free survival; AE = adverse events; MTD = maximum tolerated dose; RR = response rate; ORR = objective response rate.

4. SRS and Immunotherapy

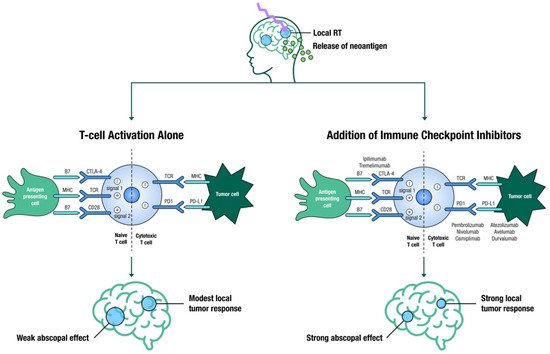

SRS is known to increase both innate and adaptive immune responses, making tumor cells more susceptible to T-cell-mediated killing [32] ( Figure 1 ). The aim is to evoke an immune response that will not only boost local effects but also lead to an abscopal response, which occurs outside of the irradiated area [32]. Large registry studies have demonstrated improved OS with SRS and ICIs in patients with BM [33], yet several questions regarding appropriate timing, fractionation, toxicities, and out-of-field responses remain unanswered, and thus several trials are attempting to address these knowledge gaps [34].

The optimal sequence for these modalities is still unclear, with conflicting published results [34]. Several studies suggest that SRS acts as an antigenic primer by releasing neoantigens from dying cancer cells, and the resultant activated T-cells are further stimulated by ICIs to sustain the immune response. Furthermore, SRS eradicates the inhibitory T-cells in the tumor microenvironment, which would otherwise dampen the immune response [35][36]. This hypothesis would suggest that close temporal sequencing of SRS and ICIs is required. Underscoring this hypothesis, ipilimumab before SRS resulted in a higher partial response rate as compared to ipilimumab administered after SRS (40% vs. 16.7%) [37]. However, a large retrospective study showed that neoadjuvant ICI had no additional advantage over adjuvant ICI [38].

The concept of concurrent treatment of ICI with to SRS is still up for debate, with some studies using a 2-week window while others extending this to 1 month [39]. Although the timing of SRS in relation to ICIs is likely to be influenced by the agent of choice and its half-life, as well as the mechanism of immune activation and response, it appears that ICIs given four weeks before or after SRS have shown the best results [40]. Prospective studies in BM patients are urgently needed to assess the timing and sequencing of ICIs with SRS ( Table 2 ).

| Trial Registration No. | Study Location | Tumor Type | Study Design | Immunotherapy Agent | n | Primary Endpoint | Study Start Date | Estimated Completion Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT03483012 | Dana-Farber Cancer Institute | Breast | Phase II | Atezolizumab | 45 | PFS | Sep 2021 | Sep 2025 |

| NCT03449238 | Weill Medical College of Cornell University | Breast | Phase II | Pembrolizumab | 41 | RR, OS | Nov 2018 | Dec 2026 |

| NCT03807765 | H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute | Breast | Phase I | Nivolumab | 14 | DLT | Jan 2019 | Jan 2022 |

| NCT02886585 | Massachusetts General Hospital | Any solid tumor | Phase II | Pembrolizumab | 102 | RR, OS | Oct 2016 | Sep 2022 |

| NCT02097732 | University of Michigan Rogel Cancer Center | Melanoma | Phase II | Ipilimumab | 40 | LC | April 2014 | July 2020 |

| NCT03340129 | Melanoma Institute Australia | Melanoma | Phase II | Nivolumab & Ipilimumab | 218 | NSCD | Aug 2019 | Aug 2025 |

| NCT03297463 | Masonic Cancer Center, University of Minnesota | Melanoma | Phase I/II | Ipilimumab | 40 | MTD, ORR | Jan 2018 | Feb 2020 |

| NCT02716948 | Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center | Melanoma | Phase I | Nivolumab | 90 | AE | Jun 2016 | Mar 2023 |

| NCT02858869 | Emory University | Melanoma, NSCLC | Phase I | Pembrolizumab | 30 | DLT | Oct 2016 | Oct 2021 |

| NCT02696993 | M.D. Anderson Cancer Center | NSCLC | Phase I/II | Nivolumab & Ipilimumab | 88 | DLT, PFS | Dec 2016 | Dec 2020 |

| NCT02978404 | Centre hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal (CHUM) | NSCLC, RCC | Phase II | Nivolumab | 26 | PFS | Jun 2017 | Jun 2022 |

The synergistic combination of SRS and ICIs also raises concerns about possible side effects, including pseudo-progression and RN [41]. Hubbeling et al. studied adverse radiation effects (AREs)—the imaging correlate of RN in relation to ICI treatment status, RT type, and timing of treatment [42]. They concluded that ICIs and RT did not increase the risk of AREs. On the other hand, Martin et al. evaluated the risk of RN in melanoma, NSCLC, or renal cell carcinoma BM in patients who received a combination of ICIs and RT [43], and discovered a correlation between the occurrence of symptomatic RN and the use of combination therapy, particularly in melanoma patients. Despite reports of an increased risk of RN in some studies, a meta-analysis of the published literature found no evidence of a higher risk than would be predicted with SRS alone [44]. Clearly, the databases for this approach are limited, and of modest quality, given their retrospective nature, and prospective randomized trials are required.

References

- Suh, J.H.; Kotecha, R.; Chao, S.T.; Ahluwalia, M.S.; Sahgal, A.; Chang, E.L. Current approaches to the management of brain metastases. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 17, 279–299.

- Hwang, T.L.; Close, T.P.; Grego, J.M.; Brannon, W.L.; Gonzales, F. Predilection of brain metastasis in gray and white matter junction and vascular border zones. Cancer 1996, 77, 1551–1555.

- Kotecha, R.; Gondi, V.; Ahluwalia, M.S.; Brastianos, P.K.; Mehta, M.P. Recent advances in managing brain metastasis. F1000Research 2018, 7.

- Palmer, J.D.; Trifiletti, D.M.; Gondi, V.; Chan, M.; Minniti, G.; Rusthoven, C.G.; Schild, S.E.; Mishra, M.V.; Bovi, J.; Williams, N.; et al. Multidisciplinary patient-centered management of brain metastases and future directions. Neuro-Oncol. Adv. 2020, 2, vdaa034.

- Borius, P.-Y.; Régis, J.; Carpentier, A.; Kalamarides, M.; Valery, C.A.; Latorzeff, I. Safety of radiosurgery concurrent with systemic therapy (chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and/or immunotherapy) in brain metastases: A systematic review. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2021, 40, 341–354.

- Liu, L.; Chen, W.; Zhang, R.; Wang, Y.; Liu, P.; Lian, X.; Zhang, F.; Wang, Y.; Ma, W. Radiotherapy in combination with systemic therapies for brain metastases: Current status and progress. Cancer Biol. Med. 2020, 17, 910–922.

- Sperduto, P.W.; Mesko, S.; Li, J.; Cagney, D.; Aizer, A.; Lin, N.U.; Nesbit, E.; Kruser, T.J.; Chan, J.; Braunstein, S.; et al. Survival in Patients With Brain Metastases: Summary Report on the Updated Diagnosis-Specific Graded Prognostic Assessment and Definition of the Eligibility Quotient. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 3773–3784.

- Brown, P.D.; Jaeckle, K.; Ballman, K.V.; Farace, E.; Cerhan, J.H.; Anderson, S.K.; Carrero, X.W.; Barker, F.G.; Deming, R.; Burri, S.H.; et al. Effect of Radiosurgery Alone vs Radiosurgery with Whole Brain Radiation Therapy on Cognitive Function in Patients With 1 to 3 Brain Metastases: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2016, 316, 401–409.

- Brown, P.D.; Ballman, K.V.; Cerhan, J.H.; Anderson, S.K.; Carrero, X.W.; Whitton, A.C.; Greenspoon, J.; Parney, I.F.; Laack, N.N.I.; Ashman, J.B.; et al. Postoperative stereotactic radiosurgery compared with whole brain radiotherapy for resected metastatic brain disease (NCCTG N107C/CEC·3): A multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 1049–1060.

- Aoyama, H.; Shirato, H.; Tago, M.; Nakagawa, K.; Toyoda, T.; Hatano, K.; Kenjyo, M.; Oya, N.; Hirota, S.; Shioura, H.; et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery plus whole-brain radiation therapy vs stereotactic radiosurgery alone for treatment of brain metastases: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2006, 295, 2483–2491.

- Shaw, E.; Scott, C.; Souhami, L.; Dinapoli, R.; Kline, R.; Loeffler, J.; Farnan, N. Single dose radiosurgical treatment of recurrent previously irradiated primary brain tumors and brain metastases: Final report of RTOG protocol 90-05. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2000, 47, 291–298.

- Chang, E.L.; Wefel, J.S.; Hess, K.R.; Allen, P.K.; Lang, F.F.; Kornguth, D.G.; Arbuckle, R.B.; Swint, J.M.; Shiu, A.S.; Maor, M.H.; et al. Neurocognition in patients with brain metastases treated with radiosurgery or radiosurgery plus whole-brain irradiation: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009, 10, 1037–1044.

- Gerosa, M.; Nicolato, A.; Foroni, R.; Tomazzoli, L.; Bricolo, A. Analysis of long-term outcomes and prognostic factors in patients with non-small cell lung cancer brain metastases treated by gamma knife radiosurgery. J. Neurosurg. 2005, 102, 75–80.

- Kotecha, R.; Mehta, M.P. The Complexity of Managing Large Brain Metastasis. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2019, 104, 483–484.

- Yusuf, M.B.; Amsbaugh, M.J.; Burton, E.; Nelson, M.; Williams, B.; Koutourousiou, M.; Nauta, H.; Woo, S. Increasing time to postoperative stereotactic radiation therapy for patients with resected brain metastases: Investigating clinical outcomes and identifying predictors associated with time to initiation. J. Neurooncol. 2018, 136, 545–553.

- Bander, E.D.; Yuan, M.; Reiner, A.S.; Panageas, K.S.; Ballangrud, Å.M.; Brennan, C.W.; Beal, K.; Tabar, V.; Moss, N.S. Durable 5-year local control for resected brain metastases with early adjuvant SRS: The effect of timing on intended-field control. Neuro-oncol. Pract. 2021, 8, 278–289.

- Patel, K.R.; Burri, S.H.; Asher, A.L.; Crocker, I.R.; Fraser, R.W.; Zhang, C.; Chen, Z.; Kandula, S.; Zhong, J.; Press, R.H.; et al. Comparing Preoperative With Postoperative Stereotactic Radiosurgery for Resectable Brain Metastases: A Multi-institutional Analysis. Neurosurgery 2016, 79, 279–285.

- Routman, D.M.; Yan, E.; Vora, S.; Peterson, J.; Mahajan, A.; Chaichana, K.L.; Laack, N.; Brown, P.D.; Parney, I.F.; Burns, T.C.; et al. Preoperative Stereotactic Radiosurgery for Brain Metastases. Front. Neurol. 2018, 9, 959.

- Iorio-Morin, C.; Masson-Côté, L.; Ezahr, Y.; Blanchard, J.; Ebacher, A.; Mathieu, D. Early Gamma Knife stereotactic radiosurgery to the tumor bed of resected brain metastasis for improved local control. J. Neurosurg. 2014, 121.

- Prabhu, R.S.; Patel, K.R.; Press, R.H.; Soltys, S.G.; Brown, P.D.; Mehta, M.P.; Asher, A.L.; Burri, S.H. Preoperative Vs Postoperative Radiosurgery For Resected Brain Metastases: A Review. Neurosurgery 2019, 84, 19–29.

- Musunuru, H.B.; Witt, J.S.; Yadav, P.; Francis, D.M.; Kuczmarska-Haas, A.; Labby, Z.E.; Bassetti, M.F.; Howard, S.P.; Baschnagel, A.M. Impact of adjuvant fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy dose on local control of brain metastases. J. Neurooncol. 2019, 145, 385–390.

- Kumar, A.M.S.; Miller, J.; Hoffer, S.A.; Mansur, D.B.; Coffey, M.; Lo, S.S.; Sloan, A.E.; Machtay, M. Postoperative hypofractionated stereotactic brain radiation (HSRT) for resected brain metastases: Improved local control with higher BED10. J. Neurooncol. 2018, 139, 449–454.

- Yamamoto, M.; Serizawa, T.; Shuto, T.; Akabane, A.; Higuchi, Y.; Kawagishi, J.; Yamanaka, K.; Sato, Y.; Jokura, H.; Yomo, S.; et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery for patients with multiple brain metastases (JLGK0901): A multi-institutional prospective observational study. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, 387–395.

- Hughes, R.T.; Masters, A.H.; McTyre, E.R.; Farris, M.K.; Chung, C.; Page, B.R.; Kleinberg, L.R.; Hepel, J.; Contessa, J.N.; Chiang, V.; et al. Initial SRS for Patients With 5 to 15 Brain Metastases: Results of a Multi-Institutional Experience. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2019, 104, 1091–1098.

- Li, J.; Ludmir, E.B.; Wang, Y.; Guha-Thakurta, N.; McAleer, M.F.; Settle, S.H.; Yeboa, D.N.; Ghia, A.J.; McGovern, S.L.; Chung, C.; et al. Stereotactic Radiosurgery versus Whole-brain Radiation Therapy for Patients with 4–15 Brain Metastases: A Phase III Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2020, 108, S21–S22.

- Cagney, D.N.; Martin, A.M.; Catalano, P.J.; Reitman, Z.J.; Mezochow, G.A.; Lee, E.Q.; Wen, P.Y.; Weiss, S.E.; Brown, P.D.; Ahluwalia, M.S.; et al. Impact of pemetrexed on intracranial disease control and radiation necrosis in patients with brain metastases from non-small cell lung cancer receiving stereotactic radiation. Radiother. Oncol. 2018, 126, 511–518.

- Shen, C.J.; Kummerlowe, M.N.; Redmond, K.J.; Rigamonti, D.; Lim, M.K.; Kleinberg, L.R. Stereotactic Radiosurgery: Treatment of Brain Metastasis Without Interruption of Systemic Therapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2016, 95, 735–742.

- Kim, J.M.; Miller, J.A.; Kotecha, R.; Xiao, R.; Juloori, A.; Ward, M.C.; Ahluwalia, M.S.; Mohammadi, A.M.; Peereboom, D.M.; Murphy, E.S.; et al. The risk of radiation necrosis following stereotactic radiosurgery with concurrent systemic therapies. J. Neurooncol. 2017, 133, 357–368.

- Geraud, A.; Xu, H.P.; Beuzeboc, P.; Kirova, Y.M. Preliminary experience of the concurrent use of radiosurgery and T-DM1 for brain metastases in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. J. Neurooncol. 2017, 131, 69–72.

- Stumpf, P.K.; Cittelly, D.M.; Robin, T.P.; Carlson, J.A.; Stuhr, K.A.; Contreras-Zarate, M.J.; Lai, S.; Ormond, D.R.; Rusthoven, C.G.; Gaspar, L.E.; et al. Combination of Trastuzumab Emtansine and Stereotactic Radiosurgery Results in High Rates of Clinically Significant Radionecrosis and Dysregulation of Aquaporin-4. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 3946–3953.

- Mills, M.N.; Walker, C.; Thawani, C.; Naz, A.; Figura, N.B.; Kushchayev, S.; Etame, A.; Yu, H.-H.M.; Robinson, T.J.; Liu, J.; et al. Trastuzumab Emtansine (T-DM1) and stereotactic radiation in the management of HER2+ breast cancer brain metastases. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 223.

- ElJalby, M.; Pannullo, S.C.; Schwartz, T.H.; Parashar, B.; Wernicke, A.G. Optimal Timing and Sequence of Immunotherapy When Combined with Stereotactic Radiosurgery in the Treatment of Brain Metastases. World Neurosurg. 2019, 127, 397–404.

- Amaral, T.; Kiecker, F.; Schaefer, S.; Stege, H.; Kaehler, K.; Terheyden, P.; Gesierich, A.; Gutzmer, R.; Haferkamp, S.; Uttikal, J.; et al. Combined immunotherapy with nivolumab and ipilimumab with and without local therapy in patients with melanoma brain metastasis: A DeCOG* study in 380 patients. J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8.

- Ramakrishna, R.; Formenti, S. Radiosurgery and Immunotherapy in the Treatment of Brain Metastases. World Neurosurg. 2019, 130, 615–622.

- Tazi, K.; Hathaway, A.; Chiuzan, C.; Shirai, K. Survival of melanoma patients with brain metastases treated with ipilimumab and stereotactic radiosurgery. Cancer Med. 2015, 4, 1–6.

- Patel, K.R.; Shoukat, S.; Oliver, D.E.; Chowdhary, M.; Rizzo, M.; Lawson, D.H.; Khosa, F.; Liu, Y.; Khan, M.K. Ipilimumab and Stereotactic Radiosurgery Versus Stereotactic Radiosurgery Alone for Newly Diagnosed Melanoma Brain Metastases. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 40, 444–450.

- Silk, A.W.; Bassetti, M.F.; West, B.T.; Tsien, C.I.; Lao, C.D. Ipilimumab and radiation therapy for melanoma brain metastases. Cancer Med. 2013, 2, 899–906.

- Kotecha, R.; Kim, J.M.; Miller, J.A.; Juloori, A.; Chao, S.T.; Murphy, E.S.; Peereboom, D.M.; Mohammadi, A.M.; Barnett, G.H.; Vogelbaum, M.A.; et al. The impact of sequencing PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors and stereotactic radiosurgery for patients with brain metastasis. Neuro Oncol. 2019, 21, 1060–1068.

- Qian, J.M.; Yu, J.B.; Kluger, H.M.; Chiang, V.L.S. Timing and type of immune checkpoint therapy affect the early radiographic response of melanoma brain metastases to stereotactic radiosurgery. Cancer 2016, 122, 3051–3058.

- Skrepnik, T.; Sundararajan, S.; Cui, H.; Stea, B. Improved time to disease progression in the brain in patients with melanoma brain metastases treated with concurrent delivery of radiosurgery and ipilimumab. Oncoimmunology 2017, 6, e1283461.

- Vellayappan, B.; Tan, C.L.; Yong, C.; Khor, L.K.; Koh, W.Y.; Yeo, T.T.; Detsky, J.; Lo, S.; Sahgal, A. Diagnosis and Management of Radiation Necrosis in Patients With Brain Metastases. Front. Oncol. 2018, 8, 395.

- Hubbeling, H.G.; Schapira, E.F.; Horick, N.K.; Goodwin, K.E.H.; Lin, J.J.; Oh, K.S.; Shaw, A.T.; Mehan, W.A.; Shih, H.A.; Gainor, J.F. Safety of Combined PD-1 Pathway Inhibition and Intracranial Radiation Therapy in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2018, 13, 550–558.

- Martin, A.M.; Cagney, D.N.; Catalano, P.J.; Alexander, B.M.; Redig, A.J.; Schoenfeld, J.D.; Aizer, A.A. Immunotherapy and Symptomatic Radiation Necrosis in Patients With Brain Metastases Treated With Stereotactic Radiation. JAMA Oncol. 2018, 4, 1123–1124.

- Lehrer, E.J.; Peterson, J.; Brown, P.D.; Sheehan, J.P.; Quiñones-Hinojosa, A.; Zaorsky, N.G.; Trifiletti, D.M. Treatment of brain metastases with stereotactic radiosurgery and immune checkpoint inhibitors: An international meta-analysis of individual patient data. Radiother. Oncol. 2019, 130, 104–112.