The liver plays a key role in lipid homeostasis, with steps including the synthesis, oxidation, and transport of free fatty acids (FFA), triglycerides (TG), cholesterol, and bile acids (BA). Chronic liver diseases encompass a spectrum of conditions ranging from metabolic to viral, alcohol-related diseases, drug-related diseases, autoimmune diseases, and tumours. The hepatocyte can be damaged by various hits and intracellular organelles can be part of the dysfunctional cell, with changes including microsomal hypertrophy, mitochondrial damage by free fatty acids overload and insufficient β-oxidation and activation of peroxisomal metabolism.

Growing evidence points to dysfunctional mitochondria as key contributors in the pathogenesis of the chronic metabolic conditions (i.e., obesity, metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes mellitus) frequently linked to liver disease. These processes act through pathways leading to oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, and insulin resistance. Thus, diagnostic techniques able to early detect and monitor mitochondrial dysfunction have great relevance in terms of possible primary/secondary prevention measures and of therapies specifically targeting liver mitochondria [1,2,3].

2. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in the Liver

Mitochondrial dysfunction is one of the most distinctive characteristics of NAFLD

[1][68]. In NAFLD patients, increased plasma levels of FFA are firstly associated with increased intrahepatic inflow

[2][24] and early mitochondrial biogenesis through peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α (PGC1-α) activation. This step, in turn, leads to increased FFA oxidation rates and increased or unchanged mitochondrial function

[3][69]. Coupling of FFA oxidation to ATP generation might be dysfunctional already, because of emerging ultrastructural changes and increased expression of uncoupling proteins. With progression of NAFLD, however, mitochondrial ATP generation is further impaired resulting in defective cellular energy charge

[4][5][6][7][70,71,72,73]. The precise pathways governing such changes of mitochondrial performance are still unknown.

The increased accumulation of FA in the hepatocytes (neutral lipid droplets) during insulin-resistance-associated NAFLD, which is pathologically defined as hepatic steatosis, lead to a series of mitochondrial alterations ranging between mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) damage to sirtuin alteration. The mtDNA, a circular double-stranded molecule located in the mitochondrial matrix, encodes about the 10% of mitochondrial proteins, the others being encoded by the nuclear DNA. mtDNA encodes proteins necessary for the assembly and activity of mitochondrial respiratory complexes

[8][74]. Ongoing oxidative stress during steatosis can severely impair mtDNA function

[9][5] with further amplification of oxidative stress, mitochondrial biogenesis, and ultimately NAFLD severity and inflammation

[10][11][12][13][75,76,77,78].

Alteration of the mitochondrial function compromises also the prooxidant/antioxidant balance, with an increase in non-metabolized fatty acids (FA) in the cytosol as a consequence of the blockade of FFA β-oxidation and the resulting stimulation of ROS production

[14][15][79,80]. Mitochondrial dysfunctions are often accompanied by considerable ultrastructural changes such as megamitochondria, loss of cristae, and formation of paracrystalline inclusion bodies in the organelle matrix

[16][81].

In addition, in NAFLD, the excessive accumulation of lipotoxic lipids in the hepatocyte generates a dysfunctional electron transfer chain with generation of abnormal levels of ROS via involvement of glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GPDH), α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (AKGDH), and pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH). Besides, the excessive accumulation of FFA into mitochondria, subsequent to an increased uptake or an insulin-resistance situation, may elicit an increase of the inner mitochondrial membrane permeability. Mitochondrial cytochrome P450 2E1 (CYP2E1), a potential direct source of ROS, has been shown to have an increased activity in a rodent model of NASH as well as in NASH patients

[17][18][82,83]. CYP2E1, a cytochrome responsible for long-chain fatty acid metabolism, produces oxidative radicals and could also act as a part of the “second hit” of the pathophysiological mechanism of NAFLD

[19][84]. In addition to the pro-oxidant mechanism, a decreased activity of several detoxifying enzymes was seen using an experimental model of NASH. Glutathione peroxidase (GPx) activity is reduced likely due to GSH depletion and impaired transport of cytosolic GSH into the mitochondrial matrix

[20][85]. The initial mitochondrial dysfunction can be further exacerbated by the production of mtDNA mutation by ROS and highly reactive aldehydes, such as malondialdehyde (MDA) and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (4-HNE), through lipid peroxidation following the interaction between ROS and PUFA. Cytochrome C oxidase may be directly blocked by MDA while 4-HNE may contribute to “electron leakage” uncoupling complex 2 of the ECT whose oxidative capacity may be also diminished by derivative damage by interaction between mitochondrial membranes and both MDA and 4-HNE

[21][86].

Aquaporin-8 (AQP8), a pleiotropic aquaporin channel

[22][23][24][87,88,89] allowing movement of hydrogen peroxide in addition to water and ammonia, localized at multiple subcellular levels in hepatocytes

[25][90], is also present in mitochondria, where it has been suggested to facilitate the release of hydrogen peroxide across the inner mitochondrial membrane following ROS production

[26][91].

Mitochondrial redox imbalance and high Ca

2+ uptake have been shown to induce the opening of the permeability transition pore (PTP) with consequent disruption of energy-linked mitochondrial functions and triggering of cell death in many disease states including non-alcoholic fatty liver disorders

[27][92].

In previous studies, we used the rat model of a choline-deprived diet for 30 days inducing simple liver steatosis. In particular, peroxidation of the membrane lipid components participates in mechanisms of oxygen-free radical toxicity

[28][93]. Cardiolipin is a phospholipid localized almost exclusively within the inner mitochondrial membrane close complexes I and III of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Notably, cardiolipin becomes an early target of oxygen-free radical attack, a step leading to deranged mitochondrial bioenergetics. In a first study, we assessed various parameters related to mitochondrial function such as complex I activity, oxygen consumption, reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and cardiolipin content and oxidation. Complex I decreased by 35% in mitochondria isolated from steatotic livers, compared with the controls, and changes were associated with parallel changes in state 3 respiration. At the same time, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) generation increased significantly in mitochondria. The mitochondrial content of cardiolipin, a phospholipid required for optimal activity of complex I, decreased by 38% in parallel with an increase in the level of peroxidised cardiolipin. Data confirm that dietary steatosis induces mitochondrial dysfunction revealed by deranged complex I function attributed to ROS-induced cardiolipin oxidation and function

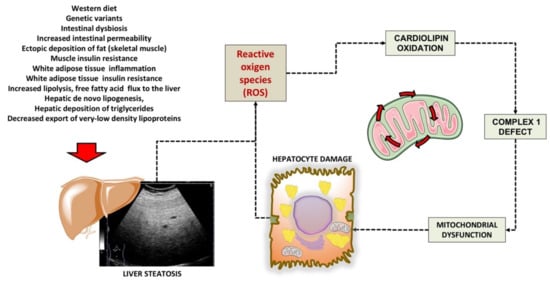

[29][94]. A putative scenario of damage is depicted in

Figure 1.

Figure 1. Putative mechanisms of damage involving cardiolipin in liver mitochondria during liver steatosis. Following several predisposing factors, liver steatosis develops. The increased production of ROS is associated with mitochondrial cardiolipin oxidation, defective complex 1, and furthers mitochondrial and hepatocyte dysfunction. Cardiolipin is a phospholipid localized almost exclusively within the inner mitochondrial membrane close to complexes I and III of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Mechanisms of damage have been elucidated in the study by Petrosillo et al., using the rodent model fed a choline-deficient diet to induce simple liver steatosis

[29][94].

In addition, using the choline-deficient steatogenic diet in the rat model, we measured the circulating and hepatic redox active and nitrogen-regulating molecules thioredoxin, glutathione, protein thiols (PSH), mixed disulphides (PSSG), NO metabolites nitrosothiols, nitrite plus nitrate (NOx), and lipid peroxides (TBARs). The histologically proven hepatocellular steatosis (75% of liver weight at day 30) was paralleled by increased serum and hepatic TBARs (r = 0.87,

p < 0.001) and lipid content (r = 0.90,

p < 0.001). Liver glutathione and thioredoxin 1 initially increased and then decreased, while, from Day 14, PSH decreased, and NO derivatives increased. Mitochondrial nitrosothiols were inversely related to thioredoxin 2. These results suggest that adipocytic transformation of hepatocytes is accompanied by major interrelated modifications of redox parameters and NO metabolism, especially at the mitochondrial level, suggesting an early adaptive protective response but also an increased predisposition towards pro-oxidant insults

[30][95].

The combination of these events explains how mitochondrial dysfunction becomes a key step paving the way to cells and organ damage. The main events in this scenario include the lack of energy supply by ATP and excessive generation of ROS. In case of prolonged starvation or diabetes, for example, ketone body synthesis occurs, when oxaloacetate is depleted due to its involvement in gluconeogenesis. In this scenario in the mitochondria, the acetyl-CoA does not enter the TCA cycle, and is converted to ketone bodies (i.e., acetone, acetoacetate, and β-hydroxybutyrate (β-HB)). Some metabolic markers might appear in the systemic circulation, for example with an abnormal acetoacetate/β-OH-butyrate ratio

[31][32][9,96], but they cannot be easily monitored and are rather unspecific. In type 2 diabetes mellitus and NAFLD, the hepatic mitochondrial metabolism is impaired

[33][34][97,98], associated with remodelling of mitochondrial lipids

[35][99], and increased mitochondrial mass and respiratory capacity

[36][100]. Lipotoxicity can influence acetyl-CoA metabolism

[37][101] with excessive turnover of the tricarboxylic acid cycle

[33][97]. In the steatogenic model of cultured hepatocytes, the combination of fructose and FFA caused profound effects on the lipogenic pathways. We noticed increased steatosis and reduced cell viability, increased apoptosis, oxidative stress and, mitochondrial respiration in the Seahorse system. Hepatic cell abnormalities can be prevented, and in this model, the damage improved by treating the cells with the nutraceutical silybin

[38][102].

Mitochondrial dysfunction is associated, in NASH, with the ongoing oxidative state of hepatocytes, and is able to affect intracellular signalling pathways by generation of DAMPs and to activate stellate cell

[39][103].

A recent in vitro study demonstrated that circulating factors contained in plasma samples from NAFLD patients were able to generate a NAFLD-like phenotype in isolated hepatocytes, with effects mediated by NLRP3-inflammasome pathways and by the activation of intracellular signalling related to SREBP-1c, PPAR-γ, NF-kB and NOX2

[40][104].

Besides external conditions affecting the metabolic homeostasis and mitochondrial function, genetically driven conditions can also lead to altered hepatic mitochondrial activity and peroxisomal β-oxidation

[41][42][43][105,106,107]. In particular, the membrane bound O-acyltransferase domain containing 7-trans-membrane channel-like 4 (MBOAT7-TMC4) is localized to the intracellular membranes of mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum, and lipid droplets. MBOAT7-TMC4 acts as lysophospholipid acyltransferase, and regulates the incorporation of arachidonic acid into phosphatidylinositol

[44][108]. This pathway, due to its key role, might be considered a promising therapeutic target. The expression of MBOAT7-TMC4 is decreased in the rs641738 polymorphism, and this leads to the onset of liver steatosis and to an altered liver histology

[45][46][109,110], to fibrosis in alcoholic liver disease

[47][111] and in chronic hepatitis C

[48][112]. In a mice model of NASH, the deletion of hepatocyte Mboat7 is linked to with increased fibrosis, with no effects on inflammation

[49][113]. Mboat7 also promotes the degradation of lysophosphatidylinositol, and the accumulation of this molecule in Mboat7 KO mice generates NASH

[50][114], also through the activation of the G-protein coupled receptor GPR55

[51][115]. Aging processes is associated with altered subcutaneous adipose tissue function, with mechanisms that involve a reduced mitochondrial activity

[52][53][116,117], the accumulation of senescent adipocytes, and impaired development of pre-adipocytes

[54][118]. Liver mitochondria also play a relevant role in lipid-induced hepatic insulin resistance, through mechanisms linking specific lipid metabolites and cellular compartments and leading to subcellular dysfunctions

[55][119]. In particular, the quantitative assessment of DAG stereoisomers (sn-1,2-DAGs, sn-2,3- DAGs, and sn-1,3-DAGs) and ceramides in the endoplasmic reticulum, mitochondria, plasma membrane, lipid droplets, and cytosol showed, using an antisense oligonucleotide, the onset of hepatic insulin resistance in rats, which was associated with the acute liver-specific knockdown of diacylglycerol acyltransferase-2. The dysregulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma co-activator-1α (PGC-1α) contributes to the pathogenesis and to the sequence of NASH-HCC, with metabolic pathways involving gluconeogenesis, fatty acid oxidation, antioxidant response, DNL, and mitochondrial biogenesis

[56][120].

Experimental data indicate that mitochondrial dysfunction is also a specific target for toxic chemicals of environmental origin mainly introduced bycontaminated food and water and leading to NAFLD.

A recent study in 2446 young adults showed that toenail cadmium concentration, a marker of long-term exposure, was associated with higher odds of prevalent NAFLD independently from race, sex, BMI or smoking status

[57][121]. In a mouse model of chronic cadmium exposure, hepatic Cd concentrations ranging from 0.95 to 6.04 μg/g wet weight were able to induce, following a 20-week exposure, NAFLD and NASH like phenotypes linked with mitochondrial dysfunction, fatty acid oxidation deficiency and a significant suppression of sirtuin 1 signalling pathway

[58][122]. Epidemiologic studies point to a positive association between arsenic exposure (i.e., urinary arsenic concentrations) and risk of NAFLD

[59][123]. This evidence is paralleled by experimental findings showing, in isolated rat liver mitochondria exposed to arsenic, a marked decrease in total mitochondrial dehydrogenase activity with increased ROS generation, MMP, and MDA levels, and decreased activity of mitochondrial catalase and GSH

[60][124].

In a cohort of 6389 adolescents from the NHANES survey, blood mercury levels were linked with the risk of NAFLD, with the most evident association in underweight or normal weight subjects

[61][125]. In a recent animal model, exposure to methylmercury during 12 weeks induced mitochondrial swelling, ROS overproduction, increased gluthatione oxidation, and reduced protein thiol content

[62][126].

Similar pathways linking environmental pollution with NAFLD in terms of both epidemiologic findings of increased NAFLD risk and animal/in vitro evidence of mitochondrial dysfunction also have been shown in the case of air pollution

[63][64][65][127,128,129], endocrine disrupting chemicals

[63][64][65][66][67][127,128,129,130,131], and pesticides

[68][69][70][71][132,133,134,135].

There are few ways to investigate mitochondrial metabolic processes, i.e., using isolated organelles, mitochondrial fractions, and cell culture

[72][136]. Few studies explored the impaired mitochondrial function in NAFLD. Protocols investigating the effects of xenobiotics and drugs on mitochondrial function can provide some information

[73][74][137,138]. Metabolomics can also explore specific mitochondrial functions

[75][139] by studying genetic perturbations

[76][140]. The measure of circulating mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is another biomarker of mitochondrial dysfunction. Changes to liver mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) can precede mitochondrial dysfunction and irreversible liver damage. Malik et al.

[77][141] by using a rodent dietary approach, demonstrated that a high-fat or a high-fat/high-sugar diet for 16 weeks was associated with fast alterations in mtDNA. Thus, dietary changes in liver mtDNA can occur in a relatively short time. Mouse liver contained a high mtDNA content (3617 +/− 233 copies per cell), which significantly increased when the mice were fed an HFD diet. This increase, however, was not functional; i.e., it was not translated into an increased expression of mitochondrial proteins. Furthermore, liver dysfunction was accelerated alongside the downregulation of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) and mtDNA replication machinery as well as upregulation of the mtDNA-induced inflammatory pathways.