Serendipity is defined as the ability to recognize and evaluate unexpected information and generate unintended value from it. Based on this definition, Napier and Vuong propose a framework to develop the notion of serendipity as a strategic advantage (or competitive advantage), both in practice and in research.

- serendipity

- creativity

- strategic advantage

- business management

- innovation

- serendipity process

Introduction

Since the term “serendipity” was coined in the fairy tale of The Three Princes of Serendip [1], serendipity has been discussed in many subjects, like science [2], business [3], education [4], career choice [5], etc. The concept is referred to various things, such as chance, coincidence, destiny, fate, karma, kismet, luck, and providence [5][6]. However, they have three similar main characteristics:

- Serendipity derives from unsought, unexpected, unanticipated, and unintentional events or information [7];

- The information or event is out-of-the-ordinary, anomalous, surprising, and inconsistent with existing thoughts, findings, or theories [8];

- The individual has to have the capacity and capability to recognize and capitalize the unexpected and anomalous events or information for solving a problem or finding an opportunity [9].

While the first two characteristics focus on the unexpectedness and anomalousness of the information, which are hard to control and manage, the third characteristic suggests that serendipity only happens when the individual has the ability to recognize and evaluate unexpected information and generate unintended value from that. The serendipity gained and lost in the case of the floppy-eared rabbits is a prime example of the third characteristic [2].

As serendipity significantly relies on the alertness and capability of an individual to happen [7][10][11][12], scholars believe that the possibility of encountering serendipity can be enhanced by developing appropriate organization’s cultural and physical infrastructures as well as individuals’ skills and capabilities. Grounded on this belief, Napier and Vuong [13] proposed a framework for developing the notion of serendipity as a strategic advantage (or competitive advantage). Even though the framework was constructed mostly based on examples from the business perspective, it can be still applied as a general framework for other aspects, like science, education, politics, etc.

'Serendipity as a strategic advantage' framework

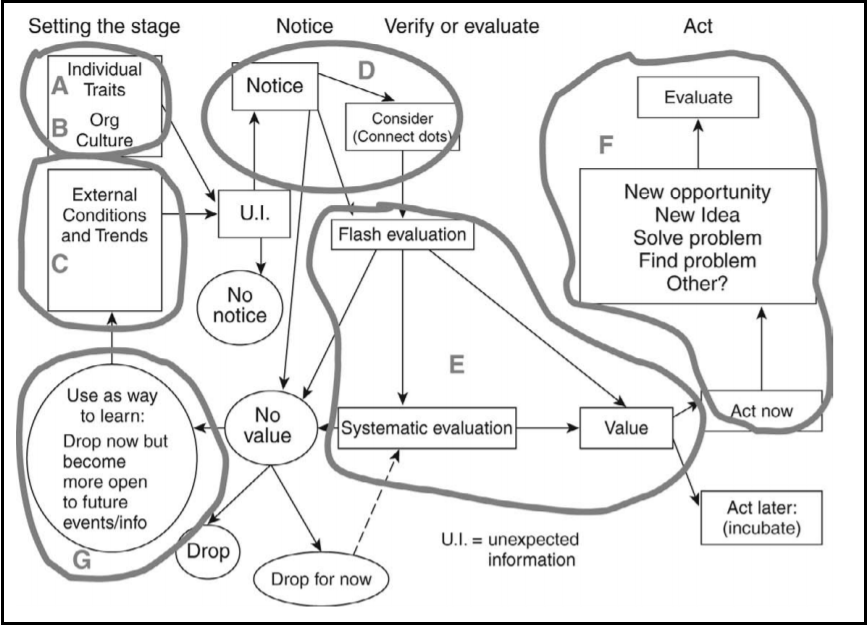

The framework that Napier and Vuong [13] proposed to develop the conception of serendipity as a strategic advantage consists of four main stages, with subparts in some (see Figure 1). The four main stages are as follows:

- Setting the stage

- Noticing unexpected information

- Evaluating the information

- Taking action upon the information

1. Setting the stage

The first stage is setting the stage or conditions that can improve the individual’s likelihood to notice unexpected information or events. This stage includes subparts ‘A’, ‘B’, ‘C’, and ‘G’, which correspond to factors that can influence the likelihood of unexpected information being noticed. ‘A’ is the traits or conditions of an individual that will make them more or less likely to notice unsought and out-of-ordinary information, such as openness, confidence, curiosity, and alertness. ‘B’ is the organizational culture that can affect serendipity’s appearance likelihood, like openness to new ideas, allowance for “sloppiness,” a cross-discipline mix of people, etc.

External conditions and trends represented by ‘C’ indicate the situations happening outside of the organization. These conditions and trends can be crucial determinants of serendipity’s appearance likelihood in specific settings or industries. ‘G’ is quite special. Although some information is evaluated as “no value,” the simple act of noticing and recognizing possibilities may enhance the openness for setting the stage for future noticing.

2. Noticing unexpected information

The second stage (or ‘D’) of the serendipity process has two main functions. The first function is noticing or being alert to unexpected information. The second function is connecting unexpected information. Connecting unexpected information can provide more valuable inputs preceding the evaluation stage than not connected information, though the second function is not always necessary.

3. Evaluating the information

After the information is noticed or connected, flash evaluation and systematic evaluation (or ‘E’) will be subsequently carried out for assessing the values of the unexpected information. Initially, an individual does a quick, almost gut feeling assessment of the unusual information. That assessment makes the individual become more alert to whether there are ways to connect the observed information to other already known information, both in internal sources (e.g. personal or organizational sources) and external sources (e.g. environmental sources).

Suppose the flash evaluation cannot assess the unexpected information. In that case, it will be assessed by a more systematic evaluation which includes an analytical assessment that leads to a clearer verification of the information’s potential value. During this process, the evaluation might be affected by the risk tolerance, uncertainty surrounding the information and evaluation, timing, and finding additional information, which will help the individual confirm or dispute the initial unexpected information.

Napier and Vuong also suggest that there are three critical elements in the systematic evaluation part: (1) the distance between perceived (or anticipated) opportunity from the unexpected information and the reliability of the evaluation of the unexpected information (in the middle), (2) the general evaluation process from “gut feel” to a firmer belief about the evaluation, and (3) the factors that may influence the process of evaluation. Those elements also determine the extent to which the information used in making decisions is weighted internally or externally

The systematic evaluation can result in three decision outcomes that lead to different levels of competitive advantages. First, when the evaluator/decision-makers are not “swayed” too strongly by any internal or external factors, the evaluation is “balanced”, and the outcome may well be an opportunity that the decision-maker leverages when competitors do not.

Second, the decision-maker notices unexpected information but mostly because others point it out and suggest a way to leverage it. The decision-maker then essentially follows the herd to try and take advantage of the unusual information, resulting in what might be called a “herd” outcome. In this case, there is no competitive advantage to the organization because a herd of organizations is trying to leverage the information.

Third, internal decision-makers may be pressured by external sources, such as government policymakers, to act. In this case, the organization may act on unexpected information without thoroughly considering external factors or repercussions. External sources evaluated unexpected information for the internal decision-makers, and the subsequent outcome was not necessarily in the favor of decision-makers.

Figure 1: ‘Serendipity as a strategic advantage’ framework. Retrieved and modified from Napier and Vuong.

4. Taking action upon the information

To become a competitive advantage, the assessment must yield value and action because the ability to recognize and evaluate unexpected information has no value in itself. Whether the individuals and the organization as a whole can leverage the use of serendipity to create value will determine the results of solving an existing or not-yet-tackled problem, finding an opportunity, or generating new ideas for future use.

Applications

The ‘serendipity as a strategic advantage’ framework has an important contribution to the science of serendipity. Sethna [14] suggests that using serendipity as a strategic advantage is one of the most prominent definitions of serendipity, besides chance, fate, destiny, karma, etc. Indeed, several frameworks and models have been built upon the serendipity process indicated by the ‘serendipity as a strategic advantage’ framework. Those frameworks and models include the 3D information process of creativity [3], the mindsponge mechanism [15], the digital information encountering model [16], and the 4S model (strategy, serendipity, storytelling, and software) in entrepreneurial marketing [17].

Moreover, the notion of serendipity in the framework has also been employed for discussing how to improve creativity or the chance to encounter serendipity in various aspects, such as teaching and training [18][19], doctoral education [20], new ventures’ performance and success [21][22], computational entrepreneurship [23], business spin-offs [24], land use policy [25], scientific thinking [26], corporate sector’s innovation [27][28], and scholarly publishing [29][30].

References

- Merton RK, Barber E. (2011). The travels and adventures of serendipity. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Barber B, Fox RC. (1958). The case of the floppy-eared rabbits: An instance of serendipity gained and serendipity lost. American Journal of Sociology, 64(2), 128-136. https://doi.org/10.1086/222420

- Vuong QH, Napier NK. (2014). Making creativity: the value of multiple filters in the innovation process. International Journal of Transitions and Innovation Systems, 3(4), 294-327. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTIS.2014.068306

- Delcourt MA. (2003). Five ingredients for success: Two case studies of advocacy at the state level. Gifted Child Quarterly, 47(1), 26-37. https://doi.org/10.1177/001698620304700104

- Betsworth DG, Hansen JIC. (1996). The categorization of serendipitous career development events. Journal of Career Assessment, 4(1), 91-98. https://doi.org/10.1177/106907279600400106

- Eyre RM. (1997). Spiritual Serendipity: Cultivating and Celebrating the Art of the Unexpected. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Cunha MPE, Clegg SR, Mendonça S. (2010). On serendipity and organizing. European Management Journal, 28(5), 319-330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2010.07.001

- van Andel P, Bourcier D. (2002). Serendipity and abduction in proofs, presumptions and emerging laws. In M Mac & C Tillers (Eds.), The Dynamics of Judicial Proof (pp. 273-286). New York: Springer.

- De Rond M. (2014). The structure of serendipity. Culture and Organization, 20(5), 342-358.

- Diaz de Chumaceiro CL. (2004). Serendipity and pseudoserendipity in career paths of successful women: Orchestra conductors. Creativity Research Journal, 16(2-3), 345-356. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2004.9651464

- Gaglio CM, Katz JA. (2001). The psychological basis of opportunity identification: Entrepreneurial alertness. Small Business Economics, 16(2), 95-111. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011132102464

- Williams EN, Soeprapto E, Like K, Touradji P, Hess S, Hill CE. (1998). Perceptions of serendipity: Career paths of prominent academic women in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 45(4), 379. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.45.4.379

- Napier NK, Vuong QH. (2013). Serendipity as a strategic advantage? In T Wilkinson & VR Kannan (Eds.), Strategic Management in the 21st Century (Vol. 1). Santa Barbara, California: Praeger.

- Sethna Z. (2017). New perspectives on digital marketing, social entrepreneurship and serendipity in entrepreneurial marketing. Journal of Research in Marketing and Entrepreneurship. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRME-11-2017-0048

- Vuong, QH, Napier NK. (2015). Acculturation and global mindsponge: an emerging market perspective. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 49, 354-367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2015.06.003

- https://asistdl.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/pra2.2017.14505401031

- Nightingale K, Sethna Z. (2020). Entrepreneurial marketing and the 4S model: strategy, serendipity, storytelling, software. In I Fillis & N Telford (Eds.), Handbook of Entrepreneurship and Marketing (pp. 238–261). Glos & Massachusetts: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Guimarães SM. (2017). Estilos de pensamento, atos de currículo e currículo em atos na formação em educação física. (Doctoral degree), Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Repositório Institucional da UFSC. Retrieved from https://repositorio.ufsc.br/handle/123456789/189912

- Papaleontiou-Louca E, Varnava-Marouchou D, Mihai S, Konis E. (2014). Teaching for creativity in universities. Journal of Education and Human Development, 3(4), 131-154. http://dx.doi.org/10.15640/jehd.v3n4a13

- McCulloch A. (2021). Serendipity in doctoral education: the importance of chance and the prepared mind in the PhD. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2021.1905157

- Fultz AE, Hmieleski KM. (2021). The art of discovering and exploiting unexpected opportunities: The roles of organizational improvisation and serendipity in new venture performance. Journal of Business Venturing, 36(4), 106121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2021.106121

- Turner M, Pech R. (2020). Serendipitous lightning: an entrepreneurial case study from Mongolia. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 13(2), 196-212. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEEE-03-2020-0054

- Vuong QH. (2019). Computational entrepreneurship: From economic complexities to interdisciplinary research. Problems Perspectives in Management, 17(1), 117-129. http://dx.doi.org/10.21511/ppm.17(1).2019.11

- Royer A. (2017). Spin-offs d’entreprises, une modalité d’innovation accélératrice de création de valeur. Retrieved from https://philarchive.org/archive/ROYSDU

- De Rosa M, McElwee G, Smith R. (2019). Farm diversification strategies in response to rural policy: A case from rural Italy. Land Use Policy, 81, 291-301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.11.006

- Ruisel I. (2016). Psychológia Vedy A Vedeckého Myslenia: Ústav experimentálnej psychológie & Centrum spoločenských a psychologických vied SAV. Retrieved from https://psychologia.sav.sk/upload/veda.pdf

- Vuong QH, Napier NK. (2014). Resource curse or destructive creation in transition: Evidence from Vietnam's corporate sector. Management Research Review, 37(7), 642-657. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-12-2012-0265

- Vuong QH, Napier NK, Samson DE. (2013). Innovation as determining factor of post-M&A performance: The case of Vietnam. International Journal of Business and Management, 8(18), 25-31. http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ijbm.v8n18p25

- Vuong QH. (2020). Plan S, self‐publishing, and addressing unreasonable risks of society publishing. Learned Publishing, 33(1), 64-68. https://doi.org/10.1002/leap.1274

- Vuong QH, Ho MT. (2020). Rethinking editorial management and productivity in the COVID-19 pandemic. European Science Editing, 46, e56541. https://doi.org/10.3897/ese.2020.e56541

- Vuong QH, Ho MT. (2020). Rethinking editorial management and productivity in the COVID-19 pandemic. European Science Editing, 46, e56541. https://doi.org/10.3897/ese.2020.e56541