Amidst a contemporary culture of climate awareness, unprecedented levels of transparency and visibility are dictating industrial organizations to broaden their value chains and deepen the impacts of CSR initiatives. While it may be common knowledge that the 2030 agenda cannot be achieved on a business-as-usual trajectory, this study seeks to determine to what ends the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have impacted Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) research. Highlighting linkages and interdependencies between the SDGs and evolution of CSR practice, this paper analyzes a final sample of 56 relevant journal articles between 2015-2020. With the intent to bridge policy and practice, thematic coding analysis supported the identification and interpretation of key emergent research themes. Using three descriptive categorical classifications (i.e. single-dimension, bi-combination of dimensions, sustainability dimension), the results of this paper provide an in-depth discussion into strategic community, company, consumer, investor, and employee foci. Also, the analysis provides a timely and descriptive overview of how CSR research has approached the SDGs and which are being prioritized. By deepening the understanding of potential synergies between business strategy, global climate agendas, and the common good, this paper contributes to an increased comprehension of how CSR and financial performance can be improved over the long-term.

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- CSR

- Sustainability

- Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

1. Definition

The work of Freeman et al. (2010) and Werther and Chandler (2010) underscore that today’s business paradigm requires at minimum, CSR activities maintain a strategic (i.e. action-oriented, solutions-focused) and stakeholder orientation (i.e. boundary spanning perspective) to creating shared value. Inherent to this definition is a transition away from philanthropic add-on logic towards its incorporation as a core pillar to managerial decision-making. Based on the results of this review, the authors identify that CSR in the advent of the SDGs must also: manage diverse interests to achieve a holistic 4-D model to sustainable development (i.e. economic, social, environmental, and cultural); balances paradox logic to issues of sustainability (i.e. balancing short-term returns while maintaining the long-term vision of sustainable development); and acknowledge an embedded view of the business-society-nature interface (i.e. unbalanced scorecard impact assessments to prioritize nature and societal outcomes over business).

The work of Freeman et al. (2010) and Werther and Chandler (2010) underscore that today’s business paradigm requires at minimum, CSR activities maintain a strategic (i.e. action-oriented, solutions-focused) and stakeholder orientation (i.e. boundary spanning perspective) to creating shared value. Inherent to this definition is a transition away from philanthropic add-on logic towards its incorporation as a core pillar to managerial decision-making. Based on the results of this review, the authors identify that CSR in the advent of the SDGs must also: manage diverse interests to achieve a holistic 4-D model to sustainable development (i.e. economic, social, environmental, and cultural); balances paradox logic to issues of sustainability (i.e. balancing short-term returns while maintaining the long-term vision of sustainable development); and acknowledge an embedded view of the business-society-nature interface (i.e. unbalanced scorecard impact assessments to prioritize nature and societal outcomes over business).

Both a process and outcome in-of-itself, a contemporary definition of CSR in the SDGs era denotes “the integration of a holistic perspective across all levels of a firm’s strategic planning and decision-making so that the firm is managed knowledgeably in the interests of a broad set of stakeholders, spanning beyond firm boundaries, to achieve maximum shared value over the medium to long-term while providing sufficient short-term returns to warrant continued investment, iteration, and innovation necessary for business, society, and nature to thrive”.

2. Introduction

Both a process and outcome in-of-itself, a contemporary definition of CSR in the SDGs era denotes “the integration of a holistic perspective across all levels of a firm’s strategic planning and decision-making so that the firm is managed knowledgeably in the interests of a broad set of stakeholders, spanning beyond firm boundaries, to achieve maximum shared value over the medium to long-term while providing sufficient short-term returns to warrant continued investment, iteration, and innovation necessary for business, society, and nature to thrive”.

2. Introduction

In a paradigm characterized by unprecedented levels of transparency and visibility, public stakeholders and disclosure standards have gained considerable power in their ability to drive trends toward more sustainable business practices. Amidst the advent of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), global sustainability discourse has progressed to a point where it is inseparable from the role of the firm [1]. What must be considered a keystone element of progressive competitive strategies, creating shared value for the common good has become integral to Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) in a way that changes the narrative on ‘what’ constitutes CSR and ‘how’ companies approach it in practice [2]. Under cognitive framings of managerial decision-making, past CSR behavior(s) and associated performance implications have been shown to strongly influence the perceptions of leadership regarding the relevance of social and environmental issues in value creation [3]. Conceptualized under ethical motives for societal well-being, the proliferation of business case(s) for CSR now materializes as a fiduciary duty and the sustainability case of business [4]. As the concept of CSR evolves, it is critical to understand how the SDGs and sustainability more broadly are influencing corporate strategy, CSR agendas, reporting practices, disclosure mechanisms, stakeholder expectations, and regulatory requirements.

The motivations for investing in CSR initiatives and integrating them into business strategy are grounded in a shared desire to ensure a firm’s long-term success and survival [5]. By aligning the purpose and values of CSR with market drivers and stakeholder demands, CSR practices have become due diligence for preserving the firm’s license to operate, avoiding reputational damages, building loyalty, and maintaining competitive positioning [6]. Empirically grounded, the impacts of CSR on financial performance can be explained through top-line growth [7], decreased cost to capital, increased reputation and goodwill [8], and reduced technical and material risks [9].The motivations for investing in CSR initiatives and integrating them into business strategy are grounded in a shared desire to ensure a firm’s long-term success and survival [5]. By aligning the purpose and values of CSR with market drivers and stakeholder demands, CSR practices have become due diligence for preserving the firm’s license to operate, avoiding reputational damages, building loyalty, and maintaining competitive positioning [6]. Empirically grounded, the impacts of CSR on financial performance can be explained through top-line growth [7], decreased cost to capital, increased reputation and goodwill [8], and reduced technical and material risks [9].

Further, recent studies have shown that firms with well-coordinated and self-organized CSR strategies outperform their counterparts across similar industry groupings [10][11]. Superior share price performance has also been exhibited by companies listed on sustainability indices (i.e.,

Further, recent studies have shown that firms with well-coordinated and self-organized CSR strategies outperform their counterparts across similar industry groupings [10,11]. Superior share price performance has also been exhibited by companies listed on sustainability indices (i.e.,Dow Jones Sustainability Index

,FTSE4Good

) when compared to companies listed in their non-sustainable counterparts [12]. While a notable rise in the number of companies publishing CSR reports can be observed, the quality and consistency of content being disclosed vary significantly [13]. This becomes further compounded by the heterogeneity amongst global reporting standards and a divergence in rating(s) criteria. According to Berg et al. (2019), this is what can be referred to as “aggregate confusion

” [14]. Even with nearly 1400 companies, spanning 160 countries operating as signatories to theUnited Nations Global Compact [15], the simple fact remains that companies are afforded an overly flexible disclosure process that reinforces issues of evaluation, comparability, and ultimately usefulness [16].

[15], the simple fact remains that companies are afforded an overly flexible disclosure process that reinforces issues of evaluation, comparability, and ultimately usefulness [16].Whether pursuing business cases of CSR is enough to satisfy global sustainable development remains subject to debate within and across academic disciplines. Often resting on

Whether pursuing business cases of CSR is enough to satisfy global sustainable development remains subject to debate within and across academic disciplines. Often resting ona priori organizational frameworks, the legitimacy of this logic falls short when sustainable development is reduced under neo-liberal economic rationality or economic performance leveraged with coincidental CSR contributions [17]. In practice, bottom-line implications are left vulnerable to capricious public opinions, senior management turnover, and quarterly financial cycles [18]. Deeply ingrained throughout conventional cost accounting and performance management is a utilitarian view that rewards manager’s and senior leadership when acting as self-seeking opportunistic individuals with the intent to maximize personal economic interests [19]. Materializing in the form of ‘greenwashing’, the reduction of CSR under win-win scenarios at the intersection of the triple bottom long constitutes a key managerial motivation for CSR and a conventional approach to building the business case [20]. Rather than an end in-of-itself, CSR activities are treated as philanthropic add-ons necessary for catering to current public opinion while securing loyalty [17][21]. This does little in the way of transforming organizational behaviour in a manner that is required to support meaningful progress on the SDGs. This underscores the fact that the very notion of ‘doing well by doing good’ is fundamentally a proposition of diminishing returns [22][23].

organizational frameworks, the legitimacy of this logic falls short when sustainable development is reduced under neo-liberal economic rationality or economic performance leveraged with coincidental CSR contributions [17]. In practice, bottom-line implications are left vulnerable to capricious public opinions, senior management turnover, and quarterly financial cycles [18]. Deeply ingrained throughout conventional cost accounting and performance management is a utilitarian view that rewards manager’s and senior leadership when acting as self-seeking opportunistic individuals with the intent to maximize personal economic interests [19]. Materializing in the form of ‘greenwashing’, the reduction of CSR under win-win scenarios at the intersection of the triple bottom long constitutes a key managerial motivation for CSR and a conventional approach to building the business case [20]. Rather than an end in-of-itself, CSR activities are treated as philanthropic add-ons necessary for catering to current public opinion while securing loyalty [17,21]. This does little in the way of transforming organizational behaviour in a manner that is required to support meaningful progress on the SDGs. This underscores the fact that the very notion of ‘doing well by doing good’ is fundamentally a proposition of diminishing returns [22,23].Demonstrable of a lack of managerial know-how and information for intervention selection/design, research indicates that such realities negatively mediate management’s motivation/commitment to CSR [12]. Until this rationale is addressed systematically, strategic CSR literature will continue to turn out isolated success stories. As identified by Schaltegger et al. (2012), this will require that the formulation and implementation of strategy moves away from those that only strive for market sustainability through competitive advantages in the sense of the Resource-Based View (RBV) of the firm. By aligning the purpose and values of CSR with market drivers and stakeholder demands, CSR practices have become due diligence for preserving the firm’s license to operate, avoiding reputational damages, building loyalty, and maintaining competitive positioning [9]. Empirically grounded, the impacts of CSR on financial performance can be explained through top-line growth [7], decreased cost to capital, increased reputation and goodwill [8], and reduced technical and material risks [9].

With respect to research, Bansal and Song [24] highlight the fact that, despite novel insights being made on the role of the firm and its embeddedness within the business-society-nature interface, the variability among its subjective interpretations has limited construct validity in practice. Nevertheless, since the introduction of the SDGs, many firms have begun to strategically engage with the international framework as a means of creating functional linkages between performance outcomes and the common good [25]. An integrated framework comprised of 169 targets and 232 unique indicators, the SDGs have shifted CSR discourse from being reactive to stakeholders’ mandates to a proactive one that helps firms play an active role in influencing sustainable development trajectories [26].With respect to research, Bansal and Song [24] highlight the fact that, despite novel insights being made on the role of the firm and its embeddedness within the business-society-nature interface, the variability among its subjective interpretations has limited construct validity in practice. Nevertheless, since the introduction of the SDGs, many firms have begun to strategically engage with the international framework as a means of creating functional linkages between performance outcomes and the common good [25]. An integrated framework comprised of 169 targets and 232 unique indicators, the SDGs have shifted CSR discourse from being reactive to stakeholders’ mandates to a proactive one that helps firms play an active role in influencing sustainable development trajectories [26].

3. Research Findings and Results

3.1. Charting the Data

The studies were published in reputable journals such as the Journal of Cleaner Production, which has the highest number of published articles on the subject, followed by the Sustainability journal, and finally the European Journal of Sustainable Development. For the full list of published articles per journal, see Appendix A Table A1.

The studies were published in reputable journals such as the Journal of Cleaner Production, which has the highest number of published articles on the subject, followed by the Sustainability journal, and finally the European Journal of Sustainable Development. For the full list of published articles per journal, see Appendix A Table A1.3.1.1. Distribution of Studies Per Year

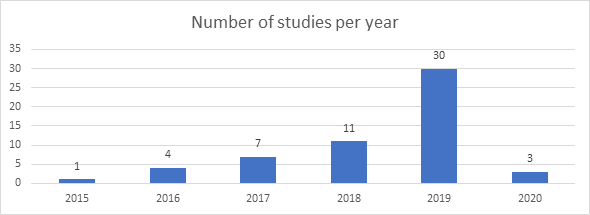

The analysis of this study shows that research on the topic of CSR and SDGs has increased substantially since 2015, with approximately 55% of the final sample being published in 2019 (see Figure 1). Given that the search protocol included articles published up to and including the end of January 2020, it is expected that the number of articles in 2020 is lower relative to previous years.

3.1.2. Distribution of Studies by Country

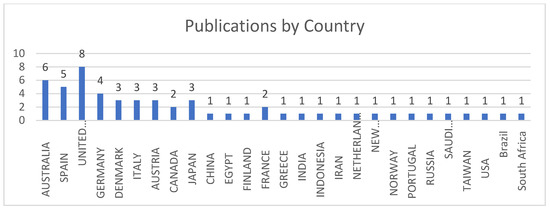

The final sample is geographically diverse, including articles published in both developed and developing countries. As shown in Figure 2, the United Kingdom had the highest number of published articles followed by Australia, Spain, and Germany. Out of the 56 articles we analyzed in this scoping review, 48 articles were published in developed countries, while 8 publications were from developing countries. The degree to which geographic clustering can be expected to exist is largely dependent on stakeholder awareness and availability of slack resources, which currently favors markets in developed countries [19]. Noteworthy topics for future comparative analyses might focus on assessing geographical disparities outlining ‘how’ and ‘why’ strategic CSR varies across contexts, and measuring the depth and degree to which firms can realize the benefits of CSR engagement in developed versus developing economies. While controlling for organizational and contextual influences, the United Nations’ SDGs framework should provide an internationally transferable measurement framework with 169 targets that might be translated and compared at the organizational level.

3.1.3. Distribution of Articles Based on SDG Focused

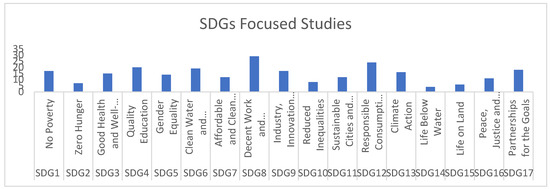

As shown in Figure 3, a large proportion of articles were conducted under a generic lens, linking corporate CSR activities with a general mention of progress towards the achievement of the SDGs. Relatively, a smaller cohort of articles adopted a narrowed lens connecting specific SDGs to CSR activities. The following section of this paper provides a thematic analysis of the 56 articles and highlights the main SDGs within the papers, which are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 3. Distribution of focused articles based on Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Distribution of focused articles based on Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).Table 1. Summary of Review Analysis.

| Source | Dimension | Strategic CSR | Research Focus | SDG(s) Covered |

|---|

| Naciti [27] | Naciti [70] | Socio-Environmental | ✔ | Company-focused | General |

| Poddar, Narula, and Zutshi [28] | Poddar, Narula, and Zutshi [76] | Sustainability | ✔ | Company-focused | General |

| Grzeda [29] | Grzeda [84] | Sustainability | × | Company-focused | General |

| Contreras, Bos, and Kleimeier [30] | Contreras, Bos, and Kleimeier [60] | Economic | × | Company-focused | General |

| Grover, Kar, and Ilavarasan [31] | Grover, Kar, and Ilavarasan [73] | Sustainability | ✔ | Company-focused | General |

| Calero, Garcia-Rodriguez De Guzman, Moraga, and Garcia [32] | Calero, Garcia-Rodriguez De Guzman, Moraga, and Garcia [86] | Sustainability | × | Company-focused | General |

| Cubilla-Montilla, Nieta-Librero, Galidno-Villardon, Vincente Galindo, and Garcia-Sanchez [33] | Cubilla-Montilla, Nieta-Librero, Galidno-Villardon, Vincente Galindo, and Garcia-Sanchez [57] | Social | × | Community-focused | General |

| Fasoulis and Kurt [34] | Fasoulis and Kurt [83] | Sustainability | ✔ | Company-focused | General |

| Buhmann, Jonsson, and Fisker [35] | Buhmann, Jonsson, and Fisker [62] | Socio-Economic | × | Company-focused | General |

| Perkiss, Dean, and Gibbons [36] | Perkiss, Dean, and Gibbons [87] | Sustainability | ✔ | Company-focused | General |

| Rosati and Fari [37] | Rosati and Fari [88] | Sustainability | ✔ | Company-focused | General |

| Barkemeyer and Miklian [38] | Barkemeyer and Miklian [85] | Socio-Economic | × | Company-focused | SDG: 1, 8, 9, 12, 13 |

| Medina-Munoz and Medina-Munoz [39] | Medina-Munoz and Medina-Munoz [53] | Social | × | Company-focused | General |

| Denoncourt [40] | Denoncourt [74] | Sustainability | ✔ | Company-focused | SDG 9 |

| Lu, Ren, Lin, He, and Streimikis [41] | Lu, Ren, Lin, He, and Streimikis [89] | Sustainability | × | Company-focused | General |

| Raj and Arun [42] | Raj and Arun [90] | Sustainability | ✔ | Company-focused | General |

| Cantele and Zardini [43] | Cantele and Zardini [51] | Sustainability | ✔ | Company-focused | General |

| Gunawan, Permatasari, and Tilt [44] | Gunawan, Permatasari, and Tilt [91] | Sustainability | ✔ | Company-focused | General |

| Gider and Hamm [45] | Gider and Hamm [68] | Socio-Economic | × | Consumer-focused | General |

| Sukhonos, Makarenko, Serpeninova, Drebot, and Okabe [46] | Sukhonos, Makarenko, Serpeninova, Drebot, and Okabe [92] | Sustainability | ✔ | Company-focused | General |

| Abdelhalim and Eldin [47] | Abdelhalim and Eldin [93] | Sustainability | ✔ | Company-focused | General |

| Munro and Arli [48] | Munro and Arli [94] | Sustainability | ✔ | Company-focused | General |

| Stahl, Brewster, Collings, and Hajro [49] | Stahl, Brewster, Collings, and Hajro [75] | Sustainability | ✔ | Company-focused | General |

| Liu [50] | Liu [95] | Sustainability | ✔ | Company-focused | General |

| Zavyalova, Studenikin, and Starikova [51] | Zavyalova, Studenikin, and Starikova [54] | Social | ✔ | Company-focused | SDGs 1,3,4,5,6,8,10 |

| Miralles-Quiros, Miralles-Quiros, and Nogueira [52] | Miralles-Quiros, Miralles-Quiros, and Nogueira [67] | Socio-Economic | × | Investor-focused | General |

| Avery and Hoope [53] | Avery and Hoope [61] | Economic | × | Company-focused | General |

| Rahdari, Sepasi, and Moradi [54] | Rahdari, Sepasi, and Moradi [64] | Socio-Economic | ✔ | Company-focused | General |

| Guandalini, Sun, and Zhou [55] | Guandalini, Sun, and Zhou [96] | Sustainability | × | Company-focused | General |

| Robinson, Martins, Solnet, and Baum [56] | Robinson, Martins, Solnet, and Baum [79] | Sustainability | × | Employee-focused | SDG 8 |

| Avrampou, Skouloudis, Iliopoulos, and Khan [57] | Avrampou, Skouloudis, Iliopoulos, and Khan [97] | Sustainability | × | Company-focused | SDGs 8, 10, 12 |

| Rosati and Faria [37] | Rosati and Faria [88] | Sustainability | ✔ | Company-focused | General |

| Zimmermann [58] | Zimmermann [98] | Sustainability | ✔ | Company-focused | General |

| Berning [59] | Berning [77] | Sustainability | × | Company-focused | SDG 3,4, 8, 9,10, 11, 12, 13 |

| Kim [60] | Kim [63] | Socio-Economic | × | Company-focused | General |

| Manas-Viniegra [61] | Manas-Viniegra [55] | Social | × | Company-focused | General |

| Bosch-Badia, Montllor-Serrats, and Tarrazon-Rodon [62] | Bosch-Badia, Montllor-Serrats, and Tarrazon-Rodon [81] | Sustainability | ✔ | Investor-focused | General |

| Calabrese, Costa, Ghiron, and Menichini [63] | Calabrese, Costa, Ghiron, and Menichini [66] | Socio-Economic | × | Employee-focused | SDG 5 |

| Yakovleva, Kotilainen, and Toivakka [64] | Yakovleva, Kotilainen, and Toivakka [99] | Sustainability | × | Company-focused | General |

| Ekiugbo and Papanagnou [65] | Ekiugbo and Papanagnou [100] | Sustainability | × | Company-focused | General |

| Wofford, MacDonald, and Rodehau [66] | Wofford, MacDonald, and Rodehau [80] | sustainability | ✔ | Employee-focused | SDG 17, 3, 8 |

| Kelly [67] | Kelly [56] | Social | ✔ | Community-focused | General |

| Scheyvens, Banks, and Hughes [68] | Scheyvens, Banks, and Hughes [101] | Sustainability | ✔ | Company-focused | General |

| Sharma [69] | Sharma [102] | Sustainability | ✔ | Company-focused | General |

| Banik and Lin [70] | Banik and Lin [103] | Sustainability | ✔ | Company-focused | SDG 8, 12 |

| Bull and Miklian [71] | Bull and Miklian [65] | Sustainability | ✔ | Company-focused | General |

| Soonsiripanichkul and Ngamcharoenmongkol [72] | Soonsiripanichkul and Ngamcharoenmongkol [69] | Socio-Economic | × | Consumer-focused | General |

| Nurunnabi, Esquer, Munguia, Zepeda, Perez and Velazquez [73] | Nurunnabi, Esquer, Munguia, Zepeda, Perez and Velazquez [72] | Economic-Environmental | × | Company-focused | SDG 7 |

| Selmier and Newenham-Kahindi [74] | Selmier and Newenham-Kahindi [104] | Sustainability | × | Company-focused | SDG 8,5,16 |

| Martinuzzi, Schonherr and Findler [75] | Martinuzzi, Schonherr and Findler [105] | Sustainability | ✔ | Company-focused | General |

| Ramboarisata and Gendron [76] | Ramboarisata and Gendron [58] | Social | × | Community-focused | General |

| Borges et al. [77] | Borges et al. [59] | Social | × | Community-focused | SDG 4 |

| Naidoo and Gasparatos [78] | Naidoo and Gasparatos [71] | Economic-Environmental | × | Company-focused | SDG 12 |

| Xia, Olanipekun, Chen, Xie, and Liu [79] | Xia, Olanipekun, Chen, Xie, and Liu [106] | Sustainability | ✔ | Company-focused | General |

| Katamba [80] | Katamba [82] | Sustainability | ✔ | Company-focused | SDG 3 |

| Annan-Diab and Molinari [81] | Annan-Diab and Molinari [78] | Sustainability | ✔ | Community-focused | General |

In line with findings of previous CSR research, the analysis of this study highlights the fact that there continues to be a hyper-emphasis on larger multi- and trans-national corporations in comparison to their small and medium enterprise counterparts [43].

3.2. Thematic Analysis

Using qualitative thematic coding methodology, a categorical framework for article classification was created. The content analysis approach was used to examine and assess the degree and nature of the influence of the SDGs on CSR literature. In this paper, the three categories of the sustainability dimensions framework by Alshehhi, Nobanee, and Khare [82] were adopted to analyze the distribution of the articles. The three categories are:

-

(1)Single-Dimension: Economic-Environmental-Social;

(1) -

Single-Dimension: Economic-Environmental-Social;

- (2)

-

Bi-Combination of dimensions: Socio-Economic, Economic-Environmental, and Social Environmental;

-

(2)Bi-Combination of dimensions: Socio-Economic, Economic-Environmental, and Social Environmental;

(3) -

(3)Sustainability Dimension.

-

Sustainability Dimension.

3.2.1. Theme 1: Single-Dimension

The review of this study found nine articles that highlight a single dimension of CSR, specifically the social (seven studies) and economic dimension (two studies). These articles speak specifically of the social dimensions of corporate actions that aim at increasing societal welfare. As part of this paradigm, the role of internal and external stakeholders, along with specific institutions, are highlighted with respect to their role in driving CSR agendas toward achieving the SDGs. Specific sub-themes of corporate social action and performance include corporate contributions toward poverty alleviation [39], solutions to social issues [51], corporate CSR volunteering [61], and corporate-civil society partnerships [67]. Articles examining societal influence in driving CSR focus on cultural values as a normative institutional pressure [33] and the role of responsible management education [76][77].

Articles focusing on the economic dimension of CSR address sustainable finance and investment while elaborating on the centrality of the business-case of sustainability as a vector for continued CSR engagement. This includes Contreras et al. [30], who explore the drivers of adopting voluntary sustainability regulations in financial institutions. In addition, Avery and Hooper [53] studied how corporate CEOs can change organizational culture and performance by investing in CSR. Of the nine articles focused on the economic dimensions of CSR, only two (i.e., Kelly [67] and Zavyalova et al. [51]) discuss corporate responsibility from a strategic lens that views CSR as a strategic planning process that can only be achieved through partnerships among concerned stakeholders. Most articles associated with this theme explore the SDGs from a holistic approach, that being a general focus on the framework rather than a specific reference to one or more goals. Two notable exceptions include Zavyalova et al. [51] and Borges et al. [77]. The former article examines business projects that are aimed at solving social sustainability issues that can help achieve “socially-oriented” SDGs, specifically SDG 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, and 10. The latter, Borges et al. [77], examine responsible management education hidden in the curriculum of business students with a focus on SDG 4, related to quality education.

3.2.2. Theme Two: Bi-Combination of Dimensions

The analysis highlights that some scholars tackle sustainability from a two-dimensional viewpoint, either (1) socio-economic, (2) socio-environmental, or (3) environmental-economic. In this review, eight articles examine CSR from a socio-economic dimension. In the first sub-category, namely the socio-economic dimension, the literature highlights the fact that organizations who invest in their CSR strategies should enhance their goodwill and develop trust from their stakeholders. Some authors adopted a corporate-oriented lens to reflect on the operationalization of CSR. For example, Buhmann et al. [35] explore how corporations can utilize their Human Resources (HR) towards achieving the SDGs. Likewise, Kim [60], Rahdari, Sepasi, and Moradi [54], and Bull and Miklian [71] analyze the socio-economic dimension of CSR from a corporate-driven standpoint, which highlights the positive economic and social gains for an organization to invest in CSR agendas. Calabrese, Costa, Ghiron, and Menichini [63] study the impact of gender equality on corporate governance, hence achieving robust CSR outcomes.

Nevertheless, some scholars focused on the socio-economic dimension of CSR from an outside-in approach, which targets external stakeholders such as investors [52] or customers [45][72]. The socio-economic articles all tackled the SDGs from a holistic perspective, except for Bull and Miklian [71], where the authors emphasize SDGs 1, 8, 12, and 13, which shed light on the economic and social implications of businesses.

Additionally, in the same category of the two-dimensional CSR strategies are the socio-environmental and the economic-environmental perspectives. In this review, only one article, that being Naciti [27], uses a socio-environmental lens to examine the role of an institution’s Board of Directors in achieving better sustainability performance with a higher prominence on the social and environmental pillars. The author uses a strategic CSR framework that highlights the long-term dimension of CSR, which necessitates strategic collaboration among concerned stakeholders. The author uses a company-focused viewpoint with a holistic overview of the 17 SDGs. Finally, the economic-environmental sub-category included two articles. The first, by Naidoo and Gasparatos [78], examines the sustainability drivers within CSR agendas as well as the performance measurement and reporting in corporations. This article focuses on SDG 12 and identifies best practices for responsible consumption and production in the SDGs era. Likewise, Nurunnabi et al. [73] analyze energy efficiency as a tool to achieve the SDGs with a specific focus on SDG 7.

3.2.3. Theme 3: Sustainability Dimension Studies

In the last categorization of this review, we identified articles that study CSR from a comprehensive viewpoint that covers the economic, social, and environmental dimensions of sustainability. Out of the 56 articles included in this scoping review, 36 articles analyzed CSR from a comprehensive approach that aims to balance the economic, social, and environmental pillars of sustainability. The majority of these articles (32 articles) have a company-focused approach, such as exploring the impact of CSR on company reputation [31], identifying products, and process innovation, within organizations towards achieving the SDGs [40]. The research on large organizations and multinationals still dominate the literature on CSR [28][49][59], with little emphasis on the role of small and medium enterprises in achieving the SDGs through their CSR agendas.

Moreover, some scholars in the sustainability dimension used a community-focused lens to highlight the needs of interdisciplinary education programs in the academic world and industry to help achieve the SDG via strategic CSR approaches [81]. Other scholars adopted an employee-focused lens that highlights the importance of decent working conditions for employees [56], especially gender issues in the workplace [66]. Finally, some used an investor-focused lens that explores the role of responsible investors in achieving the SDGs [62]. The majority of the articles in this theme (24 articles) covered SDGs in a generic sense. Yet, studies such as Denoncourt [40], Katamba [80], and Robinson et al. [56] tried to link specific goals with the CSR practices of companies such as SDGs 8, 12, and 13.

3.3. Summary of Scoping Review Results

3.3. Summary of Scoping Review Results

Table 1 summarizes the results of the scoping review. Although some single- and bi-dimensional articles exploring CSR from one- or two-dimension(s) view CSR as a strategic planning process, articles adopting a comprehensive approach to CSR are the main articles tackling CSR from a strategic lens such as Poddar, Narula, and Zutshi [28], Grover, Kar, and Ilavarasan [31], and Fasoulis and Kurt [34].

From a research-focussed perspective, the articles under review were classified according to whether their studies focused on companies or other internal or external stakeholders such as employees, consumers, investors, and the wider community. The analysis of this study shows that most articles that follow a comprehensive sustainability approach are company focused. A limited number of articles tackle sustainability from a stakeholder perspective, for example, Gider and Hamm [45], Miralles-Quiros, Miralles-Quiros, and Nogueira [52], and Wofford, MacDonald, and Rodehau [66].

Finally, the majority of the articles under study discuss CSR in relation to SDGs in a generic manner such as Naciti [27], Grzeda [29], and Buhmann, Jonsson, and Fisker [35]. On the other hand, some studies tackled specific SDGs in their studies. For instance, Denoncourt [40] examined the connection between CSR and SDG 9, “industry, innovation, and infrastructure”. Likewise, Calabrese, Costa, Ghiron, and Menichini [63] specifically studied the presence of SDG 5, “gender equality” among CSR managers. Other articles, however, mentioned more than one SDG in their studies. For instance, Barkemeyer and Miklian [38] explored the implications of their results on more than one SDG, and Zavyalova, Studenikin, and Starikova [51] attempted to frame the CSR initiatives of a leading multinational company under the umbrella of a number of SDGs. Overall, this review opens various potential avenues for new research in the business-society field specifically, and in the sustainable development discipline in general. Future research recommendations are discussed in the following section.

References

- Cantele, S.; Zardini, A. What drives small and medium enterprises towards sustainability? Role of interactions between pressures, barriers, and benefits. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 27, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshehhi, A.; Nobanee, H.; Khare, N. The Impact of Sustainability Practices on Corporate Financial Performance: Literature Trends and Future Research Potential. Sustainability 2018, 10, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Muñoz, R.D.; Medina-Muñoz, D.R. Corporate social responsibility for poverty alleviation: An integrated research framework. Bus. Ethic A Eur. Rev. 2019, 29, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavyalova, E.; Studenikin, N.; Starikova, E. Business participation in implementation of socially oriented sustainable development goals in countries of central asia and the caucasus region. Cent. Asia Caucasus 2018, 19, 56–63. [Google Scholar]

- Mañas-Viniegra, L. Corporate Volunteering within Social Responsibility Strategies of IBEX 35 Companies. RETOS. Revista de Ciencias de la Administración y Economía 2018, 8, 19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, I. Is the Time Right for Human Rights NGOs to Collaborate with Businesses that Want to Stop Dabbling with ‘Corporate Social Responsibility’ and Start Making Social Impact? J. Hum. Rights Pr. 2016, 8, 422–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubilla-Montilla, M.I.; Nieto-Libreros, A.B.; Galindo-Villardón, M.P.; Galindo, M.P.V.; García-Sánchez, I.-M. Are cultural values sufficient to improve stakeholder engagement human and labour rights issues? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 938–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramboarisata, L.; Gendron, C. Beyond moral righteousness: The challenges of non-utilitarian ethics, CSR, and sustainability education. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2019, 17, 100321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, J.C.; Ferreira, T.C.; De Oliveira, M.S.B.; Macini, N.; Caldana, A.C.F. Hidden curriculum in student organizations: Learning, practice, socialization and responsible management in a business school. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2017, 15, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, G.; Bos, J.W.; Kleimeier, S. Self-regulation in sustainable finance: The adoption of the Equator Principles. World Dev. 2019, 122, 306–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, G.; Hooper, N. How David Cooke implemented corporate social responsibility at Konica Minolta Australia. Strat. Leadersh. 2017, 45, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhmann, K.; Jonsson, J.; Fisker, M. Do no harm and do more good too: Connecting the SDGs with business and human rights and political CSR theory. Corp. Governance: Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2019, 19, 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, R.C. Can Creating Shared Value (CSV) and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs) Collaborate for a Better World? Insights from East Asia. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahdari, A.; Sepasi, S.; Moradi, M. Achieving sustainability through Schumpeterian social entrepreneurship: The role of social enterprises. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 137, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, B.; Miklian, J. Towards global business engagement with development goals? Multilateral institutions and the SDGs in a changing global capitalism. Bus. Politics 2019, 21, 445–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, A.; Costa, R.; Ghiron, N.L.; Menichini, T. Gender Equality Among CSR Managers and its Influence on Sustainable Development: A Comparison Among Italy, Spain and United Kingdom. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 7, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miralles-Quirós, J.L.; Miralles-Quirós, M.D.M.; Nogueira, J.M. Diversification benefits of using exchange-traded funds in compliance to the sustainable development goals. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2018, 28, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gider, D.; Hamm, U. How do consumers search for and process corporate social responsibility information on food companies’ websites? Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2019, 22, 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soonsiripanichkul, B.; Ngamcharoenmongkol, P. The influence of sustainable development goals (SDGs) on customer-based store equity (CBSE). J. Bus. Retail. Manag. Res. 2019, 13, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naciti, V. Corporate governance and board of directors: The effect of a board composition on firm sustainability performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 237, 117727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, M.; Gasparatos, A. Corporate environmental sustainability in the retail sector: Drivers, strategies and performance measurement. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 203, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurunnabi, M.; Esquer, J.; Munguia, N.; Zepeda, D.; Perez, R.; Velazquez, L. Reaching the sustainable development goals 2030: Energy efficiency as an approach to corporate social responsibility (CSR). Geojournal 2019, 85, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, P.; Kar, A.K.; Ilavarasan, P.V. Impact of corporate social responsibility on reputation—Insights from tweets on sustainable development goals by CEOs. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 48, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denoncourt, J. Companies and UN 2030 Sustainable Development Goal 9 Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure. J. Corp. Law Stud. 2019, 20, 199–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, G.K.; Brewster, C.J.; Collings, D.G.; Hajro, A. Enhancing the Role of Human Resource Management in Corporate Sustainability and Social Responsibility: A Multi-Stakeholder, Multidimensional Approach to HRM. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poddar, A.; Narula, S.A.; Zutshi, A. A study of corporate social responsibility practices of the topBombay Stock Exchange500 companies in India and their alignment with theSustainable Development Goals. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 1184–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berning, S.C. The Role of Multinational Enterprises in Achieving Sustainable Development—The Case of Huawei. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 8, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annan-Diab, F.; Molinari, C. Interdisciplinarity: Practical approach to advancing education for sustainability and for the Sustainable Development Goals. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2017, 15, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, R.; Martins, A.; Solnet, D.; Baum, T. Sustaining precarity: Critically examining tourism and employment. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1008–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wofford, D.; Macdonald, S.; Rodehau, C. A call to action on women’s health: Putting corporate CSR standards for workplace health on the global health agenda. Glob. Heal. 2016, 12, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch-Badia, M.-T.; Montllor-Serrats, J.; Tarrazon-Rodon, M.-A. Sustainability and Ethics in the Process of Price Determination in Financial Markets: A Conceptual Analysis. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katamba, D. STRENGTHENING HEALTH CARE SYSTEMS: PRIVATE FOR-PROFIT COMPANIES’ CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY ENGAGEMENTS. J. Compet. Stud. 2017, 25, 40–65. [Google Scholar]

- Fasoulis, I.; Rafet, E.K.; Kurt, R.E. Embracing Sustainability in Shipping: Assessing Industry’s Adaptations Incited by the, Newly, Introduced ‘triple bottom line’ Approach to Sustainable Maritime Development. Soc. Sci. 2019, 8, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantele, S.; Zardini, A. What drives small and medium enterprises towards sustainability? Role of interactions between pressures, barriers, and benefits. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 27, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshehhi, A.; Nobanee, H.; Khare, N. The Impact of Sustainability Practices on Corporate Financial Performance: Literature Trends and Future Research Potential. Sustainability 2018, 10, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Muñoz, R.D.; Medina-Muñoz, D.R. Corporate social responsibility for poverty alleviation: An integrated research framework. Bus. Ethic A Eur. Rev. 2019, 29, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavyalova, E.; Studenikin, N.; Starikova, E. Business participation in implementation of socially oriented sustainable development goals in countries of central asia and the caucasus region. Cent. Asia Caucasus 2018, 19, 56–63. [Google Scholar]

- Mañas-Viniegra, L. Corporate Volunteering within Social Responsibility Strategies of IBEX 35 Companies. RETOS. Revista de Ciencias de la Administración y Economía 2018, 8, 19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, I. Is the Time Right for Human Rights NGOs to Collaborate with Businesses that Want to Stop Dabbling with ‘Corporate Social Responsibility’ and Start Making Social Impact? J. Hum. Rights Pr. 2016, 8, 422–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubilla-Montilla, M.I.; Nieto-Libreros, A.B.; Galindo-Villardón, M.P.; Galindo, M.P.V.; García-Sánchez, I.-M. Are cultural values sufficient to improve stakeholder engagement human and labour rights issues? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 938–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramboarisata, L.; Gendron, C. Beyond moral righteousness: The challenges of non-utilitarian ethics, CSR, and sustainability education. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2019, 17, 100321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, J.C.; Ferreira, T.C.; De Oliveira, M.S.B.; Macini, N.; Caldana, A.C.F. Hidden curriculum in student organizations: Learning, practice, socialization and responsible management in a business school. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2017, 15, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, G.; Bos, J.W.; Kleimeier, S. Self-regulation in sustainable finance: The adoption of the Equator Principles. World Dev. 2019, 122, 306–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, G.; Hooper, N. How David Cooke implemented corporate social responsibility at Konica Minolta Australia. Strat. Leadersh. 2017, 45, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhmann, K.; Jonsson, J.; Fisker, M. Do no harm and do more good too: Connecting the SDGs with business and human rights and political CSR theory. Corp. Governance: Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2019, 19, 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, R.C. Can Creating Shared Value (CSV) and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs) Collaborate for a Better World? Insights from East Asia. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahdari, A.; Sepasi, S.; Moradi, M. Achieving sustainability through Schumpeterian social entrepreneurship: The role of social enterprises. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 137, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, B.; Miklian, J. Towards global business engagement with development goals? Multilateral institutions and the SDGs in a changing global capitalism. Bus. Politics 2019, 21, 445–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, A.; Costa, R.; Ghiron, N.L.; Menichini, T. Gender Equality Among CSR Managers and its Influence on Sustainable Development: A Comparison Among Italy, Spain and United Kingdom. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 7, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miralles-Quirós, J.L.; Miralles-Quirós, M.D.M.; Nogueira, J.M. Diversification benefits of using exchange-traded funds in compliance to the sustainable development goals. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2018, 28, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gider, D.; Hamm, U. How do consumers search for and process corporate social responsibility information on food companies’ websites? Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2019, 22, 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soonsiripanichkul, B.; Ngamcharoenmongkol, P. The influence of sustainable development goals (SDGs) on customer-based store equity (CBSE). J. Bus. Retail. Manag. Res. 2019, 13, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naciti, V. Corporate governance and board of directors: The effect of a board composition on firm sustainability performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 237, 117727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, M.; Gasparatos, A. Corporate environmental sustainability in the retail sector: Drivers, strategies and performance measurement. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 203, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurunnabi, M.; Esquer, J.; Munguia, N.; Zepeda, D.; Perez, R.; Velazquez, L. Reaching the sustainable development goals 2030: Energy efficiency as an approach to corporate social responsibility (CSR). Geojournal 2019, 85, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, P.; Kar, A.K.; Ilavarasan, P.V. Impact of corporate social responsibility on reputation—Insights from tweets on sustainable development goals by CEOs. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 48, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denoncourt, J. Companies and UN 2030 Sustainable Development Goal 9 Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure. J. Corp. Law Stud. 2019, 20, 199–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, G.K.; Brewster, C.J.; Collings, D.G.; Hajro, A. Enhancing the Role of Human Resource Management in Corporate Sustainability and Social Responsibility: A Multi-Stakeholder, Multidimensional Approach to HRM. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poddar, A.; Narula, S.A.; Zutshi, A. A study of corporate social responsibility practices of the topBombay Stock Exchange500 companies in India and their alignment with theSustainable Development Goals. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 1184–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berning, S.C. The Role of Multinational Enterprises in Achieving Sustainable Development—The Case of Huawei. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 8, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annan-Diab, F.; Molinari, C. Interdisciplinarity: Practical approach to advancing education for sustainability and for the Sustainable Development Goals. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2017, 15, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, R.; Martins, A.; Solnet, D.; Baum, T. Sustaining precarity: Critically examining tourism and employment. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1008–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wofford, D.; Macdonald, S.; Rodehau, C. A call to action on women’s health: Putting corporate CSR standards for workplace health on the global health agenda. Glob. Heal. 2016, 12, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch-Badia, M.-T.; Montllor-Serrats, J.; Tarrazon-Rodon, M.-A. Sustainability and Ethics in the Process of Price Determination in Financial Markets: A Conceptual Analysis. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katamba, D. STRENGTHENING HEALTH CARE SYSTEMS: PRIVATE FOR-PROFIT COMPANIES’ CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY ENGAGEMENTS. J. Compet. Stud. 2017, 25, 40–65. [Google Scholar]

- Fasoulis, I.; Rafet, E.K.; Kurt, R.E. Embracing Sustainability in Shipping: Assessing Industry’s Adaptations Incited by the, Newly, Introduced ‘triple bottom line’ Approach to Sustainable Maritime Development. Soc. Sci. 2019, 8, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]