Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Dolores Eliche-Quesada and Version 2 by Vicky Zhou.

Spent oil bleaching earth (SOBE) is a waste product obtained in the refining process of oil. It is estimated that 120 million tons of oil are processed with bleaching earth worldwide, generating 2.5 million tons of spent bleaching earth as residue. Moreover, the serious fire and contamination risks that arise during storage and disposal of spent bleaching earth require appropriate technical solutions. The current treatment of SOBE residue is not in line with the new circular economy policies promoted by the European Union, since in most cases it is disposed of in landfills. New technologies that allow oil recovery and treatment of the earths, aiming to convert them into useful products are then needed.

- spent bleaching earth

- geopolymers

- activating solution

- activator modulus

- compressive strength

- microstructure

1. Introduction

Currently, studies are being carried out for SOBE's possible valorization as an adsorbent in wastewater treatment [1][2][3][4], fertilizer [5] and chicken feeding [6], as well as for its use as a raw material of different construction materials [7][8].

Oil bleaching earths are depleted bentonites, silica and alumina being the major constituents. They consist of 20–40 wt% residual oil, metallic impurities and other organic compounds [9]. Once the oil and organic compounds are removed, due to their composition they can be used as binders in the manufacture of geopolymers.

The manufacture of geopolymers at room temperature using SOBE as a precursor is challenging and constitutes the major novelty of this work. The effect of the modulus of the alkaline activator (mass ratio between sodium silicate and sodium hydroxide Na2SiO3/NaOH solutions) on the geopolymerization reaction was tested. Microstructural development and relevant properties of hardened samples were evaluated and discussed.

2. FacResults about Spent Oil Bleachind Discussiong Earths

2.1. Reaction Degree

The reaction degree of the geopolymers after 28 days curing as a function of the activation solution modulus, Na2SiO3/NaOH mass ratio, is presented in Table 13. HCl extraction dissolves sodium aluminosilicate, calcium aluminosilicate and carbonate phases [10]. The reaction degree tends to increase in samples prepared with higher Na2SiO3/NaOH mass ratios, indicating the formation of a greater amount of N-A-S-H geopolymer gel.

Table 13. Reaction degree of the samples.

| Sample | G-SOBE-1:1 | G-SOBE-1:2 | G-SOBE-1:3 | G-SOBE-1:4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reaction degree (%) | 52.5 | 47.3 | 45.7 | 43.5 |

2.2. Mineralogy of Geopolymer Binders

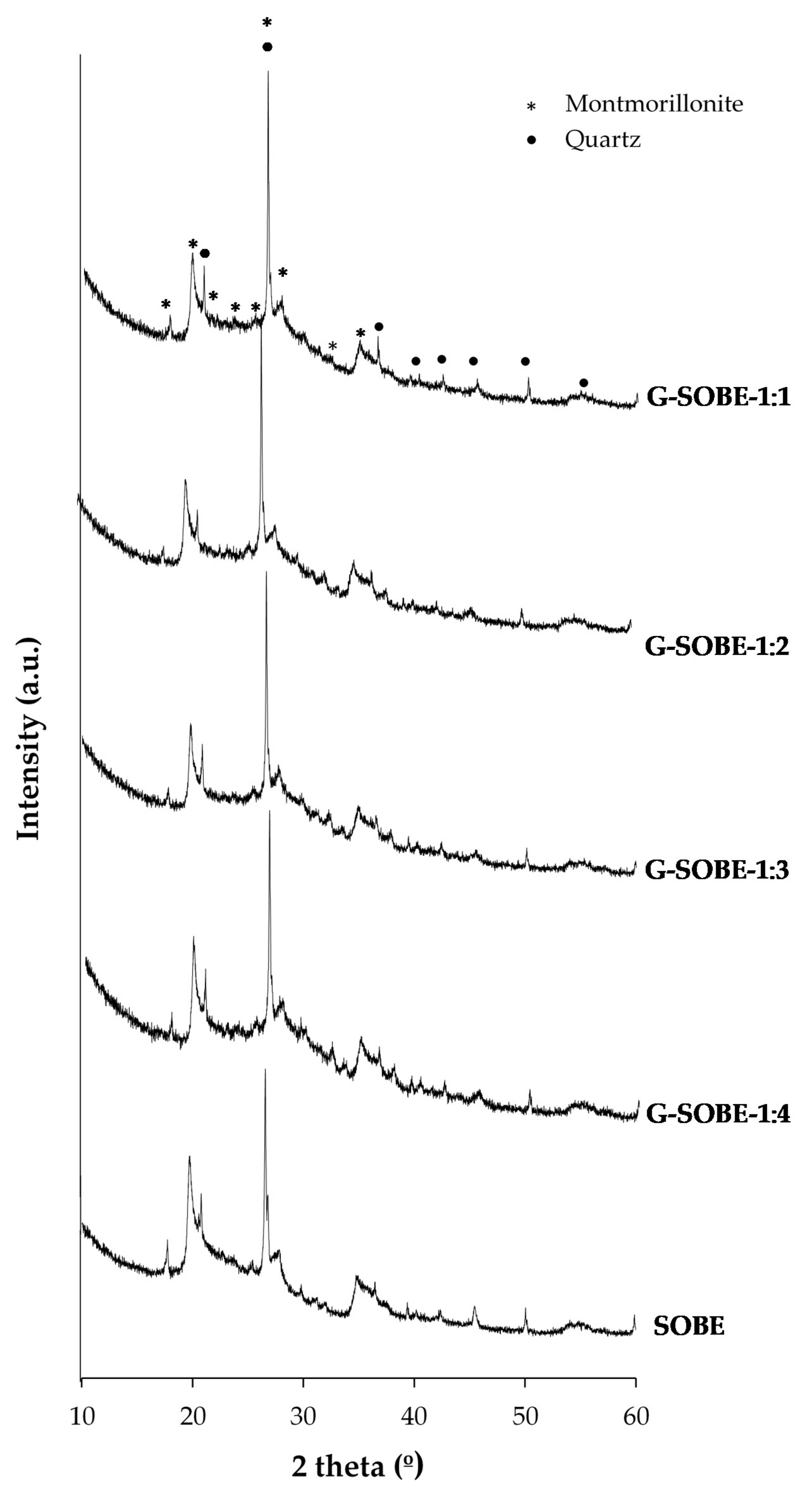

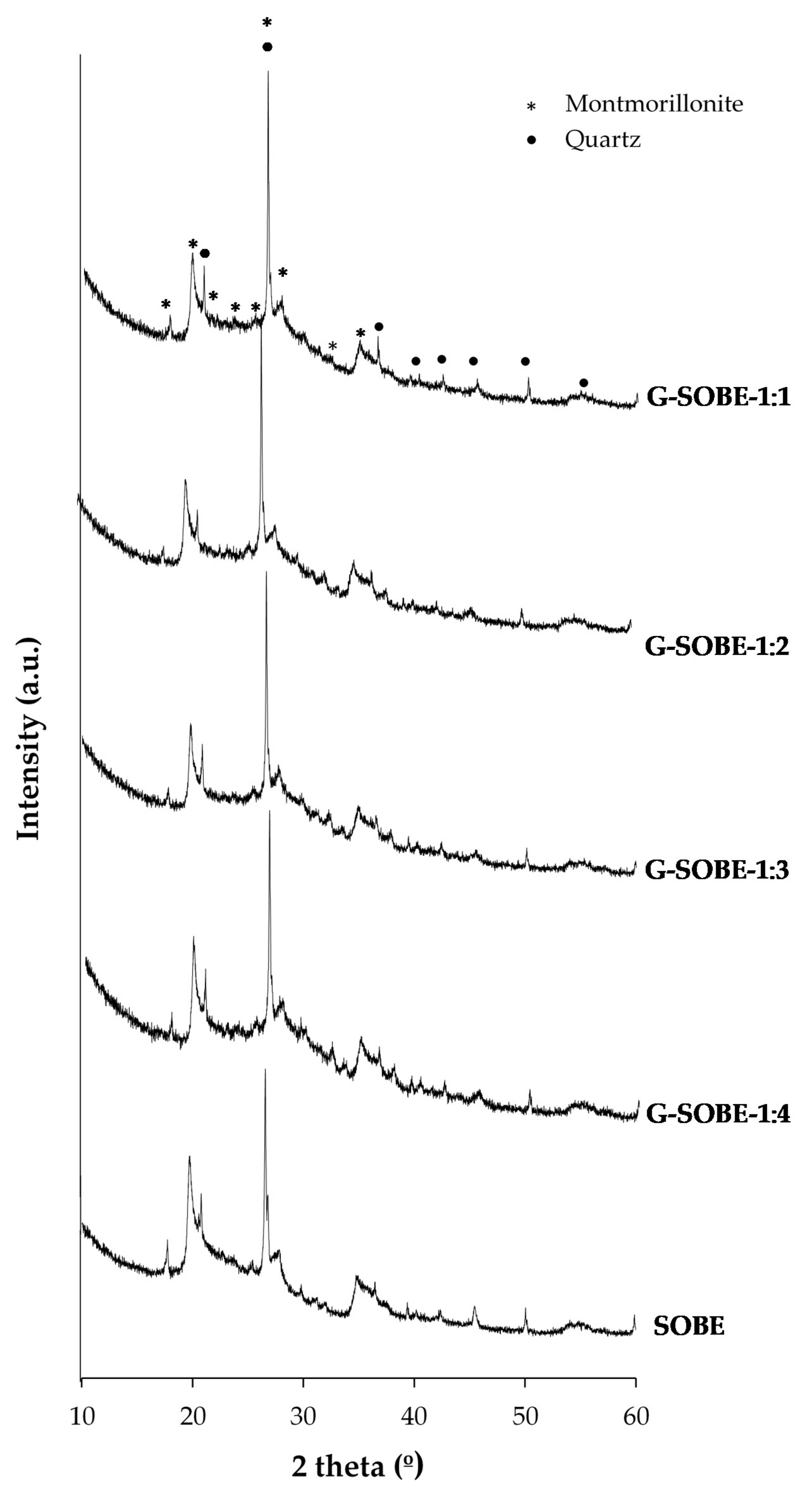

Figure 25 shows XRD spectra of the precursor and geopolymer binders. Patterns are similar, being montmorillonite and quartz, the crystalline phases having been detected. The partial dissolution of montmorillonite upon geopolymerization, revealed by the FTIR analyses and confirmed by QPA results (Table 24) [11], and the increase in the amorphous phase are the most relevant observations. However, the fraction of montmorillonite that dissolves is small for all the activator modules used, as observed by other authors [12]. Quartz peaks remain almost unchanged, indicating its non-reactive character. The analysis confirms the low dissolution of the crystalline phases by the activating solutions. The amorphous hump at 18–30° (2θ) in the SOBE precursor becomes more prominent and slightly shifts to 20–35° (2θ) with the geopolymerization progress [13].

Figure 25. XRD of raw material and geopolymer cements as function of Na2SiO2/NaOH mass ratio of activating solution.

Figure 25. XRD of raw material and geopolymer cements as function of Na2SiO2/NaOH mass ratio of activating solution.

Figure 25. XRD of raw material and geopolymer cements as function of Na2SiO2/NaOH mass ratio of activating solution.

Figure 25. XRD of raw material and geopolymer cements as function of Na2SiO2/NaOH mass ratio of activating solution.Table 24. Quantitative crystalline phase composition as derived from the Rietveld refinements *.

| Phase Composition (wt%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Sample | Montmorillonite | α-Quartz |

| Raw material | 82.4 ± 0.2 | 17.6 ± 0.3 |

| G-SOBE-1:1 | 81.8 ± 0.2 | 18.2 ± 0.2 |

| G-SOBE-1:2 | 81.3 ± 0.2 | 18.7 ± 0.3 |

| G-SOBE-1:3 | 81.7 ± 0.2 | 18.3 ± 0.5 |

| G-SOBE-1:4 | 80.5 ± 0.2 | 19.5 ± 0.3 |

2.3. Bulk Density, Total Porosity and Water Absorption of Geopolymer Binders

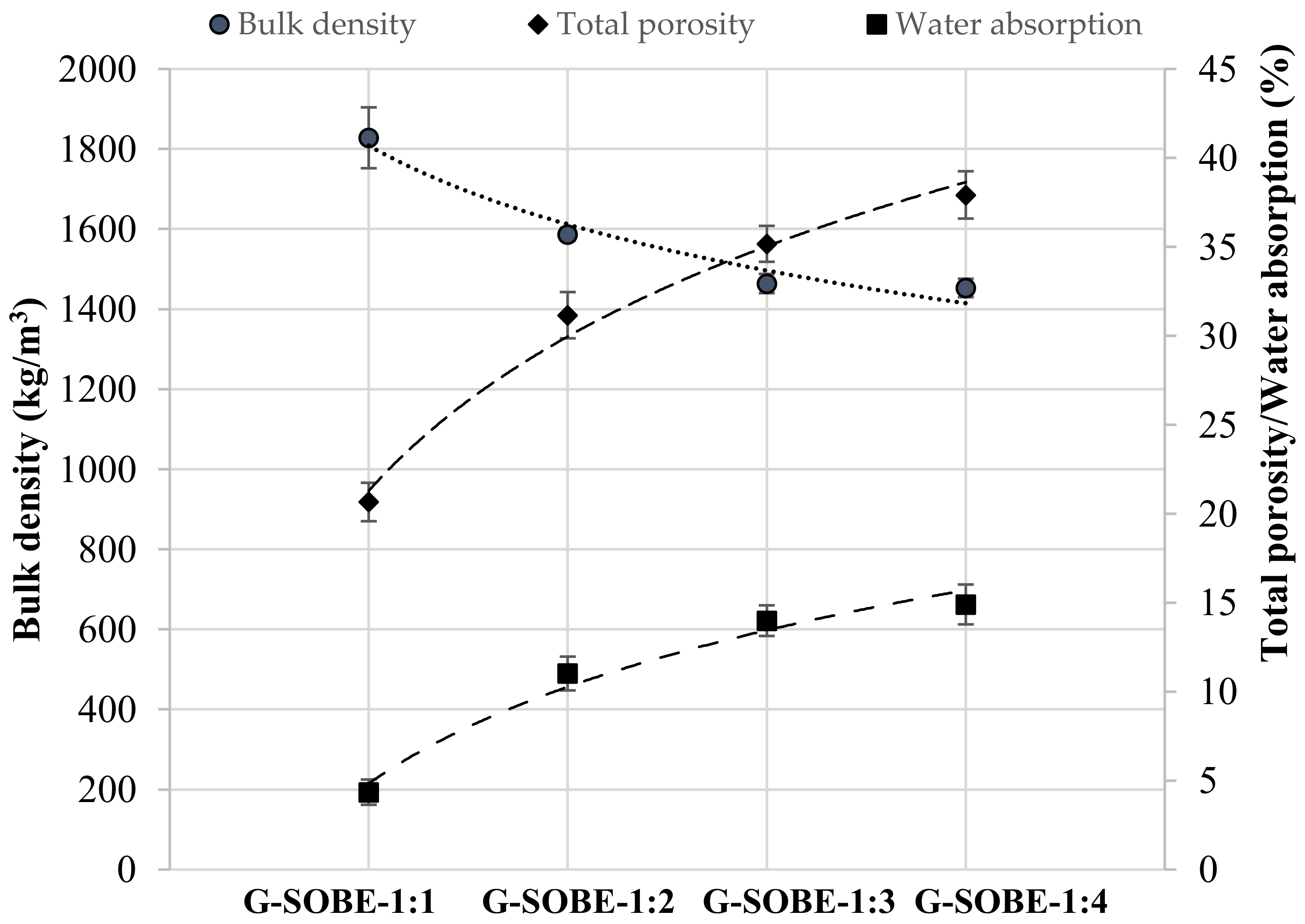

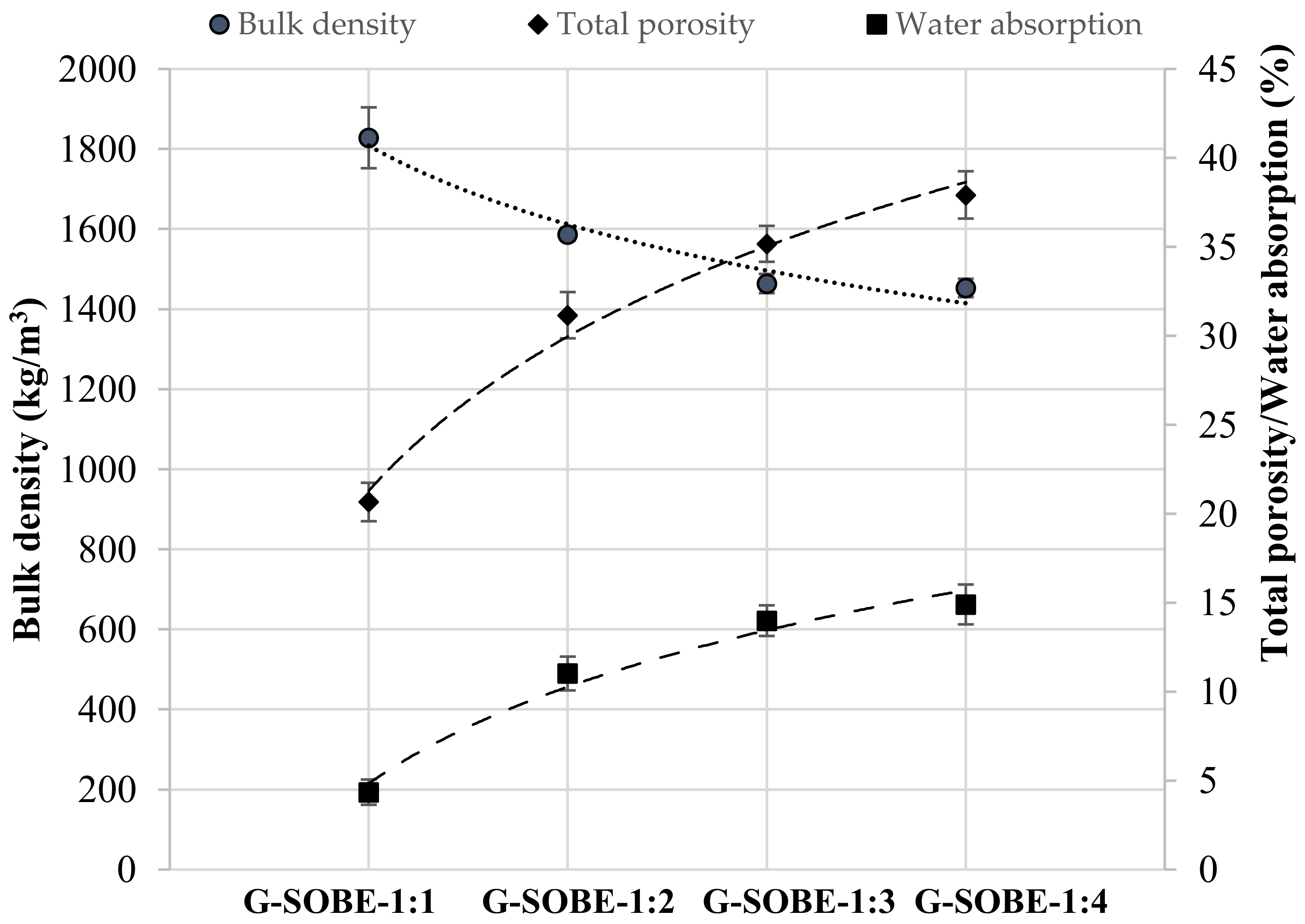

The values of bulk density, total porosity and water absorption of the geopolymers are shown in Figure 36. As expected, bulk density and total porosity or water absorption values followed an opposite tendency when the Na2SiO3/NaOH mass ratio of the activator changed. G-SOBE-1:1 specimens have a bulk density of 1828 kg/m3, total porosity of 20.7% and water absorption of 4.35%. As the Na2SiO3/NaOH mass ratio decreases, density decreases while total porosity and water absorption increases: G-SOBE-1:4 geopolymers show density = 1453 kg/m3, total porosity = 37.9% and water absorption = 14.9%. Samples prepared with lower Na2SiO3/NaOH mass ratios have more water (see Table 2). The water/binder ratio increases from 0.71 in G-SOBE-1:1 to 0.81 in G-SOBE-1:4 specimens; the removal of water will generate porosity [14]. Inadequate amounts of binder precursor and alkali solution results in less efficient dissolution of the precursor, with consequent creation of pores in the geopolymer matrix and the formation of a less homogeneous structure [15]. The ultimate removal of excess water upon drying will also create porosity. A decrease in the Si/Al molar ratio tends to generate less dense structures as a consequence of slower geopolymerization, according to the degree of reaction data [16]. So, we have physical and chemical/reactive contributions to the observed tendencies.

Figure 36. Bulk density, total porosity and water absorption of geopolymers after 28 days of curing as functions of the Na2SiO3/NaOH mass ratio.

Figure 36. Bulk density, total porosity and water absorption of geopolymers after 28 days of curing as functions of the Na2SiO3/NaOH mass ratio.

Figure 36. Bulk density, total porosity and water absorption of geopolymers after 28 days of curing as functions of the Na2SiO3/NaOH mass ratio.

Figure 36. Bulk density, total porosity and water absorption of geopolymers after 28 days of curing as functions of the Na2SiO3/NaOH mass ratio.2.4. Compressive and Flexural Strength of Geopolymer Binders

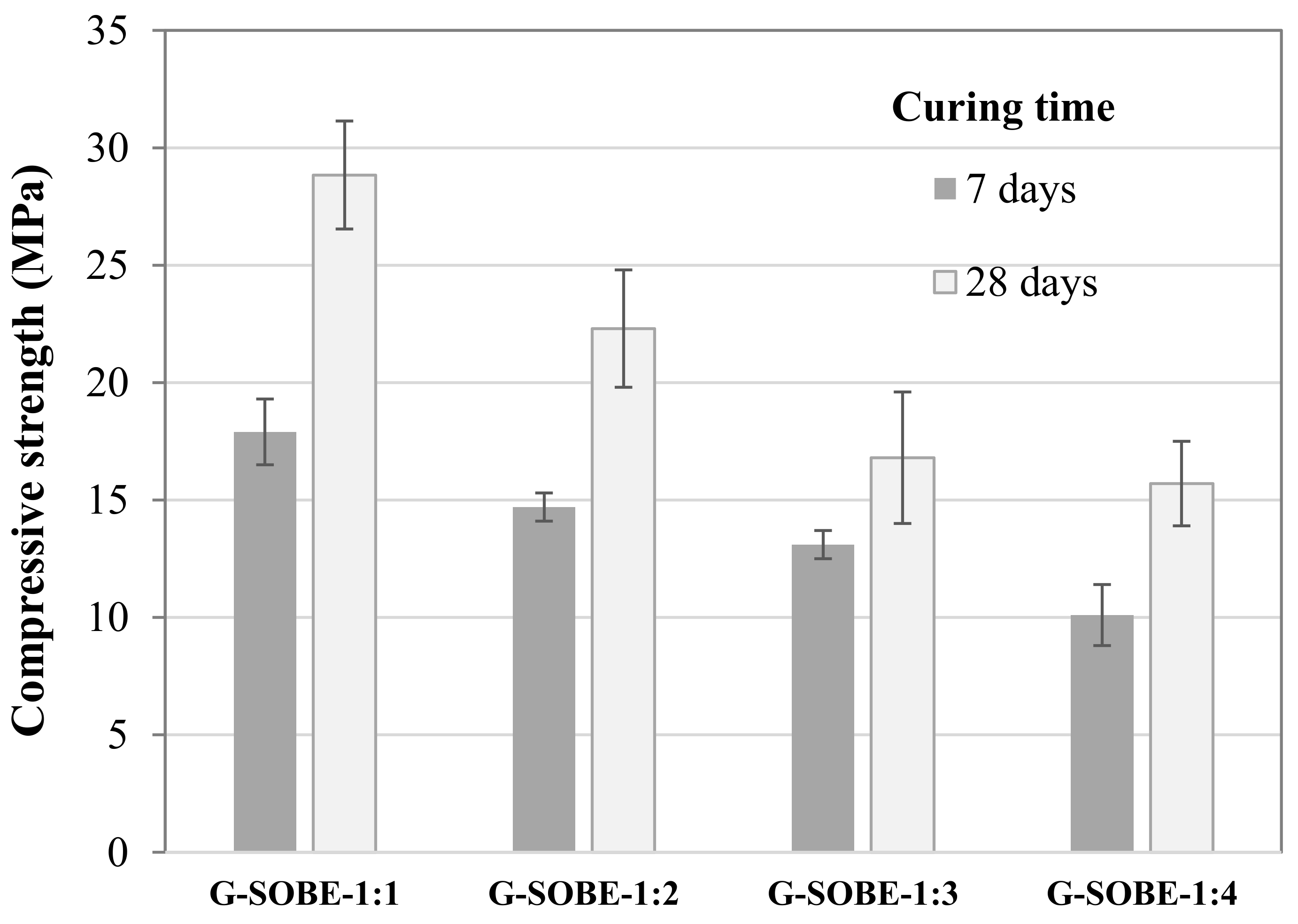

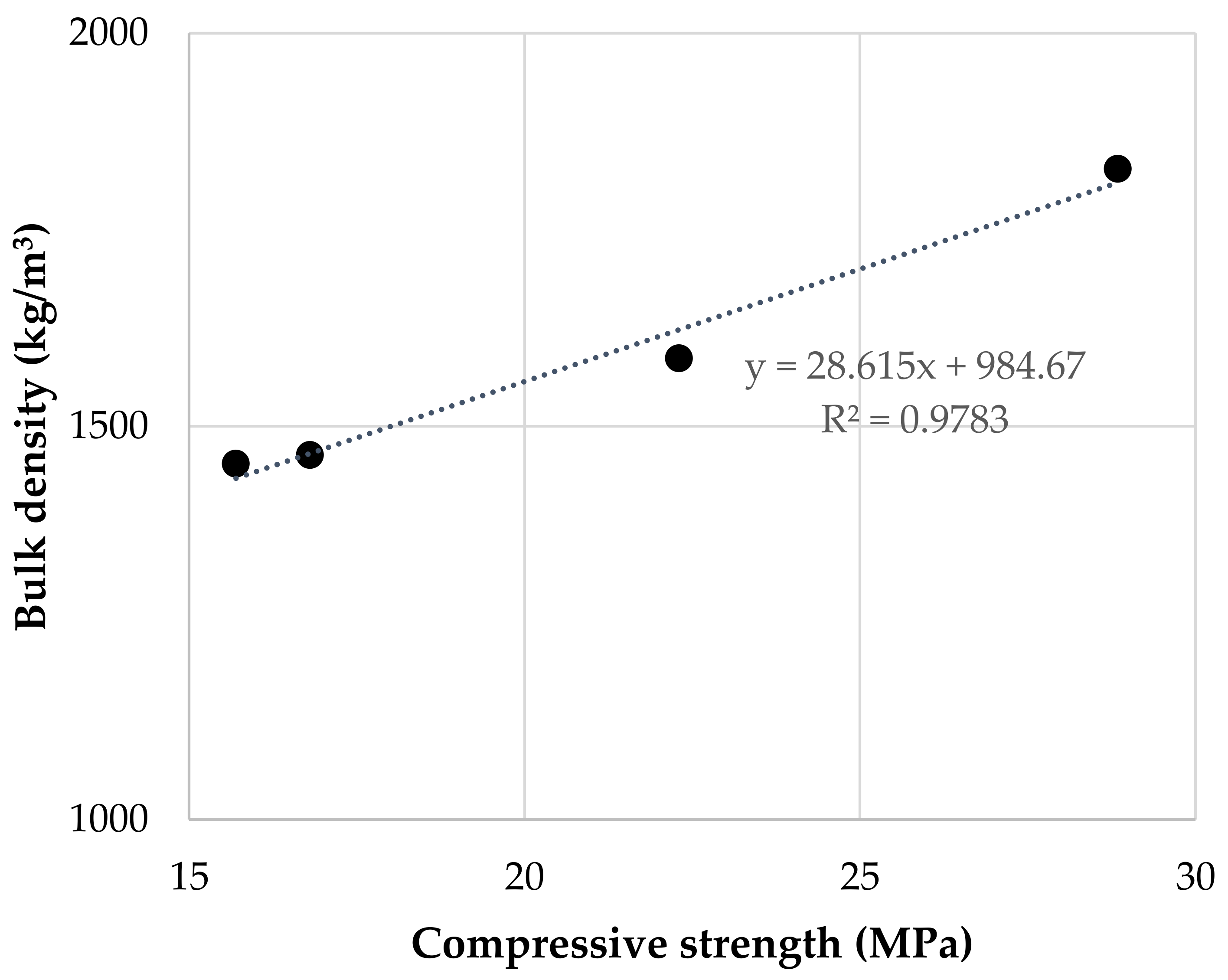

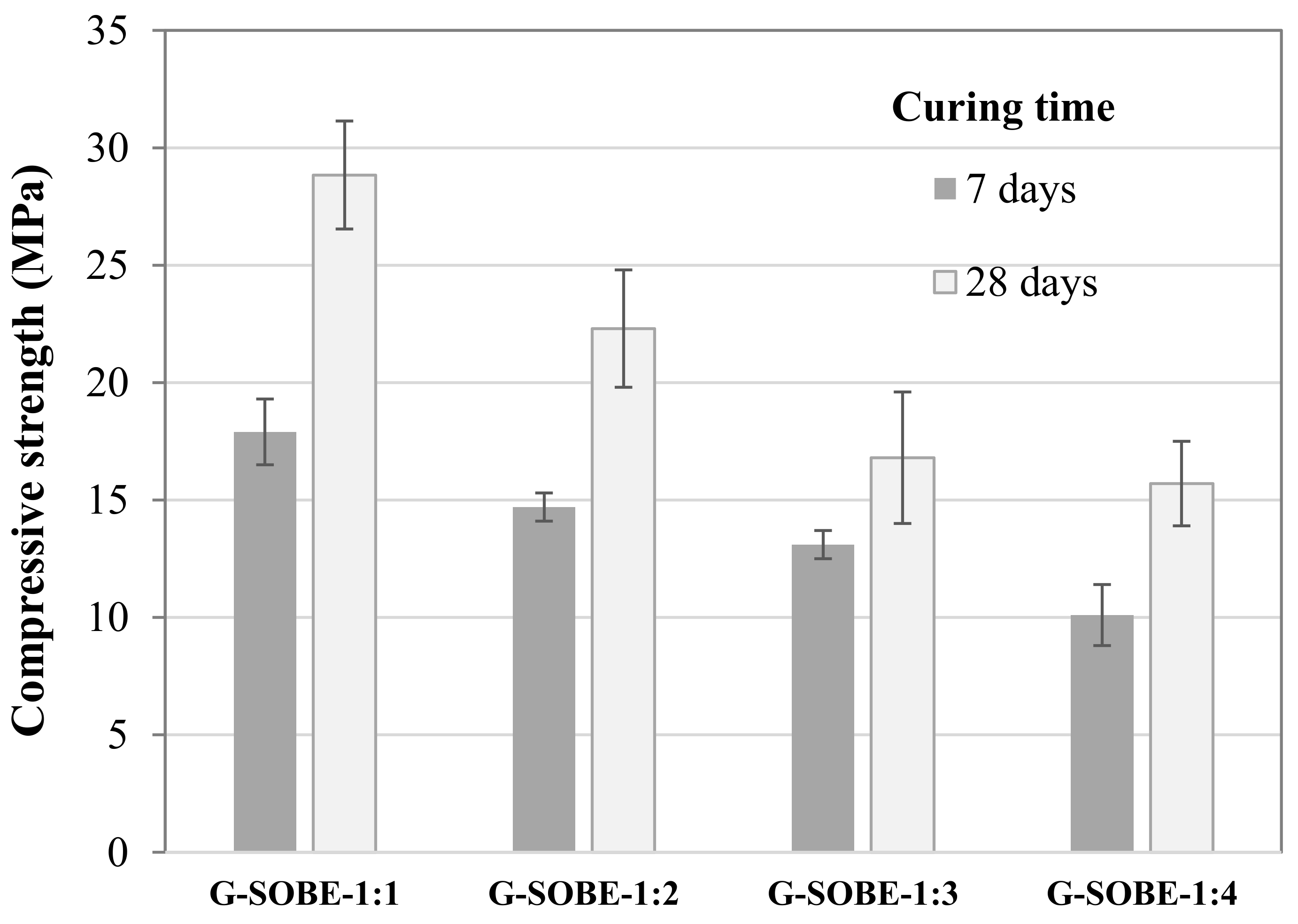

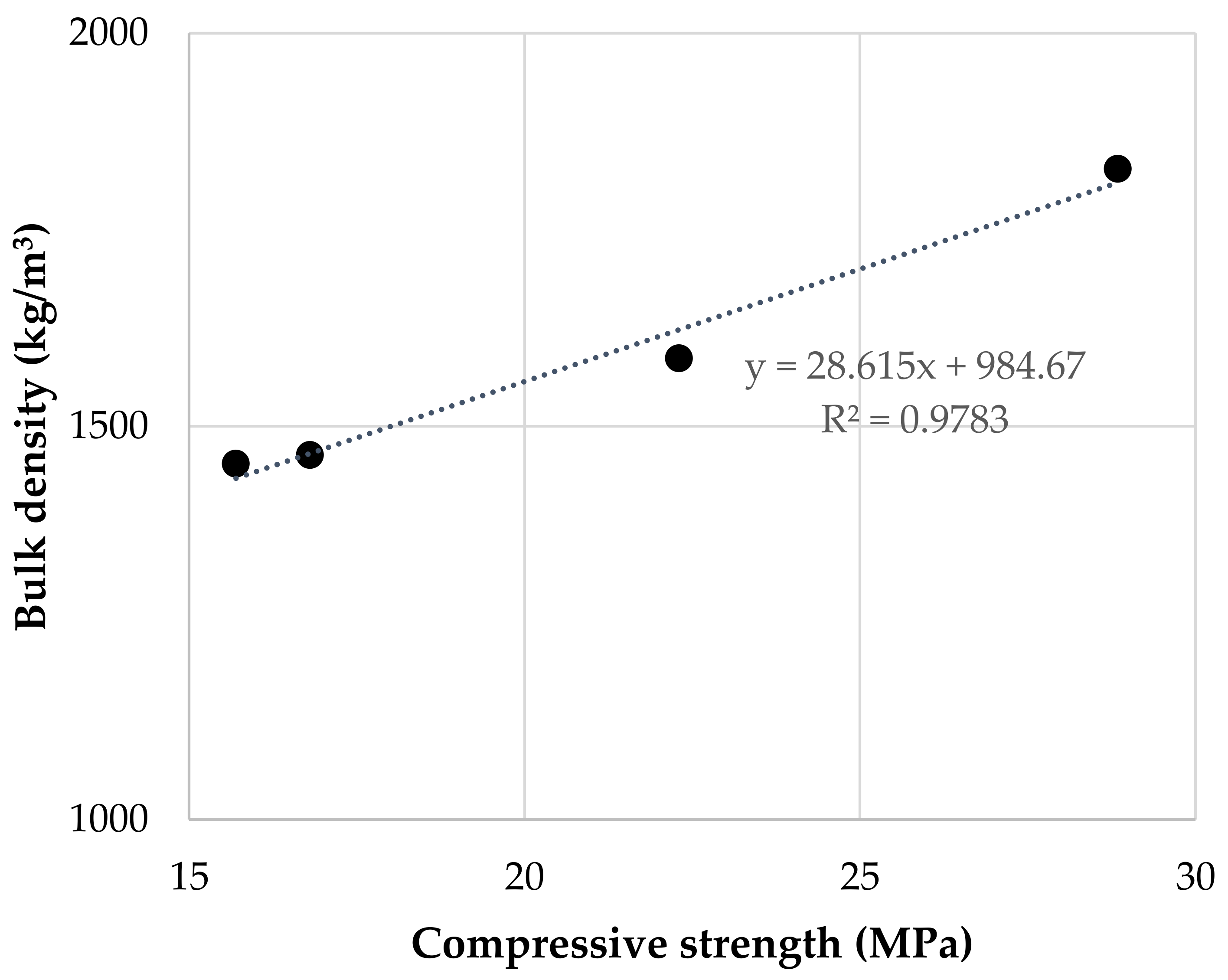

Figure 37 shows the compressive strength of samples cured for 7 and 28 days. Values ranged from 10.1 to 17.9 MPa (7 days) and 15.7 to 28.9 MPa (28 days). An increase in the Na2SiO3/NaOH mass ratio enhances resistance, in direct relationship with higher compactness. Figure 48 shows a linear correlation between compressive strength and bulk density. The enhancement of soluble Si, by using an activator with a higher modulus, extends the geopolymerization process and the formation of the N-A-S-H aluminosilicate gel responsible for the consolidation of the geopolymer matrix and the development of mechanical strength [17][18][19][20][21].

Figure 37. Compressive strength of samples cured for 7 and 28 days.

Figure 37. Compressive strength of samples cured for 7 and 28 days.

Figure 48. Relationship between bulk density and compressive strength of geopolymers cured for 28 days.

Figure 48. Relationship between bulk density and compressive strength of geopolymers cured for 28 days.

Figure 37. Compressive strength of samples cured for 7 and 28 days.

Figure 37. Compressive strength of samples cured for 7 and 28 days. Figure 48. Relationship between bulk density and compressive strength of geopolymers cured for 28 days.

Figure 48. Relationship between bulk density and compressive strength of geopolymers cured for 28 days.

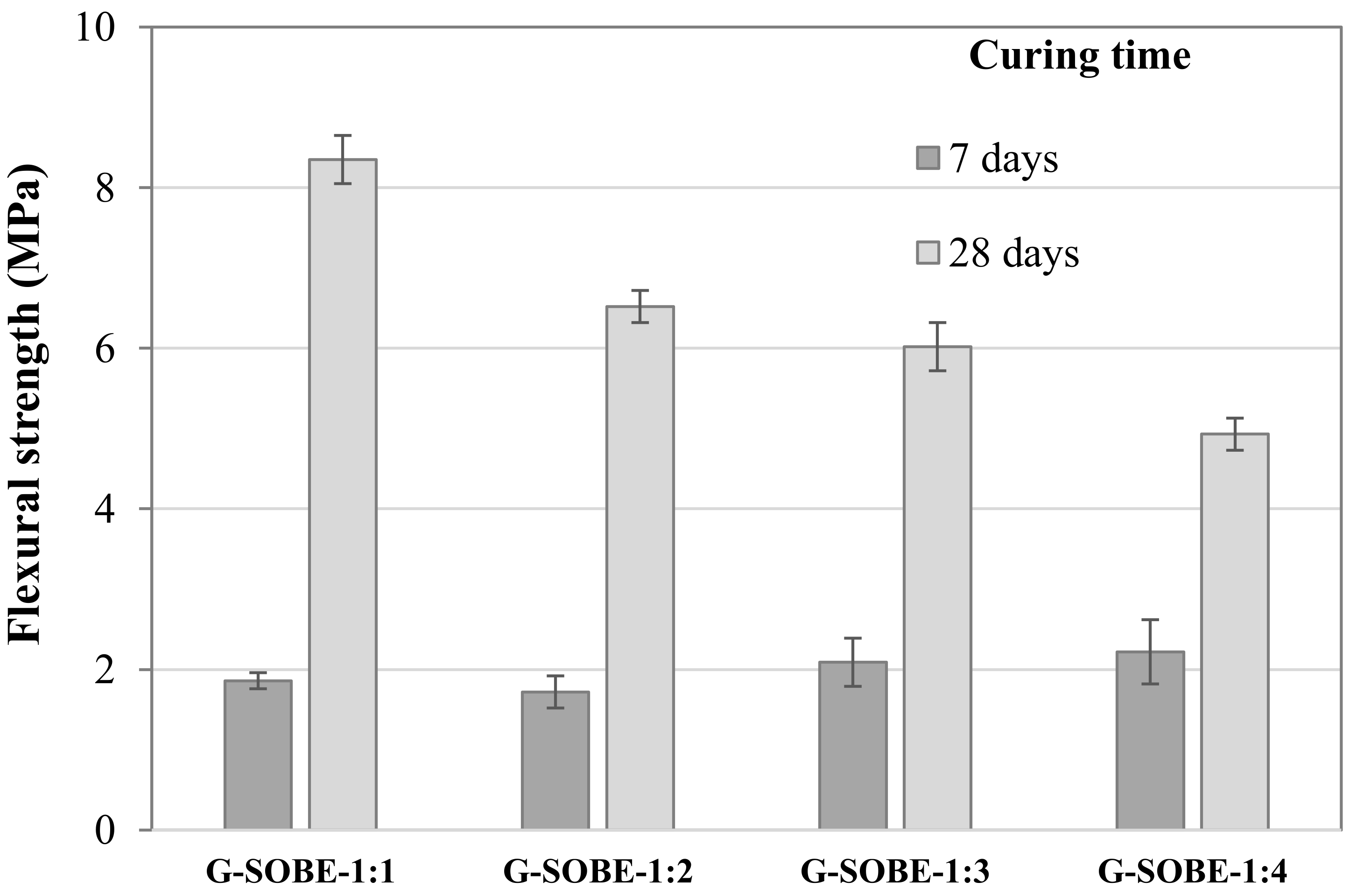

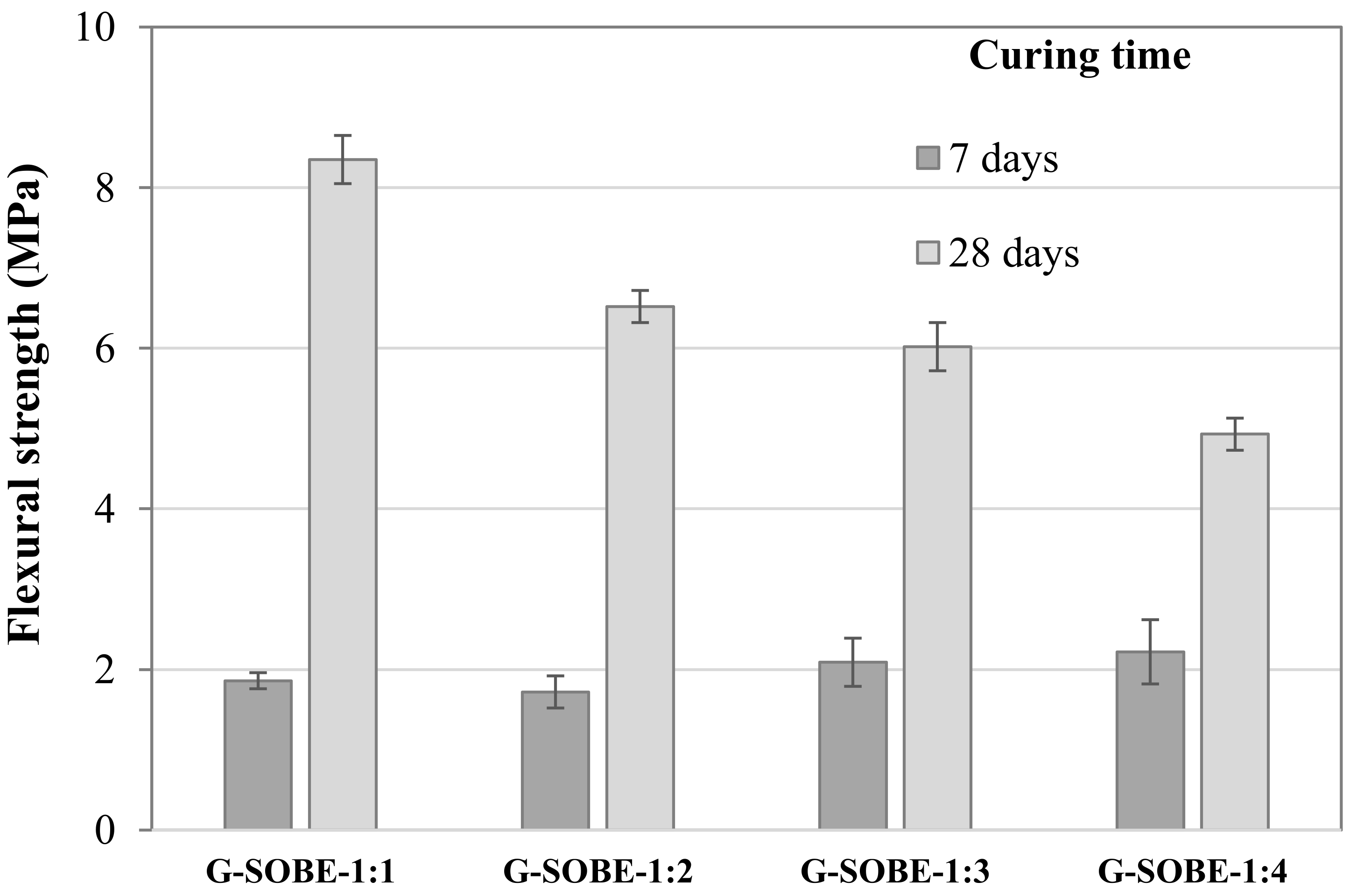

The flexural strength values of the samples are shown in Figure 59. Between distinct formulations the changes follow the same trend in mechanical resistance after 28 days curing. However, differences after 7 days are minor, and sample G-SOBE-1:4 shows the maximum value (2.2 MPa). Progress with curing age is now more expressive, and resistance after 28 curing days is three to four times higher than at 7 days. Interestingly, it was observed that flexural strength values are only about three times lower than corresponding compressive resistances in samples cured for 28 days.

Figure 59. Flexural strength of samples cured for 7 and 28 days.

Figure 59. Flexural strength of samples cured for 7 and 28 days.

Figure 59. Flexural strength of samples cured for 7 and 28 days.

Figure 59. Flexural strength of samples cured for 7 and 28 days.2.5. Thermal Conductivity

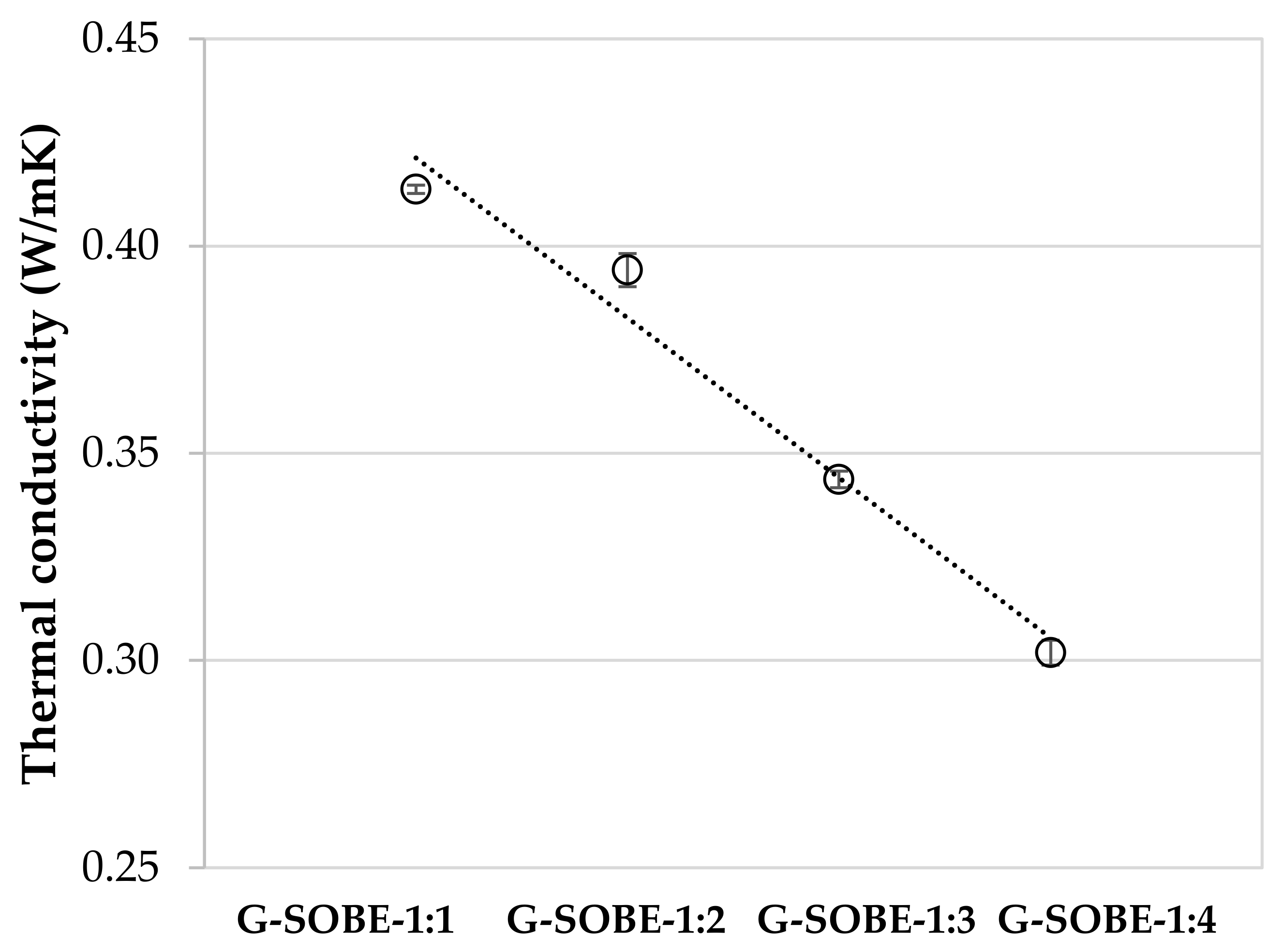

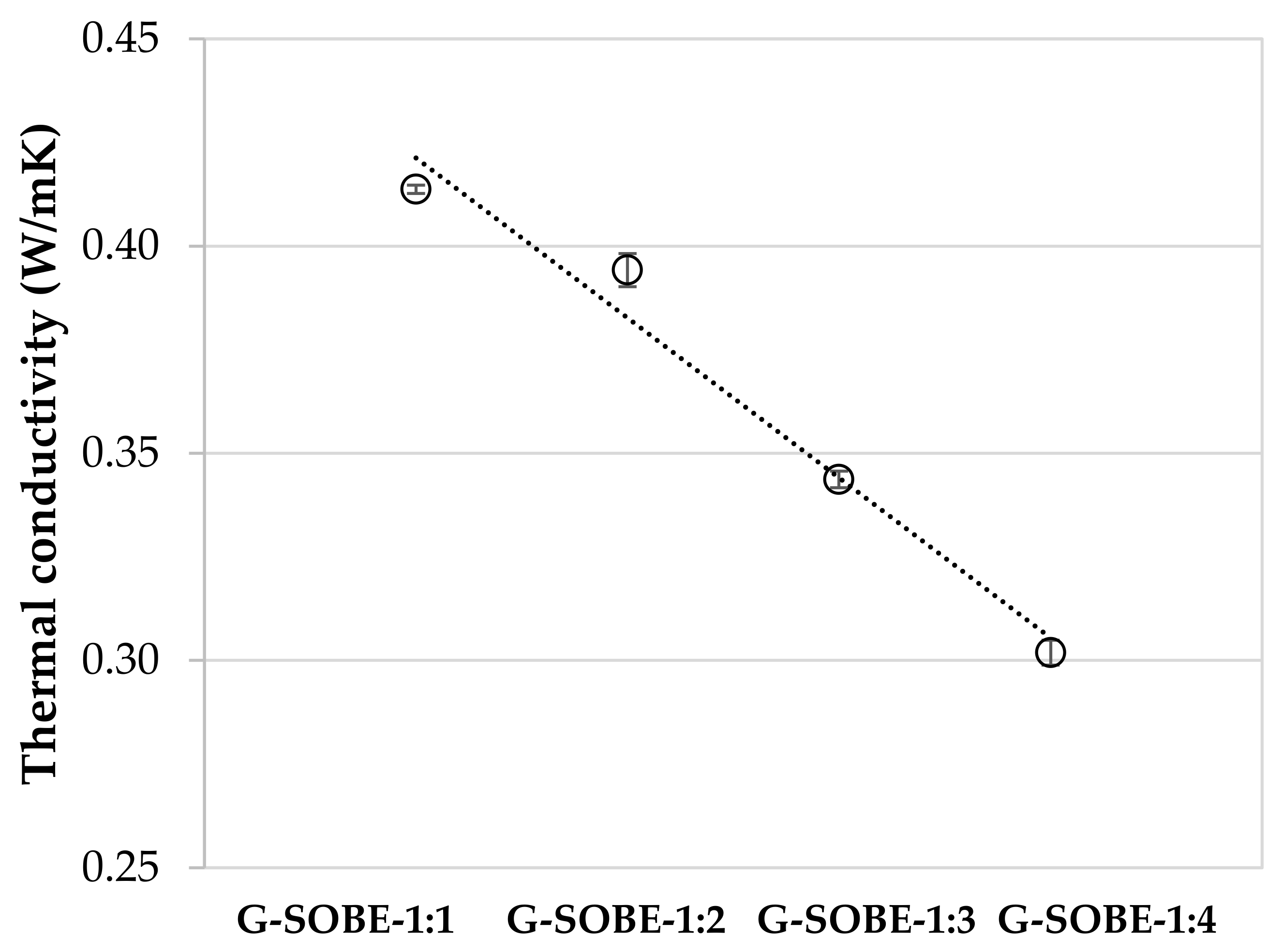

The geopolymers showed thermal conductivity values in the range 0.30–0.41 W/mK (Figure 610), being lower in samples less dense (the ones prepared with a lower Na2SiO3/NaOH mass ratio). As expected, there is an inverse relationship between thermal conductivity and porosity [22]. In general, geopolymers exhibit lower thermal conductivity values than Portland cement (1.5 W/mK) [23][24], due to the existence of pores in the microstructure [25][26].

Figure 610. Thermal conductivity of samples cured for 28 days.

Figure 610. Thermal conductivity of samples cured for 28 days.

Figure 610. Thermal conductivity of samples cured for 28 days.

Figure 610. Thermal conductivity of samples cured for 28 days.2.6. Microstructure of Geopolymer Binders

SEM micrographs at different magnifications of geopolymer binders cured for 28 days are shown in Figure 711 and Figure 812. At low magnification (220×, Figure 711) a homogeneous, dense and compact morphology can be observed in all samples. In any case, non-homogeneously distributed pores and some microcracks are visible. As expected from the density/porosity values, G-SOBE-1:1 samples seem more compact.

Figure 711. SEM micrographs (220× magnification) of geopolymers cured for 28 days. (a) G-SOBE-1:1; (b) G-SOBE-1:2; (c) G-SOBE-1:3; and (d) G-SOBE-1:4.

Figure 711. SEM micrographs (220× magnification) of geopolymers cured for 28 days. (a) G-SOBE-1:1; (b) G-SOBE-1:2; (c) G-SOBE-1:3; and (d) G-SOBE-1:4.

Figure 812. SEM/EDS micrographs (2000× magnification) of geopolymers cured for 28 days. (a) G-SOBE-1:1; (b) G-SOBE-1:2; (c) G-SOBE-1:3; and (d) G-SOBE-1:4.

Figure 812. SEM/EDS micrographs (2000× magnification) of geopolymers cured for 28 days. (a) G-SOBE-1:1; (b) G-SOBE-1:2; (c) G-SOBE-1:3; and (d) G-SOBE-1:4.

Figure 711. SEM micrographs (220× magnification) of geopolymers cured for 28 days. (a) G-SOBE-1:1; (b) G-SOBE-1:2; (c) G-SOBE-1:3; and (d) G-SOBE-1:4.

Figure 711. SEM micrographs (220× magnification) of geopolymers cured for 28 days. (a) G-SOBE-1:1; (b) G-SOBE-1:2; (c) G-SOBE-1:3; and (d) G-SOBE-1:4. Figure 812. SEM/EDS micrographs (2000× magnification) of geopolymers cured for 28 days. (a) G-SOBE-1:1; (b) G-SOBE-1:2; (c) G-SOBE-1:3; and (d) G-SOBE-1:4.

Figure 812. SEM/EDS micrographs (2000× magnification) of geopolymers cured for 28 days. (a) G-SOBE-1:1; (b) G-SOBE-1:2; (c) G-SOBE-1:3; and (d) G-SOBE-1:4.

As the Na2SiO3/NaOH mass ratio decreases, more pores formed due to water evaporation during curing [27] are observed, possibly due to an increase in the water/binder ratio (Table 2).

At higher magnification (2000×, Figure 812), sodium aluminosilicate gel with a spongy and globular morphology is visible in all samples. Its elemental chemical composition reveals the dominance of silicon, aluminum and sodium (zone 1 EDS analysis), as expected. In addition, unreacted SOBE particles with angular shapes are also visible. EDS analysis (zone 2) shows an abundance of silicon and aluminum, and smaller quantities of potassium, iron and magnesium. It can be observed that as the amount of sodium silicate decreases the geopolymers contain more unreacted SOBE particles and possess a higher porosity.

3. Conclusions

Spent oil bleaching earths (SOBE), generated in the oil bleaching process, were used as a precursor of geopolymer binders prepared with activating solutions with distinct Na2SiO3/NaOH mass ratios. Physical, mechanical and thermal properties changed with the mentioned activator modulus. Flexural and compressive strengths, bulk density and thermal conductivity increase when the Na2SiO3/NaOH mass ratio increases, while total porosity and water absorption decrease. Maximal flexural (8.4 MPa) and compressive (28.8 MPa) strength values were obtained in samples cured for 28 days at room temperature. The enrichment of soluble Si with the use of a higher amount of sodium silicate in the activator enhances the geopolymerization rate and extends it, generating higher compact and homogeneous microstructures due to the formation of a higher amount of three-dimensional aluminosilicate hydrate [N-A-S-H] gel.References

- Tang, J.; Mu, B.; Zheng, M.; Wang, A. One-Step Calcination of the Spent Bleaching Earth for the Efficient Removal of Heavy Metal Ions. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2015, 3, 1125–1135.

- Tang, J.; Mu, B.; Wang, W.; Zheng, M.; Wang, A. Fabrication of manganese dioxide/carbon/attapulgite composites derived from spent bleaching earth for adsorption of Pb(ii) and Brilliant green. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 36534–36543.

- Tang, J.; Mu, B.; Zong, L.; Zheng, M.; Wang, A. Facile and green fabrication of magnetically recyclable carboxyl-functionalized attapulgite/carbon nanocomposites derived from spent bleaching earth for wastewater treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 322, 102–114.

- Mana, M.; Ouali, M.S.; Lindheimer, M.; de Menorval, L.C. Removal of lead from aqueous solutions with a treated spent bleaching earth. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 159, 358–364.

- Kheang Loh, S.; James, S.; Ngatiman, M.; Yein Cheong, K.; May Choo, Y.; Soon Lim, W. Enhancement of palm oil refinery waste—Spent bleaching earth (SBE) into bio organic fertilizer and their effects on crop biomass growth. Ind. Crops Prod. 2013, 49, 775–781.

- Dijkstra, A.J. What to Do with Spent Bleaching Earth? A Review. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2020, 97, 565–575.

- Srisang, S.; Srisang, N. Recycling spent bleaching earth and oil palm ash to tile production: Impact on properties, utilization, and microstructure. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 294, 126336.

- Eliche-Quesada, D.; Iglesias, F.A.C. Utilisation of spent filtration earth or spent bleaching earth from the oil refinery industry in clay products. Ceram. Int. 2014, 40, 16677–16687.

- Boey, P.-L.; Ganesan, S.; Maniam, G.P.; Ali, D.M.H. Ultrasound aided in situ transesterification of crude palm oil adsorbed on spent bleaching clay. Energy Convers. Manag. 2011, 52, 2081–2084.

- García-Lodeiro, I.; Fernández-Jiménez, A.; Blanco, M.T.; Palomo, A. FTIR study of the sol-gel synthesis of cementitious gels: C-S-H and N-A-S-H. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2008, 45, 63–72.

- Zhang, G.; Ke, Y.; He, J.; Qin, M.; Shen, H.; Lu, S.; Xu, J. Effects of organo-modified montmorillonite on the tribology performance of bismaleimide-based nanocomposites. Mater. Des. 2015, 86, 138–145.

- Anh, H.N.; Ahn, H.; Jo, H.Y.; Kim, G.-Y. Effect of alkaline solutions on bentonite properties. Environ. Earth Sci. 2017, 76, 374.

- Provis, J.L.; Lukey, A.G.C.; Van Deventer, J.S.J. Do Geopolymers Actually Contain Nanocrystalline Zeolites? A Reexamination of Existing Results. Chem. Mater. 2005, 17, 3075–3085.

- Leong, H.Y.; Ong, D.E.L.; Sanjayan, J.G.; Nazari, A. The effect of different Na2O and K2O ratios of alkali activator on compressive strength of fly ash based-geopolymer. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 106, 500–511.

- Ibrahim, M.; Johari, M.A.M.; Rahman, M.K.; Maslehuddin, M. Effect of alkaline activators and binder content on the properties of natural pozzolan-based alkali activated concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 147, 648–660.

- Toniolo, N.; Rincon, A.; Roether, J.; Ercole, P.; Bernardo, E.; Boccaccini, A. Extensive reuse of soda-lime waste glass in fly ash-based geopolymers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 188, 1077–1084.

- Hanjitsuwan, S.; Hunpratub, S.; Thongbai, P.; Maensiri, S.; Sata, V.; Chindaprasirt, P. Effects of NaOH concentrations on physical and electrical properties of high calcium fly ash geopolymer paste. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2014, 45, 9–14.

- Glid, M.; Sobrados, I.; Ben Rhaiem, H.; Sanz, J.; Amara, A.B.H. Alkaline activation of metakaolinite-silica mixtures: Role of dissolved silica concentration on the formation of geopolymers. Ceram. Int. 2017, 43, 12641–12650.

- Hameed, A.M.; Rawdhan, R.R.; Al-Mishhadani, S.A. Effect of various factors on the manufacturing of geopolymer mortar. Arch. Sci. 2017, 1, 111.

- Xu, H.; Van Deventer, J.S.J. The geopolymerisation of alumino-silicate minerals. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2000, 59, 247–266.

- Hardjito, D.; Wallah, S.E.; Sumajouw, D.M.J.; Rangan, B.V. Fly Ash-Based Geopolymer Concrete. Aust. J. Struct. Eng. 2005, 6, 77–86.

- Huiskes, D.; Keulen, A.; Yu, Q.; Brouwers, H. Design and performance evaluation of ultra-lightweight geopolymer concrete. Mater. Des. 2016, 89, 516–526.

- Yun, T.S.; Jeong, Y.J.; Han, T.-S.; Youm, K.-S. Evaluation of thermal conductivity for thermally insulated concretes. Energy Build. 2013, 61, 125–132.

- Pan, Z.; Feng, K.N.; Gong, K.; Zou, B.; Korayem, A.H.; Sanjayan, J.; Duan, W.H.; Collins, F. Damping and microstructure of fly ash-based geopolymers. J. Mater. Sci. 2012, 48, 3128–3137.

- Albitar, M.; Ali, M.M.; Visintin, P.; Drechsler, M. Durability evaluation of geopolymer and conventional concretes. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 136, 374–385.

- Zhang, Z.; Provis, J.L.; Reid, A.; Wang, H. Mechanical, thermal insulation, thermal resistance and acoustic absorption properties of geopolymer foam concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2015, 62, 97–105.

- Rashad, A.M.; Sadek, D.M.; Hassan, H.A. An investigation on blast-furnace stag as fine aggregate in alkali-activated slag mortars subjected to elevated temperatures. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 1086–1096.

More